Against space and time: the CROSTOPI Manifesto

TWENTY THESES AGAINST SPACE AND TIME

Issued by the Committee for the Reconstruction of Space and Time on Pig Island (CROSTOPI)

The problems of the anti-traveller

He could not avoid travelling. He sat down in his study and leaned forward in his chair, so that most of his body lay between the four legs of his desk, the beast of burden that would carry his unpublished monograph, the various drafts, the half dozen appendices, on its bent mahogany back for the rest of its days and nights. The piled papers looked like half-finished construction plans for office blocks, he thought, as he leaned forward further, tugged at the curtain, and squinted out the window. The world was a hill and two clouds. He leaned back, and dug the heels of his slippers into the carpet, dug them in hard, so that the creaking of the villa’s uneven floorboards woke the dog that lay like a lumpy old rug beside the fireplace on the western edge of the room. He could not avoid travelling. The world continued to roll at his feet, under his feet, under the overburdened desk, under the Alaska-shaped stain in the carpet that the dog had risen to expose: the earth was carrying him forwards, or perhaps backwards, at a rate of exactly

The discovery of Space and Time, 1857

Karl Marx’s whole body shivers, but his right hand moves calmly, as he hunches, wrapped in a blanket as black and dirty as his beard, over a swaying pool of light, at the city end of his study. The lamp shakes; the whole house shakes, in the third storm of the winter. Marx has not slept properly for a week: he has to keep the right hand moving, he has to get it all down, the whole history that has backed up behind the crisis, like traffic behind an overturned wagon on Tavistock Place. The first great crisis of capitalism – the first and final crisis, perhaps. Marx has moved, in a matter of sentences, from primitive communism, the prehistoric hunter gatherer bands of the humid steppe, to the origins of feudalism, to the transition to the present, precarious system. He can move backwards as quickly as forwards in time. His enemies do not have the same luxury! In the morning, if he can find the change, he will walk to the corner of his street, and buy a copy of The Times, and turn to the business section, and read about the latest bankruptcies, and chuckle at the bourgeois pundits’ explanations for the crisis of overproduction that has left units of special police guarding warehouses of rotting grain and corn.

Marx sits up suddenly in the lamplight. He can feel the world advancing steadily in his direction, across the deserts and market squares and steppes, through winding mine shafts and mill canals, aboard locomotives and steamships and ferries. The annihilation of space by time, he writes, is one of the characteristics of the present age. The world is the London dockyards, plus the reading room of the British Museum. The world is brazil nuts and bananas. The world is a monograph on Gold Coast Religious Beliefs, and a paperback edition of Dante. The world is feather boa hats, absinthe, pig iron, coal slag.

The ouroboros is wasting its time

Marx explained that, like the ouroboros, capitalism could only survive by continually consuming itself. The fixed capital – railway lines, furnaces, dockyards, laboratories – which makes profit possible will eventually become an obstacle to profit, as its features become outmoded, or are replicated more efficiently elsewhere. Capitalism builds spaces, and establishes time-flows, suitable to its needs, and then finds that it must destroy these spaces, interrupt these time flows, as its needs change. The modern becomes archaic. Engineers move out, and preservationists move in. A power station becomes an art gallery. Bohemians squat in old workers’ cottages. A wrecker’s ball swings into a room, ignoring the volumes of Dostoyevsky on the rickety homemade shelf.

The movement of space

Geographer David Harvey has developed Marx’s insights into the changes in space and time created by capitalism. Harvey emphasises that under capitalism space is not so much ‘annihilated’ by time as transformed in a variety of ways. Space is not a static, neutral category: space is in motion, as much as time, space brims at the edges of our maps, or recedes from our theodolite-eyes, depending on its relation to time, and to human behaviour. Harvey uses the term ‘spatio-temporality’ to express the way in which changes in time and in space affect each other. Harvey calls for an ‘anti-capitalist notion of spatio-temporality’ to be added to the arsenal of socialist politics in the twenty-first century. Space and time must be reorganised, along with politics and the economy.

Seasons in flight

Instead of the rhythms of the seasons that dominated agricultural society, capitalist society established a rhythm based around the nine to five working day and the working week. Leisure time and work time alternated. The worker, rose, excreted, showered, breakfasted, commuted, worked, lunched, worked, commuted, ate dinner, fucked, read Hegel or watched television, slept. These were the seasons of Hull, Bruges, Detroit, Otahuhu. With the deindustrialisation of the West and the rise of new, intrusive technology, the old seasons are being eroded. Work creeps into leisure time. She began to consult her blackberry in the adverts, she listened to the answer phone unload itself while she fucked her husband, or read Hegel.

