My journey to Antarctica

Over the past few weeks I have spent large amounts of time in the chipped porcelain bathtub at the back of our house, reading Updike novels and old archaeological reports, groping absent-mindedly for a hairy bar sliver of soap with my left foot, and occasionally turning the hotwater tap with my right foot. By the the time I emerge from the bath my skin is thoroughly wrinkled, so that I am tempted to wander down the road to the local movie theatre and try to get a senior citizen's discount on a ticket to Slumdog Millionaire.

Over the past few weeks I have spent large amounts of time in the chipped porcelain bathtub at the back of our house, reading Updike novels and old archaeological reports, groping absent-mindedly for a hairy bar sliver of soap with my left foot, and occasionally turning the hotwater tap with my right foot. By the the time I emerge from the bath my skin is thoroughly wrinkled, so that I am tempted to wander down the road to the local movie theatre and try to get a senior citizen's discount on a ticket to Slumdog Millionaire. I have an excuse of sorts for my decadent behaviour. Every winter a little of the cold air which blows up from the Southern Ocean squeezes through the pores of my scarred left arm, finds its way to the nerve which was damaged in a car accident a decade ago, and creates thousands of small electric shocks which remind me what a marvellously intricate creation the human body is, and just how many bones, nerves, and muscles my body contains. By taking long baths and using a mild opoid called Tramadol (I like to crack the shiny plastic pills my doctor gives me open, and sprinkle them in bottles of Waikato Draught, but Skyler discourages this practice) I am able to keep the nerves in my arm quiescent.

Tramadol has very few side effects, but it does tend to both disrupt and enhance my sleep when I use it in reasonable quantities. I find it easy to fall asleep under the influence of the drug, but equally easy to wake up. In a typical night under the influence of Tramadol, I might wake one or two hundred times, but each time fall asleep again after only a few seconds.

I'm not sure if it's adequate compensation, but I have always had remarkably vivid dreams under the tutelage of Tramadol. For a long time, this phenomenon puzzled me. Tramadol is a distant relation of opium, but it lacks the potency of the drug which gave Thomas de Quincey all sorts of 'waking dreams' one hundred and eighty years ago. Tramadol doesn't enjoy the devoted fan base that opiates like heroin, methadone, and morphine enjoy today: not many people are prepared to hold up dairies or forge cheques on behalf of the drug.

I've decided that the vividness of the dreams which Tramadol creates is an accidental byproduct of its uncanny ability to steer its users in and out of sleep. By regularly waking me, yet not keeping me awake for too long, Tramadol holds me in the early, 'REM' phase of sleep - the phase that is associated with dreaming - for much of the night.

The constant juxtaposition of sleep and wakefulness which I experience under the influence of Tramadol also seems to give me the illusion, at least, of conscious control over aspects of my dreams. I can't write the scripts of the dreams I experience under the influence of Tramadol, but I seem to able to improvise a little, and to stretch certain scenes out for longer than they might have taken.

Over the past few weeks I have been handed a particular dream-script again and again. I've tried to describe the dream in this prose poem:

I am floating to Antarctica in my bathtub. I lean back, and feel the warm water lap against my left armpit, unmatting its hair (before I began this journey I had not bathed for months). I cannot see the glaciers of Cape Adare, or the snub of Erebus, but I know I am headed for Antarctica: the air on my forehead and shoulders has grown steadily colder, and the flocks of skua and petrels have grown thicker and slower (I remember a foghorn, and the anxious excited faces of friends and strangers positioned on the pier). Occasionally an iceberg passes me on its way north to the Indian Ocean, where it will drift for months and slowly disintegrate, like a probe aimed into deep space.

Not wanting to upset the balance of my craft, I grope with one foot for the bar of soap, but it has grown thin and slippery, and my toes only succeed in upturning the rubber duck at the end of the bath. I lean forward and search for the soap with my left hand, causing the front of my craft to dip slightly just as a wave rises to meet it. My feet and ankles are suddenly cool, as a few buckets of the Southern Ocean slop over the bow of the bath. I lean backward slightly, and begin to shovel handfuls of water over both sides of my boat. Tiny puffs of steam rise, as warm water strikes the dark grey swell.

