This is another draft chapter from my PhD thesis on

EP Thompson. It's supposed to go near the beginning, because it describes Edward Palmer's family and some of the important events of his youth. I've got nearly all of my thesis in draft now, and am getting into what some people ominously call 'the really interesting stage' - that it, the period when you realise how little sense the chapters make when they are read alongside each other...

The Making of EP Thompson: family, anti-fascism, and the thirtiesEP Thompson is best known as the author of the

Making of the English Working Class, one of the great feats of twentieth century historical scholarship. In the

Making and a string of related ‘histories from below’, Thompson explores the lives of ordinary people in eighteenth and nineteenth century England with such finesse and sympathy that many of his readers assume that he had deep family roots in the world’s first working class. In truth, Thompson grew up in a comfortable suburb of Oxford.

Yet EP Thompson’s roots are not irrelevant to his life and writing. His family and the milieux it moved in gave him sympathies and interests that he would retain all his life. It may not be going too far to say that the lives and thoughts of Thompson’s father and brother, in particular, constitute a sort of preface to works like the

Making of the English Working Class. There is a continuity, if not a simple identity, between the lives and opinions of the three men.

To Bethnal Green and BankuraEdward John Thompson was born in 1886, the eldest son of Reverend John Moses, who had served as a Methodist missionary in India for many years before returning to England. A period of financial difficulties followed John Moses’ early death, and it was Edward John who was compelled to sacrifice his ambitions for the sake of his mother and his siblings. Despite winning a university scholarship, he left the Methodist-run Kingswood School to work as a clerk in a bank in the East End of London. After six unhappy years in Bethnal Green, the sensitive young man escaped to the University of London, with the understanding that he would secure a Bachelor of Arts degree before following in his father’s footsteps and entering the Methodist missionary service.

In 1910 Edward John arrived at the Methodist-run Bankura College in West Bengal. Bankura was a secondary school which would acquire a small tertiary wing, an outlier of the University of Calcutta, in 1920. The years Edward spent in India were a mixture of professional frustration and personal growth. Work at Bankura often seemed no more satisfying than work at the bank in Bethnal Green. With its emphasis on rote-learning and inappropriate, Anglophilic curricula, the college struck him as little more than a factory. Edward John felt that he was unable to pass on his love of literature and history to many of his students, and he doubted both the wisdom and effectiveness of the attempts of the school authorities to proselytise amongst their largely Hindu charges. In a letter he sent to his mother in 1913, Edward John commented wryly on the difficulties of bringing the word of God to heathens:

[O]ne boy said that at the Transfiguration Jesus had four heads…At the Temptation, ‘Shaytan was sent by God to examine the Jesus…and gave him his power. By the power of Satan he was able to [sic] many wonderful acts.’ Jesus wept over Jerusalem, and said ‘how often I would I have gathered thy children together, as a cat gathereth her chickens’. Despite or because of his frustrations, the young teacher quickly began a study of Indian society and culture that would last the rest of his life, spawn a dozen books, and make him one of Britain’s most respected authorities on the subcontinent. In 1913, Thompson made a visit to Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali writer and educationalist who had just won the Nobel Prize for literature. Thompson, who was himself a fledgling poet, soon began to translate Tagore’s poems and stories. Tagore encouraged Thompson to translate his poems and stories, and to persist with his studies of Indian and Bengali culture. By 1913 Thompson had become fluent in Bengali; he would eventually master Sanskrit, too.

In

Alien Homage, his study of his father’s relationship with Tagore, EP Thompson would suggest, with typical hyperbole, that by 1913 ‘the missionary was beginning a conversion of some sort by heathen legend, folklore and poetry’. It is probably more reasonable to say that Edward John had begun to consider himself a sort of bridge between Indian and English culture.

It is clear that Thompson quickly lost whatever sympathy he had ever had for the Methodist vision of an Anglicised, Christian India. He did not, however, simply turn his back on British and Christian culture. Instead, he had come to believe that India and Britain could complement and enrich each other. Elsewhere in

Alien Homage, EP Thompson describes his father’s contradictions with more subtlety:

It proves to be less easy than one might suppose to type Edward [John] Thompson when he first met Tagore. His association with the Wesleyan Connexion was uneasy…His distaste for the introverted European community at Bankura made him eager to seek refreshment of the spirit in Bengali cultural circles, where he was even more of an outsider who sometimes misread the signals. But even if he was not fully accepted on any of the recognised circuits, he constructed an unorthodox circuit of his own…He was a marginal man, a courier between cultures who wore the authorised livery of neither.

Thompson’s attitude may have been enlightened, by the standards of the Methodist missionary service in the second decade of the twentieth century, but it was by no means radical. An appreciation of some aspects of Indian culture did not imply opposition to the domination of Indian society by Britain. The bridge the young Thompson wanted to build would connect an imperial Britain with a political outpost of the empire. Robert Gregg has described limits of Edward John’s enterprise:

Thompson certainly did attempt to cross boundaries and make ‘homages’ to Indians and Indian culture that relatively few Britons at the time were making…in doing so he nevertheless replicated imperial models…he was a great believer in the imperial system… An aside about British intellectualsEdward John Thompson’s optimistic liberal imperialism was hardly exceptional in the generation of British intellectuals to which he belonged. The decidedly non-revolutionary behaviour of British intellectuals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has often been remarked upon by historians and sociologists, because it seems so contrary to the mood amongst the intelligentsia of other key European countries during the same period. Russia’s intelligentsia was notorious for producing rebels and critics of society. In France, the Dreyfus affair brought intellectuals together against the government and majority opinion.

In France, Germany, and to an extent Russia, intellectuals formed their own institutions, which played an important role in public political red debate, as well as in internecine academic struggles. It is little wonder, then, that the failure of the intelligentsia to develop the institutions and self-consciousness worthy of a distinct strata of British society in the nineteenth century has also raised eyebrows amongst scholars.

To understand the oddities of the British intelligentsia, we need to understand other peculiarities of British society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The modern British intelligentsia began to take shape in the mid-nineteenth century. Its emergence was encouraged by the growth of the British empire and state, the expansion of the reading public, and controversy over the nature of the university system.

The intelligentsia drew most of its members from the middle class professions and from the prosperous petty bourgeoisie. Many of its members had nonconformist and Evangelical backgrounds. The ‘reforming’ wing of the aristocracy was represented. Intermarriage and patronage eventually led to the emergence of what Noel Annan has called an ‘intellectual aristocracy’.

Conflict provided the stimuli for the emergence of a modern British intelligentsia. The British state grew to control the consequences of industrialisation. The foreign service grew as inter-imperialist rivalry led Britain to take direct political control of the territories it exploited economically. The debate over the role of universities was prompted by challenges to the exclusion of non-Anglicans from Oxbridge, challenges which were part of a wider call for the reform of the British elite’s institutions by an emergent industrial capitalist class .

British capitalism was stronger than its rivals throughout the nineteenth century. British pre-eminence helped limit social and cultural conflict in British society, and is ultimately responsible for the peculiar nature of the nineteenth century British intelligentsia. To get a sense of this peculiarity, we should note the situation of the intelligentsia in several other European countries.

The British intelligentsia did not enjoy a great deal of institutional and cultural autonomy – it was informally integrated with the country’s political and economic elites. The elite of the intelligentsia enjoyed an ‘Old Boys’-style relationship with the British ruling class. Old school ties, friendship and marriage were more important integrating devices than ‘public’ institutions with more or less meritocratic criteria for membership. Dissident fringes excepted, the British intelligentsia was not culturally alienated from its ruling class.

