Before Parihaka

Like most boys of my generation, I was an ardent militarist. A steady diet of Battle Picture Weekly comics and Saturday afternoon repeats of World War Two black and whites fed my obsession, and birthdays brought new additions to my arsenal of plastic rifles, bows and arrows, boomerangs, and jungle knives. It's no surprise, then, that on visits to the Auckland Museum I gravitated towards the third floor, where the World Wars were commemorated in a series of huge rooms full of sacred objects: dented German helmets, rusty rifles, a jerry-built wireless with a wax operator, and a spitfire kept like a caged bird behind steel railings. The rooms were connected by a Hall of Remembrance, where flags of long-extinct nations hung listlessly from marble walls covered in the names of dead soldiers.

At the end of the hall, in what might have been a converted storeroom, a number of less sacred relics - a weatherbeaten chest, a musket with a strange bird carved on its shoulder, a Maori Bible - sat in glass cabinets too big for them. The room was lit as dimly as a cave, so that I had to squint to read the captions under the artifacts, the maps and pictures on the wall, and even the sign beside the door that said NEW ZEALAND WARS.

The wars commemorated by this room made no sense to me: here the Maori soldiers who had turned up occasionally in Battle Picture Weekly, doing war dances in the desert beside the wreckage of Rommel's tanks, were fighting against the side carrying the Union Jack. Worse, the two sides were fighting in ridiculous places, places like Rangiriri, the gas station on highway one where we'd stop for pies on the way to Rotorua, and Russell, a beach where I'd gone snorkelling while my brother lay in a nearby motel with mumps. There were no smoking Panzers or shell holes in Rangiriri or Russell.

There was one exhibit in the converted storeroom that did interest me. Placed between Te Kooti's chest and somebody else's Bible, it was a black and white drawing no larger than a postcard. A black pillar adorned with an upturned crescent moon and two pyramids rose out of a river; beside them, a large round sun had sprouted a human hand. The hand was waving - to say hello, or to warn the viewer away? Another hand could be seen below the sun, part of a forest of images that the drawing's small size made difficult to see in the dim light (looking at the drawing now, in clear light and with a head full of interpretative frameworks, I don't see the same images). I kneeled and squinted and read the caption at the bottom of the glass cabinet:

Reproduction of a drawing by Aporo, a Hauhau mystic, showing fantastic machinery and supernatural beings. As time went on Maori looked to supernatural forces to deliver them from the nightmare that the wars had created.

Who was Aporo? What was a Hauhau? That night, in the quarter hour between the end of Dukes of Hazard and bedtime, I took the Australasia volumes of the World Book Encyclopedia down from the lounge room bookshelf.

Hauhau, pronounced how-how, Maori religious sect opposed to colonisation, whose members believed they were magically protected from bullets. Hauhaus claimed that their gospel was spoken to them by the severed head of a British soldier. Their name came from the chant they used as they advanced into battle.

There was no entry for anyone called Aporo, and I didn't know where else to look. Every time we had a school trip to the museum, though, to look at an exhibition on New Zealand Native Birds or The Life of the Seashore or The Way Your Grandparents Lived, I would wait until my teacher's back was turned, and then steal away, up the echoing marble stairs and down the Hall of Remembrance, to the cave where Aporo's drawing waited in its cracked glass cabinet.

Years after finishing school, I encountered Aporo again, in section 211 of Atua Wera, Kendrick Smithyman's last, longest, and most baffling poem:

Gilbert Mair shot Rota Waitapu in a cave

under a waterfall near Whakamarama,

inland from Tauranga, 1867.

Rota, known as Aporo, was Hauhau.

From his body Mair took a packet,

nineteen sketches,

Aporo's dreams.

Smithyman describes some of the drawings:

One dream: points of compass as cross.

To the left, Man (Moses?) holds a staff (with leaves?).

Up that staff climbs (or is the staff climbing into?)

a serpent?

Another dream:

Left margin, a hill turned so the hilltop is to

the centre of the drawing...

Bottom margin, a hill.

From the hilltop

Man's head protrudes; this is the head of

the body of the land?

