Tuesday, August 30, 2016

When I told a senior New Zealand art critic that I was writing about Emily Jackson he screwed up his face. The art that Jackson produced in such quantities for so many years was, my friend maintained, ‘outdated’. Jackson was a landscape painter, he pointed out, and landscape painting is ‘passe’.

In the decades after World War Two the genre was, he admitted, fashionable, as young men and women like McCahon and Woollaston and Angus wandered through the New Zealand countryside, squinting at hills and headlands and horizons and trying to put them onto canvas and board. But times had changed, the art critic insisted.

What could Jackson’s paintings of the King Country or Otago’s backblocks have to say in the twenty-first century, when New Zealand is an overwhelmingly urban nation plugged into a globalised economy and the worldwide web?

I think that my friend the art critic is wrong, and that Emily Jackson’s landscape paintings are pressingly relevant to contemporary New Zealand. Over at EyeContact I've published an essay comparing the glossy art of the 100% Pure New Zealand Campaign, which exhibits its stuff on billboards and in glossy magazines around the world, with the cryptic paintings of Emily Jackson, who has just published a posthumous book with Atuanui Press.

Thursday, August 25, 2016

Melanesian labourers in New Zealand: unfinished research

I've also been trying to learn about the Melanesians who were brought to New Zealand as indentured labourers in the later decades of the nineteenth century.

About sixty thousand Melanesians, almost all of them from Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands, were brought to Queensland to toil in that state's sugarfields in the nineteenth century. Today, the descendants of some of these 'blackbirded' labourers make up Australia's South Sea Islander community. In Vanuatu and in the Solomons many families remember ancestors who suffered in Queensland. Historians have told the story of Queensland's bonded labourers in essays and books and documentary films.

But the stories of the Melanesians who were brought to New Zealand have seldom been told. Only a relatively small number of Melanesians came to this country, and few of them stayed here permanently. But their presence prompted debates in the media and in parliament, and led to the creation of an historic set of photographs.

Next month I'll be travelling to Vanuatu. I'm hoping to place a set of papers relating to New Zealand's Melanesian labourers in the archives of the famous Vanuatu Cultural Centre.

The largest group of Melanesian labourers arrived in New Zealand in 1870 from the island of Efate. Reproduced below is a timeline that tries to explain how and why the Efateans came to New Zealand, and what they experienced here. The timeline is still very incomplete, and I've sprinkled it with research questions.

I've shown the timeline to my friend Christine Liava'a, who has been researching the same subject, to a few members of New Zealand's ni-Van community, and to Clive Moore, the Australian academic who has spent his career studying the indentured labourers of Queensland. If anyone else would like to discuss or to see some of the material I've gathered on Melanesian labourers in New Zealand and on blackbirding in general, then they can e mail me at shamresearch@yahoo.co.nz

The Lulu labourers and New Zealand: an unfinished timeline

12 July 1869

The Daily

Southern Cross reports that a ‘large scale’ flax mill will soon be built by

‘Messrs Walker and Reid’ in the Hokianga. The mill will stand at Waiarohia, a

place halfway between Opononi and Omapere near the southern head of Hokianga

harbor. Many mills are being built around the country, as prices for flax rise

overseas.

6 December 1869

The New Zealand

Herald reports that Walker and Reid have held a large party to celebrate the

opening of their mill at Waiarohia, and notes that the two men already have

access to eight hundred acres of flax plants.

20 December 1869

A schooner named Lulu

is launched at Onehunga’s port, in a ceremony attended by some of Auckland’s

wealthiest businessmen. The daughter of Thomas Russel, a key proponent of the

Waikato War and the founder of the Bank of New Zealand and the legal firm

Russel McVeigh, has the honour of breaking a champagne bottle against the

boat’s hull. Francis Cadell, an early explorer of Australia’s rivers who

commanded a ship during the Waikato War, is named as the owner of the Lulu, though it is unlikely he would

have been able to pay for the ship’s construction. Cadell will soon return to

Australia, and in 1876 he will be arrested and removed from Western Australia

for enslaving Aboriginals.

January 1870

The Auckland businessman Edward Brissenden leases

nearly four hundred acres beside the Waitakere River in the Te Henga area of

West Auckland. Brissenden will spend eight months building and running a mill

on the land, before a legal challenge to his right to lease the land forces him

to end operations.

13 March 1870

After making a few voyages along the New Zealand

coast, the Lulu leaves Picton bound

for the New Hebrides. The schooner carries a man named Young, who is charged

with recruiting workers for Edward Brissenden’s flax mill at Waitakere. The Lulu stops at Norfolk Island on the 22nd

of March, and reaches Noumea two days later.

April 1870

The Governor of New Zealand, Sir George Bowen, tours

Northland, and takes a cruise down the Hokianga harbour. Reports of Bowen’s

cruise mention that the other passengers in the boat recognised the flax mill

of Waiarohia as they moved towards the heads of the harbor.

April 1870

The Lulu reaches

Aneityum, in the far south of the New Hebrides. The locals refuse contact, and

so the vessel continues to Tanna, which

it reaches on the 9th of April. Large numbers of Tannese board the ship to

trade, but they refuse offers of recruitment, so the Lulu pushes on to Efate, which it reaches on the 13th.

But the Efateans, too, refuse recruitment, telling the Lulu’s crew that they have been mistreated after journeying to Australia

to work.

Two Tannese and one Efatean do join the ship as interpreters, and

chiefs at Efate agree to produce recruits in exchange for rewards. The Lulu encounters a schooner from Sydney

called the Zephyr, which has been

trying unsuccessfully to recruit labour for Fiji’s canefields, then moves

north, through the small islands near Efate to Ambrym, Malekula, and Pentecost.