This ‘informal integration’ had its political corollary in a ‘high liberalism’ which was characterised by a belief in the progressive nature or progressive potential of British capitalism and imperialism. Economic dynamism and social cohesion made gradual social improvements possible. Intellectual influence was a matter of a word in the right ear of the elite, not a manifesto.

Noel Annan summed up the peculiarities of the English intelligentsia:

Stability is not a quality usually associated with an intelligentsia, a term which, Russian in origin, suggests the shifting, shiftless members of revolutionary or literary cliques who have cut themselves adrift from the moorings of family. Yet the English intelligentsia, wedded to gradual reform of accepted institutions and able to move between the worlds of speculation and principle, was stable.

Sheets of flameWhen World War One suddenly broke out in August 1914, Edward John Thompson’s optimism and patriotism were not at first affected. Like so many young Europeans, he felt stirred to ‘do his bit’ to help his country’s war effort. It was not until 1916, though, that he was able to become a chaplain in the British army. He spent time in Bombay, working with the wounded in the huge army hospital there, before shipping out for Mesopotamia, where British forces were engaged in a series of campaigns against the disintegrating Ottoman Empire. Moving up the Tigris River from Basra, Thompson’s unit was caught up in some heavy fighting. Thompson’s courage under fire earned him a Military Cross. After Mesopotamia, Thompson spent time in Lebanon, where he witnessed a severe famine.

It was while he was in Lebanon that Edward John met and courted Theodosia Jessup, the daughter of American missionaries. Theodosia and Edward John married in 1919. After the war, Thompson returned to Bankura College and resumed his teaching duties. His experiences in the army had greatly affected him, and ensured that he would not stay in his old job for long. Like so many European intellectuals, Thompson had found his faith in the progressive nature of Western civilisation had been badly knocked by the years of slaughter. Edward John was angry at the sacrifice of life he had witnessed, and believed that it must have been caused by some deep failing in the warring societies. Although he lay most of the blame for the war with the German side, he did not excuse Britain from culpability. In a letter to his mother, written near the end of the war, Thompson made his feelings clear:

If I live thro this War, I will stand, firmly and without question, with the Rebels. What we need is entire Reconstruction of Society. The old order is gone, & it was inestimably damnable when here. The East does things better, in a thousand things, than we do…this war has shown with sheets of flame that the whole system of things is wrong, built on blood and injustice. Thompson believed that events in Europe and the Middle East had endangered the British project in India, by associating the ‘advanced’ Christian civilisation Britain represented with death and destruction on an unparalleled scale. In a 1919 article for a Methodist magazine, Thompson insisted that:

The War has shocked India unspeakably, has seemed a collapse. It is felt by many that Christianity is discredited…for India now, everyone agrees, the overmastering sense and atmosphere is passionate nationalism. Thompson’s opinion of Indian civilisation was boosted by his partial disillusionment with the Western nations. He may well have been influenced in this respect by Tagore, who spent much of the war years touring the world delivering lectures critical of nationalism, imperialism, and Christianity to audiences keen to hear an Eastern verdict on the state of Western civilisation.

The end of the war coincided with an upsurge of Indian nationalism. Colonial authorities responded to calls for home rule, and even fully-fledged independence, with a mixture of incomprehension and brutality. The

Amritsar Massacre of 1919, which saw British troops firing machine guns into a huge crowd of unarmed Indians, came to symbolise all that was wrong with the British presence on the subcontinent.

In Europe, the end of the war came amidst a series of revolutionary upheavals created by economic chaos and disgust with ossified political systems, as well as war-weariness. Instability spread to Britain, where unemployed war veterans staged huge demonstrations in the late teens and early twenties.

Edward John Thompson’s disillusionment and anger worsened when he returned to Bankura College. EP Thompson notes that his father had, by 1920, ‘become a misfit in the Methodist Connexion’. Edward John’s experiences in the ‘war to end all wars’ made the jingoism and religious zealotry of many of his colleagues at Bankura intolerable. He showed his rejection of their worldview by simply refusing to talk with many of them. Thompson’s relations with Tagore soon also became troubled. The great poet disliked the long-gestating study of his work Thompson published in 1926, thinking it patronising and insufficiently sensitive to Bengali culture:

Thompson’s book…is one the most absurd books I have ever read dealing with a poet’s life and writings…being a Christian missionary his training makes him incapable of understanding some of the ideas that run through my writings…On the whole, the author is never afraid to be unjust, and that only shows his want of respect. I am certain he would have been much more careful if his subject was a continental poet of reputation in Europe. He ought to have realized his responsibility all the more because of the fact that there was hardly anyone in Europe who could judge his book from his own firsthand knowledge. But this has only made him bold and safely dogmatic… In the 1920s Thompson felt trapped between the poles of increasing Indian assertiveness and purblind British jingoism. Bryan D Palmer has summarised his situation:

Critical of brutal repression, he could lapse into a defensive posture concerning the benevolence of British rule and the care that some Englishmen, such as himself, had for Indian culture; drawn to the literary accomplishment of Eastern writers, Thompson extended them in his commentary the critical compliment of being ‘truthful’. Such a stand – for and against what was at stake in an England fractured along the lines of obvious oppositions – won Edward Thompson few allies. From Bankura to Boars HillIn 1923 Edward John Thompson left Bankura College and returned to Britain. His first child, whom he named Frank, after a brother who was killed at the Somme, had been born in Bengal the previous year; his second and last child would be born in Oxford, where Edward John and Theodosia settled after Edward John secured a job lecturing in Sanskrit, as part of the fledgling Department of Oriental Studies.

New frustrations were waiting at Oxford, as Thompson discovered that some of the attitudes which had infuriated him at Bankura had followed him home. Oriental Studies had little status at Oxford, where many of the Dons regarded Indian culture and Indian students with contempt. In a letter written in 1924 Thompson complained that:

There is no one to fight for Oriental Studies…every thing is a mess here. The library is in a mess, the Indian students are as un-understood and as much of a breeding place of discontent as ever, and there is no attempt to make the University and the public take India seriously. In 1924, Thompson’s friends at Oxford campaigned for him to be awarded an honourary Master of Arts degree, which would help him get a permanent position to the university, instead of the one year contract he then had. When his friends were rebutted, Thompson felt ‘more an outsider than ever’. In 1925 he did become an honourary fellow of Oriel College, which made him feel a little more secure, but through the rest of the ‘20s he would continue to rely on short-term contracts.

In 1925 Edward John and Theodosia began to build a house on Boars Hill for their young family. Boars Hill was a stronghold of the slightly Bohemian, literary side of Oxford society, and the Thompsons lived a stone’s throw from the poets

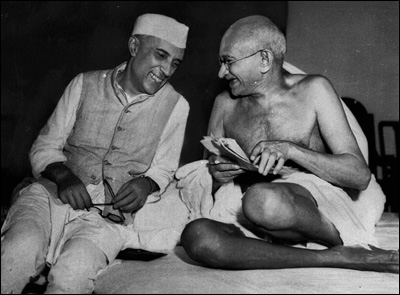

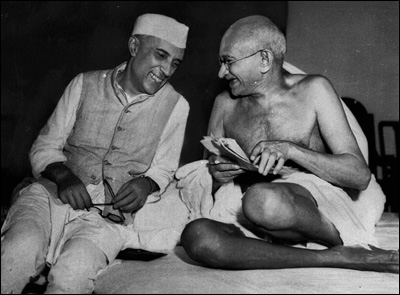

Robert Graves and Robert Bridges. Their new house became a meeting place for writers, for scholars of India, and for both Britons and Indians interested in the political situation on the subcontinent. In the 1930s, as Edward John became an active, if sometimes reluctant and equivocal, supporter of Indian independence, Jawarhal Nehru and

Mahatma Gandhi would both be visitors. EP Thompson would remember the ‘hushed, reverent’ atmosphere in the normally boisterous household when Gandhi visited, and the batting lessons that Nehru gave him on the Thompsons’ backyard cricket pitch.