This is the body which is

tenanted by lizard-like creature. It has

perhaps four sets of legs. The extreme tail curls

round Man's head. Man looks up,

to, diagonal, rising from left low to high right,

another lizard-like creature with four pairs

of legs, a fifth pair more arms than legs.

One pair of eyes, but the head, heavily blacked,

is in double (beaked?) profile.

No question about it being a monster.

By now I knew where to look for more details about Aporo's death: I'd been using James Cowan's two volume history of The New Zealand Wars to explore battle sites in the Franklin County and lower Waikato areas. Written in the 1920s in a flowery, rather fin de siecle prose style, and punctuated with sincere but patronising references to the 'decline of the noble Maori race', Cowan's magnum opus frequently blurs the boundary between scholarship and obsession. Cowan's narrative of the guerrilla fighting that accompanied the building of the Great South Road through south Auckland had led me to a windy churchyard on a hill near Pukekohe, where a party had Maori had staged a disastrous attack on a small group of well-armed settlers one hundred and forty years before. The Maori had failed to kill a single defender of the little Presbyterian church, but they had left a dent in one of the gravestones in the yard. Cowan provides a map showing the location of the church, a map of the churchyard showing the location of the stone, and a map of the stone itself, showing the location of the shallow indentation a musket shell had left.

Cowan's narrative of Aporo's death is as detailed as one might expect:

In the early part of 1867 the tribe called Piri-Rakau (“Cling to the Forest”), descended from ancient aboriginal clans, came into conflict with the Government forces in a series of sharp skirmishes along the northern edge of the bush-covered tableland in rear of Tauranga Harbour. These Piri-Rakau, assisted by parties of men from other districts, were all Hauhaus...

In the middle of February a strong expedition was organized at Tauranga to attack Te Irihanga and Whakamarama again. On this occasion the force was composed almost entirely of Arawa natives commanded by Major William Mair and his brother Gilbert. Captain H. L. Skeet's company of volunteer engineers, a fine body of young surveyors, all well accustomed to bushwork formed part of the column, and several companies of the 1st Waikato Militia acted as supports...

The retreating enemy were pursued through the belt of forest, about a quarter of a mile in length, separating Irihanga from the eastern end of the Whakamarama village and fields...Their resistance was broken by Harete te Whanarere, one of a famous fighting family of Ngati-Pikiao, from Rotoiti. On the side of the track, where the huge, densely foliaged trees make a twilight gloom, he pluckily grappled the foremost of the antagonists, a big Hauhau, whom he threw to the ground. The two warriors were engaged in a desperate struggle when another Hauhau dashed out from his cover, and, placing the muzzle of his Tower musket against Harete's body, fired and smashed both the hip-joints. (Though terribly wounded, Harete survived for some years.) Hemana then dashed up and killed the man who had shot Harete. Several of the Piri-Rakau were wounded in the tree-to-tree fighting here. It was typical bush warfare for a few minutes. Only the black heads of the combatants were to be seen now and again, and the muzzle of a gun showing for an instant, followed by a puff of smoke, then an instant dash for another tree. The Hauhaus presently broke and fell back on their main body at the Whakamarama village.

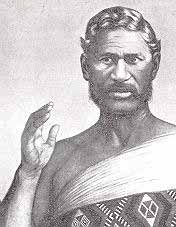

Just after the Piri-Rakau had retreated from the scene of this skirmish midway through the belt of bush Ensign Mair noticed a trail of blood leading down to a deep gorge on the left, or east, in the direction of Poripori. There was a faint track here through the forest to Poripori, which the Piri-Rakau had marked by breaking and doubling over the fronds of the fern called tu-taumata (Lomaria discolor), which are silvery-white underneath. When doubled over, the white under-surface of the fern showed conspicuously against the dark green of the ferns, moss, and tree-trunks around it. Mair observed that these white fronds were splashed with blood; and, diverging from the route followed by the others, he scouted down to the creek in the gorge. Hot on the trail, he followed the blood-marks to a cave, over the mouth of which a little waterfall came down. A shot rang out from the cave, narrowly missing him. Mair rushed in and encountered a wounded Maori kneeling behind the rocks in the gloom, and shot the man dead just as he was levelling his long single-barrel gun for another shot. Taking the dead warrior's gun and whakakai pendant of tangiwai greenstone as trophies, Mair hurried back to the scene of the fight. He found by inquiry afterwards that the man he had shot, a big tattooed warrior, was a Piri-Rakau named Rota, one of the leading men of the turbulent tribe.

