Playing the history card

Every now and then New Zealand's nineteenth century history disturbs the surface of contemporary political discourse, like a taniwha rising from its slumbers at the bottom of a lake whose depth and coldness had been forgotten. Speaking to a mostly Maori audience in Wanganui last week, John Key was foolish enough to dip his toe into the deep waters of the past. Before his incredulous audience, Key insisted that:

Every now and then New Zealand's nineteenth century history disturbs the surface of contemporary political discourse, like a taniwha rising from its slumbers at the bottom of a lake whose depth and coldness had been forgotten. Speaking to a mostly Maori audience in Wanganui last week, John Key was foolish enough to dip his toe into the deep waters of the past. Before his incredulous audience, Key insisted that:One of the unique things about New Zealand is that we are not a country that's come about through civil war or a lot of fighting internally. We're a country that peacefully came together - Maori and the Crown decided from both partners' side that it was in their interests to have a peaceful negotiation. That's what the Treaty was, a founding document - a development document - for New Zealand, and I think that we could work things out in a peaceful, sensible and mature way has actually been a defining part of New Zealand's history. It's very important, and it's important we honour that now.

I'd wager that all that feel good rhetoric would have gone down better at the Orewa Rotary Club than on a marae in the heart of a district which hosted some of the most bitter battles of the New Zealand Wars. The Maori Party was quick to give Key a serve; Labour duly followed, like the cowardly schoolboy who comes to a fight late and aims a couple of opportunistic blows. But the party that gave us the Seabed and Foreshore Act was soon stopped in its tracks, as National Party staff dug up a speech by Michael Cullen that was just as asinine as Key's Wanganui homily.

Undeterred by notions of consistency, some of Labour's supporters in the blogosphere have managed to maintain a tone of righteous indignation about Key's ignorance of New Zealand history for days on end. On blogs like The Standard Key's speech has been recapitulated and ritually denounced in post after post.

The authors of The Standard may have seized on the speech Key made in Wanganui last week, but they have not noticed that the man's attempt to clarify the meaning of that speech was itself deeply dubious. It has been left to that venerable voice of the right, the Granny Herald, to point out Key's latest blunder:

Last week, Key left himself open to doubt that he knew the country's history when he said: "One of the unique things about New Zealand is that we are not a country that has come about through civil war or a lot of fighting internally..."

Well, probably everyone knew what he meant, even his disingenuous critic, Michael Cullen, who accused him of ignorance of the land wars of the 1860s. But Mr Key did not help himself when he replied: "I'm not naive about the land wars - of course there were musket wars and the like. I was asked a question about the Treaty and that happened after the Treaty was signed."

Why that reference to the musket wars, the inter-tribal conflict that raged during the 20 years before colonisation? The ellipsis had nothing to do with his point and leaves us to presume that he did not mean to say it.

I never thought I'd agree with a Herald editorial - well, not apart from the time the paper called for the sacking of John Bracewell, anyway - but the organ of the Auckland oligarchy is spot on when it faults Key for confusing the Musket Wars with the New Zealand Wars. The New Zealand Wars - also often called The Maori Wars or The Land Wars - are usually said to have begun in 1845, when Hone Heke took on the British in the Bay of Islands, and ended in 1872, when Te Kooti led an exhausted band of guerrillas into the safe territory of the King Country, where the Crown forces that had been pursuing him chose not to venture. Many scholars footnote their discussions of the Wars with references to the 'Dog Tax War' of 1898, which saw armed conflict averted at the last moment in the Hokianga, and the violent Crown raid on Rua Kenana and his followers at Maungapohatu in 1916.

The New Zealand Wars were a complicated series of conflicts fought by a shifting ensemble of iwi, British and local Pakeha forces. The driving force behind the Wars was the contest over land and resources by Pakeha and Maori, but many iwi fought with the Crown for historical and practical reasons of their own, and a few Pakeha sided with Maori.

