Find the theory boring? Try the play...

I'm grateful to sci fi socialist Ken MacLeod for linking to my essays on Althusser and on the conflict between Leszek Kolakowski and EP Thompson.

I'm grateful to sci fi socialist Ken MacLeod for linking to my essays on Althusser and on the conflict between Leszek Kolakowski and EP Thompson. I had an exchange with Ken after taking umbrage with part of this post of his. Ken had posed an interesting question:

Who were the really influential Marxist intellectuals? I've never read more than a few pages of Marcuse or Althusser, or any of the famous 'Western Marxists', apart from (not enough) Gramsci and Lukacs. You know why? Because they're very difficult to read. Gramsci and Lukacs had excuses for obscurity. The rest didn't.

No, the really influential Marxist intellectuals are those wrote well and clearly. They weren't philosophers or Critical Theorists but historians and economists - and Trotsky. A lot of Trotsky's influence can be attributed quite simply to the fact that he couldn't write a dull page. It was Trotsky's History of the Russian Revolution that first interested Paul Sweezy in Marxism; likewise C.L.R. James, who went on to write one of the greatest Marxist histories, The Black Jacobins. (Not a dull page, and not a careless or undocumented word.) Paul A. Baran was a pupil of the Left Opposition economist Preobrazhensky, another lucid writer. (It's just struck me that Preobrazhensky might be a key to the whole Monthly Review school. Hmm.)

When you add up the influence of Paul Sweezy, Paul A. Baran, Leo Huberman, Harry Magdoff, Maurice Dobb, Ernest Mandel; Isaac Deutscher's biographies; C.L.R. James, Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, and, yes, E.P. Thompson; Gordon Childe; J.B.S. Haldane and J. Bernal - you've gone a long way to account for the intellectual influence of Marxism in at least the English-reading world. All of them wrote for readers who weren't Marxists. And non-Marxist, indeed anti-Marxist, readers have profited from their work ever since. Some who weren't Marxists when they opened a book by any of these guys were at least half-way to being Marxists when they closed it. Who ever became a Marxist as a result of reading Althusser?

Here was my typically intemperate reply to Ken:

Althusser's writing can be difficult, and is sometimes best approached through other people's summaries, but his ideas blew the minds of a lot of people who had thought that Marxism meant either starry-eyed but visions of socialist utopia or a plodding mechanical materialism. He showed that Marxism could be rigorous without being teleological and determinist.

And am I the only the one who finds this 'don't make things too difficult for the proles' talk a little patronising? If you applied MacLeod's difficulty test to the works of Marx himself, how much could you endorse? Certainly not large tracts of Capital. And yet the history of British working class self-education in Marx, as described in Jonathan Rees' Proletarian Philosophers, shows that generations of workers who had not had extensive formal education devoured some of Marx's most difficult works.

The 'this is too difficult' stuff seems to come from British intellectuals from a different class background, and that isn't surprising, because British academic thought is notoriously anti-philosophical and anti-theoretical.

I was probably shooting off blanks as usual, because Ken's reply shows that he doesn't pull any punches when it comes to Marxist theory:

I'm sorry that anyone should get the impression that my point is 'don't make things too difficult for the proles'. OK, I called the writing of the Western Marxists 'difficult' but in context it's clear that what I'm objecting to is their wilful obscurity, as distinct from the wily obscurity of Gramsci and Lukacs, as well as to the clarity of the most difficult passages of Capital. In Perry Anderson's Considerations on Western Marxism there's a famous page in which he makes the same contrast in his own inimitable way, to the point almost of self-parody.

I've noticed that whenever I've criticised the 'Western Marxists' for their wilful obscurity, the comeback is always this is philistine and patronising. How it can be philistine and patronising to recommend reading the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin, as well as those who (in my view) continued their work of investigating social reality with a view to changing it, is never explained.

I think it's reasonable to criticise Althusser and many of his followers - this bunch are a particularly egregious example - for being unnecessarily obscure. I think it was Wittgenstein, who was often guilty of not following his own advice, who said that 'The time you save in writing your text by not making it as clear as possible, the reader has to make up on your behalf'.