Disappointingly, though, Cowan showed no interest in Aporo's drawings. I looked through university library catalogues and on the internet for reproductions of the originals, which are housed in the Special Collections of the Turnbull library in Wellington, and eventually tracked some down in the appendix to an occasional paper written by Waikato University's Evelyn Stokes. Stokes' paper, which is probably held in no more than half a dozen libraries around the country, was published by a photocopier in 1980. Even blurred around the edges on cheap smelly paper, though, Aporo's vision is astonishing. Like some Maori Blake, he mixes the visionary and the everyday, high drama and low comedy, thunderous denunciation and sly humour. His style is at once childlike and sophisticated: forsaking the abstract, highly formalised tradition associated with Maori meeting house art and carving, he appropriates the realism of European sketchers and cartoonists. Some of the drawings were given gnomic, ominous captions:

In my darkness and distress I slept and I dreamed I saw this sign, the form of a red cloud in the sky, a flock of small birds and a large one in their midst, all gathering around the great cloud where they settled with their large friend. Then I awoke.

The break with tradition in Aporo's drawings reminds us of the paintings in the meeting houses Te Kooti's Ringatu movement built in the 1870s and '80s. The Ringatu paintings were regarded as an embarrassment by the patronising Pakeha who founded the Maori School of Art in Rotorua in the 1920s, and for decades ordered their charges to turn out pastiches of pre-contact carvings to sell to tourists. The genius of Ringatu painting was only recognised by Pakeha art historians in 1993, when Roger Neish published his monumental study Painted Histories. Why do Aporo's drawings still await such acclaim? Part of the answer to this question lies in the worldview they express so powerfully.

Aporo was a follower of Te Ua Haumene, who was a prophet from the Ngati Ruanui tribe of Taranaki. Taken prisoner as a child and raised as a slave in the Tainui stronghold of Kawhia, Te Ua occupied only a lowly place in Ngati Ruanui society after returning home. In 1862, though, he experienced a series of visions in which the archangel Gabriel visited him and explained that he was the anointed prophet of God, and that the last days of the world were at hand.

Te Ua's visions came amidst a crisis in Ngati Ruanui society. A British-owned ship called The Worsley had run aground off the coast of their territory, on the wrong side of the aukati or boundary beyond which Europeans were not allowed to venture. As the tribe debated whether or not to punish the survivors of the wreck, Te Ua found himself torn between his hostility to colonialism and his Christian belief in non-violence. The tension between the two was resolved by Gabriel, who offered a new route to peace:

Te Ua's visions came amidst a crisis in Ngati Ruanui society. A British-owned ship called The Worsley had run aground off the coast of their territory, on the wrong side of the aukati or boundary beyond which Europeans were not allowed to venture. As the tribe debated whether or not to punish the survivors of the wreck, Te Ua found himself torn between his hostility to colonialism and his Christian belief in non-violence. The tension between the two was resolved by Gabriel, who offered a new route to peace:This is a word for the ministers, for Whiteley, Scott and Brown, for every minister living in the island. Let them go back to the other side of the sea in Goodness and Peace, go back to Goodness and Peace, because peaceable God has told me twice that his people, Forgetful, Standing Naked, in the Island of Two Halves will be restored, even to that which was given to Abraham, for this is Israel.

Those words and the rest of Gabriel’s message were recorded by Te Ua in the beautiful, sometimes baffling texts he called ‘Ua Gospel’ and 'Ua Rongopai'. Some passages in the texts read like a strange sort of poetry:

For which is [God’s] aspect on Taranaki mountain? Which is it? White? Black? It is as the whiteness of paper, when it is written on by Hemi Kaka[hi] Tohu and te Ao Katoa. And, which is his aspect while the natural man is sleeping? Calm and shining. That is the Ace of Spades, Maori Woman. She is Gleaming Night.