In 1918 Edward John Thompson had promised to ‘stand with the rebels’ of the postwar world, but he did not seem to know exactly who the rebels were. Through the 1920s, especially, Thompson struggled to turn the anger and disillusionment the war had given him into a coherent political credo. He felt repulsed by the memory of war, and by the ongoing excesses of British rule in India, but he could find sympathy for neither the full-blooded nationalism sweeping post-war India nor the revolutionary socialism that seemed to threaten Britain, at least until the defeat of the General Strike of 1926. He was disgusted by the ignorant attitudes and ossified rituals of Oxford, but nonetheless craved acceptance and a permanent position there.

An Aside about Disillusioned British IntellectualsThompson’s rather incoherent sense of disillusion was representative of the feelings of many British intellectuals in the 1920s. The bitter experience of war and the knowledge of revolution on continental Europe had disrupted the cosy liberal consensus of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, but most intellectuals had not adopted or evolved any new worldview. Different ideological tendencies appeared amongst intellectuals in the years since the war, but none had become hegemonic, or even popular, and none acted as a bridge between the intelligentsia and the British ruling class, in the way that pre-war liberalism had done.

The 1920s did not see a large-scale migration of intellectuals to the left. A few did join the new Communist Party of Great Britain, and others tinkered with pre-war doctrines to come up with the ‘New Liberalism’ associated nowadays with John Maynard Keynes, but many others, including some of the most famous writers of the decade, espoused right-wing, quixotically reactionary ideas, as a clumsy response to the widely-perceived ‘crisis of civilisation’ that war and revolutions seemed to have announced.

The reactionaries tended to be creative artists, rather than scientists or bureaucrats. Key reactionaries included TS Eliot, who empathised with the Anglo-Catholic section of the ruling class and with a vision of a pre-industrial capitalist Britain and Europe; Evelyn Waugh, who espoused a sort of foppish Catholic semi-feudalism; and Wyndham Lewis, whose sympathy for fascism was really a sort of ultra-elitism.

There is no contradiction in the fact that many of the most important modernists, in the United States and Europe as well as Britain, were reactionaries. Faced with crisis in Europe and malaise in Britain, many artists and writers felt they needed to create new forms to contain and transmit the cultural inheritance they valued. Innovation often had conservative motives. ‘These fragments I have shored against my ruin’, Eliot wrote near the end of

The Waste Land.

An Ambivalent RebelThe incompleteness of Edward John’s radicalisation was reflected in the books he wrote during the 1920s. Perhaps the most important of these was

The Other Side of the Medal, a study of the

‘Indian Mutiny’ of 1857 that helped him win a reputation as a historian of the subcontinent. Thompson revealed a part of the purpose of his book when he complained in a 1924 letter that ‘the savagery which marks the outbursts of anti-European feeling’ in India was worst in areas that ‘were prominent in our Mutiny reprisals’.

The Other Side of the Medal

The Other Side of the Medal condemned the brutal behaviour of the British-led forces that repressed the Mutiny, and linked these depredations to the massacre at Amritsar. But Thompson’s condemnations were not accompanied by a call for British withdrawal from India. He wanted Britain to curb its excesses in India and thus restore the confidence of Indians in the Empire. Robert Gregg has noted that, far from being an advertisement for Indian nationalism, Thompson’s book was designed to counter an explosive anti-imperialist history of the mutiny published semi-secretly by

Vinayak Danodar Savarkar.

It was not until 1930, when he wrote a book called

Reconstructing India to coincide with a roundtable conference in London on the future of India, that Thompson advocated India’s right to independence. Even then, he hedged his bets by hoping that an independent India would form a permanent close alliance with Britain. Despite his qualified advocacy of independence and developing friendships with Indian nationalists like Nehru, Thompson retained a certain affection for British imperialism. In his long 1935 book

British Rule in India: Its Rise and Fulfilment, Thompson argued that:

Many special virtues, as well as failings, went into the building up of the British Empire…A high sense of duty, incorruptibility, a recognition of social responsibility, these may be remembered…[though] the moral and social prestige lost to the West by the war can never be removed. EP Thompson has suggested that from the end of World War One his father felt an ‘ambivalance’ about his Britishness, and that this ambivalence would ‘confuse his most radical writing’. What Edward John seems unable to reconcile, in his writing on India and on certain other subjects, is his deep love for English culture and history, on the one hand, and the repugnance he feels for many of the policies of contemporary British governments, on the other. It was always the Britain of Shelley and Shakespeare, not the Britain of Baldwin and Lloyd George, that Thompson wanted Indians to embrace.

Despite his halting movement to the left after World War One, Edward John never came to see the working class – and in India the peasantry – as a potential agent of progressive change. Despite his disappointment with successive post-war governments, Thompson remained wedded to the pre-war liberal notion that enlightened intellectuals could persuade the British establishment to follow progressive economic and political policies, if only the intellectuals framed their arguments well. This belief was generalised to other societies. Near the end of British Rule in India Thompson argued that:

Whatever degree of democracy may be condeded…India’s immediate future will depend, as in other countries, upon the wealthy and the educated. It must be many years before the villager gains a direct and decisive voice in provincial and federal affairs. A year after he wrote these words, Edward John sent a stern letter to his youngest son about the boy’s alleged lack of manners, claiming that ‘it is one of the things that mark the Englishman of class, that he is careful and proper always’. The former missionary could not slough off all the snobbery and national chauvinism he had learned.

‘Past all usefulness’ After a new world war broke out in 1939 Edward John showed his ambivalent, conflicted attitude towards Britain and its Empire by rejecting the political positions of the Quit India movement established by his friends Nehru and Gandhi. Nehru went to prison for opposing the war, on the grounds that Britain would not grant India immediate independence. Thompson, though, was eager to support the war effort, and soon became a YMCA worker attached to Royal Artillery Troops undergoing training in Britain.

Despite his strong desire to see a British victory, Edward John was plagued by continued doubts about the direction of his country, and of Western civilisation in general. In a 1940 letter to ‘Palmer’, as he called his youngest son, the former missionary argued that the world needed the sort of new direction that that only a ‘blazing faith’ could supply. The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany had that faith, even if it took a negative form, but ‘democracies’ like Britain did not – they were ‘self-indulgent and dithering’.

Thompson’s experiences in the YMCA seemed to bring back some of the frustrations he had felt decades earlier at Bankura. He gave lectures and religious counsel to the young soldiers, but claimed that neither did much good. When he gave a barracks hall lecture on ‘Greece and Its Importance to the World’, his audience was ‘one man who had wandered in by mistake’. The army, he complained, treated the YMCA as ‘well-meaning chumps who do a fine job in the tea and bun line’. Despairing of his efforts to help defeat Hitler, Thompson decided that he had lived ‘till past all usefulness’. He would die of cancer in 1946, shortly after receiving a letter of sympathy and thanks from Nehru, who was about to become the first Prime Minister of independent India.