At Pentecost crew

members land to try to recruit, but have to retreat when arrows are fired at them. They escape without injury, and the Lulu

returns to Efate. On the 27th of April, at Havannah harbour,

nine men board the ship. Twelve men join the boat at Mele Bay, and two at

Pango peninsula. The Lulu sails south

with twenty-seven recruits, stops at Tanna to pick up a European passenger named

Miss Chapman, then leaves the New Hebrides.

25 April 1870

John Coleridge Patteson, the Anglican Bishop of

Melanesia and a loud opponent of blackbirding, arrives in Auckland to recover

from an illness. Patteson is soon living with Governor George Bowen in central

Auckland’s Government House. At least one of Patteson’s biographers has suggested that he was aware of the controversy around the Lulu’s voyage that

began after the ship arrived in Auckland in May 1870.

Question: did Patteson influence

Bowen’s attitude to blackbirding? And do documents that show him intervening in

the arguments about the Lulu and its passengers survive in the massive archive

at the Kinder Library of St Johns theological college in East Auckland?

20 May 1870

The Lulu

arrives at Auckland’s Waitemata port. According to a report in the Daily

Southern Cross, it carries ‘twenty-seven South Sea Islanders’ who ‘are to be

employed at a flax mill in Waitakere’ for a ‘period of three years’ after which

‘they must be returned to their homes’.

21 May 1870

The Daily

Southern Cross publishes a very long and detailed account of the journey of

the Lulu, which it says is based upon

a diary kept by ‘Captain Ponsonby’ whom it describes as the ship’s ‘navigator’. Ponsonby

admits that the Lulu’s crew used ‘douceurs’, or bribes, to secure labourers

from Efate and Nguna, after visiting all of the major islands of the New

Hebrides and failing to recruit workers.

Question: how far can we trust this text,

when we remember that other New Zealand mariners involved in blackbirding, like

the notorious Thomas McGrath, who took slaves at two Tongan islands in 1863,

offered false details of their voyages to the media? On the other hand, does

Ponsonby’s apparently incriminating admission of bribery suggest that he was

being honest?

24 May 1870

The Daily

Southern Cross editorialises against ‘the introduction of contract

labourers from the South Sea Islands to New Zealand’, claiming that it is

‘impossible to suppose’ the men on the Lulu came here ‘voluntarily’, and

predicting that these ‘Pagan and Debased’ visitors ‘will toil at their masters’

mills’ and be ‘scantily fed and clothed’.

24 May 1870

The Daily

Southern Cross publishes, under the headline ‘Polynesian Labour for Auckland’, a letter condemning imported South Sea Island workers as a threat to

the economy of New Zealand. According to the correspondent, who signs himself

Operarius, which is Latin for ‘Worker’ or ‘Working’, South Sea Islanders are

not paid enough and do not spend enough time in their host countries to

stimulate the economy there. New Zealand can only become prosperous if it

imports white workers, lets them stay permanently, and pays them reasonable

wages.

Question: was Operarius

expressing the views of New Zealand’s embryonic trade union movement? We know

that, during the early decades of the twentieth century, New Zealand’s unions

frequently took an anti-immigrant line, supporting the White Defence League and

at one point warning of the danger of indentured labourers from Niue.

10 June 1870

Wellington’s Evening

Post editorialises against the importation of South Sea Island

labourers to New Zealand. The Post compares

the labourers imported by the Lulu to

slaves, and calls for legislation, so that the importation of more labourers

can ‘be nipped in the bud’.

30 June 1870

Sir George Bowen, the Governor of New Zealand, sends a

dispatch to London describing the arrival of the Lulu and expressing opposition to the ship’s mission. Bowen

attaches a memorandum from New Zealand Premier William Fox promising an

investigation into the Lulu and into

the issue of imported labour.

c. July 1870

After the closure of the mill at Waitakere, eleven of

the ni-Vanuatu are sent to the flax mill Walker and Reid are running in the

Hokianga, while twelve are despatched to Puriri, a settlement near Thames,

where Edward Brissenden has another mill.

14 July

1870

The Daily

Southern Cross published a letter that claims ‘a certain schooner’ is about

to leave New Zealand for the islands on a blackbirding mission. The

correspondent, who signs himself ‘Old Colonist’, threatens to publish the names

of the ‘parties’ to this venture.

21 September 1870

The New Zealand Herald publishes a long article called

‘Disgusting Results of Imported South Sea Labour’. The Herald suggests that the ‘niggers’ brought to Auckland on the Lulu

may have been kidnapped. Instead of showing sympathy for the ni-Vanuatu,

though, the Herald condemns them as ‘woolly barbarians’ whose ‘manners and

faults’ are an ‘outrage’ to New Zealand. The Herald claims it has received

letters that describe the South Sea Islanders exhuming the bodies of animals

that have died from disease, and devouring these animals ‘greedily’. It also

repeats claims that the islanders have ‘scoured the creeks and landed putrid

carrion’ on which ‘they have feasted exaltingly’. The Herald suggests that the

islanders’ employers have not looked after them, and that they have become

‘naked and depressed’ and a ‘public nuisance’.

Question: is the Herald’s disturbing article evidence that the

ni-Vanuatu had been neglected, or even abandoned, in the middle months of 1870,

when the flax mill where they were supposed to work at Waitakere was closing

down?

