From the late 1970s until his sudden death last Thursday, Roger Fox was a pillar of left-wing activism in New Zealand. Roger was arrested at Auckland airport for demanding East Timorese independence, batoned and imprisoned on the East Coast during the 1981 Springbok tour, and thrown into a paddy wagon outside Auckland's British consulate after the invasion of Iraq. His first loyalty was to the union movement, but he was active in a huge number of campaigns, from the movement against genocide in East Timor to the fight for Maori land rights to the struggle to end discrimination against disabled New Zealanders. Roger stood on hundreds of picket lines, and spoke to scores of rallies and meetings.

Sometimes activism brought Roger into the spotlight - in 2005, for instance, he ended up on the front page of the

New Zealand Herald after gatecrashing one of Don Brash's (in)famous speeches to the Orewa Rotary Club. Usually, though, Roger worked behind the scenes, at the grassroots of trade unions, United Fronts, and community organisations. For him, activism was about discussions in committee meeting rooms, poster runs on weeknights, door knocking in the rain, and leafleting stopwork meetings.

It was hard, unglamorous work, but Roger was indefatigable. He maintained his activism in the face of police intimidation, surveillance from the Security Intelligence Service, personal tragedies, falling-outs with other comrades, ugly encounters with Stalinist politics, and the serious defeats which the left suffered in the 1980s and '90s. Many other activists burned out, or retreated to the minutae of theory, or discovered the virtues of the free market; Roger persisted with his leaflet drops, his soapbox speeches, and his door knocking. The tenacity and energy Roger showed through so many difficult years makes his sudden death from a heart attack at the age of only fifty doubly shocking.

Roger grew up on a dairy farm in the Kaipara. After moving to Auckland to attend university in the mid-70s, though, he fell in love with city life. Roger liked to talk self-deprecatingly about his first attempt at political activism: appalled by Indonesia's genocidal conquest of East Timor, he put on a balaclava, nailed together and painted a placard, and staged a secret, one-man demonstration outside the Indonesian consulate in Auckland. 'I was completely innocent about collective action and the ABCs of the labour movement, then', he remembered.

Roger learned his ABCs during the crisis-ridden years of the late '70s and early '80s, when an unpopular but deeply cynical Muldoon government clung to power by a combination of draconian price and wage controls, redbaiting, and Maori-bashing. Roger's old friend Peter Gleeson recalled that the struggle by Auckland Maori to win back Bastion Point was a turning point in Roger's political evolution. 'When I first met Roger at university he was a fairly conservative chap', Peter remembered. 'He wore these awful long shorts and wanted to be an accountant. I think he went up Bastion Point during the occupation to find out what all the fuss was about. He found out what all the fuss was about.'

Roger's involvement in the campaign to win back Bastion Point paved the way for his involvement in the protests against the 1981 Springbok rugby tour. His marriage to a Samoan New Zealander deepened his contacts with the Polynesian community and his involvement in anti-racist politics.

In the 1980s, Roger found a temporary political home in the Communist Party of New Zealand. He was attracted by the party's militancy, and the fact that the vast majority of its members were blue collar workers with deep roots in the union movement. Roger learnt some valuable lessons from these members about the importance of workplace organising, but he quickly became disturbed by the party's admiration for Stalin and for the Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha. When the demented Hoxha killed his second in command for being a 'CIA-KGB spy', Roger raised the issue inside his Communist Party branch. 'It was like farting in church', he remembered.

Parting company with the Hoxhaites, Roger decided that Trotsky rather than Stalin represented the true spirit of the Bolshevik revolution. To the end of his life, Roger would be a stern opponent of Stalinism in the left and the labour movement, and a tireless proponent of grassroots democracy in unions, political parties, and United Fronts. Unusually, though, Roger complemented his admiration for Trotsky with a strong interest in Buddhism. Roger was particularly drawn to Theravada Buddhism, a religious and philosophical tradition which is strong in Burma. Roger would sometimes go straight from a political meeting to a gathering at his local temple; to the alarm of both his political comrades and his fellow Buddhists, he liked to argue that Buddhism and Marxism were doctrines that naturally complemented each other. 'Marxism is for the material side of my life, and Buddhism is for the other side', he explained.

