Confessions of a bourgeois artist

The Garage Collective, which seems to be a group of left-wing printmakers based in Wellington, has posted a rather unflattering portrait of the New Zealand arts community on indymedia. According to the Collective, Kiwi artists are the servants of the 'bourgeois or corporate class and their markets'. Because we don't call with sufficient enthusiasm for the 'abolishment (sic) of capitalism', we collectively constitute 'a tree that has turned into a club', and we should be 'left to die'.

The Garage Collective, which seems to be a group of left-wing printmakers based in Wellington, has posted a rather unflattering portrait of the New Zealand arts community on indymedia. According to the Collective, Kiwi artists are the servants of the 'bourgeois or corporate class and their markets'. Because we don't call with sufficient enthusiasm for the 'abolishment (sic) of capitalism', we collectively constitute 'a tree that has turned into a club', and we should be 'left to die'. It seems that the Garage Collective means to refer to writers as well as visual artists when they talk about 'art', so I suppose my name would have to figure somewhere on their lengthy blacklist of hopelessly decadent bourgeois artists.

Over the years I've produced a lot of political writing - leaflets, articles, and so on - for various left-wing causes. At the same time, though, I've published poetry in a number of journals, and in a book.

My poems do not argue for the abolition of capitalism, or indeed for any other worthy cause. Nor do the vast majority of the poems, novels, albums, and paintings produced by my friends in different parts of the arts community. Is this evidence for the Garage Collective's argument that we're a bunch of corporate propagandists? If we are, then we're not being paid very well for our propaganda - most of us are broke. And we'd make poor propagandists, even if we were paid well, because most of us have solidly left of centre political views. Although my political views are probably further to the left than most of my peers, my involvement in political activism is not unusual. I run into poets and painters and musicians on all sorts of demonstrations.

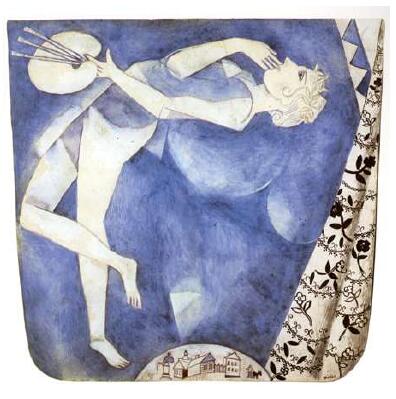

The demand that art take to 'the barricades' by communicating a particular political message is not new on the left. It was the basis of the doctrine of 'socialist realism' which pro-Moscow Communist Parties imposed upon their intellectuals for decades. Party bureaucrats rejected almost all modernist art as 'bourgeois', because painters like Picasso and writers like James Joyce didn't seem to 'take sides' in the class struggle. Party publications featured 'literary pages' which were full of dreary odes to Soviet tractors and Stalin's moustache. I realise that the Garage Collective doesn't advocate Stalinist politics, but they ought to be aware of where the demand for the unification of art and politics can lead.

I believe that art and politics should be kept apart, or at least at arm's length, because good art can achieve things which political discourse cannot. It is not a matter of valuing art over politics, or politics over art, but of recognising that they offer two different ways of thinking and acting.

The hundreds of thousands of New Zealanders who enjoy art in its various forms are not all simply hopeless dupes of capitalism, imbibing the propaganda of the Business Roundtable as they admire a Hotere canvas or read Janet Frame or listen to Miles Davis.

For many of us, art offers a space in which we can escape from the day to day exigencies of life in a twenty-first century capitalist society and enter into a contemplative frame of mind. In this frame of mind we are able to look at our lives and our world from new perspectives, and receive insights we would otherwise miss. Art also helps us to imagine alternatives to the way we live our lives, and to the way our society is organised. It is art's refusal to caught up in the urgency of day to day issues and political sloganeering which makes it so valuable, especially in a society like ours.