The conquest of time

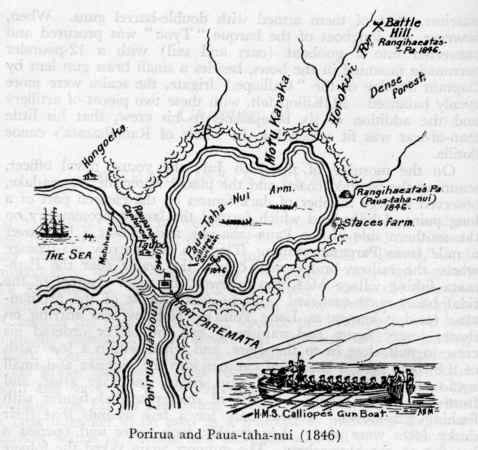

Say that it is July the 11th, 1863, in Auckland, which is still the capital of the discontinuous, incomplete nation of New Zealand. In Auckland, a town of landless settlers reduced to buying food exported north by the Maori tribes they would like to dispossess, the time is measured by the hour, the minute, the second. The invasion of the Waikato Kingdom will begin at six o’clock, on the morning of the twelfth of July, as General Cameron’s army crosses the Mangatawhiri Stream. The protests of friendly natives and confused clergymen are irrelevant: the time has been decided, the signal has been sent, the ironclads on the Waikato River have aimed their cannons at Maori fortifications. And yet the passage of the order from Auckland to General Cameron’s camp at Pokeno, on the northern side of the Mangatawhiri, is compromised, as a horseman bearing the message bogs down in a swamp near Drury, after having to leave a stretch of the Great South Road made dangerous by Maori guerillas, who have been launching ambushes and burning roadside cottages for months.

The Maori struggle against Cameron’s advance to the border of the Waikato Kingdom has been a struggle against the imposition of a certain spatio-temporality. The Great South Road must be destroyed, because it destroys distance. The Pakeha troops must be made to move at the speed of a horse over rough country, or a waka upstream.

The hazards of map reading

Every map has its point of departure in pedagogy. No map is neutral. Medieval maps showed Jerusalem at the centre of the world. The first Maori map showed Hokianga as the centre of the world. The map on the wall of your primary school classroom showed Africa as far smaller than it really is, and put New Zealand at the bottom of the world, when it could just as easily have sat at the top.

Introduced Aliens

Introduced Aliens Cambridge, Morrinsville, Hamilton - the very names of the towns built in the heartland of the vanquished Waikato Kingdom were determinedly alien, were defiantly familiar, for the soldier-settlers and property speculators who established them. The straight lines of the new land blocks, the willows and oaks planted where kahikatea had stood, the well-trimmed hawthorn hedges that stood like lines of troops along the frontier with the King Country, where the Maori rebels still lurked – these were ways of affirming a new culture, a new spatio-temporality. An old culture, an old spatio-temporality.

Adventures in an Official District History

Adventures in an Official District HistoryI stare back at the theodolite, its steady cyclops eye. The surveyor would stand, the surveyor stands, behind the subtle instrument, which he aimed, which he aims, into the middle distance, which has hitherto been nothing but gross, uncharted space, which was, is, space of another order, a land subject to mana whenua, not the Country Records Office, a land awarded to those who use it, those whose placenta are buried under the puriri trees by the sandspit, in the long grass behind the wall of andesite, halfway up Karioi. A land with no bounds was given shape and order, a land of subtle distinctions is replaced by the straight lines of fences and hedges, the tidy stone walls built by young men from Devon and Northumbria, the puriri timber fences thrown up over scum-green wetlands drained like wounds, imposing an order which was a prerequisite for economic development, the low ragged walls which attracted the sunlight, until each lump of scoria was hot to touch, until the kumara swelled through the gravel layer of the plot, without the theodolite and the surveyor’s careful work this colony would still be waste, the history of New Zealand would scarcely

have

begun

Botany and zoology as warfare

Sit in the Auckland Domain, beside the foaming pond where ducks and geese struggle for stale bread, across the road from the banks of colour-coordinated flowers. Next to the bench where you mooch in your trenchcoat, an anaemic Bohemian amongst the flocks of holidaying children and snap-happy tourists, is a small, dirty plaque commemorating the construction of this pond and the nearby gardens by the Auckland Acclimatisation Society, which marshalled its army – its gorse bushes and willow saplings, its blue ducks and Jersey cows – in the Domain, on the eve of the invasion of the Waikato Kingdom. It was these forms of life which would continue the work of the solider, in the decades after the conquest of the Waikato, by occupying and subduing native ecosystems, until the only autochthonous creature in parts of the Hauraki Plains was the eel, which hid deep in the mud of the canals which had drained its old swamp home.

Like Queens Redoubt, the square of raised earth which sheltered Cameron’s army on the evening before it crossed the Mangatawhiri, the Auckland Domain deserves to be classified as an historic military site.

Horology as warfare

The temperature-compensated, mercury-regulated longclock was built in 1869 by AG Bartlett, one of Auckland's first horologists, and is displayed in the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Bartlett's clock recorded the times in London, Wellington, and Auckland with an accuracy unprecedented in the 1860s. The train and the factory required the precise keeping of time, and not only horologists but the new industrial working class had to adjust.

The caption to Bartlett's clock describes it as evidence of the growing establishment of a public time infrastructure in New Zealand. Bartlett's clock was made six years after the invasion of the Waikato, at a time when the vast amounts of land confiscated from Tainui and other iwi were being made available to British-born capitalists. Along with the musket and the theodolite, Bartlett's clock is a charmingly old-fashioned symbol of globalisation.