26 September 1870

A fire so bright that it can be seen from Auckland

destroys Edward Brissenden’s flax mill at Puriri. The Thames Star reports that the gutted building ‘was of large extent’ and employed ‘about thirty

men, besides boys’. The Star says that ‘one man was severely burnt on the

hand while trying to save some property’. An article in the Daily Southern

Cross says that ‘employees of the mill…rendered valuable assistance’ during

the struggle against the fire.

The ni-Vanuatu who had been labouring at Puriri

are relocated to Auckland, where they are put to work on the Kohimarama estate

of businessman JS McFarlane, who was a guest at the launch of the Lulu, and at the Epsom residence of

Edward Brissenden. Three of the men – ‘One o’clock’, ‘Charley’, and ‘Monday’ –

were eventually moved north to the mill at Waiarohia.

Question: was it a ni-Vanuatu

labourer who was badly burned?

13 January

1871

A roundup of news from the Hokianga published in the Daily Southern Cross mentions that

‘Walker and Reid’s mill continues to turn out a few tons occasionally’, and

suggests that ‘if this establishment, with its South Sea Islanders as labourers

cannot be made profitable’ then the flax industry has little future.

c. June 1871

Daniel Louis Mundy, one of New Zealand’s few

professional photographers, makes a tour of Northland in search of images, and

stops at Waiarohia long enough to take a number of photographs at the flax

mill. The mill’s ni-Vanuatu workers appear in a number of Mundy’s photographs.

Mundy does not mention the ni-Vanuatu in the titles to his photographs, and

they often seem present simply to give his portraits of flax plants and

machinery a sense of scale.

10 June 1871

The Lulu,

which had been busy moving labourers to and from Fiji, hits a reef off Espiritu

Santo and is wrecked. No labourers are aboard the ship when it founders.

The

crew boards a lifeboat, which is soon approached by canoes filled with

hostile islanders. After avoiding arrows, the crew of the Lulu puts ashore at Lisbon Point

mission station and are rescued by the Presbyterian ship Dayspring, which is anchored there.

21 September 1871

Coleridge Patteson is killed on the small island of

Nukapu by locals taking revenge for a recent blackbirding raid. Patteson’s

death prompts an outcry against blackbirding in Australasia and in Britain, and

new laws are soon passed to try to end the practice. Often, though, these laws

will be poorly enforced.

c. December

1871

A ni-Vanuatu labourer identified as ‘Kuri’ dies of

consumption at Waiarohia. Local coroner and magistrate Spencer von Sturmer had

been giving Kuri medicine, and records his death.

17 April 1872

John Thomson, head of Auckland’s armed constabulary,

submits a report to the New Zealand government after visiting the ni-Vanuatu

working in Auckland and in the Hokianga. Thomson describes the huts the

labourers have built in the Hokianga as an alternative to the accommodation

their employers offered, and explains how they supplement their rations by

gardening and fishing. Thomson considers that the ni-Vanuatu are ‘comfortable’,

but relays their complaint that they have been made to work too long in New Zealand.

They seem to have believed they were obliged to work for one year, but their

employers insist they signed up for three years. Thomson does not consider that

he has the authority to remove the men from their employers. His report is

forwarded to Governor Bowen.

10 May 1873

The Daily

Southern Cross carries an account of a visit to the Hokianga. The anonymous

traveller visited the flax mill at Waiarohia, and was given a tour by its

manager, ‘Mr Charles Clark’, who explained that he had been using ‘South Sea

Islands labour’. These workers had been ‘very comfortable’ in the

Hokianga: they are ‘going on a trip’,

but some ‘want to come back…bringing their wives with them’. Before they left,

the South Sea Islanders ‘favoured the locals with some of their dances’.

Questions:

how can this report be reconciled with the complains the ni-Vanuatu made to Jon

Thomson about the length of time they had been made to work in the Hokianga?

Which dances would the ni-Vanuatu have performed, and what would their meaning

have been? Can we get a sense of the dances they would have performed by

reading the accounts of Efatean culture produced late in the nineteenth century

by missionaries like Daniel McDonald?

6 June 1873

The New Zealand Herald reports that ‘about a dozen

South Sea Islanders left a few days ago in the schooner Colonist’ after having ‘served periods from one to three years in

this province – principally in the flaxmills at Hokianga and Waikato’. The

Herald claims that the men are ‘satisfied’ with their lot, and says that some

of them plan to return to New Zealand. It reports that before leaving on the

Colonist they ‘laid out what money they had’ to buy goods that would be

valuable in the islands. The Herald,

which only a couple of years earlier condemned the South Sea Islanders as

‘woolly barbarians’ concludes its article with the sanguine sentence ‘they came

here penniless, but go back traders on a small scale’.

Question: what goods did the

honeward bound South Sea Islanders buy? Often labourers returning from the

plantations of Queensland would send their precious wages on guns, which were

scarce and very valuable in Melanesia.

August 1873

The photographs that Daniel Mundy took at Waiarohia

are included in New Zealand’s contribution to the Vienna International

Festival, a huge event modelled on the Great Exhibition held at London’s

Crystal Palace in 1851.

10 August

1873

The Colonist

returns to New Zealand, putting in at the Port of Russell because of ‘stress of

weather’.

Question: did the Colonist

succeed in dropping the men of Efate and Nguna home? Efate was enjoying a

period of peace in the 1870s, and in the area around Port Havannah, where many

of the labourers had embarked, palangi newcomers had established relatively

good relations with locals. It may well be, then, that the Colonist was able to complete its mission.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Monday, August 22, 2016

One day, many wars

It is good to see the government promising a national day of commemoration for the New Zealand Wars, the conflicts that killed thousands of people in these islands between 1843 and 1916.

The New Zealand Wars were intermittent, regional, and very complex. Often they had more than two sides.

