Arguing about Iran's nuke programme

The argument about Iran's right to a nuclear programme rumbles on at indymedia, while a new poll conducted independently of the government in Tehran finds that 85% of Iranians give the programme the thumbs up.

Kiwi kulcha. Cartography. History. Herstory. Dams. Ordinary Days Beyond Kaitaia. Coal. Rotowaro. Rodney Redmond. Poetics. Musket pa. Five wicket bags. Limestone Country. Allen Curnow. Owen Gager. Huntly. Kahikatea. Te Kooti. The Clean. Base and superstructure. Earthquake Weather. Dune lakes. Epistemology. Middens. Marx. Te Aroha. Time Travel. Te Kopuru. SO DRIVE SLOWLY. YOU'LL NEED TO. THE MAP SAYS THE ROAD ENDS THERE. NOT TRUE.

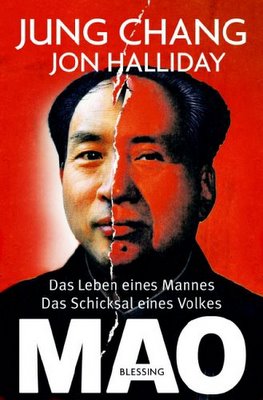

Mao is the latest 'dead male' to get a going-over at indymedia, courtesy of Dean Parker's curious mixture of anecdote and lofty condesencion. The Chang-Halliday biography Parker reviewed for The Listener enjoyed a blaze of publicity in the media immediately after its publication, but has since attracted the ire of a number of academic comentators. Of course, the pointy-heads take longer to chew over the evidence than the feature writers of the mass media, and their verdicts tend to be more cautious, and less easily coralled by sub-editors into sensational headlines. It'll be no surprise, then, if the more extraordinary claims of Chang and Halliday stick in the public mind.

Mao is the latest 'dead male' to get a going-over at indymedia, courtesy of Dean Parker's curious mixture of anecdote and lofty condesencion. The Chang-Halliday biography Parker reviewed for The Listener enjoyed a blaze of publicity in the media immediately after its publication, but has since attracted the ire of a number of academic comentators. Of course, the pointy-heads take longer to chew over the evidence than the feature writers of the mass media, and their verdicts tend to be more cautious, and less easily coralled by sub-editors into sensational headlines. It'll be no surprise, then, if the more extraordinary claims of Chang and Halliday stick in the public mind.

From the Leftist Trainspotters list comes a report of the results of some detective work in Sweden's libraries:

From the Leftist Trainspotters list comes a report of the results of some detective work in Sweden's libraries: The Greens are often presented in the right-wing media as an 'extremist' party opposed in principle to imperialism and imperialist war, but their record over the past few years tells another story.

The Greens are often presented in the right-wing media as an 'extremist' party opposed in principle to imperialism and imperialist war, but their record over the past few years tells another story.

Seems there's not much going down in Wellington lately, if the No Right Turn blog is to be believed. No Right Turn recommended a speech on the Treaty of Waitangi by Geoffrey 'constitutional law on the edge' Palmer for 'anyone who has nothing to go to' the weekend before last. Personally, I'd rather go to Sloppy Joe's Whiskey Bar and hear a Dragon covers band than listen to a lecture by the 'progressive' politician who sold Telecom. But when it comes to the Treaty, it's not only the salesman I object to - I don't see why I should buy the product from anyone. Here's a short article I wrote several year ago - I can't remember if it was actually published anywhere - making the Marxist case against the Treaty:

THE TREATY IS A FRAUD

Recently the puppet Karzai government in Afghanistan unveiled a constitution which embedded United States interests in the country and facilitated the US theft of resources from Central Asia. Today in Iraq the US is pushing for the creation of a puppet interim government which Bush wants use to draw up a constitution that will facilitate the plundering ofIraqi resources.

The left has opposed with near-unanimity the Afghan constitution and the moves toward replicating it in Iraq. Paper after paper and speech after speech has pointed out that the Afghan document and the proposed Iraqi government are illegitimate, because they have not been approved by the Afghan and Iraqi peoples, and because they are designed to steal the resources of Afghanistan and Iraq. In New Zealand, the left is joining in this worldwide chorus of denunciation, but remains overwhelmingly in favour of a local constitutional document that was drawn up for the same purpose as Karzai’s constitution, and has the same lack of legitimacy.

The Treaty of Waitangi was never negotiated in good faith, was never democratically approved, and has never benefited the vast majority of either Maori or Pakeha. History shows us that the Treaty grew out of the Declaration of Independence of 1835, a document hastily cooked up by British missionaries and signed by a handful of northern chiefs alarmed by the prospect of the arrival of Charles de Thierry, a Frenchman suffering from delusions of grandeur. De Thierry wanted to set up a private kingdom in the Hokianga, but ended up as a piano teacher in Auckland. The Declaration was supposed to thwart imaginary French designs on New Zealand, not to express some sort of 'good faith' amongst either Maori or British settlers.

Maori nationalism only emerged from the 1850s and 60s, with the growth of pan-tribal movements like the Kingitanga and Kotahitanga. Like Palestinian nationalism, Maori nationalism emerged as a self-defensive measure against the threat presented by an oppressor coloniser. That does not make it any less legitimate, or make the call for the Maori right to self-determination any less urgent. The question is, why on earth does the left need a piece of paper to tell us that Maori are an oppressed and dispossessed people? If the Treaty did not exist, would we not champion Maori land rights? Do we ignore the right to self-determination of the Aborigine peoples, because they never signed a treaty?

Green Party members who have criticised the CWG’s stance over this issue have told us that ‘the Treaty is a reality that cannot be ignored’. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Treaty was ignored by NZ governments for 144 years, and denounced by Maori as a fraud for much of that time. Why did Lange’s Labour government dust off this piece of paper and try to elevate it into a constitutional document in the mid-80s? The truth is that Lange was concerned to contain a growing movement of grassroots Maori who were using direct action protests - the Land Marches of 1975 and 1984, the Bastion Point occupation of 1977-78 were particularly important - to challenge the power of the state and to win back land. Jane Kelsey has documented in great detail the way that Lange’s government co-opted a section of the Maori leadership in classic postcolonial style (Mahuta, Mugabe and Mandela have more than a first letter in common) and dragged the struggle off the streets and into the courts and corporate offices.

Now some Maori are breaking with the co-opters, but the Waitangi myth can still get in the way of direct action. Far too many iwi are wasting their time making submissions to the Waitangi Tribunal over the seabed and foreshore issue, when they should be putting all their energies into organising protest! We applaud those iwi who have boycotted the sham tribunal, and call on the Kiwi left to join them in rejecting the Treaty’s attempt at co-option. The bosses recognise force, not legal niceties or historical myths.

For a less seat of the pants version of my argument about the Treaty's role in the '80s and '90s, check out Matt Russell's 'The Pacification of Contemporary Maori Protest'.