With their demand that art be useful - that it get onto 'the barricades' and help promote this or that cause - the Garage Collective actually betray the influence of the ideology of capitalism on their thinking. Capitalism relentlessly instrumentalises both people and things, demanding that they prove that they are 'useful' if they want to survive. In our society, even public hospitals and forest parks have their value 'quantified', and are subject to business 'plans'. The artist who refuses to be 'useful' by creating works that can easily be interpreted and co-opted is taking a far more radical stance than the person who churns out political propaganda.

To say all this is not to argue in favour of 'art for art's sake' or against the idea that art can have political consequences. It is to say that art can be at its most radical and powerful when it refuses to push a political barrow. One of my favourite contemporary New Zealand artists is Brett Graham, who is of Ngati Koroki and Ngati Pakeha descent and frequently addresses the history of colonisation and anti-colonial struggle in his work. I've recently written about Graham's exhibition Campaign Rooms, which is a response to the 2007 police raids on Tuhoe Country that refuses easy political slogans. Graham works on a deeper level than sloganeering can reach, meditating on the conceptual foundations of the colonial state and the symbolism used by that state. He knows the difference between art and propaganda.

I've written at greater length about the idea that art should be radical by avoiding political slogans in this essay, which was published last year in the literary journal brief.

23 Comments:

This is bourgeois.

With their demand that art be useful - that it get onto 'the barricades' and help promote this or that cause - the Garage Collective actually betray the influence of the ideology of capitalism on their thinking. Capitalism relentlessly instrumentalises both people and things, demanding that they prove that they are 'useful' if they want to survive.

Permission to print this on a T-shirt?

Throwing around words like "bourgeois" is at best sloppy thinking. Blogging is bourgeois, as is commenting.

I am reminded of Jean-Paul Sartre's attempts to create a canon of French writers, in which the sole criterion of acceptance was the author's commitment to the cause of proletarian revolution. It was Sartre's contention that only writers who were "engaged" were of value.

Unsurprisingly to anybody but Sartre, this restriction meant that he had a very short list of very bad and deservedly obscure writers. Omitted from his list were the likes of Flaubert, Baudelaire, Zola and all the good writers. So Sartre made exceptions for all these, obviously rather good writers. So, his final list, the canon of French literature, was a list of many "bourgeois" greats and a few "engaged" mediocrities.

Garage Collective is mainly young anarchist Jared G of CHCH..

He has a fair point. Art should say something important or iconoclastic.

If not, it is consumed without challenging anything. Its pleasant fluff.

I think Maps writes stuff that is usually politically engaged, against fascists for example. Sometimes its quite subtle so its politics are not always obvious.

Most good writers are questioning aspects of society. The last novel I read was Toni Morrison's A Mercy about the enslavement of the mind. Same argument as Fanon, but not so obvious. I remember Fanon better.

I am currently reading Musicophilia which documents the amazing impact of music on our brains. Wow, no wonder Lenin refused to listen to Beethoven because it diverted him from the revolution.

So, what does the Fifth Symphony say? And is it inferior to the Ninth Symphony, which has an explicit, sung, political message? Answer on one side of the paper, please.

Art can be political but there is no good reason why it must be so. Perhaps Maps sometimes writes without political intent, which is why the politics of some of his writing seems elusive: it is not there.

The trouble with political art is that it is often crashingly dull, and the political artists who produce it are often crashing bores. Besides, after a few centuries the politics of a work of art is largely irrelevant. One does not need to have an opinion about the outcome of the Battle of San Romano to be able to appreciate Paolo Uccello's paintings of it.

Nor need a work of art "challenge" the viewer to be worthwhile. Aesthetic experiences are generally pleasurable; otherwise we would not seek them.

Yes, Paul, and besides, tell you what: as soon as somebody from Garage whatever produces a work as powerful and counsciousness raising as Guernica by that notoriously apolitical bourgeois artist, Picasso, I'll drop everything else and join them.