The New Zealand Wars were intermittent, regional, and very complex. Often they had more than two sides.

When Te Kooti waged his guerrilla war in the central North Island in the late 1860s and early '70s, for example, he found himself fighting not only the colonial army controlled by the Pakeha government in Wellington, but the forces of the Ngati Porou and Te Arawa peoples, who had chosen for their own reasons to make an alliance with the Crown. As the war developed Te Kooti made his own alliances, winning support from the Tuhoe people of the Ureweras and from sections of the Tuwharetoa people of the Taupo region.

Te Kooti even found some Pakeha supporters. A group of Irish Fenians sold him ammunition, and a trade unionist and anarchist named Arthur Desmond was almost lynched after performing a poem in his honour in a Pakeha settlement on the East Coast. Despite the urgings of Wellington, the British government, which had become increasingly critical of New Zealand's colonists, refused to support the struggle against Te Kooti.

The outcomes of the New Zealand Wars were also complex. Many iwi suffered devastating land confiscations in the aftermath of their struggles with the Crown. The Tainui peoples lost more than two million acres in the aftermath of the conquest of the Waikato. Crown land confiscations were justified as punishment for rebellion, but they were motivated by the greed of property speculators. Some iwi that had fought hard against the invasion of the Waikato saw their lands untouched, because they were of little economic value, while iwi that had remained neutral but lived on desirable land, like Ngati Kahukura of Waiuku, suffered confiscations.

A few iwi were able to emerge from the New Zealand Wars with their lands relatively intact. After a civil war in which supporters of an alliance with Pakeha were triumphant, Ngati Porou contributed men to the struggle against Te Kooti. After that war had finished the iwi held on to the weapons it had been given to fight Te Kooti, and threatened to use them against any Pakeha who tried to take their lands. The government in Wellington shelved plans to push settlers into Ngati Porou's region.

When it organises commemorations of the New Zealand Wars, the state should make a distinction between the facts of history and the interpretation of these facts.* Kiwis should be given the facts of their country's nineteenth century history, and encouraged to debate the meaning of these facts. The details of Te Kooti's life are clear and dramatic, but different people in different places will inevitably have different opinions on the meaning of his life. For some commentators, Te Kooti has been a fanatic and a terrorist; for others, he has been a freedom fighter; for still others, he was a misunderstood man of peace.

The commemorations of the New Zealand Wars could be an opportunity for us all to learn more not just about the facts of our country's history but about the many ways that the past can be viewed.

The commemorations of the New Zealand Wars could be an opportunity for us all to learn more not just about the facts of our country's history but about the many ways that the past can be viewed.

Although the New Zealand Wars deserve their own day of commemoration, they should also be remembered on Anzac Day. The first Anzacs fought not at Gallipoli but in the Waikato and Taranaki Wars of the 1860s, when many hundreds of soldier-settlers from Victoria and New South Wales joined colonial New Zealand troops in their battles against Maori.

*Admittedly, hard and fast distinctions between fact and interpretation are often difficult to make.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

*Admittedly, hard and fast distinctions between fact and interpretation are often difficult to make.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Friday, August 19, 2016

The lost land of aute

Over at EyeContact the Panmure psychogeographer Richard Taylor has made a typically thorough response to my essay about Nikau Hindin, the young artist who is trying to reanimate the ancient Maori art of tapa making.

When I told friends about Nikau Hindin's recent exhibition at Manurewa's Nathan Homestead gallery a lot of them thought I was hoaxing. They were sure that Maori had never made tapa. Even when I showed them some promotional material for the show, I suspect that they thought it might be some sort of 'Forgotten Silver'-style joke. The notion of Maori tapa confuses many of our categories, it seems.

Coincidentally, I was reading David Simmons' fascinating book Greater Maori Auckland this week, and I found a chapter about the flat and sandy islands that once existed off Awhitu and in the Kaipara harbour. These 'lost lands' were slowly eaten by wind and water, and now exist only in a melancholy photograph and some oral traditions. I'd known about the lost land of Paorae, thanks to this article by James Cowan, but had never heard of the sunken Kaipara island of Taporapora.

Simmons says that Taporapora, which is today no more than a mangrove bank off a tiny bach village at the end of a peninsula in the central Kaipara, was once the home of a whare wananga and of a famous plantation of aute. It was interesting to learn this story, because several aute beaters have been found close to Taporapora, in the mud-choked mouths of the rivers that feed the Kaipara harbour. Oral tradition and archaeology seem, then, to support one another.

Simmons says that Taporapora, which is today no more than a mangrove bank off a tiny bach village at the end of a peninsula in the central Kaipara, was once the home of a whare wananga and of a famous plantation of aute. It was interesting to learn this story, because several aute beaters have been found close to Taporapora, in the mud-choked mouths of the rivers that feed the Kaipara harbour. Oral tradition and archaeology seem, then, to support one another.

I wonder whether we couldn't also bring palaeoclimatology to the table, and ask whether a microclimate helpful to the raising of tropical plants like aute might have existed at Taporapora half a millennium or so ago.

Microclimates certainly exist in the Kaipara region today: olives and other Mediterranean crops are grown on the Tinopai peninsula, which extends into the harbour from the north, and is known for its warm and dry weather.

David Simmons reports that different groups settled Taporapora at different times. The second group to settle on the island brought aute, and presumably wielded aute beaters. In my essay on Nikau Hindin I report linguist Roy Harlow's belief that different Eastern Polynesian peoples settled Aotearoa at different times, before coalescing and becoming the ancestors of Maori. Harlow detects a trace of Mangaian in the dialects of regions like the Kaipara.