The Making of Frank ThompsonIn

Beyond the Frontier, a book which investigated the last weeks of his brother’s life, EP Thompson described the atmosphere in the home that Edward John and Theodosia established at Boar’s Head:

That Frank Thompson was my brother tells us something: we shared the same parents and the same Oxford home which was supportive, liberal, anti-imperialist, quick with ideas and poetry and international visitors. We have seen that by the 1930s Edward John Thompson had become an established part of Oxford’s social and intellectual scene. A more secure contract and a string of well-reviewed books had helped make him feel more secure, and his home was a watering hole for writers, for liberal Dons, and for Indian nationalists. Both Frank and Edward Palmer Thompson were powerfully influenced by their parents’ interests and attitudes. They soon came to share their father’s great love of literature, as well as some of his political views. In a

1992 interview, EP Thompson explained how he had seen his father’s beliefs:

I acquired from my father the view that no government was to be trusted…that all governments were, in general, mendacious and should be distrusted. What comes through in this remark is EP Thompson’s awareness of his father’s deep but also unfocused disillusionment with British society and politics. Edward John’s failure ever to discover an alternative to what he deplored is reflected in his belief that governments ‘in general’, and not just governments representing one or another political ideology, are mendacious.

Edward John’s feelings must be understood in their context. Like other Western countries, Britain was affected badly by the Great Depression that began with the Wall Street crash of 1929. A minority Labour government elected in 1929 collapsed after only two years in power, and both the Labour and Liberal parties split, with a minority of Labour MPs and about half the Liberal MPs joining the Conservatives in a new ‘National Government’ which held power for the rest of the 1930s. This government has long been symbolised in the popular imagination by its last leader, Neville Chamberlain. Chamberlain’s name has become a byword for cowardice and incompetence, yet he was heading for a landslide election win when World War Two broke out in September 1939. Neither the Labour Party and its trade union allies nor the radical left succeeded in advancing a credible alternative to the National Government’s combination of economic austerity at home and appeasement of fascism abroad.

The bold ‘experiments’ of the Soviet Union’s five year plans and Roosevelt’s New Deal contrasted starkly with the British bourgeoisie’s tepid response to the Great Depression. No British Roosevelt or Hitler emerged to reorder British capitalism, and the hopes of some left-wing poets for ‘an English Lenin’ proved forlorn. Harry Pollitt disappointed Stephen Spender, and Oswald Mosley disappointed Lord Rothermere.

A peculiar mixture of frustration and impotence was felt in the 1930s not only by intellectuals like Edward John Thompson, but by sizeable numbers of people from all classes. Britain in the 1930s did not experience the sense of crisis common in many parts of Continental Europe, where the Great Depression and the polarisation of left and right opened up the prospect of social transformation, for good or bad. There were obvious deep-seated problems in 1930s Britain, but there was no sense that these differences would be resolved by social conflict. After the defeat of the General Strike of 1926 the threat of working class revolution had receded, and under the cynical and dull National Government that ruled for most of the thirties a sort of unhappy apathy reigned.

Even without his father’s influence, Frank Thompson would have been well aware of the malaise afflicting British and European society by the time he reached the end of his years at Winchester College in Hampshire, where he had proved a superb classical scholar and linguist, and begun to contemplate studies at his father’s university. In the autobiography he called

Disturbing the Universe, the physicist Freeman Dyson gave an account of Frank at Winchester:

Among the boys in our room, Frank was the largest, the loudest, the most uninhibited and the most brilliant…One of my most vivid memories is Frank coming back from a weekend in Oxford, striding into our room and singing at the top of his voice, “She’s got…what it takes.” This set him apart from the majority in our cloistered all-male society. At fifteen, Frank had already won for himself the title of College Poet. He was a connoisseur of Latin and Greek literature and could talk for hours about the fine points of an ode of Horace or of Pindar. Unlike the other classical scholars in our crowd, he also read medieval Latin and modern Greek. These were for him not dead but living languages. He was more deeply concerned that the rest of us with the big world outside, with the civil war then raging in Spain, with the world war that he saw coming. In the middle of 1936 war broke out in Spain, after a half-successful military coup against the country’s democratically elected government. The struggle in Spain would soon become a cause celebre for the left across Europe. With their contempt for democracy and brutal tactics, the forces led by General Francisco Franco showed the mendacity of the creed that had already won state power in Italy and Germany, and had recently come close to power in France.

The war in Spain also revealed the ineptitude and cynicism of the government in London, which refused to sell arms to the Republican government fighting Franco, and made it difficult for Britons who supported the fight against fascism to travel to Spain to offer their own assistance. Some members of the British government seemed to see the war as an obscure and irrelevant foreign affair; others were openly sympathetic to the fascist cause. To patriotic liberals like Edward John Thompson, who saw their country as an incubus for democracy, liberty, and civilised values, the attitude of the National government felt like a betrayal of Britain as well as Spain. The old wounds of World War One were reopened, as Britain once again seemed complicit in the needless slaughter of young men.

Some of Edward John’s neighbours on Boar’s Hill shared his opinions. Two young members of the Carritt family, which had lived next door to the Thompsons for years, took matters into their own hands and went to Spain as ambulance drivers attached to the British section of the International Brigade. Noel Carritt returned wounded, but his brother Anthony was not so lucky. Frank and Edward Palmer had grown up with the Carritt boys, whose father was a professor of philosophy at Oxford, and Frank had often discussed politics with Anthony.

Frank wrote poems to mark Anthony’s departure and death. In the first poem, written in the summer of 1937, Frank is aware of the distance between the pleasant life he is living in southern England and the situation in Spain. He is able to admire, but not share, Anthony Carritt’s urgent convictions:

Here, in the tranquil fragrance of the honeysuckle

The gentle, soothing velvet of the foxgloves,

The cuckoo’s drowsy laugh, - I thought of you,

The ever-whirring dynamos of your will,

Body and brain, one swift harmonious strength,

Flashing like polished steel to rid the world

Of all its gross unfairness. – But the grossest

Unfairness of it all is that tomorrow,

When both of us are gone, my sloth, your energy,

The world will still be cruelly perverse.

- Why not enjoy the foxgloves while they last? By the time he records Carritt’s death in the depths of December 1937, Frank feels that the horror of the real world encroaching on his pastoral England. He understands that his friend’s decision to fight in Spain might have been rational, as well as courageous. Yet he still cannot share Anthony Carritt’s creed:

A year ago in the drowsy Vicarage garden,

We talked of politics; you, with your tawny hair

Flamboyant, flaunting your red tie, unburdened

Your burning heart of the dirge we always hear –

The rich triumphant and the poor oppress’d.

And I laughed, seeing, I thought, an example of vague

Ideals not tried but taken on trust,

That would not stand the test. It sounded all too simple.