From the late seventies until the end of his life, Roger was affected by the strange, cruel disease known as manic depression. Roger’s illness meant that he rarely worked for a wage; he liked to think of himself as a professional activist. I remember a heckler approaching an anti-war protest outside the US consulate and shouting ‘Get a job, you bloody lefties’; Roger’s immediate response was ‘Sorry, comrade – I’m on strike for life against the Protestant work ethic!’ Roger’s illness gave him a deep empathy with other vulnerable and marginalised members of society, and he worked tirelessly to befriend and politicise mentally ill and physically disabled people. After he joined the Alliance several years ago the party recognised his insights by making him its Spokesperson for Disabilities.

During the eighties and nineties Roger was repeatedly hospitalised, but in the last years of his life he suffered far fewer of the uncontrollable highs and deep lows associated with his condition. In the past couple of years he seemed to have reached something like a point of balance, and to be more at peace with himself than ever before. Roger took great pride in his wide circle of friends and his beautiful, gifted daughter. He talked optimistically about the future.

I got to know Roger after joining the Anti Imperialist Coalition, a United Front of groups and individuals that coalesced in the aftermath of 9/11 to oppose George Bush’s imperialist War of Terror as well as Osama bin Laden's atrocities. Roger threw himself into the AIC with a passion. Our Wednesday night meetings were, he said, the highlight of his week, and he would prepare meticulously for them. Roger was particularly excited by the involvement of Auckland’s Middle Eastern communities in the new movement. He was soon leafleting the local mosque and bringing members of the Iraqi and Pakistani communities to our meetings. We were not surprised by this - Roger was renowned inside the AIC for his ability to make new political contacts and get them along to meetings. Almost every week he would have a new face to introduce to us.

Roger was also renowned for thinking one or two steps ahead of the rest of us. If we organised a successful street meeting, Roger would be discussing the need for a march. If we distributed a leaflet, Roger would be talking about the prospects for a newspaper. If we persuaded a union to pledge support for the anti-war movement, Roger would be making the argument for a general strike against the war. At the beginning of 2002, when the movement against the invasion of Afghanistan had dissipated and Bush’s foreign policy seemed triumphant, Roger was already predicting the invasion of Iraq and talking of the need to prepare for the rise of a massive new anti-war movement.

Roger’s intensity could sometimes mean he made mountains out of molehills. I remember him standing in front of the AIC demanding that we take a vote on the ‘crucial question’ of the arrangement of the plastic chairs in our meeting room. Roger was adamantly opposed to the ‘bourgeois’ practice of arranging the chairs in a large circle – he wanted them in rows instead. ‘The circle symbolises completion’, Roger complained, ‘and we want this organisation to grow. I should have the right to sit in the back row, and read the newspaper, and pick my nose, without everybody else seeing me...that’s labour movement discipline, and besides, this circle seating reminds me of the therapy groups in psych hospital’. The meeting dissolved into laughter; Roger was eventually able to crack a smile.

I had my last conversation with Roger after one of last year’s protests against the police invasion of Tuhoe Country and the imprisonment of the Urewera 16. After marching to a big rally outside Mt Eden Prison, some friends and I ducked into a nearby pub for a few beers, then trekked back to Queen Street to our car. On our way back we spotted Roger outside the Town Hall with a small group of Tuhoe who were waiting for a bus back to the Ureweras. In between finishing off some of their food, Roger was giving his new friends and everybody else within earshot a good-humoured lecture about the way to defeat the New Zealand state and free the Urewera 16. ‘We can’t rely on the media or on John Minto or any other big leader’, Roger insisted, waving a half-eaten orange in one hand. ‘We need the grassroots. Democracy, direct action, and LABOUR MOVEMENT DISCIPLINE! It’s ordinary people that change the world.’

That last sentence ought to go on Roger Fox's gravestone.

You can find the details of Roger's funeral and other tributes to the man

here.

Skyler and I recently made our second trip to Pureora Forest Park, the sprawl of ancient podocarps preserved by the efforts of tree-climbing hippies back in the late 1970s.