But you are saying, I am drunk. To me, whose food is the spirits I consume? The natural man must eat. Man will err; thus Natural Man shall eat in fitting moderation.

Some of the words of Te Ua’s gospels were reputed to have been channeled from Gabriel through the mouth of Captain Thomas Lloyd, who had been beheaded after leading six soldiers into Ngati Ruanui territory on a crop-destroying mission. Lloyd's head was allegedly carried across the North Island to the western Bay of Plenty, the home of Aporo's tribe, so that Te Ua’s message might be heard.

By the middle of 1863 Te Ua's religion, which had become known as Pai Marire (the good and the peaceful), had gained converts across much of the North Island. Eschewing traditional churches, the faithful erected niu poles modelled on the mast that Ngati Ruanui had salvaged from the wreck of The Worsley. They would circle the pole, reciting prayers and chanting. The doctrine of Pai Marire was syncretic and flexible, mixing Maori nationalism and Christian apocalypticism, and its founder soon lost control over its adherants. A year after Te Ua died of tuberculosis in 1864, his creed became a byword amongst Europeans for brutality and barbarism. At Opotiki, in the eastern Bay of Plenty, followers of Pai Marire fell upon the local missionary, who was suspected of spying for the government, in the church that he had built. Carl Volkner's eyes were ripped out of his head, and his blood was drunk from a communion cup. Writing one hundred and thirty years after the slaying of Volkner, L Head reflected that:

This was the single event which defined the character of Te Ua and his faith for 100 years. The death outraged the values of Pakeha, to whom the mission culture was a necessary sign of their own meaning in a silent land…As a prophet, Te Ua preached deliverance, whose corollary was the destruction of the unrighteousness. In this sphere of the spirit, pacifism is an irrelevant concept.

The violence of the 'Hauhaus' only seems an inexplicable explosion of barbarism when it is lifted out of its historical context. Kereopa Te Rau, the ringleader of the group that killed Volkner, had lost his wife and daughter when British troops burnt a church full of cowering civilians to the ground at Rangiaowhia, in the last days of the Waikato War. Marx might have been discussing Volkner's killers when he wrote about the Indian Mutiny a few years earlier:

The outrages committed by the revolted Sepoys in India are indeed appalling, hideous, ineffable — such as one is prepared to meet – only in wars of insurrection, of nationalities, of races, and above all of religion…

However infamous the conduct of the Sepoys, it is only the reflex, in a concentrated form, of England’s own conduct in India, not only during the epoch of the foundation of her Eastern Empire, but even during the last ten years of a long-settled rule.

It is instructive to compare the posthumous fates of Te Ua and a later Taranaki prophet, Te Whiti. Today most New Zealanders know the story of Parihaka, the nation that Te Whiti and his followers founded in south Taranaki on pacifist and communitarian principles. Using 'the miracle of collective labour', Parihaka's inhabitants established extensive and rich cultivations; their capital prospered, and boasted electricity and street lamps before the Pakeha capital of Wellington. In 1881, though, an armed party sent from Wellington entered Parihaka and supressed Te Whiti's separatist movement. The inhabitants of the area waged a campaign of civil disobedience in an ultimately fruitless attempt to prevent the theft of much of their land by colonists.

Since the publication of Dick Scott's Ask that Mountain, Te Whiti has been an icon for liberal Pakeha. A recent book called Parihaka: the Art of Passive Resistancecollected scores of images and texts that paid homage. Te Whiti's pacifist teachings and the community he founded are commemorated in a Peace Festival held every year at the small settlement that remains at Parihaka.