Everything is bourgeois - Stalin's moestache was bourgoeis.

Mandelstam had something to say about Stalin's moustache:

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.com/2006/02/kremlin-mountaineer.html

Crikey, I went to look up that Mandelstam poem, which I posted years ago, because I remembered that it contained a description of Stalin's moustache, and I discovered that a rather right-wing Jewish blog has linked to my Mandelstam post as part of its attempt to suggest that Obama is some sort of successor to Stalin!

http://www.keshertalk.com/archives/2008/11/the_white_house.php

I really doubt whether the internet is doing much to improve political discourse...

"Blogger Paul said...

Throwing around words like "bourgeois" is at best sloppy thinking. Blogging is bourgeois, as is commenting.

I am reminded of Jean-Paul "Sartre's attempts to create a canon of French writers, in which the sole criterion of acceptance was the author's commitment to the cause of proletarian revolution. It was Sartre's contention that only writers who were "engaged" were of value.

Unsurprisingly to anybody but Sartre, this restriction meant that he had a very short list of very bad and deservedly obscure writers. "

I agree - this (action of Sartre - a writer who interests me a lot - I love his 'Nausea') - is in itself actually "anti-progessive" (however "progressive" is defined)... and the cannons formed of some great proselytizers such as Greenberg and say Harold Bloom in letters - are very much open to massive debate...who canonizes the canon? Who should we include? Should we have such lists?

many of the "great" writers are very right of centre (some were or are fascists or supporters of similar ideas to the Nazis to differing degrees - these are left wing in differing degrees - some either are or seem indifferent ) - we are all inside the capitalist system - politics in some form is almost always there in art or literature or whatever - but it is the way we approach these things and there are those who - rightly or wrongly - simply ignore politics altogether...

And there is a case to be made that some Art transcends politics of any kind - though it is hard one to argue.

I like Balzac's work but he was not left - I like Hugo - he was quite left - Joyce is or was of the people but hardly really left - Pound was all but a fascist, Knut Hamsun and Heidegger somewhat also - as to artists (I don't like to separate the various arts too much (& there is also film)) ...there are many. Hans Haacke is conceptual political artist - there are many. Hone Tuwhare was Communist... Curnow? Not sure if he had any overt politics... other contemporary NZ poets and artists tend - overall - to be 'left' but some maybe quite right wing...these things don't fit into neat holes. Nor do political (human/social/psychological) etc issues.

Art and poetry like things such as sport or chess or music or things that are ostensibly non political - like beautiful music or sounds can unite us at a basal level of our being - we can - not always - but for a time - ignore "reality" and think of what we are and what others are; and in this way great art of whatever kind speaks to what we are - to what we all are - potentially and - many of very different "classes" or politics or without any apparent politics - can find common areas of experience or unique experience we can commonly relate to as in Ungaretti's poems written in the First World War where his short poems are often strangely refreshing and deeply moving - even the (as far as I know) 'untranslatable

M'illumino

d'immenso

a famous two line poem ("Mattina"): lines I keep hearing in my mind every day even though my knowledge of Italian is virtually zero)) (as are those of Keith Douglas who actually 'liked' war (the Second World War) but created some very beautiful poetry despite or because of the war and his experiences in it or around it...) despite no doubt the horror they (Unagaretti and Douglas - in different times and in different wars) was inside or close to. Here is another poem by Ungaretti

Another Night

(April 1917)

In this dark

with frozen hands

I make out

my face

I see myself

adrift in infinite space

Paul

It would be not right (quite) to say that Map's poetry is (all of it) nonpolitical - yes most isn't overtly political - but there is often a political-historical force at work as in some of the most 'abstract' work there is an emotional force perhaps be 'behind' or energising the creative work ...

But some work - some art - seems to totally transcend politics.

Maps - yes -there is so much nonsense -noise? on the net - perhaps I add to it...!