A year has passed; and now, where harsh winds rend

The street’s last shred of comfort – past the dread

Of bomb or gunfire, rigid on the ground

Or some cold stinking alley near Madrid,

Your mangled body festers – an example

Of something tougher. – Yet it still sounds all too simple. The changing face of communismIt is not surprising that Frank Thompson initially found Anthony Carritt’s politics hard to comprehend. The Communist Party had had little presence in the cloistered worlds of Oxford and Cambridge in the 1920s and early ‘30s. Those Oxbridge students and academics who were attracted to the party often found it a hostile place. Their class origins and their culture made them suspect, in the eyes of the party’s leadership. During the ultra-radical ‘Class Against Class’ period of the early thirties, when they followed Stalin’s lead by denouncing other organisations on the left and predicting imminent revolution, communist parties often demanded that student members give up ‘worthless’ academic work, become ‘proletarianised’, and devote virtually all of their time to political work.

The general failure of the ‘Class Against Class’ policy has come to be symbolised by the accession of Adolf Hitler to power in 1933. Together, Germany’s Communist and Social Democratic parties won more seats in the Reichstag than the Nazis in elections held at the end of 1932, but the Communists refused to work with their rivals against the threat of fascism. Declaring the Social Democrats ‘social fascists’ and coining the slogan ‘First Hitler, then us’, the party ensured its own destruction. Communists in other countries experienced less calamitous declines in their fortunes as a result of pursuing Class Against Class policies. In Britain, for instance, party membership plummeted, despite the onset of the Great Depression and mass unemployment.

In 1934 Stalin responded to the failure of Class Against Class and the complaints of communists by endorsing a policy of political regroupment which aimed to create very broad ‘Popular Fronts’. The new policy, which was formally adopted at the seventh and last congress of the Communist International in 1935, saw communists attempting to work not only with social democrats, but almost any political tendency opposed to ‘fascism and war’. In his unsympathetic study of the Popular Front, Brian Pearce noted the enormity of the policy shift it represented:

Between the beginning of 1933 and the middle of 1937 the international communist movement underwent one of the most startling transformations of policy in all its history. From relegation of virtually all other political trends, and especially the social democrats of all shades and grades, to the camp of fascism, it moved to a position of seeking a broad alliance inclusive of bourgeois and even extreme right-wing groups. From abstract internationalism it swung over to criticism of other parties for not being patriotic enough. Eric Hobsbawm has spelt out some of the assumptions that underlay the Popular Front strategy:

[T]he working class had been defeated [in Germany] because it had allowed itself to be isolated; it would win by isolating its main enemies…The policy assumed that fascism was a lasting phase of capitalist development, that bourgeois democracy was permanently abandoned as no longer compatible with capitalism, so that the defence of bourgeois democracy became objectively anti-capitalist. The Popular Front turn in party policy implied quite a different orientation toward once-scorned ‘bourgeois intellectuals’. Academics, writers, and artists who might be sympathetic to the party’s call for a broad anti-fascist alliance were assiduously courted. Margot Heinemann has described the logic behind the party’s new attitude:

To reclaim the best in past cultural traditions needed a broader and more flexible Marxist approach to history and the arts. What indeed would be the point of defending the cultural heritage against the Nazi book burners if it contained nothing but illusions and errors? James Klugmann, who trained as a historian before becoming a leading member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, used almost rhapsodic language to describe the effects of the Popular Front policy on communist intellectuals:

We became the inheritors of the Peasants’ Revolt, of the left of the English revolution, of the pre-Chartist movement, of the women’s suffrage movement…It set us in the right framework, it linked us with the past and gave us a more correct path for the future. In his

history of the Communist Party of Great Britain, Francis Beckett notes that Willie Gallacher, a leading party member, visited Cambridge shortly after the turn to the Popular Front and told communist students there that ‘it’s pointless to run away to factories’. Gallacher urged students to do well in their studies, announcing that the party needed ‘good scientists, historians, [and] teachers’. Beckett notes that, after the beginning of the Popular Front policy:

[T]he Communist Party and intellectuals felt close to each other…Poets, novelists, playwrights, actors and musicians, as well as economists and political philosophers, tried to make themselves comfortable in the Communist Party. In several European countries, Communists deployed the Popular Front with considerable success, in the short term at least. In France, for instance, the Communist Party helped forge a very broad anti-fascist alliance, incorporating political forces from the ‘patriotic right’ as well as the moderate and radical left, that set the stage for the accession of the Socialist Party’s Leon Blum to power in 1936.

In Britain, by contrast, the Popular Front never managed to unite even a sizeable minority of Britons in an alliance against fascism and ‘monopoly capital’. Except for a left-wing minority led by Stafford Crips, the Labour Party was indifferent to Communist blandishments. The party did attack the National government over its attitude to Spain, but it showed little interest in immersing itself in a Popular Front like the one that existed in France. Labour would not even wholeheartedly support the Aid for Spain campaign the Communists established. The Liberal Party was even less interested, and ‘patriotic’ Tories proved hard to find.

But the very failure of a Popular Front to take hold in Britain made the Communist Party an attractive proposition to young men and women who would never previously have thought of joining it. To a generation of Britons disillusioned by the failure of the establishment and its moderate opposition to confront the menace of fascism, the Communist Party suddenly seemed like the only organisation interested in defending democracy and liberty. With its calls for the defence of democracy across Europe, its invocation of Britain’s radical traditions, and its new-found enthusiasm for intellectuals and the arts, the party seemed to be defending territory ceded by more traditional parts of the British left. Walter Pierre put it well when he wrote that:

[W]ith the rising tide of the Depression and the collapse of the Labour Party…there seemed nothing to put between Europe (including Britain) and a generalised fascism except solidarity with the only remaining organised opposition, and that meant the still untarnished Communist Party. In an interview near the end of his life,

Edgell Rickword explained why he became a communist:

[T]he Communist Party seemed to be the only one that was actually doing something…Hitler was obviously beginning to run Germany along fascist lines, and was truly frightening, and the only organisation that seemed to take this at all seriously was the Communist Party…it represented something that was diametrically opposed to fascism. That was why I joined. The ‘new’ communism of the Popular Front era had an additional, subtler appeal for some intellectuals. In his 1937 book

Forward from Liberalism,

Stephen Spender explained why he and others like him had become sympathetic to the Soviet Union and its local allies:

[T]he liberal bourgeois individualist…suspects – and may suspect rightly – that this class to which he is confined and which possesses the treasury of all the world’s greatness, is nevertheless dead and unproductive, partly no doubt because its members are spiritually dried up by their common isolation. The real life, the real historic struggle, may, in fact, be taking place outside this country of fantastic values…he must express himself in the symbolic language of the existing culture, which is bourgeois…[yet] the future of individualism lies in the classless society. For this reason, social revolution is as urgent a problem for the [bourgeois] individualist as it is for the worker. For Spender, the liberal democratic discourses initiated by Godwin and Paine had foundered on the rock of capitalist class relations. Liberalism had atrophied because it was not possible to revolutionise the political and cultural superstructure of British society without changing the economic base of that society. The bourgeoisie and many of its intellectual defenders had not unnaturally drawn back from undermining the basis of their own power.

Spender cautions that the workers’ movement may not always be a force for civilization and a potential ally for intellectuals – he explains fascism as a symptom of the disappointment of the hopes of ‘the people’. Spender also warns about the potential for a philistine communism. It is important for intellectuals to intersect with workers, and to show workers the correct use of the cultural resources their coming accession to power will give them. The workers’ movement and the Communist Party was a place where bourgeois intellectuals and the best parts of the culture they represented might survive.