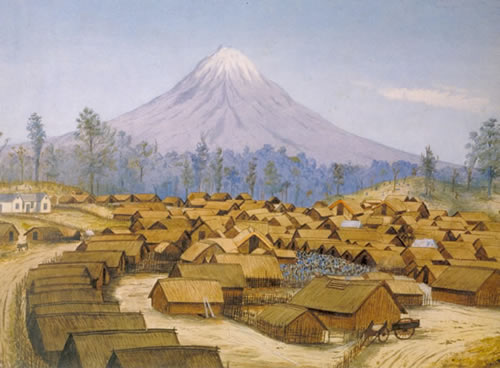

The biggest wars were fought in the Waikato in 1863-64, where a British force of twelve thousand pushed King Tawhiao and his folowers off some of the country's best agricultural land, and in the Taranaki during 1868 and 1869, when the brilliant Maori commander Titokowaru repeatedly routed Crown forces before his own army mysteriously dissolved.

The biggest wars were fought in the Waikato in 1863-64, where a British force of twelve thousand pushed King Tawhiao and his folowers off some of the country's best agricultural land, and in the Taranaki during 1868 and 1869, when the brilliant Maori commander Titokowaru repeatedly routed Crown forces before his own army mysteriously dissolved. If the New Zealand Wars were fundamentally a Pakeha-Maori conflict, the Musket Wars pitted iwi against iwi, and featured little direct Pakeha participation. The Wars, which began in the first decade of the nineteenth century and dragged on until the late 1830s, were made possible by the economic and technological changes that Europeans brought to Aotearoa in the late eighteenth century. The struggle by iwi to produce potatoes, pigs and other commodities in large quantities for new domestic and export markets led to a greatly increased need for land and slaves; the availability of muskets on a large scale gave fighting a new ferocity.

The Nga Puhi chief Hongi Hika remains a bitterly controversial figure amongst many Maori, but he undeniably dominates the story of the Musket Wars. Early in the nineteenth century Hongi befriended the Anglican missionary Thomas Kendall, who took the warrior on a trip to England, in the hope that he might convert wholeheartedly to Christianity. Hongi was bored by St Pauls Cathedral, but greatly excited by a visit to the Royal Armoury. He returned from his OE with a fine supply of muskets, which he used in a series of raids on parts of the country where guns were still a rumour.

The Musket Wars petered out about the time of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, after displacing and decimating many iwi. A tragic sidelight of the Wars was the invasion of the Chatham Islands by two Taranaki iwi, Ngati Mutunga and Ngati Tama, who enslaved the Moriori people that had lived there for many centuries. The Maori newcomers used Moriori labour to establish a pig and potato farming business that fed Wellington (aka Port Nicholson) for years.

It should be evident, even from those short summaries, that the Musket Wars and the New Zealand Wars were two very distinct sets of conflicts. One was fought before the Treaty of Waitangi, between different iwi; the other followed the signing of the Treaty, and was fundamentally a conflict between settler and Maori. By assimilating the Musket Wars to the New Zealand Wars, John Key has confused two radically different parts of our history.

To get a sense of the magnitude of the historical misunderstanding reflected in Key's conflation, let's imagine that Barack Obama was challenged by John McCain to give his opinion of the Vietnam War, and chose to respond by talking at length about the Americans who died at Pearl Harbour and on the beaches of Normandy. Bush's worst gaffe would pale in comparison, and Obama would be laughed out of the US Presidential election. The lack of response by New Zealanders to Key's confusion of the Musket and the New Zealand Wars says a great deal about the lack of historical awareness of large parts of our population.

I find it particularly instructive that the slavering hounds of the pro-Labour blogosphere have completely ignored the rich morsel Key threw them days ago. How is it that they can find time to criticise the architecture of Key's beach house, yet not notice when the man confuses two completely different wars fought on the soil of the country he wants to lead? I suspect that the authors of The Standard and other pro-Labour blogs share Key's encyclopaedic ignorance of New Zealand history. These sites are not really interested in exploring and debating the dense and ambiguous history of inter-iwi conflict and Maori-Pakeha relations in the nineteenth century: they merely want to invoke a simplified version of that history to score cheap political points in an election year. Their attitude to the past is completely instrumental. History is a card they may hold onto or play, according to political exigency. What else can be expected, from supporters of the party which sacrificed its brown support on the altar of the redneck vote with that very nineteenth century piece of legislation, the Foreshore and Seabed Act?