But it is still a deep truth that without Hitler's and Stalin's moestaches - the universe would collapse!

There is evidence that different coal beds are older/younger than others and various seams have been affected by plate tectonics.

This shows that the earth is 4,000 years old.

Satanists like Richard Taylor disagree.

Reuben

Maps is too hard on young Jared Garage.

I don't think Jared is unconsciously reproducing capitalist ideology but consciously rejecting it. He is calling forth a socialist conception of use (as a value) quite different from capitalist use-value as associated with exchange value. It is to see art as an act to willfully destroy alienation by destroying its causes. It is the spanner in the works.

I think that Lenin avoided listening to Beethoven because Beethoven packaged his subliminal bourgeois "free individual" message in music that caused Lenin's synapses to throb.

He could have dismissed Beethoven's childish romanticism with a short verbal tirade, but he couldnt dodge the synaptic explosions.

Because art (as beauty) mobilises our brain chemistry involuntarily that is no reason to ignore the political values charged by it.

You can hardly call it a debate. Besides getting my information completely wrong (I'm from Otautahi), you haven't posted my text in full, or my subsequent replies. Instead, I'll post them myself once I reply here (www.indymedia.org.nz).

The fact that two fronts of debate have opened up because of this wee text, and has ruffled a few feathers, illustrates a few points. One: that the call for the end of artistic practice separate from everyday life threatens some who prefer to see culture as something we consume at Te Papa, and not to be actively participated in. Two: that art and politics must somehow be kept separate. And finally, that work exploring possible alternatives to the current exploitative system known as Capitalism is propaganda. I'll try to illustrate the failings of these ideas below.

Firstly, my call on 'celebrating dead art' — this is nothing knew. In fact, the name of my text is a blatant reference to a text written by Tony Lowe in the 80's, influenced by Situationist, Dada, and Fluxus art practices (see 'The Assault on Culture' by Stewart Home — AK Press). The idea that art is everyday life, and everyday life is art — therefore breaking down the division of maker and viewer, producer and consumer — is again, an old idea. Nor is it my random musings. There is a huge movement of people engaged in community art projects working to these ends (see www.justseeds.org or 'Art Against Authority' — AK Press). Like I mention above, this prospect must really challenge those who would rather see art or culture as separated from the realities of everyday, working life. As I mention earlier:

"Anarchists have a problem with the seperation of artists from everyday life, and the seperation of art itself from everyday life. Currently art is a thing to be consumed, to be left to an elite few, who through their artistic wisdom and skill allow us to transcend everyday life, and more often than not, to consume culture. We must all participate and have a say in culture if we are to direct its values and concerns. Hence the self-activity proposed (and therefore the abolishment of class division and capitalism). The Situationists went further, proposing that the destruction of a factory, or the throwing of a brick at a cops head, was indeed, art. Like the seperation of politics from our own lives through parliament, artistic practice (and therefore cultural values) are seperated from everyday life by the division of artist and viewer. A goal should be to challenge that."

So, what I proposed was if we can't let the separation of art and everyday life die, then an alternative would be to use artistic action to empower more than oneself, to use it to encourage self-activity and direct control over the cultural process, in tune with our realities under 21st century capitalism. While Scott looks back and decries my definitions when compared to past or current artistic work — I am looking forward, to a new way of working. I am charged with not mentioning names, of not being based in 'artistic reality' — guilty as charged. I have no desire to fluff on about the merits of work that do nothing in ending the exploitation and spectacle of everyday life.