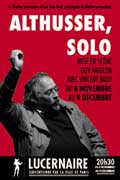

All the same, I am a little baffled by the latest sneer at poor old Louis on British lefty journo Dave Osler's blog. Dave is amused by the news that those wacky Parisians are putting on a play based on Althusser's autobiography:

Anyone who has read Althusser’s books – and I tried, I really really tried, but the man's work makes Jurgen Habermas read like chick lit – will realise that this is an unlikely basis for gripping contemporary theatre.

I wonder how hard Dave tried to read The Future Lasts a Long Time, which is the English translation of the autobiography that was published soon after the great man's death in 1990. Imprisonment in a POW camp, a semi-underground life in the French Communist Party in the years after the war, endless erotic adventures, a murder in mysterious circumstances, a plot to steal a nuclear submarine, an attempt by de Gaulle to pick Louis up in a Paris backstreet: what more dramatic interest could the desperately sad yet wildly funny story of Althusser's life possibly need? Hell, The Future Lasts a Long Time is the only Marxist book that Jack Ross raves about. Get down to your local library, Dave...

11 Comments:

But, which, if any, of Althusser's ideas, as distinct from ideas that he takes from Marx or Gramsci et al., survive as part of the essential Marxist corpus?

Do any of Althusser's ideas rate alongside those of Trotsky, say, 'combined and uneven development'- where the articulation of modes is already theorised; permanent revolution - did Althusser's structural theory ever approach the level of many determinations that allowed him to talk about 'real life'?; fascism and the popular front - (did Althusser ever break with the French CP on these questions?) and so on.

Couldn’t post this at Davd Osler, so here’s my reply to your comments there.

Scott wrote:

you are not engaging with them in a comradely spirit.

Firstly, you might take that point up with Snowball, SWP's pet historian, who has fine comradely debating skill, as shown above.

You're absolutely correct the comradely spirit is the best way, but sadly that has been tried by people considerably more lucid than I, Mike Rix and Mike Marqusee

see http://www.labournet.net/other/0308/marques1.html

http://libsoc.blogspot.com/2003_08_10_libsoc_archive.html and

http://www.whatnextjournal.co.uk/Pages//////Politics/Mickrix.html

Now, I don't know your politics, but I find hard to work with people who think killing Iraqi trade unionists is unacceptable practice as the leaders of the StWC seem to think.

Equally, I would find it hard to work with people who shout "we are all Hezbollah" and lionise Hassan Nasrallah, I know that is very judgemental and I should suppress my urge to say these people are quasi-fascist thugs and anathema to everything remotely socialist.

By the same token I should suppress my utter loathing for George Galloway, his political antics, his support for Middle Eastern dictators, etc but I can't .

I have a particular loathing for fascists, quasi-fascists, reactionaries, etc, their lickspittles and people that pander to them, that is my issue.

Of course, some 25-30 years ago when I ran across solid SWP trade unionists I might have warned them about associating with Islamists, sucking in their policies, suppressing anything remotely socialist or secular and certainly not bringing up women's or gay right, but particular these trade unionists wouldn't need to be told that that is not what socialists do: make alliances with Islamists and reactionaries. Then again I would suspect that those solid SWP trade unionists no longer associate with the SWP, they’d know better.

I'm not sure if you're familiar with the "antiwar" movement in Britain?

At one point, it was extremely large, now it is a pale shadow of its former self, dominated by the SWP: organisationally, tactically and politically, so the room for "comradely" debate is about as wide as a fly’s wings.

The SWP leadership have used their prerogative of democratic centralism to tell people what to think, and a lot of people have gone along with it. Here's the rub, 100,000s of 100,000s (in Lefty lingo known the masses) have simply decided with their feet, they have walked away from the shenanigans and political manipulation enacted by the SWP in the antiwar movement

Why did they walk away? I'm not sure, I personally found the whiff of antisemitism a bit too much for my nostrils, also as an atheist I grew sick of that extreme pandering to “religion” that went on (I suppose they did it, in the hope that the SWP would recruit some bodies?).

Now, of course, you can call everyone that walked away from the SWP controlled stop the war coalition a "counterrevolutionary" or "imperialist" etc but it doesn't matter, that's what people have done.

I suspect a percentage of them walked away from the StWC, when they realised it wasn't antiwar, it was pro-war (just the other side) and a recruitment vehicle for the SWP.

