He's at it again

Back at the beginning of the year I chided the Women's Bookshop for promoting Gavin Menzies' exercise in pseudohistory 1421: the Chinese Discovery of the World. In his book, which began life as a novel, Menzies asserted that a fleet of massive fifteenth century Chinese sailing boats circumnavigated the world, discovering lands and founding civilisations as they went. New Zealand had a bit part in Menzies' fantasy, as a southern staging post on the epic journey of the Chinese fleet. According to Menzies, Maori are descended from fifteenth century Chinese visitors, and the wrecks of junks are scattered up and down the New Zealand coast.

Back at the beginning of the year I chided the Women's Bookshop for promoting Gavin Menzies' exercise in pseudohistory 1421: the Chinese Discovery of the World. In his book, which began life as a novel, Menzies asserted that a fleet of massive fifteenth century Chinese sailing boats circumnavigated the world, discovering lands and founding civilisations as they went. New Zealand had a bit part in Menzies' fantasy, as a southern staging post on the epic journey of the Chinese fleet. According to Menzies, Maori are descended from fifteenth century Chinese visitors, and the wrecks of junks are scattered up and down the New Zealand coast. The rise of China as a twenty-first century superpower and the gimmicks of the same publishing company that gave us The Da Vinci Code made 1421 commercially successful, but the book was scorned by every scholar who reviewed it. Critics pointed out that Menzies couldn't read Mandarin, and thus didn't notice that the 'ancient maps' in his book were written in modern script; they also wondered why no memory of the Chinese fleet survived in the places it supposedly visited.

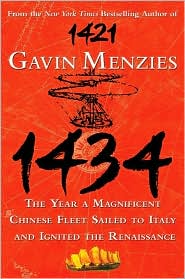

Undeterred by such petty objections, Menzies is ploughing ahead with 1434: the Year a Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance, which the Woman's Bookshop is promoting as 'a stunning reappraisal of history'. The book argues that the Chinese fleet popped in to Italy and dropped off a Chinese encyclopedia, which Leonardo da Vinci and his mates then plagiarised.

I'll leave it to others to slog through and refute Menzies' revision of Renaissance history. What I wanted to comment on, instead, is the total dishonesty of the man's dealings with more serious scholars of the past. When scholars pointed out the implausibility of 1421, he tended to mock them, in terms redolent of the President of the Onehunga Rotary Club, as the fearful guardians of a monolithic academic orthodoxy, and to therefore avoid any serious dialogue.

When he speaks and writes for his large general audience, though, Menzies tries very hard to give the impression that his ramblings enjoy the respect and even the assent of historians, anthropologists, and Sinologists. In 1434, for instance, Menzies lists the names of hundreds of scholars, many of them attached to universities, and thanks them for 'showing interest' in his first book. The type of 'interest' that each of Menzies' interlocutors showed is not, of course, described. Many of Menzies' readers must be in danger of getting the impression that the scholars he lists are supportive of his claims about world history.

Like its predecessor, 1434 drags New Zealand prehistory into its turgid narrative. Menzies claims that his Chinese fleet was on its way home after its triumphant visit to Europe when a massive comet struck the southern ocean, creating a fiery tsunami which washed hundreds of burnt-out junks up on the New Zealand coast. Some of the Chinese survived, and became ancestors of 'the Maoris'. Menzies' 'evidence' for this last claim offers another example of his cynical misuse of the work of serious scholars of history. Menzies claims that biologist Richard Holdaway, who obtained a controversial radiocarbon date for a rat bone found in the Hawkes Bay hill country, and Geoffrey Chambers, who traced Maori DNA back to the vicinity of modern-day Taiwan, have somehow proved that Maori are descended from fifteenth century Chinese. But the bone Holdaway tested came from a Polynesian rat, not the 'Asian rat' Menzies writes about, and it was dated at two thousand years old.

Menzies' invocation of Maori DNA is even sillier: Chambers' tests revealed a connection to South Asia that was five thousand, not five hundred years old. The distant ancestors of the Maori were probably a pre-Chinese people who moved south and east to the western edge of the Pacific, before moving further east to islands like Tonga and Samoa, where Polynesian culture developed slowly over a thousand years. Many Kiwis now understand this story, and are likely to smell a rat when they read Menzies claiming scholarly support for his fairytale, but what about readers in Europe and America, not to mention China?

6 Comments:

Maps why do you think Chinese civilisation is inferior?

" Anonymous said...

Maps why do you think Chinese civilisation is inferior?"

Where do you get this from? I just read what is written here and nothing is mentioned about whether Chinese civilisation is superior or not.

Maps you should delete these really moronic comments - at least my "chocolate face" (cf Borat) comment had some amusing (satirical) aspects ... albeit it was bit silly buggers.

But these guys put The Drivelling Morons & Latter Day Angst Club to shame...

[Unless Maps was drunk and planted the comment himself...hmmm...but it just looks like the comment of a nut case.]

The Chinese 1421 visit to Italy, seems like a screenplay to me.

Hey, how have you been? hope you are well.

Since I left New Zealand in 2006, no memory of me, like the Chinese explorers has survived. :)

Maps is putting China on the maps.

Hi Se Young! Good to hear from you! Do send me an e mail:

shamresearch@yahoo.co.nz

Be good to chat...

Post a Comment

<< Home