The No Right Turn blog has been another very strong critic of the speech John Key gave at Wanganui last week. No Right Turn is work of a single, 'irredeemably liberal' blogger called Idiot/Savant, and it pushes a political line which is well to the left of that of The Standard and the Labour government.

Idiot/Savant exemplifies both the strengths and the weaknesses of a lot of liberal Kiwi bloggers. He is prodigously productive, churning out several posts a day. He makes passionate cases for civil rights, opposition to US foreign policy, the strengthening of the welfare state, and other causes that should be dear to every heart that beats on the left. But there is little in the way of interesting analysis on his blog: most of his posts seem to recycle news items found in the mainstream media and add a few ejaculations of moral outrage. Idiot/Savant seems to be so busy scanning the latest news updates that he neglects ever to stand back and analyse his material. Reading No Right Turn is a little like listening to an endless series of soundbites.

Over the past few days No Right Turn has thundered righteously about John Key's 'appalling ignorance' of the past, but Idiot/Savant hasn't always been averse to taking history lessons from senior figures in the National Party. Back in March 2004 he posted enthusiastically about former National Cabinet Minister Simon Upton's views on the teaching of Kiwi history:

The latest edition of Upton-on-line compares the teaching of history in France and New Zealand - and the result is unfavourable. French schoolchildren receive a solid grounding in their (idealised, sanitised, propagandised) national story; in New Zealand, it is left almost entirely to chance...

One of the reasons for this is probably because New Zealand history is a) short, and b) fairly boring. Maori settlement, five hundred years of low-tech existence, Captain Cook, European settlement and the Treaty, then (once Maori had conveniently disappeared from the narrative, exiled to the back blocks after their land had been seized) the smooth progression of a socially innovative liberal democracy...

After Idiot/Savant posted these words, I sent him a rather grumpy e mail pointing out that events like the Waikato War could hardly be fitted into his narrative of boring progress, and asking how much reading he had done before he had passed judgement on New Zealand history. I didn't get a reply, but Idiot/Savant did provide some evidence of the depth of his scholarship in a post he made a few months later:

I'd never had the inclination to read much NZ history but I got given the Penguin History of New Zealand for my birthday...after some determined reading I knocked the bastard off...Up until now my knowledge of New Zealand history has had more holes in it than a National Party press release...I've always been happy to read dusty old tomes about other countries' history especially if the country had a decent history of violence to attract my interest.

Michael King had a gift for writing clearly and entertainingly about complicated subjects, and his Penguin History is a generally good introduction to our country's past, even if it is far more partisan than its author pretended (the book's dismissal of the revolutionary character of the Great Strike of 1913, for instance, tells us little about the history of that year and a great deal about King's Blairite politics). It is hard to see, though, how slogging through King's survey could give Idiot/Savant the authority to make his sweeping judgements about New Zealand history.

Admittedly, Idiot/Savant seems to find Kiwi history less boring these days, and his attacks on Key's ignorance are sincere. Too often, though, a shaky grasp of the past means his attacks miss their target. In a new post called 'Digging a Deeper Hole', for instance, Idiot/Savant suggests that Key should tell his feel good version of Kiwi history to 'the people the settler government murdered at Parihaka'.

Admittedly, Idiot/Savant seems to find Kiwi history less boring these days, and his attacks on Key's ignorance are sincere. Too often, though, a shaky grasp of the past means his attacks miss their target. In a new post called 'Digging a Deeper Hole', for instance, Idiot/Savant suggests that Key should tell his feel good version of Kiwi history to 'the people the settler government murdered at Parihaka'. It is quite reasonable for Idiot/Savant to refer Key to the invasion of the thriving Maori community of Parihaka in November 1881. There was little evidence of the goodwill Key claims for early New Zealand governments when Native Minister John Bryce's Armed Constabulary rampaged through the largest Maori settlement in the country, burning whare and plundering pataka. But nobody was murdered at Parihaka: the peaceful resistance which the community so famously offered to the invaders made killing unnecessary. This fact does not in any way detract from the injustice of the invasion of Parihaka, but it does detract from the credibility of Idiot/Savant's argument. Like The Standard, Idiot/Savant seems to think that rhetoric can be a substitute for historical research. John Key is not the only one digging a hole for himself.