Perhaps a fragment of tropical Polynesian society established itself and persisted in a stable state for some time, on the atoll-like island of Taporapora, centuries before the emergence of what we know today as Maori culture?

I wish our archaeologists had a submarine, so that they could look at the ancient lands of Taporapora and Paorae.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Microclimates certainly exist in the Kaipara region today: olives and other Mediterranean crops are grown on the Tinopai peninsula, which extends into the harbour from the north, and is known for its warm and dry weather.

David Simmons reports that different groups settled Taporapora at different times. The second group to settle on the island brought aute, and presumably wielded aute beaters. In my essay on Nikau Hindin I report linguist Roy Harlow's belief that different Eastern Polynesian peoples settled Aotearoa at different times, before coalescing and becoming the ancestors of Maori. Harlow detects a trace of Mangaian in the dialects of regions like the Kaipara.

Perhaps a fragment of tropical Polynesian society established itself and persisted in a stable state for some time, on the atoll-like island of Taporapora, centuries before the emergence of what we know today as Maori culture?

I wish our archaeologists had a submarine, so that they could look at the ancient lands of Taporapora and Paorae.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

Who needs a drug-free Olympics?

It was marvellous to see Fiji beat the Poms and win a first gold medal for the Pacific last week in Rio. It was even better to see the Fijians celebrate their triumph by drinking yaqona (or kava, as it is known in this part of the Pacific) in front of thousands of spectators. We've heard a lot about the necessity of disentangling drugs from the Olympics, and athletes in Rio have endured all sort of peculiar tests for traces of substances deemed illegitimate by the guardians of their sports. Curiously, though, nobody seemed to object to a group of gold medallists consuming a venerable narcotic in full view of fans and cameras.

Kava, it seems, is a drug that can hide in plain sight. A couple of years ago demonstrators up and down New Zealand demanded, and eventually got, a ban on the sale of synthetic cannabis. Our media covered the debate over synthetic pot in great detail, visiting the shops were the stuff was sold and interviewing various users in various states of health. But neither the campaigners against drugs nor the advocates for synthetic pot nor the media ever seemed to notice that scores of ordinary corner dairies in south and west Auckland sell bags of an imported, completely unregulated narcotic every day. Kava is used by many members of Auckland's huge Pacific Islands community, and by a few palangi who have discovered its pleasant effects.

I suspect that the protesters and the media ignore kava because it doesn't fit some of the stereotypes they hold about recreational drugs. Kava users don't end up holding up dairies or begging outside the Warehouse for money to buy another fix. They do not seclude themselves shamefacedly from the rest of society when they enjoy the drug. Kava drinking is an activity that ornaments rather than disrupts lives.

I hope that the Fijians' very public endorsement of kava will prompt greater interest in the drug outside the Pacific. I can't help thinking that regions like Europe and the Middle East would be better off if their populations took to ingesting some of the drug at the end of the day. Kava relaxes its users without addling their brains, and makes them sociable yet not voluble. It is not surprising that Melanesians often use the drug in ceremonies designed to settle disputes and ameliorate bad feelings. Imagine how much more pleasant the bars and streets of Bolton or Scunthorpe would be at two o'clock on a Saturday morning, if punters had been drinking kava rather than lager. Picture how much more smoothly Middle East peace negotiations might proceed,if they were held around a bowl of kava.

I wrote a little about the kava culture of Tonga here.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Friday, August 12, 2016

From tapa to Taua

Over at EyeContact I've published an essay about Nikau Hindin, who has been trying to revive Maori tapa, an artform dead for half a millennium. I talk about the different challenges that Nikau and the ngatu painters of Tonga face, and use a quote from my troublemaking mate Justin Taua to try to show that Nikau's project is not just an exercise in recreating the past, but has important political implications.

[Poste by Scott Hamilton]

Tuesday, August 09, 2016

Trump, the Pacific, and unintended consequences

On his popular Kiwiblog, the National Party pollster and advisor to John Key David Farrar is vainly trying to convince his audience that Donald Trump should not become president of the United States. Many of Kiwiblog's readers are social conservatives partial to conspiracy theories about ethnic minorities, and Trump's orations against Muslims and Mexicans have delighted them.

I haven’t seen any of Farrar's readers discuss how a Trump presidency might affect New Zealand’s traditional role in the Asia and Pacific regions.

Since World War Two Australia and New Zealand have been sheriff's deputies for the United States in the Pacific. Our navy and army exercise regularly with their American counterparts, despite our anti-nuclear policy, and we formulate and execute interventions in Asian and Pacific nations together. When they face serious issues, Kiwi diplomats in Pacific nations where America lacks representation - nations like Tonga and the Solomon Islands - follow policies developed with Canberra and Washington. The Australian and New Zealand military and police interventions in nations like Timor-Leste, Tonga, and the Solomons were all made in line with American policy, and with the moral support of America.