In his memoir of Cambridge in the 1930s, Marxist historian Victor Kiernan remembered a ‘very uncritical, almost mystical’ belief in ‘the working class and its mission to transform society’ – in the interests of intellectuals, as well as workers. Kiernan recalled the appeal of the Communist Party:

That capitalism was in its final stage appeared self-evident; the question was whether it would drag civilisation down with it in its collapse…The party was a twentieth century ark… Writing in the mid-thirties, John Strachey was blunter:

The middle classes of any country are much swayed by the same motives as other classes; and one of the most important, and most human, of the motives upon the strength of which men choose their political alignment, is the desire to be on the winning side. Like many intellectuals of his generation, Edward John Thompson had struggled to reconcile the slaughter of the First World War and the stagnation of inter-war Britain with the optimistic, nationalistic liberalism he had learned during the Edwardian era. Edward John felt that the civilisation he had loved and entertained such hopes for was in grave danger, but he could identify no force capable of defending it. For thousands of young British intellectuals in the second half of the thirties, though, the Communist Party and its international allies suddenly appeared to be the defenders of all that was healthy in British and European civilisation.

The crisis comes to OxfordIn

Beyond the Frontier, EP Thompson notes that by the time Frank went up to Oxford in 1937 he ‘had become very aware of the crisis of European politics’. The specters of fascism and war hung over the comfortable, sometimes frivolous life Frank enjoyed at Oxford; eventually, the threat these specters posed would persuade him to defy his parents and many of his friends by abandoning his studies and his old way of life.

At Oxford, Frank continued to show his outstanding ability as a classical scholar and a linguist; he also stepped up his production of poetry and performed in a series of amateur theatricals. A significant part of his time, though, was taken up by political activism. Frank developed a circle of close friends, including Iris Murdoch and the future historian and Labour Party politician MRD Foot, who shared both his intellectual appetite and his anti-fascist convictions. Although some of these friends supported organisations further to the left, Frank initially chose to join the Liberal Party’s university club. When he was made club secretary he tried hard to use the position to raise members’ awareness about Spain and the danger of fascism, but he soon became disillusioned, believing that campus Liberals were ‘too frivolous’. The dinner parties, dances and polite debates that party members enjoyed contrasted starkly with the relentless political activism of Oxford University’s Communist cadre. The Communists were a major force in the university’s Labour Club, which they had been allowed to join a couple of years earlier, in a rare Labour concession to Popular Front politics.

In September 1938 the ‘Munich Crisis’ brought Europe to the brink of war, and exposed the cynicism and cowardice of Neville Chamberlain’s government, which was prepared to allow Hitler to swallow Czechoslovakia rather than strike an anti-fascist alliance with the hated Soviet Union. Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement suddenly ignited political debate across Britain. Drusilla Scott remembered that:

The country was bitterly, passionately divided on this issue, and the split ran through the lines of party, family, class and all the usual groupings, in the same sort of way it did eighteen years later in the Suez crisis…there was certainly very widespread dismay and revulsion. In October, Oxford became the centre of the struggle over Chamberlain’s foreign policy, as AD Lindsay, the liberal former vice chancellor of the university, took on the Tory appeaser Quentin Hogg in a bitter by-election. Lindsay stood as an ‘Independent Progressive’ candidate, but his platform of opposition to Munich and support for a military alliance with the Soviet Union won him the backing of the Labour, Liberal, Communist parties, as well a few anti-Chamberlain Tories like Winston Churchill. It seemed as though a Popular Front might be coming into existence, in Oxford at least. Even the local Anarchist Union wrote a letter to Lindsay that offered a sort of backhanded support:

[T]he Anarchists of the University find it impossible to support your parliamentary campaign. In fact we are preparing a campaign against voting in any election. As, however, you are prepared to oppose Chamberlain, we would like you know that we will attempt to dissuade from voting only the supporters of Q. Hogg.

Both Edward John and Frank Thompson were strong supporters of AD Lindsay. Frank and his friends threw themselves into the short but intense election campaign, canvassing and distributing leaflets across Oxford, and watching while Lindsay and Hogg spoke to large and impassioned crowds on street corners. The ‘most hectic ten days in Oxford since the Saint Scholastics’ riots in the fourteenth century’ ended with a win for Hogg. The Tory majority had been halved, but Frank and his friends were bitterly disappointed. In a memoir called ‘Snapshots of Oxford’, Frank remembered the night Hogg’s victory was announced:

We felt glum that night…we were like rags soaked in cold vinegar. Someone grew bitter: ‘I hope North Oxford gets the first bombs’…Michael [MRD Foot] looked fiercely at the ground…’There are only two alternatives now – to join the Communist Party or abdicate from politics. I can’t swallow communism so I’ll abdicate and take up psychology.’ Frank Thompson was in no mood to abdicate from politics, even when the defeat of Lindsay was followed a few months later by the final collapse of Republican Spain. In a poem written early in 1939, Frank sees the defeat as merely ‘the first round’ in a struggle that he will soon join:

We shall enter, the new protagonists,

Not forgetting, not forgiving:

This time the winds may whisper across the sierras

‘At last they are coming to give you the freedom they owe you.

Very late, very late they remember to help their friends.By the time he had written these defiant lines, Frank Thompson had joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. Iris Murdoch, whom he had nicknamed ‘Madonna Bolshevika’, had suggested he join the party after hearing him complaining about the other left groups on campus at a drunken party. Frank threw himself into work for the communists, attending meetings, selling the

Daily Worker, and helping recruit other students. Joining the party did not, however, imply any sudden conversion to Marxism. Frank, who by 1939 could already read four languages, liked to boast that he had never opened Marx’s

Capital. In

Beyond the Frontier EP Thompson makes the nature of his brother’s politics clear:

Frank Thompson can scarcely be defined as an orthodox communist…in 1939-40…[t]he basis for the commitment [to the party] lay in an internationalist anti-fascist contestation, in an era of Western ruling class appeasement, non-intervention (but effective complicity with reaction) in Spain…[and] inertia in the face of depression, unemployment and severe hardship of every kind…The Communist Party was seen, first of all, as the universal organiser of resistance…The commitment to something called Communism was political and internationalist. In Britain at least it entailed…rather little commitment to any doctrinal orthodoxies…There are few references to Marx and Marxism in Frank Thompson’s letters, and more than one of these is ironic. Like many young Oxbridge students, Frank joined the party not because he believed in the tenets of ‘dialectical materialism’ or the political economy of Capital, but because the party seemed like an ‘ark’, in which the best aspects of the Old World might be protected, even as the New World came into being amid apocalypses of economic collapse and war. The ark would be staffed by ‘the people’, a shifting ensemble recruited from all classes and all nations, but led, nominally at least, by an idealised working class. The revolutionary role of the ‘the people’ derived not from some ‘objective’ economic position that they occupied in capitalist society, but from an awareness of the struggles for freedom in the past and a knowledge of the necessity of defeating fascism in the thirties.

‘I simply want to fight’On the second of September 1939 – a day after the Nazi invasion of Poland, and a day before the British declaration of war – Frank Thompson shocked his friends and family by enlisting in the army. Frank’s parents argued that he was too young to fight, and ought to finish his degree, while Iris Murdoch pointed out that the Soviet leadership and – after a week of confusion – the local Communist Party had characterised the war as ‘social imperialist’, and ordered members not to fight in it. Frank explained himself in a poem called ‘To Madonna Bolshevika’:

Sure, lady, I know the party line is better

I know what Marx would have said. I know you’re right

When this is over we’ll fight for the things that matter

Somehow to-day I simply want to fight.