Which leads me to point number two: the separation of art and politics. This is virtually impossible. Nothing is created in a void — all actions, values and intentions are inherently political to some extent. Even to say "I do not make political work' is to take a political stance. Politics is not some removed realm, debated in the great chamber halls of Wellington — personal life is deeply effected by structural and political systems. The personal is the political, and the failure to recognise this fact has resulted in the continuing exploitation and domination by a hegemonic system based on the control of the many, by the few. Hence the need to base art in everyday life, to encourage self-activity, to take direct action, to collectively empower. Again, as I mentioned earlier:

"For anarchists, and anarchist ‘artisits’ (excuse the term), the advocating of radical change through the self-activity of the masses is essential. Therefore it’s not just the message, but the medium which must be empowering. Instead of a particular ideology, we think in terms of self-activity. It’s not a matter of certain slogans, or a correct political message, or art without that correct message as being 'blacklisted'. It's a matter of encouraging direct action, self-activity and empowerment. Does current artistic pratice do that? Some work, as Scott mentions, can provoke thinking and thought, but does it promote further action? Does it deconstruct that mental division of maker and viewer? Sadly, often it doesn’t, and this is the crux of the matter. Radical change = mass self-activity and participation. Art therefore could, and should, encourage this self activity."

This is not propaganda or ideological slandering. I don't wish to take over and control art towards political ends (as Scott compares me to Zhdanov that must be his reading) — I want to open up art to everybody, and to end art as a separate and elite category from our own lives. Art will continue to be elitist as long as 'Wellingtonians are flocking to see Cezanne canvases at Te Papa' and not deconstructing the producer/consumer division so engrained in our social structures.

Above is an understanding of artistic practice quite different to past and current mainstream conceptions — one that deconstructs the privilege of the artist and bases the act of creation back amongst the collective. One that wants to encourage and explore the possibilities of a better world, a world free of exploitation, division and hierarchy. One that would like to see art as egalitarian and meaningful as possible. That conception of art challenges people (and may even piss them off) says a few things louder than this wee text possibly could.

Cheers

Jared D

As I said on indymedia, Jared, I have nothing at all against you and your mates in the Garage Collective producing the type of visual work you enthuse about.

What I object to is your dismissal of the overwhelming majority of artists who are moving to the rhythms of other drums. You can't expect to foster much of a debate when you begin by rejecting every artist who doesn't share your enthusiams as a backward-looking pillar of the establishment.

You talk about 'opening up art to everybody', but you seem to sneer at parts of the art community that don't share your tastes.

You mock those of us who visit Te Papa, for instance, when that institution (despite its manifest flaws) contains some of the greatest masterpieces of New Zealand art. I must be hopelessly bourgeois, but I find it hard to visit Wellington without going to Te Papa see McCahon's Northland Panels, or the magnificient Te Arawa carved storehouse, or the Moriori carvings.

The notion that only a tiny wealthy elite visit art galleries held some truth seventy years ago, but today it is absurd, as the visitor numbers for Te Papa and the Auckland City Galleries show.

There was a long struggle by the arts community and by Maori communities to change the focus of galleries away from conservative, Eurocentric canvases. Maori forced the government to purchase and display works that reflect their culture; avant-garde Pakeha artists succeeded in getting their work into galleries, in the face of misunderstanding and even outrage. Today we should celebrate the collections of our galleries, and defend them from the threat of cost-cutting managers and government underfunding.

(When I say this, I don't mean to imply that art should only exist in galleries. Art can and should find the most diverse locations. I blogged last month about the contemporary dance piece which was performced on a sheep farm, during my civil union!)

I threw an off-the-cuff list of some of the most important artists this country has produced - McCahon, Hotere, Shane Cotton, Rita Angus, and a few others - at you on indymedia, and pointed out that, according to your criteria, none of them would qualify as worthwhile artists. 'So much the worse for them', seems to be your response.

It does seem to me that you don't really understand a great deal about art. You talk of 'opening art up' to people, and letting them participate in art, but great artworks necessarily do that already. Great art is different to political discourse partly because it demands that its viewers complete its meaning, by entering into a sort of mental communion with the artist and interpreting his or her work.