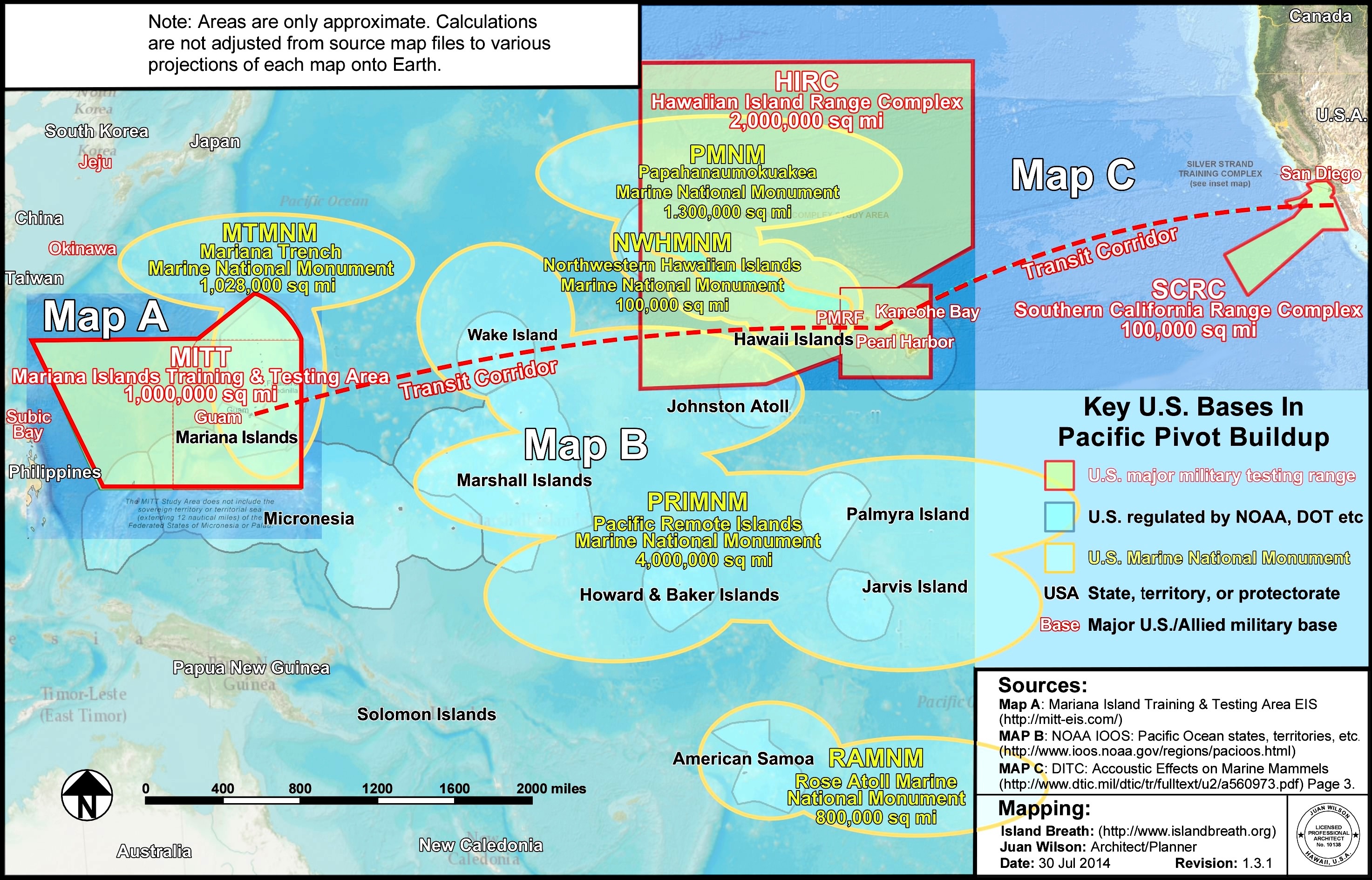

In recent years the Anzac nations and America have been trying to stymie the spread of Chinese influence through the Pacific. The Obama administration has tipped more money into the region, and consolidated its military bases on islands like Guam and Okinawa. Obama has spoken of shifting the focus of American foreign policy from Europe and the Middle East to Asia and the Pacific. The recent visit of Obama's deputy Joe Biden to New Zealand was a reminder of the cosy relationship between this country and the United States. Biden used his visit to warn China that the United States remained a 'Pacific power', and was not about to vacate the region.

Trump may have fluid or incoherent opinions on many other subjects, but his views on foreign policy have been clear and consistent for decades. He dislikes the many treaties that make America responsible for the defence of smaller and weaker nations, and he admires the size and power of China and Russia. On the campaign trail this year Trump has called the NATO alliance a drain on American resources, and dismissed America's military alliances with Japan and South Korea for the same reason. Trump has made his admiration for Vladimir Putin clear, and has said that he is keen to reach a better understanding with China's leaders.

It would not be at all surprising if president Trump junked the Obama-Clinton policy of confronting China in the Asia and Pacific regions. He would be especially likely to turn away from the strategically unimportant South Pacific, and let China complete its economic colonisation of nations like Tonga and Fiji. If Trump thinks American military bases in Europe and on the Korean peninsula are unnecessary, then he is unlikely to have much enthusiasm for maintaining facilities in places like New Zealand or the Marshall Islands or American Samoa.

If Trump turned his back on the Pacific then the New Zealand and Australian governments would face a choice. They would either have to maintain a policy of confronting China on their own, which would be very difficult, or else reach some sort of rapprochement of their own with the Chinese. Either way, they could not count on the guidance and materiel of their American cousins.

They might object to numerous other aspects of a Trump presidency, but few people on the New Zealand left would be too upset by an American withdrawal from the Pacific. It is New Zealand's political and defence establishments that would have a headache. David Farrar's alarm at Trump's rise is understandable.

One of the stranger unintended consequences of a Trump presidency might be the emergence, for the first time in one hundred and thirty years, of an independent New Zealand foreign policy.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

One of the stranger unintended consequences of a Trump presidency might be the emergence, for the first time in one hundred and thirty years, of an independent New Zealand foreign policy.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Friday, August 05, 2016

A quick note on Tonga's new crisis

I had a chat on twitter a few months ago with Michael Field, the Pacific journalist and author of a classic study of New Zealand's colonial occupation of Samoa. Field has been an astringent commentator on Tongan affairs, and for many years he was banned from the kingdom.