That’s heresy? Okay. But I’m past caring.

There’s blood in my eyes, and mist and hate.

I know the things we’re fighting now and loathe them.

Now’s not the time you say? But I can’t wait.

In ‘Snapshots of Oxford’ Frank gave an account of his last night at Oxford which captures the contradictions in the life he had led there:

In Corpus [Christi, Frank’s college] everyone stands one’s drinks and I was pretty whistled…After I had two tulips in the quad and bust a window, they dragged me into Leo’s room and sat on me. I clamed down and they thought I was safe enough to take on the river. The red clouds around Magdalen tower were fading to grey, when we met two people we didn’t like. We chased them and tried to upset their canoe. We got slowed up at the rollers, and then I dropped my paddle. With the excitement all the beer surged up in me. Shouting the historic slogan ‘All hands to the defence of the Soviet fatherland!’ I plunged into the river. They fished me out but I plunged in again. By a series of forced marches they dragged me back and dumped me on the disgusted porter at the Holywell gate. After quoting this passage in his biography of Iris Murdoch,

Peter Conradi adds that:

After Frank had burst into an ‘important meeting of the college communist group’ Comrade Foot, by unanimous vote, was given ‘the revolutionary task of putting him to bed’. ‘The blackthorn will soon be out’Frank continued to support the Communist Party, and was naturally pleased when it fell in behind the war effort after the invasion of the Soviet Union in May 1941, but his commitment to a radical liberal politics rooted in his reading of English history and literature trumped his commitment to the party line. For Frank, the new war was a colossal struggle between the forces of civilisation and democracy, spearheaded after May 1941 by the Soviet Union, and the forces of tyranny and obscurantism. Communism was simply the culmination of the struggle to preserve all that was best in European civilisation from the fascist monster spawned by capitalism’s breakdown in the thirties. To the extent that it was valuable, Marxism was not a break from liberalism, but a development of it.

It should be clear from our earlier discussion of Popular Front communism that Frank Thompson’s views were by no means eccentric at the end of the thirties and in the early forties. Eric Hobsbawm, who was an undergraduate at Oxford at the same time as Frank, has described the same type of thinking in the young members of what would eventually be called the Communist Party Historians Group:

We were always (at least I was, and several other people, I’m sure, also were) instinctively ‘popular fronters’. We believed that Marxist theory was…the spearhead of a broad progressive history…We saw ourselves as trying…to push forward that tradition, to make it more explicit… In his study of the Communist Party’s relationship with writers and artists, Andy Croft commented perceptively on the syncretism of the young intellectuals attracted towards the party during the Popular Front era:

[N]o one should be surprised if British Marxists…blended liberal, Romantic, non-conformist and socialist utopian traditions with Marxist theory. These were simply the traditions which best answered the desire to close the widening gap between the world as it was and the aspiration of writers and artists for a humane society. After he was posted abroad in 1941, Captain Frank Thompson sent home a stream of letters and poems which showed that his core political beliefs had not changed. Patriotism, anti-fascism, and staunch support for the Soviet Union often rubbed shoulders in these communications. A letter written during a pause in the campaign to liberate Sicily showed how romantic and intense Frank’s sense of Englishness could be:

It’s humiliating, just sitting round while the Yanks, the Chinks and the Russkies teach us how to fight…At home the blackthorn will soon be out. Blackthorn symbolises for me, more than any other flower, the loveliness of the English spring. It symbolises, too, the light-hearted strength and cleanliness of spirit which has been one of England’s best features, and will, I hope, be so again. That sounds rather stilted, but I guess you know what I mean. For communism, and for libertyIn the middle of 1944 Edward John wrote to his youngest son, who was fighting his way up the Italian peninsula as commander of a tank brigade:

This is a sad letter to write to you, Palmer, old chap. Yesterday we read a wire that Major WF Thompson has been ‘missing’ since May 31…We do not even know where Frank was…He deliberately did the most dangerous and adventurous job there was, and he did it magnificently. The Thompson family eventually learned that

Frank had disappeared while serving as an Intelligence Officer amongst a group of partisans in Bulgaria. Frank had volunteered to act as a link between the British army and the anti-fascist fighters of the Balkans, and had already fought bravely in southern Yugoslavia before crossing the border into Bulgaria. The war was nearly over in Europe by the time that Edward John and Theodosia received the news that Frank had been executed by a fascist firing squad in a remote part of Bulgaria, after being captured with a few partisans and given a show trial. After the war, an eyewitness to Frank’s last days was able to flesh out the bare report offered by the British army:

When he was called for questioning, to everyone’s astonishment he needed no interpreter but spoke in correct and idiomatic Bulgarian. ‘By what right do you, an Englishman, enter our country and wage war against us?’ he was asked. Major Thompson answered, ‘I came because this war is very much deeper than a struggle of nation against nation. The greatest thing in the world now is the struggle of Anti-Fascism against Fascism…I am ready to die for freedom. And I am proud to die with Bulgarian patriots as companions’…

Major Thompson then took charge of the condemned and led them to the castle. As they marched off before the assembled people he raised the salute of the Fatherland Front which the Allies were helping, the clenched fist. A gendarme struck his hand down. But Thompson called out to the people, ‘I give you the salute of freedom’. All the men died raising this salute. The spectators were sobbing. It is characteristic that Frank Thompson, a Communist Party member who had been fighting alongside Bulgarian party members, should present his beliefs as anti-fascist, rather than communist or Marxist. It is not that Frank would have been ashamed of his membership of the party, or the beliefs of his comrades in arms. It is simply that, for him, communists were the vanguard of the global struggle of the forces of liberty against the forces of fascism. The fight for communism was understood as a part of the fight against fascism. A similar sentiment is found in one of the last poems of John Cornford, another Oxford Communist who died fighting fascism:

Raise the red flag triumphantly

For communism and for liberty.

EP Thompson’s inheritanceLet us try to draw together some of the threads of the stories of Edward John and Frank Thompson, and relate them to the story of Edward Palmer Thompson. Edward John had been a fairly typical liberal British intellectual, until he was radicalised by his experience of British imperialism in India and the First World War. His own difficulties as a junior lecturer at an ossified Oxford and a jobbing writer in a philistine culture reinforced his discomfort with key aspects of British society. But Edward John’s awareness of the deep malaise in British society was not matched by a commitment to a radical alternative to the status quo. The former missionary had little faith in Britain’s political elite, but he had even less faith in the ordinary people of Britain and India.

Edward John remained a liberal, albeit an embittered, radicalised liberal. His youngest son inherited many of his attitudes and sympathies. Even before he left school, Frank Thompson was aware of the threat that fascism posed to the values and culture he had been raised to love. At Oxford Frank came to realise that Britain’s political establishment and its traditional left-wing parties were unwilling to face down the fascist threat. Some parts of the establishment even seemed to welcome the success of fascism in Spain. The Munich crisis of September 1938 stirred debate in Britain about the fascist threat, and briefly pushed the Labour and Liberal parties leftward, but the defeat of AD Lindsay in Oxford’s by-election showed that much of the population still supported Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement.

We have seen that Frank’s disillusionment with the miserable Britain of the interwar years did not stop him from being a patriot. Like his father, Frank cherished Britain’s liberal political tradition, as well as the cultural tradition represented by names like Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and Ruskin. Like many young men and women in the 1930s, Frank came to feel that the best parts of British and European civilisation could no longer be defended by either the liberal or conservative ends of the traditional political establishment. It was in the Communist Party of the Popular Front era, which presented itself as the guardian of British culture and British radical history, and the local vanguard of the international fight against fascism, that Frank Thompson eventually found a political home.