I bail the bathtub for a few minutes, until the water laps below my armpits again, and the craft seems to have stabilised. I lean further back, deciding to forget about the soap and get some sleep, but the water that sits on my chest is cooler now, and salt stings the gash I got the night before my departure (I remember the envelope-sized flags the schoolgirls waved, and the men who flashed cameras and shouted questions, until their charter boat turned back at the Heads).

I am just beginning to enjoy the stinging when something scrapes against the bottom of my bathtub. I sit up quickly, and grasp both sides of my craft to stop it rocking. The bow of the bath bumps against something, and I look up to see a slope of ice and snow rising gently but steadily into the distance, as smooth and clean as porcelain. The scraping grows louder, and I feel something cold enter the soft flesh behind my left knee. The bathwater has turned an odd shade of pink, and I remember the leftover shiraz I mixed with vodka, on the morning of the launch. The grey waves have disappeared, the hull has stopped shaking, and a jagged red-tipped tendril of ice rises out of the disappearing bathwater.

I sit and watch the last of the water gurgle away, leaving my rubber duck beached on the long smudge left by the cake of soap that child threw to me from the pier. Ignoring the pain in my left leg I stand up, step out of the wrecked bath, and begin my trek across Antarctica.

After I read these paragraphs to Skyler, she asked 'But what does it all mean?' She had a point. I feel a certain responsibility for these images, since they have floated like bergs out of the cold waters of my unconscious mind on dozens of occasions over the past few weeks. I'm not sure, though, how to justify the importance that the primitive, reptilian part of my brain evidently gives the ridiculous story of my journey to the white continent in a bathtub. I feel rather slighted, in fact. Why do my adventures have to be so quixotic? Why can't I dream about climbing Mount Everest with Sir Ed Hillary, or flying a spaceship through the rings of Saturn, or riding into Havana on the back of a tank beside Che Guevara?

If I had to guess, I would say that there is a juxtaposition of cosy domesticity and unmanageable wildness which I respond to in the image of the journey to Antarctica in a bathtub. Tomas Transtromer, who still hasn't been sent the flagon of Old Thumper he was awarded after topping of this blog's greatest living writer poll back in 2006, has an early poem which contains these lines:

I went to sleep in my bed

and woke up under the keel.

I went to sleep in my warm bed

and woke up under the keel

at four am, when the bones of the drowned

coldly associate.

These words have fascinated me for a long time, and I quoted them in one of the poems in my first book (thanks Tomas). I live on one of the narrowest points of a narrow island surrounded by a vast and cold ocean. At this time of year storms coalesce and intensify offshore, pounce upon the cosy island, then just as quickly disappear. It's hard to avoid seeing a symbol of the fragility of human existence, and the way that apparent security can turn to danger, in all this - a variation, perhaps, on Bede's famous image of human beings as sparrows flying through out of a stormy night through an opened window into a warm feast-hall, then out again into the storm. Perhaps a similar symbol has been stowed in the absurd story of my journey to Antarctica in a bathtub?

It's not always good, though, to treat an image as a symbol. Apart from Updike and Doug Sutton, my bathtime reading has included Donald Davie, the British nonconformist and literary critic known for his ferocious assaults on Popery and academic poetics. In a defence of Basil Bunting's great poem Briggflatts from the academic 'interpretation industry', Davie lands some big blows:

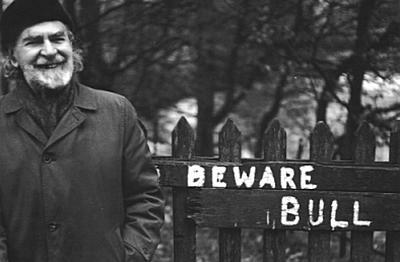

For Bunting, a bull is a bull, a mason a mason, and so on...Rather than let a bull be a bull, and a mason a mason...[the critics ask]that each of them 'stand in for'...some large abstraction like 'life' or 'death'... [for these critics]the variety Bunting honours is unmanageable, and so they rely instead on the postulate of an impoverished reality: that is to say, on the unargued assumption that nature is simpler and less bounteous than she seems. But of course it is possible to believe, as Bunting seems to do, that Nature (human nature included) is just as inexhaustably various, as copiously inventive for good and ill, as she seems to be.