When I asked him whether he had plans to write a book about the Friendly Islands, Field said he'd like to publish a study of the democratisation of the kingdom, but that he didn't think the time was quite right. Tonga's royal family and class of nobles lost a lot of power in 2012, when the country adopted a revised constitution that gave commoners a majority of seats in parliament for the first time and stripped the monarch of his right to form governments. But Field told me that he didn't think the nine nobles who still sit in Tonga's parliament were quite ready to concede power to the seventeen commoners who sit alongside them. 'They'll push back', he warned.

It looks like Michael Field was right, because this week Lord Vaea, a long-time member of the Tongan parliament, has been preparing to put a motion of no confidence in 'Akilisi Pohiva, the leader of the Friendly Islands Democratic Party who became Prime Minister late in 2014. Lord Vaea is in Auckland with Pohiva, on what must be a rather awkward state visit, but his fellow nobles back in Nuku'alofa have been telling journalists and foreign diplomats that Pohiva must go. Vaea says a vote of no confidence will be 'a priority' when he returns to Tonga.

In an interview on Radio New Zealand this morning, Michael Field blamed the move against Pohiva on the elderly leader's increasing frailty, on anger over the Tongan government's desire to sign a United Nations resolution on the rights of women, on frustration at Tonga's 'enormous poverty', and on the refusal of the nobility to accept the dictates of the country's commoners.

The nine nobles in Tonga's parliament have tended to act as a bloc, and are probably united now in wanting to get rid of Pohiva. The nobles were elected by a few dozen of their peers, and are thus insulated from public opinion, but they must persuade five of the popularly elected commoner MPs to their side if they want to vote Pohiva out of office. Field is not sure that they will be able to do this.

Michael Field is hardly alone in believing that Tonga's democratisation is an unfinished story. 'Akilisi Pohiva and his supporters in the country's media have often lamented the way that the revised 2012 constitution gives nobles a third of the seats in parliament by right. Pohiva has at times talked of abolishing the seats, and at other times suggested that they should at least be popularly elected.

If they move as a bloc against the Pohiva government with light support from commoner MPs, then Tonga's nobles will be putting themselves in a dangerous situation. Defenders of Tonga's constitutional arrangements like Tevita Motulalo, with whom I had a less than amicable discussion back in 2014, have insisted that the nobles ought to have places reserved for them in parliament because they represent the kingdom's traditions and culture, and can act as apolitical advisers to representatives of the commoners. That argument was always nonsense, and a power grab by the nobility will expose it as nonsense to every Tongan. Tongans took to the streets in the tens of thousands in 2005 and 2006 to demand democracy; it wouldn't be surprising to see them take to the streets again, in defence of their popular Prime Minister. The reforms of 2012 could turn into the revolution of 2016.

Footnote: In this essay for EyeContact I tried to give a sense of how the struggle between Tonga's democrats and authoritarians plays out in everyday life, and in art.

Update: looks like the vote of no confidence will come on August the 15th.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

When I asked him whether he had plans to write a book about the Friendly Islands, Field said he'd like to publish a study of the democratisation of the kingdom, but that he didn't think the time was quite right. Tonga's royal family and class of nobles lost a lot of power in 2012, when the country adopted a revised constitution that gave commoners a majority of seats in parliament for the first time and stripped the monarch of his right to form governments. But Field told me that he didn't think the nine nobles who still sit in Tonga's parliament were quite ready to concede power to the seventeen commoners who sit alongside them. 'They'll push back', he warned.

It looks like Michael Field was right, because this week Lord Vaea, a long-time member of the Tongan parliament, has been preparing to put a motion of no confidence in 'Akilisi Pohiva, the leader of the Friendly Islands Democratic Party who became Prime Minister late in 2014. Lord Vaea is in Auckland with Pohiva, on what must be a rather awkward state visit, but his fellow nobles back in Nuku'alofa have been telling journalists and foreign diplomats that Pohiva must go. Vaea says a vote of no confidence will be 'a priority' when he returns to Tonga.

In an interview on Radio New Zealand this morning, Michael Field blamed the move against Pohiva on the elderly leader's increasing frailty, on anger over the Tongan government's desire to sign a United Nations resolution on the rights of women, on frustration at Tonga's 'enormous poverty', and on the refusal of the nobility to accept the dictates of the country's commoners.

The nine nobles in Tonga's parliament have tended to act as a bloc, and are probably united now in wanting to get rid of Pohiva. The nobles were elected by a few dozen of their peers, and are thus insulated from public opinion, but they must persuade five of the popularly elected commoner MPs to their side if they want to vote Pohiva out of office. Field is not sure that they will be able to do this.

Michael Field is hardly alone in believing that Tonga's democratisation is an unfinished story. 'Akilisi Pohiva and his supporters in the country's media have often lamented the way that the revised 2012 constitution gives nobles a third of the seats in parliament by right. Pohiva has at times talked of abolishing the seats, and at other times suggested that they should at least be popularly elected.

If they move as a bloc against the Pohiva government with light support from commoner MPs, then Tonga's nobles will be putting themselves in a dangerous situation. Defenders of Tonga's constitutional arrangements like Tevita Motulalo, with whom I had a less than amicable discussion back in 2014, have insisted that the nobles ought to have places reserved for them in parliament because they represent the kingdom's traditions and culture, and can act as apolitical advisers to representatives of the commoners. That argument was always nonsense, and a power grab by the nobility will expose it as nonsense to every Tongan. Tongans took to the streets in the tens of thousands in 2005 and 2006 to demand democracy; it wouldn't be surprising to see them take to the streets again, in defence of their popular Prime Minister. The reforms of 2012 could turn into the revolution of 2016.