Those are the facts on the ground, and if you can find a moderately intelligent SWPer who can explain rationally (without parroting his central committees' utterances) how the antiwar movement in Britain went from millions and millions to some 100,000 max, I’d welcome a summary.

Basically they had it in the palm of the hand and they fucked it up completely, but they did it consciously and continue to do.

So my comradely tone reflects that :)

I think Slog is essentially right - what was althusser's distinct contribution? - apart from perhaps introducing a tighter structuralist straightjacket.

Although I agree that difficult things shouldn't be rejected on the sole basis that they are difficult - it doesn't imply (and I'm not saying you're trying to do this) that all things that are difficult to engage with are worth engaging with.

Academic Marxism has always been, in my view, its weakest point. Gramsci's writings before prison are pretty straight forward and easy to understand because he was an active revolutionary writing for workers.

I think academics exclusively read Gramsci's prison writings because the ambuigity and jargon allow them to forget what praxis really means in favour of (incorrectly)labelling themselves organic intelluals.

Actually that might be a bit harsh.

But, guys, Althusser was a *philosopher*, not a historian or sociologist. Philosophers do different work to social scientistS. If you go looking through Althusser's work for empirical studies of society or history of the sort that you'll find in EP Thompson or Trotsky then of course you'll be disappointed.

But the role of philosophy is not to coin substantive theories about society and history but to sharpen the conceptual tools that social scientists use. This is where Althusser's real contribution lies. Judging him against a social scientist is liking judging the Theses of Feuerbach against Capital. Different texts, different disciplines.

But what is a Marxists attitude to philosophy? As a subject seperated from society?

The concept of praxis is that ideas and action are inseperable.

Just as you can't divorce ideas from the society that produced them you cannot ignor the fact that philosophy either politically engages with the real world or its ideologically dead.

For the Marxist

To say that philosophy is a distinct intellectual activity, different from history or sociology or mathematics, is not to say it has to exist in splendid isolation from life.

Those who believe that Marx abolished the need for philosophy in the Theses in Feuerbach need to explain his subsequent philosophical writings, as well as works like Lenin's Philosophical Notebooks. I think one of the most important writers alive today is the philsopher Bertell Ollman:

http://www.nyu.edu/projects/ollman/index.php

I think Althusser's philosophical work was intended as part of a wider project which involved social scientists developing detailed concrete analyses of social reality and activists attempting to chnage that reality.

It's often forgotten that Althusser's work inspired a large amount of work by sociologists, economists, historians, and so on, and that it was also picked up and used by factions inside the Communist Party of France and the trade union movement, not to mention

groups outside France.

Having said that, there's no doubt Althusser's own political thinking and practice were frequently faulty and naive. But much the same could be said about the political practice of some of the greatest Marxist thinkers - Lukacs and EP Thompson are two who spring to mind.

Sorry, I meant that Ollman was one of 'the most important Marxist writers alive'...

But wasnt Althussers real claim to fame his discovery of the 'real' Marx - the 'scientist' and not the tame humanist philosopher. His evidence? The work of Capital.

So where is 'philosophy' in Capital? Its dissolved into the method of abstraction that us used to do the analysis of commodity-cells etc etc. laid out neatly in the intro to Grundrisse.

IMO Althusser resurrects 'philosophy' as an idealism that transcends and exists independently of the 'last instance' - the real world. In this last instance, his separation of levels of analysis serves his purpose of junking the superstructure of Stalinism (disown Stalin!) and rescuing the gains of the Russian revolution (whew).

Althusser gave academic marxism a bit of respectability against the 'new philosphy', but it was also the victim of the failed 1968 in its retreat into structuralism where never the objective and subjective are joined.

Where are all the Althusserians today? Poor Poulantzas made a quick exit because he followed the political logic to its bitter end - Eurocommunism. Hindess did the whole bit into Foucault. The rest are probably university adminstrators or in business.

Too bad big A never ran into Trotsky's ideas as a 'praxis' to run his philosophy over. Of course I blame the Trotskyists for that.

Philosophy can't be 'dissolved' into the method of abstraction anymore than it can be dissolved into the method of the syllogism. The method of abstraction can't be explained by its end product, anymore than the syllogism can be explained by its end product.