Perhaps, then, my nightly journey to Antarctica needs no elaborate psychological or metaphysical explanation. Perhaps I simply want to explore the white continent. I'll let you know if I get any further inland tonight.

Perhaps, then, my nightly journey to Antarctica needs no elaborate psychological or metaphysical explanation. Perhaps I simply want to explore the white continent. I'll let you know if I get any further inland tonight.

8 Comments:

the fact (if you want to go into symbolism) that you havn't 'bathed for months' before you go on the journey to the 'white lands of Antartica' indicates that you were in a dirty / dark / unwashed state, then you go on a sea voyage (sea = the unconscious) to the whitest landscape in the world, this in alchemical symbolism is where 'the white and black come together in kingly marriage'; the union of opposites, what's interesting is that in alchemy the end result is a red colour, the Red Lion or sulpher - the Philosophers Stone is red because it is alive, with blood in it, so when you rub it, it bleeds, and your dream even has as you reach the ice, the water turning 'pink', a Jungian would have a field day.

BC

Antarctica is not 'all white'.

That is a racist fantasy.

Rod the God

Fascinating. When I was in hospital in 2004 and before the operation on my leg (or it may have been after) they gave me tramadol and paracetamol for pain but tramadol left me feeling a bit queasy. Also I did have a dream, a kind of waking dream. I mentioned it in my Hospital sequence which is a part of my book 'Conversations with a Stone', as you know of course, but other Bloggers on here probably wont):

".....Later I rouse - I took some Tramadol and something else – and talk on and on – about God, fear, love, and nations, and rugby: and nations. The drugs make me talk. I decide to avoid painkillers as much as possible. My foot and ankle area of the lower leg, where the bones snapped...."

Then:

Hospital 6

Wahi Ngaro

the rocks emerging

into men –

the process is terrible,

tyrannical

Hospital 7

Put the Walkman on and played something – cantata. In slipt dream I was King and They had come, were ghostish (various) (suited, some were) gathered in room some by piano...I was their centre till it faded, failed.

The short dream shifts. Am I now awake? The night nurse talks to a an arthritic young man called Garth about his infected leg. Spider Man, Third Man, is asleep, I think. The old man was coughing. I say (in a loudish voice, as if rallying): “How are we team!” I can’t move far with my leg cast so I can’t hold the bugger’s hand. Night is the time of fear. We are visited. The nurse takes my piss bottle. Moves on,returns. My toes wiggle more – more feeling...

__________________________________

Re Briggflats I have a YouTube of Bunting reading from Briggfatts - it is great reading – on my EYELIGHT Blog -

http://richardinfinitex.blogspot.com/

the above link should go straight to my

THE=you=TUBE=POEM

Unlike American and some Kiwi readers of the more recent laid back school of reading - Bunting reads with passion and power. I’m not sure that Davie, who is an astute critic mostly, is completely right about Bunting though. What is his “slow worm” (in Briggflatts) for example? And so on….

Dreams are strange - for me they are rarely very clear – some are. Often they are nightmarish. If one is wakened from a dream it sometimes continues and is usually still vivid…

I noticed strange effects though with tramadol

Doug in the tub? The mind boggles...The real brains were always Yvonne Marshall and Andrew Crosby, but few can hold an audience like Dougal!

There will be no need to ask anyone anything when we join Paul:

http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?book_id=49&chapter=12&version=31

guilt perhaps

heyza

it is a very nice site you have

have a nice weekend

take care

Miracela

I never go to my doctor anymore asking for pain killers prescription and then be turned down at the end, all I do is order online from www.medsheaven.com hassle free and low cost, they have three pain killers listed on their website which are ultram tramadol celebrex that you buy, and the best part is no prescription required!!!

Post a Comment

<< Home