It would be wrong to conflate the characters, interests and abilities of Frank and Edward Palmer Thompson. A comparison of the brothers’ early poems shows that Edward Palmer’s are demotic and full of down to earth imagery, while Frank’s are characterised by rococo rhyme schemes, Latinate phrases and allusions to classical literature. The different styles reflect important differences of chracter. Edward Palmer lacked his older brother’s passion for antiquity and aptitude for languages. He was ill at ease with Frank’s over-refined Winchester friends, doubted whether university would suit him, and in the middle of 1939 briefly alarmed his parents by announcing he wanted to drop out of school and work on a farm.

Despite these differences, there is no doubt that Frank exerted a profound influence on his younger brother, before and after his departure to the war. EP Thompson himself has remembered admiring his elder brother ‘as one can only admire a genius’, and appreciated the way that Frank Thompson’s entry into the Communist Party ‘made it easier for me’. The two men shared a commitment to the politics of the Popular Front, and to the conception of the Communist movement as an outgrowth of a long indigenous tradition of radical liberalism. Both men saw the Popular Front as the alternative to the disillusioned negativity that their father often exuded. The Popular Front were a way of renewing the optimistic liberalism that Edward John had lost long ago, by marrying a radicalised liberalism to a belief in the power of ordinary people to determine the course of history.

Edward Palmer’s respect for his elder brother was not unreciprocated. In a 1941 poem called ‘Brother’, Frank leaves no doubt that he considered his seventeen year-old sibling a comrade and co-thinker:

To keep aloof, my comrade, my brother from you

And others, not of our blood, but brothers too

With whom our roots are locked. Why is the hill

Larch-lovely, split with hostile coppices?

Why is there limit set on our goodwill?

Make this our task – out of a time-stained world

Often invoked but rarely true, to weld,

A slogan that will galvanise the world. In one of the last letters he sent home, Frank told Iris Murdoch that at the end of the war, ‘whether I’m here or not’, she should collaborate with his younger brother on a work of political theory. The clear implication is that Edward Palmer holds many of the same ideas that Frank and Iris have shared.

The seventeen year old EP Thompson came up to Cambridge at the beginning of 1941. A few months earlier the Chamberlain government had finally imploded under the weight of its ineptitude and cowardice, and Winston Churchill had formed a new, much more broadly-based administration that aimed to unite the whole country against the Nazi war machine that had rolled to the edge of the English channel. In bringing Labour politicians and trade union leaders closer to the centre of power and agreeing, albeit reluctantly, to recognise the Home Guard militia that had sprung up around the country, Churchill fulfilled some of the demands that advocates of a Popular Front against fascism had made of the Chamberlain government. When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union a couple of months after Edward Palmer reached Cambridge, the Communist Party had no hesitation in dropping its anti-war stance and throwing itself completely behind the Churchill administration.

By 1941, the ‘frivolity’ that had annoyed Frank had vanished from Oxbridge. Students like Edward Palmer were aware that their studies would soon give way to military service, and they took a keen interest in international politics and the course of the war. Cambridge boasted a thousand-strong Socialist Club which united Labourites, left-wing Liberals, and Communists.

If anything, the politics of the Popular Front were stronger in the Communist Party during the war years than they were during the second half of the thirties. The party still identified itself as the continuator of an indigenous British tradition of radicalism with roots in the seventeenth century, the young Wordsworth, and Chartism. It saw victory against fascism as a precursor to a post-war social transformation that might now be achievable without violence.

Strikes were discouraged, party factory branches were abolished, and Trotskyists who preached opposition to the Churchill government were denounced as Fifth Columnists and beaten up. The party became so wedded to the idea of a Popular Front government that during the 1945 election campaign they argued that a new Labour-led government should share power with Tories as well as Communists.

In 1940, Christopher Hill had brought the Popular Front into academic discourse by publishing the first draft of his reinterpretation of English history. Hill’s notion of the English Civil War as a revolutionary struggle against obscurantism and tyranny had a powerful appeal for a generation of intellectuals facing the menace of fascism. In the last interview he gave, EP Thompson remembered being inspired by Hill’s study when he was still a schoolboy. Thompson was also strongly influenced by the

Handbook of Freedom, an anthology of radical writing edited by Jack Lindsay and Edgell Rickword. In 1979 he would pay tribute to the text:

This extraordinarily rich compendium of primary materials was selected from twelve centuries of ‘English Democracy’. It is impressive for its length of reach (one hundred pages, or one quarter of the book, precedes 1600); the diversity and catholicity of the sources drawn upon, bringing, with a sense of recognition, unlikely voices into a common discourse; the generosity of the editorial minds which called such diverse values into evidence; and the implicit intellectual command not only of these various sources but also of the wider historical process out of which these voices arose.

I think that the Handbook of Freedom was among the two or three books which I managed to keep around with me in the army. Certainly I know that others did so. It is significant that Rickword and Lindsay were both poets, and that their book drew on poetry as much as political economy. EP Thompson had learned a deep love of both literature and his British heritage from his father and brother, and he would have been impressed by the Popular Front-era Communist Party’s attentiveness to both.

When he returned from the war in 1945, EP Thompson set to work editing a collection of Frank Thompson’s poems, letters, and journals. There Is A Spirit in Europe was published by Victor Gollancz in 1947, with an introduction, conclusion and extensive notes by Frank’s younger brother and an afterword written by Edward John Thompson on his deathbed.

By 1947, many of Frank Thompson’s hopes for the postwar world had been betrayed. The Cold War was beginning, Europe was being divided, Britain and the other old imperial powers still clung to most of their empires, and new wars were brewing in the far East. Inside the Communist parties of the West, the Popular Front policy was in disarray, and intellectuals were being subjected to

Zhdanovism, the new Kremlin dogma which insisted on a sharp divide between ‘bourgeois’ and ‘proletarian’ culture and science.

But

There Is A Spirit in Europe was not just a memorial to Frank Thompson and the ideas which were so cruelly mocked by the post-war world. For Frank’s brother, the book was also a manifesto. For almost five decades, Edward Palmer Thompson would remain loyal to the ideas he had learned from his father, his brother, and from the Communist Party of the late 1930s and the first half of the 1940s. Thompson would take these ideas into a succession of political organisations and campaigns, refine and rename them in a score of polemics and meditations, and apply them with enormous success to the study of history and literature, but they had their origin in the first era of the Popular Front, when the Communist Party of Great Britain briefly seemed to offer a bridge between the radical liberal tradition of the ‘freeborn Englishman’ and the twentieth century struggle against fascism and decrepit capitalism.

Frank Thompson died near the end of the golden age of the Popular Front against fascism, but his younger brother would hold on to the ideas in

There is a Spirit in Europe despite heavy criticism from left and right. These ideas were a constant stimulus to Thompson’s scholarship, as well as his political activism; their shadow hangs over the

Making of the English Working Class as well as

New Reasoner and the

May Day Manifesto.

Only at the end of the 1970s, under the pressure of insuperable intellectual and political contradictions, would Thompson withdraw from the battle for the ideas he acquired in the ‘heroic decade’ between the mid-30s and the mid-40s, and search half-heartedly for a new synthesis of ideas capable of integrating his political and scholarly work, and of giving his life meaning.