You can't read Marx's chapter on commodities, or Trotsky's analysis of fascism, or Lenin's theory of imperialism, and magically grasp the method which was used to generate these analyses. The method needs to explained, discussed, defended - and this is the discourse of philosophy. If philosophy could simply be 'dissolved' into Marxist social science, then Marx would never have indicated his desire to write a work on dialectics, Lenin would never have produced the Philosophical Notebooks, and Trotsky would never have written the ABC of Dialectics.

Anyone can say that Marx's work is scientific, or that there is a break between the early and late work. Althusser created a method - the immanent critique - which enables us to actually do something useful with such claims.

Likewise, anyone can protest that Marx's view of history is neither reductionist nor hopelessly vague. But Althusser was able to give us a concept - overdetermination - which

helped us make sense of this claim.

It is true that in his mid-60s work Althusser advances a conception of philosophy as 'the science of sciences' which is idealist. But he breaks with this conception in his later work - in 'Is it easy to be a Marxist in Philosophy?', for instance - to produce the first truly materialist account of what philosophy is.

There's been a revival of interest in Althusser in the last few years amongst younger scholars, but I doubt whether anyone would call themselves an 'Althusserian' these days. I think that Bertell Ollman is the best living Marxist philosopher, and the most cogent expositor of the dialectical Marxist method ever, but I wouldn't call myself an 'Ollmanian'.

I find Hindess, Hirst and the other 'English Althsserians' intolerably dull. I venture a sociological explanation for their strangeness at the end of 'The Eagle and the Bustard':

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.com/2006_07_01_readingthemaps_archive.html (if anyone is interested, you have to scroll down to find the post - don't know what's wrong with my search engine at the moment)

But wasnt Althussers real claim to fame his discovery of the 'real' Marx - the 'scientist' and not the tame humanist philosopher. His evidence? The work of Capital.

So where is 'philosophy' in Capital? Its dissolved into the method of abstraction that us used to do the analysis of commodity-cells etc etc. laid out neatly in the intro to Grundrisse.

IMO Althusser resurrects 'philosophy' as an idealism that transcends and exists independently of the 'last instance' - the real world. In this last instance, his separation of levels of analysis serves his purpose of junking the superstructure of Stalinism (disown Stalin!) and rescuing the gains of the Russian revolution (whew).

Althusser gave academic marxism a bit of respectability against the 'new philosphy', but it was also the victim of the failed 1968 in its retreat into structuralism where never the objective and subjective are joined.

Where are all the Althusserians today? Poor Poulantzas made a quick exit because he followed the political logic to its bitter end - Eurocommunism. Hindess did the whole bit into Foucault. The rest are probably university adminstrators or in business.

Too bad big A never ran into Trotsky's ideas as a 'praxis' to run his philosophy over. Of course I blame the Trotskyists for that.

This comment will probably dissolve up its own ass. Wrong word 'dissolve'. Should have said 'abolished'.

Ollman OK. But where does he say that Marx has a philosophy? I thought he talked about Marx's dialectical method.

Marx did write about dialectics, in his critique of Hegel. But in the German Ideology which settled accounts with the young Hegelians, 'philosopy' is ideology. (That would suit Big A whose definition of ideology conveniently included his own philsophy).

I don't know where or when Marx said he wanted to write about Dialectics.

If it was something he didnt get around to I imagine it would have been a primer in scientific method to rub the empiricists noses in, or to accompany the popular comic of Capital.

As for Lenin and Trotsky. I forget what Lenin finally said about philosophy. My impression was that he critiqued the history of philosophy but did not replace it by Marxism as a 'philosphy' but by dialectical materialism as a method.

Lukacs defines the materialist dialectic as a scientific method.

Trotsky in ABC defines dialectics as a "science". He only saw the need to explain the dialectic facing the crisis of the impending split in the SWP over the 'Russian question'. So dialectics is 'praxis' not philosophy.

The notion that Marx made philosophy redundant was actually created largely by Third Period Stalinism, not Marx or Lenin. I'll post on this properly when I have the time, but take a olook at lenin's late essay 'On the signifance of Militant Materialism', which argues that the study of Hegel and other 'bourgeois' philosophers is vital to the health of Marxism in the USSR. Such a claim of course recalls Lenin's famous comment in the Philosophical Notebooks that nobody who has not read Hegel's Logic can understand Capital:

http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1922/mar/12.htm

Post a Comment

<< Home