Footnote: In this essay for EyeContact I tried to give a sense of how the struggle between Tonga's democrats and authoritarians plays out in everyday life, and in art.

Update: looks like the vote of no confidence will come on August the 15th.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Tuesday, August 02, 2016

A very lost Hamilton

Last week a copy of the first ever trilingual anthology of Maori poetry turned up in my letterbox. Twelve Heavens/Nga Rangi Tekau-Ma-Rua/Doce Cielos runs to 136 pages, and presents the work of eight contemporary Maori. A stickynote directed me to pages 64-66, where three different versions of a poem about myself waited. Unfortunately, the poem, which was written by my old mate Vaughan Rapatahana, isn't entirely complimentary. Here are its Maori and English incarnations:

ha! haumata

For Scott Hamilton

ha! hamutana

kei whea koe e hoa?

e titiro ana ahau mo

he hamutana

te taima katoa,

egari ko tahi hamutana anake kei konei -

he taone nui

i roto te rohe of Waikato.

ko kaore he tane ki tenei ingoa,

kaore he tane o nga whakataurangi nui

me he waha e taurite!

kei whea koe e hoa?

ko te kirikiroa tino ngaro koe

e kautahoe

ki tau moana o nga kupu nui.

hey! hamilton

For Scott Hamilton

where are you, friend?

I look for a hamilton

all the time

but there is only one here

a big town in the waikato district.

there is no man with this name

no man with many promises

and a mouth to match!

where are you friend?

you are a very lost Hamilton

swimming

in your ocean of big words

Vaughan might be referring to my repeated failure to visit him in Morrinsville since he returned from Southeast Asia and settled in that charming town a couple of years ago. When we walked the length of the Great South Road last December, Paul Janman and I hoped that Vaughan would drive down, ditch his car, and join us for a few kilometres. But Vaughan is teaching in Morrinsville, and he was too busy for psychogeography. He told us he'd shout us a coffee if we made a detour to his new hometown, but that would have added a couple of days and a dozen or so blisters to our journey.

Not only have I failed to visit Vaughan - I've failed to publish him. He sent me a long and interesting essay about Manila, the city where he spent years in exile, a couple of years ago, and asked if I wanted to post in on this blog. I told him I would, and promptly misplaced the text. I've relocated it today, and will stick it up tomorrow.

But I haven't neglected Vaughan Rapatahana entirely. I posted this essay about his poetry in 2012, ran a short interview with him in 2011, and in the same year republished his fascinating article about teaching on the hollowed-out island of Nauru.

Nor have I neglected Morrinsville completely. I published this essay about the Maungakawa ranges, which rise south of the town and are an old stronghold of the Maori King Movement, in 2011. I'm revising the essay for inclusion in my forthcoming book about the Great South Road.

Vaughan has a habit of sending me e mails written entirely in te reo Maori; I tend to feel embarrassed by my inability to decipher them. This year, though, I've been studying Tongan, a language Vaughan claims to understand very imperfectly. I've been looking forward to being able to reply to one of his Maori missives with a long and incomprehensible epistle in Tongan!

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

ha! haumata

For Scott Hamilton

ha! hamutana

kei whea koe e hoa?

e titiro ana ahau mo

he hamutana

te taima katoa,

egari ko tahi hamutana anake kei konei -

he taone nui

i roto te rohe of Waikato.

ko kaore he tane ki tenei ingoa,

kaore he tane o nga whakataurangi nui

me he waha e taurite!

kei whea koe e hoa?

ko te kirikiroa tino ngaro koe

e kautahoe

ki tau moana o nga kupu nui.

hey! hamilton

For Scott Hamilton

where are you, friend?

I look for a hamilton

all the time

but there is only one here

a big town in the waikato district.

there is no man with this name

no man with many promises

and a mouth to match!

where are you friend?

you are a very lost Hamilton

swimming

in your ocean of big words

Vaughan might be referring to my repeated failure to visit him in Morrinsville since he returned from Southeast Asia and settled in that charming town a couple of years ago. When we walked the length of the Great South Road last December, Paul Janman and I hoped that Vaughan would drive down, ditch his car, and join us for a few kilometres. But Vaughan is teaching in Morrinsville, and he was too busy for psychogeography. He told us he'd shout us a coffee if we made a detour to his new hometown, but that would have added a couple of days and a dozen or so blisters to our journey.

Not only have I failed to visit Vaughan - I've failed to publish him. He sent me a long and interesting essay about Manila, the city where he spent years in exile, a couple of years ago, and asked if I wanted to post in on this blog. I told him I would, and promptly misplaced the text. I've relocated it today, and will stick it up tomorrow.

But I haven't neglected Vaughan Rapatahana entirely. I posted this essay about his poetry in 2012, ran a short interview with him in 2011, and in the same year republished his fascinating article about teaching on the hollowed-out island of Nauru.

Nor have I neglected Morrinsville completely. I published this essay about the Maungakawa ranges, which rise south of the town and are an old stronghold of the Maori King Movement, in 2011. I'm revising the essay for inclusion in my forthcoming book about the Great South Road.

Vaughan has a habit of sending me e mails written entirely in te reo Maori; I tend to feel embarrassed by my inability to decipher them. This year, though, I've been studying Tongan, a language Vaughan claims to understand very imperfectly. I've been looking forward to being able to reply to one of his Maori missives with a long and incomprehensible epistle in Tongan!

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]