Compare one of the posters reproduced on your blog with a painting by, say, Cezanne. Whereas the meaning of the poster is completely unambiguous - capable, in other words, of only one correct interpretation - a Cezanne canvas cannot be interpreted 'rightly' or 'wrongly' in strict terms. It is designed to stimulate the imagination of the viewer, and to force him or her to enter into its world. It is an invitation to an encounter, not a lecture. Cezanne retains his force, and attracts millions of viewers, long after almost all the political propagandists of his day have ceased to interest anyone beyond historians.

When I say this I am not criticising the posters on your blog - they like well-executed, necessary pieces of propaganda. I'm pleased that they exist. I'm also pleased, though, that there are so many artists in New Zealand who are following in the footsteps of old bourgeois ratbags like Cezanne.

Maps - Jared - I see some good points made by Jared on Indymededia. I commented there - I don't want myself to exclude Te Papa either - not that I have ever been there...

I in fact I am one of those very unlikely to ever afford to buy any work of art (I mean if we are talking galleries) - I did buy one thing once from Czeckoslovakia - but that was only a few hundred dollars - I certainly haven't got even $50 for art work these days...

The "art scene" I would say is generally rather alien - even intimidating - for many working class people or "ordinary people" shall we say...

Jarad is making some good points - but don't throw out the baby with the bath water!

Thanks Scott,

I still disagree that visiting a gallery to view and contemplate work is full participation. In this sense, those who do make work to show in Te Papa, are a minority. Elitist? depends on your viewpoint I guess.

"You talk of 'opening art up' to people, and letting them participate in art, but great artworks necessarily do that already."

I disagree. Its like saying voting once every three years is a valid way of participation. Simply looking at work and contemplating ideas does not encourage the direct democracy of active participation. This is the matter, when you come down to it. I view participation to its most full and direct sense.

I do not mock people at all, so please don't say I do. I am talking from my own perspective, and do not hold a grudge towards other practices — they simply do not interest me.

Thanks for the ongoing discussion.

Jared D

sounds like jared just doesn't like 99.9% art. why does he have to make such a big fuss about being a philistine. nobody's forcing him to go to art galleries.

I think Jared likes art - and he is making valid points.

This makes sense -

"...It’s not a matter of certain slogans, or a correct political message, or art without that correct message as being 'blacklisted'. It's a matter of encouraging direct action, self-activity and empowerment. Does current artistic practice do that? Some work, as Scott mentions, can provoke thinking and thought, but does it promote further action? Does it deconstruct that mental division of maker and viewer? Sadly, often it doesn’t, and this is the crux of the matter. Radical change = mass self-activity and participation. Art therefore could, and should, encourage this self activity."

The point is that a lot of art does nothing - one objection is Auden's who said - poetry (art) makes nothing happen -now if one is not a Marxist or an Anarchist etc then art for arts sake etc is o.k...

(personally I feel it is all more complex - I take some of what Jarad is saying and some of Scott's views) - but the question is how - in reality - Jarad proposes this new art be organised or developed...this is the crunch - but this is not to disparage the idealism and enthusiasm he has.

And in principle, and on reflection, I agree wit this by Jared -

"It's a matter of encouraging direct action, self-activity and empowerment. Does current artistic practice do that? Some work, as Scott mentions, can provoke thinking and thought, but does it promote further action? Does it deconstruct that mental division of maker and viewer? Sadly, often it doesn’t, and this is the crux of the matter. Radical change = mass self-activity and participation. Art therefore could, and should, encourage this self activity."

The point here does art leave us passive or do we act? -

I think a lot does perhaps more than Jarad thinks but a lot of it is dross (expensive) to be hung on walls when guests arrive at the million dollar mansion - rarely do they sit around with their wine and so on in their huge rooms admiring poems as poems can reproduced massively - but art (paintings, installations, sculpture conceptual etc) - is much harder to copy and of more value in $ terms - art of whatever kind - that said

There is a huge range of art. I myself am open to it -I know that is has made many dealers rich - but so be it - that is life...