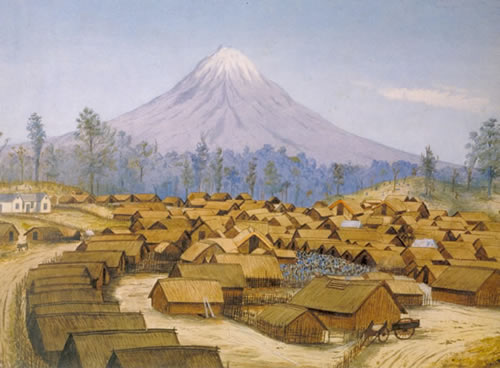

Skyler and I recently made our second trip to Pureora Forest Park, the sprawl of ancient podocarps preserved by the efforts of tree-climbing hippies back in the late 1970s.  These mountains help to mark the western edge of the rohe of the Tainui peoples, and they were close to the border of the Rohe Potae, or 'Country of the Hat', which existed as a de facto independent state in the central North Island between 1864 and 1883.

These mountains help to mark the western edge of the rohe of the Tainui peoples, and they were close to the border of the Rohe Potae, or 'Country of the Hat', which existed as a de facto independent state in the central North Island between 1864 and 1883.  The high plain that borders the forest on the north has a strange quality, especially when a dry summer drains it of colour. The porous limestone rocks of the King Country and the hard volcanic rocks thrown up by the repeated eruptions that made Lake Taupo are scattered across sheep country that has been unwisely converted into dairy farmland in recent years. In between the farms are blocks of doomed radiata pine, planted when the pumice soil of the plain was not thought capable of sustaining sheep, let alone cows.

The high plain that borders the forest on the north has a strange quality, especially when a dry summer drains it of colour. The porous limestone rocks of the King Country and the hard volcanic rocks thrown up by the repeated eruptions that made Lake Taupo are scattered across sheep country that has been unwisely converted into dairy farmland in recent years. In between the farms are blocks of doomed radiata pine, planted when the pumice soil of the plain was not thought capable of sustaining sheep, let alone cows.

The track to the summit of Pureora starts about seven hundred metres up, at the edge of a road built to take logging trucks to the radiata. The rimu and matai (red and black native pines) on either side of the road grow as high as eighty feet. Some isolated trees are protected in the midst of radiata and farmland; through the mist, they look like giants striding south, back to the safety of the virgin forest.

The track to the summit of Pureora starts about seven hundred metres up, at the edge of a road built to take logging trucks to the radiata. The rimu and matai (red and black native pines) on either side of the road grow as high as eighty feet. Some isolated trees are protected in the midst of radiata and farmland; through the mist, they look like giants striding south, back to the safety of the virgin forest.

As the track climbs higher up the northern side of Pureora, the huge podocarps drop away, and a so-called 'goblin forest' begins. The air is damp, and epiphytes and creepers hang from or scale the trunks and branches of smaller trees. In A Ride Through the Disturbed Districts of New Zealand, his ill-tempered portrait of the wartorn North Island of 1870, Herbert Mead remembers the goblin forest of Pureora with a certain dread:

As the track climbs higher up the northern side of Pureora, the huge podocarps drop away, and a so-called 'goblin forest' begins. The air is damp, and epiphytes and creepers hang from or scale the trunks and branches of smaller trees. In A Ride Through the Disturbed Districts of New Zealand, his ill-tempered portrait of the wartorn North Island of 1870, Herbert Mead remembers the goblin forest of Pureora with a certain dread:  The pumice soil of the Pureora area absorbs water very slowly, so that swamps and lagoons form easily, even in the midst of high-altitude bush. These 'mountain mires' are exceptional in New Zealand, where most wetlands are found at low altitude. Trampers have to watch their step.

The pumice soil of the Pureora area absorbs water very slowly, so that swamps and lagoons form easily, even in the midst of high-altitude bush. These 'mountain mires' are exceptional in New Zealand, where most wetlands are found at low altitude. Trampers have to watch their step. From the top of Pureora, the forest stretches away to the south, bordered on the east by Lake Taupo and on the west by the scruffy farms of the King Country.

From the top of Pureora, the forest stretches away to the south, bordered on the east by Lake Taupo and on the west by the scruffy farms of the King Country.