The differences between the teachings of Te Whiti and Te Ua can partly be explained by the different historical contexts in which the two prophets operated. Te Ua founded Pai Marire at a time when European control of Aotearoa was still more an assertion than a reality, and an independent Maori nation stretched from the outskirts of Auckland well into Taranaki. Te Whiti, by contrast, came to prominence in the aftermath of the New Zealand Wars, when the hegemony of the government in Wellington over virtually all of Aotearoa was unquestioned. Parihaka was squeezed between expanding Pakeha settlements, and was always doomed to incorporation into New Zealand. Te Whiti's pacifism may have been noble, but it was probably also a necessity. The option of armed struggle was no longer open, and with most Maori living in remote rural areas there was little prospect of striking up a workable alliance with progressive parts of Pakeha society.

Te Whiti's liberal followers, though, convert necessity into a dogma, and assimilate the brutal termination of the nation of Parihaka into a cosy myth of New Zealand nationhood. Here is an excerpt from the publicity for the Parihaka International Peace Festival:

The authorities responded to Te Whiti and Tohu by ransacking Parihaka and arresting many of the residents. However, the incredible publicity generated by the non-violent movement shattered the propaganda purporting the indigenous Maori people to be ‘heathen savages’ and started a turn around in recognition of Maori rights and the development of a just and peaceful nation.

One hundred and twenty-six years after the destruction of Parihaka, the 'just and peaceful nation' of New Zealand routinely uses Maori troops and police to occupy modern-day Parihakas - the Solomons, East Timor, Afghanistan, Tonga - in the interests of the world's leading imperialist power, which is nowadays the United States rather than Britain. In the Solomons, our troops and cops have helped provide the muscle for a neo-colonial administration that has made one of its priorities the destruction of laws that protect indigenous ownership of land. In Afghanistan, the forces of our 'just and peaceful nation' are helping destroy the main crop of the indigenous people, just as the force Wellington sent to Taranaki in 1881 destroyed the cultivations that sustained Parihaka.

Pakeha liberals like to compare Te Whiti to Mahatma Gandhi, and the comparison is in some ways apt. In Richard Attenborough's absurd 1982 biopic Gandhi is cast as a saintly figure who won independence for India with passive resistance and prayer. The real, messy history of the Indian struggle against imperialism, with its armed revolts, massacres of British civilians, wartime alliance with Japan, and communist-led strikes is effortlessly ignored by Attenborough. In much the same way, Pakeha liberals focus on Te Whiti, who was a heroic but relatively minor figure in the struggle against colonisation, at the expense of those like Tawhiao, Te Kooti, and Titokowaru who used armed struggle against the British and the settlers.

Aporo and Te Ua are not as easily celebrated by liberalism as Gandhi or Te Whiti. Aporo's Book of Dreams and Te Ua's gospels are complex, confrontational works that fuse apocalyptic religious visions with nationalist politics, and exhibit an anger and pain very different from the beatific quietism associated nowadays with Te Whiti. It is time that the Pakeha who have celebrated Te Whiti and Parihaka also recognised the extraordinary legacies of these two earlier opponents of imperialism.

Footnote: some of Aporo's drawings are now online here.

For Te Ua's texts with an English translation and commentary, see 'The gospel of Te Ua Haumene', Journal of the Polynesian Society 101:11, 7-44, Polynesian Society, 1992

10 Comments:

Enjoyed your post.

Liberals don't like to remember that Te Whiti had fought in the early days of the war around Waitara but after having his pas destroyed retreated to Parihaka, which became a retreat for Waikato Maori after the Waikato wars and for fighters like Wirimu Kingi from Waitara and Titokowaru himself. His pacifism was really self-preservation.

It would gall the liberals who fete Te Whiti today to know that he had their number. If he was hosting the Peace Huis he would no doubt demand they leave their money behind, foreswear their private property and join the work gangs to produce their keep, and then on venturing back into the world of evil, plough their own fields.

This is a great post Scott (Maps) - fascinating how old Smithy got there first (so to speak) - he was onto things! Not called the sly old fox of NZ Poetry for nothing!

I see a lot of Te Atua Wera is online - I had the book but someone lost if for me ... (no one's fault)

Yes - Parihaka was a great event - but all of us "liberals" or others do wrong to simplify the struggle between Pakeha and Maori in the process of Colonialisation in which great and many injustices occurred.