My feeling is that the art gallery world that I have experienced is not empowering - it is elitist in many ways and not only that - it is for the very rich...

Even the artist Graham with political protest - while good - don't forget the huge sums he will want for his works - now I went to that gallery and the art there on the walls (while fascinating) was massively outside my - and probably most working class peoples' means.

It was interesting indeed - but for $35,000 - well my car cost me $900 and I too about 10 months to pay it off - rarely in my life have I had $35,000 - and now some art is sold for millions.

Jarad has some good points - the words or terms I object to are "should" - there are no "shoulds" - people need freedom and this anarchist groups wil also start a new hierarchy - these always develop..and will probably secretly hoard art while telling the inferior members how bad art is...

Re-read 1984 - let's get a bit cynical here. Jarad does have some good points though... but as to Beethoven he was revolutionary - and he acted for himself a lot - he was courageous for his times and his music is powerful and in no way "bourgeois" - his Fifth Symphony is popular with working people everywhere. (Except the opening bars have been over used now..)

Mozart died a pauper - with about 5 people at his funeral. Schubert was virtually unknown when he died..as was Van Gogh - later people with money (particularly Japanese Capitalists) hoarded his work. Shakespear was a bourgeois - he was a very good (and hard working) businessman and unknown except for a rather ornate long poem he sent to one of the aristocracy..he was known as playwright in London and appreciated by only a few as a poet...(His sonnets were the object of scorn even in his own day - but no the great poetry in his plays...)

So Jarad's impulse is Utopian and one can applaud a young man's zeal...

It's a zeal that makes me a tad uncomfortable, because of all the 'shoulding' that you mention, Richard.

I think there is a perpetual danger for idealistic young men (somehow it always seems to be men!) in constructing an 'ideal' model for art, or the working class, or socialism, or life in general, and then judging reality against it. Inevitably, reality is found wanting - and the idealstic young man ends up rather isolated from reality.

I remember sitting in a pub with an enthusiastic young socialist who had just been extolling the virtues of the working class. Suddenly the classic Kiwi drinking song 'Bliss' came on the jukebox, everybody else jumped up - either to dance or to follow the song's advice and 'get yourself another one' - and my pious socialist friend exploded. 'This song shows you why the working class is divided, degenerate, and weak!' he fulminated, before inssiting we finish up our beers and head for the door. I'd have rather stayed for another one!

I'm interested not in constructing models of some 'ideal' art produced by some ideal, revolutionary movement, but in looking at what artists and art communities are doing right now. To me, that's the 'democratic' way of proceeeding. And I think there's some very interesting stuff going on.

It's not only that I think ideal models based on the way art 'should' be are a bad idea - I also think that some of the details of Jared's particular model are misconceived. Take, for instance, the demand that the boundary between the maker and the audience be abolished. I don't think that this idea is either practicable or sensible, because good art is so often a dialogue between its maker and its audience - a dialogue that depends on their differences, as thei similarities.

When I read, say, James Joyce, I am encountering the sensibility of man who grew up in a very different society to mine, had different experiences, and developed a different view of the world. In order to read Joyce properly, I have to open a part of myself up to him and to his world.

On the other hand, I interpret Joyce's work in terms of my own experiences and the world that created them. We have a dialogue or, as Gadamer called it, a 'fusion of horizons'. And one of the great joys of art is the way that it allows us some insight into the ways that people from very different eras and cultures felt and thought. We are enriched when we experience ancient Greece through the poems of Theognis, or nineteenth century France through the paintings of Theognis, or the history of the Tainui people through the sculpture of Brett Graham. Great art very often *relies upon* some sort of difference between maker and viewer/reader. Why, then, is it so 'unfortunate' that this difference has not been abolished, as Jared claims?

your face is bourgeois

Hi Scott,

I'm keen to get your contacts for future ideas! Can you email me at garage.collective(at)gmail.com if your keen? Cheers.

Jared

Post a Comment

<< Home