But it was not a simple - good guy bad guy sitation -we can see the prcocess of divide and rulse used by the pakeha invadors as the US are using the Israelis and various Moslem groups to do their dirty work or to fight amongst themselves in the attempt by the British and US Imperialists to keep control or just keep war going while (the Big Capitalists) suck out oil and drugs.

The success of the Indian struggle for Independence has - as you say - been too much talked of as being facilitated or brought about only by pacifism and Ghandi et al - as with the Chinese struggle for independence (against the Japanese etc) - there was much war and voilent indeed very bloody struggle.

An old friend (sadly now not alive) of mine was in the British army in India, and preiviosly in other places and also in hte Second World War he was in Germany and sometimes in North Africa - and he broke down a the time of the My Lai massacre as it reminded him too much of his experiences in India - he had joined the British army in Glasgow as young man (no other work or not much) and had become a Sergeant - but he also was vastly read and used facilities in the army to teach himself Marxism and history etc - he told me how he and others were ordered to take his men against the Indians on "search and destroy missions" - these could be interpeted how he liked (hence there were quite a few My Lais in India before the Liberation of that nation from the British).

This brutal side of British Imperialism is elided too much.

This is how Imperialism becomes fascism - it was heading that way in NZ and it hapenned in India China and many other places and Vietnam and Korea - and it is hapenning now in Iraq. (But those countries wern't overwhelmed by mumbers and they all eventually won - and the Iarqis and others will eventually push out or destroy the Israelis and the US etc).

Armed struggle in such circumstances is necessary. Pacifism is useless - except when one is beaten.

Great the connections you find. Smithy's big poem is subversive (and thus and because) - informative.

Your post reminded me that I ahd somehow collected "The Story of Gate Pa" by Captain Gilbert Mair (unread - must do so) and The Stirring Times of Te Ruaparaha and The Sacking of Kaiapohia" both unread - my scandalous neglect in this area of study. Must correct this.

Hauhau is not pronounced 'how-how'.

A closer aproximation would be the English word 'hoe'(x 2).

Your analysis here is much less reductive and patronising than it tended to be at other times.

I remember that when they did their book of poems and images about Te Kooti, Wystan Curnow and Leigh Davis got criticised by Tina Schwarzkauf-Paul for rhyming

'Hauhau' with 'Mau Mau'.

'Your analysis here is much less reductive and patronising than it tended to be at other times.'

Thanks, but which other times were you referring to? I've been critical for a long time of the (mis)use of Marxist categories to write off the history of indigenous peoples. For instance:

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.com/2006/09/karl-kautsky-vs-neanderthal-man-or.html

I'm just an amateur when it comes to Maori history - one day I'd like to learn the language and do some proper scholarship.

This "reductive" and patronising" stuff is just hogwash from some one with a sore head.

This comment has been removed by the author.

I think you got excellent memories having experiences like those, I'd like to living those experiences because when I living I can't belong to military group.m10m

he room was lit as dimly as a cave, so that I had to squint to read the captions under the artifacts,in clear light and with a head full of interpretative frameworks.

I am a private loan lender which have all take to be a genuine lender i give out the best loan to my client at a very convenient rate.The interest rate of this loan is 3%.i give out loan to public and private individuals.the maximum amount i give out in this loan is $1,000,000.00 USD why the minimum amount i give out is 5000.for more information

Your Full Details:

Full Name :………

Country :………….

state:………….

Sex :………….

Address............

Tel :………….

Occupation :……..

Amount Required :…………

Purpose of the Loan :……..

Loan Duration :…………

Phone Number :………

Mobile Number: +919910768937

Contact Email osmanloanserves@gmail.com

แทงบอลออนไลน์ สโบเบท เว็บไซส์เดิมพันออนไลน์ที่มีความนิยมติดอันดับของทวีปเอเชีย ที่สามารถเดิมพันได้ตลอด 24 ชั่วโมง และยังเพิ่มความสนุกไปกับเกมการพนันได้อีกมากมาย

Post a Comment

<< Home