Into the acid bath

Since it was firmly established by the aftermath of the invasion and conquest of Maori nations in the nineteenth century, New Zealand has gone through several significant spatio-temporal reorderings. After the end of the wars railways were pushed into the hinterlands of both islands, and the market gardening and subsistence economies established by the Maori and by plebian settlers were supplanted by large-scale sheep and dairy operations geared to the demand from markets in Britain.

The expansion of industry after World War Two brought hundreds of thousands of immigrants, most of them Maori, to the city, and for a time New Zealand began to imagine and present itself as an advanced industrial nation, like Sweden or Belgium. Muldoon’s ‘Think Big’ schemes represented the zenith of this tendency, but they became mired in debt, and a section of the capitalist class organised the deindustrialisation and thoroughgoing globalisation of the economy in the second half of the eighties and the early nineties. As Roger Douglas talked of putting the economy through an ‘acid bath’, in the hope that something ‘meaner and leaner’ would emerge, factories were closed, railways were rolled up, and whole towns were closed down.

When the economy eventually rebounded, it did so on the back of agricultural exports and tourism. Both the exporters and the tourism operators had rebranded New Zealand as a ‘clean green paradise’: a virginal land of lakes, forests, and snow-capped mountains. Particularly delectable areas of the country have been cordoned off, cleansed of humans, and described by tourism brochures as ‘unspoilt wilderness’.

Like the Victorian industrialists who expelled crofters from the ‘scenic reserves’ they set up to salve consciences disturbed by the pollution of the Tyne and the Thames, the New Zealand tourism industry cannot imagine the healthy, non-alienated interaction of humans and nature. Wherever there are humans, damage must be done. Small farms must be closed on Stewart Island, where they have operated for generations, or the attempts to rebrand the island as a ‘wilderness’ will fail. Maori must be prevented from harvesting birds and other traditional foods from national parks, for fear that they will ‘spoil’ the forests there.

Artists and writers whose work seems to threaten the new ‘national brand’ are condemned. When he exhibited a photograph of a dead cow lying beside a country road in the nineties, Peter Peryer was called unpatriotic, because of the fear that the image might damage the image of New Zealand’s dairy industry. National Minister John Banks went so far as to call for the repression of the image.

Industrialised wilderness and purified histories

The ‘wildernesses’ established in various corners of New Zealand offer a simulacrum of timelessness to tourists, who arrive by the bus full to wander in eerie goblin forests or stand on majestic mountaintops. But the wilderness is run on industrial time: to walk the Milford Track, one must book a series of huts months in advance, and specify when one’s journey will begin and end. Mountain guides carry cellphones, and charter helicopters to bring down customers who overestimate their reserves of strength.

When human history and culture is allowed to intrude into the ‘clean, green New Zealand’ it must take a sanitised form. Maori culture is exhibited to tourists in a deliberately archaic form, in certain ‘traditional’ areas like Rotorua; scrubbed-up ‘pioneer villages’ are allowed to adorn the old goldfields of central Otago.

Quarantined Zones

Areas of New Zealand which contradict the requirements of the new national ‘brand’ are effectively quarantined: they do not feature on the maps tourists are given, little money is provided to maintain their infrastructure, and their residents are encouraged to move to other, more desirable zones. Time flows through the urban nerve centres of New Zealand into the farms and ‘wildernesses’ at a steady rate, but it falters in the ‘quarantined zones’. Roads turn to potholed gravel there, and cellphones fall silent.

Space-in-reserve

Marx describes the way that capitalism maintains a ‘reserve army of labour’, which can be called up for service if the demand for goods increases, and which in the meantime helps keep the demand for labour, and thus the bargaining power of workers, relatively low.

Capitalism keeps space as well as labour in reserve. Turn off State Highway One at Te Kuiti, climb into the country around Ohura, and admire the eroded hillsides ablaze with gorse. If the demand for dairy products from China redoubles, these hills could yet carry cattle for a few years, until the boom is over. If the price of oil rises very sharply, then the coal that lies under the hills may be worth extracting. If the new prison in the lower Waikato overflows, then this area’s isolation and terrain may be turned to good purpose. In the meantime, the hills and the ancient cottages and corrugated shacks which cling to them persist, as invisible as a shell company.

A List

A Listof ‘quarantined’ areas: the old coal and hydro towns of the King Country, whose residents have refused to move out (in a TV programme dedicated to the woes of this area, economist Gareth Morgan lost his temper and bellowed ‘Mangakino should no longer exist! There is no reason for the place!’, giving voice to a common sentiment in Wellington); the ‘Tuhoe Country’ between Whakatane and Wairoa, whose residents’ denial of the authority of the New Zealand state, refusal to dance in grass skirts for tourists, and desire to clear fell parts of the Urewera National Park terrifies the custodians of ‘brand New Zealand’; the rugged ‘Limestone Country’ between Port Waikato and Raglan, where Maori and Pakeha small hold farmers have resisted the encroachment of the tourism industry and factory farming, and have integrated their families and cultures; the ‘Takimoana Republic’ near the East Cape, where dissident Ngati Porou have attempted to secede from New Zealand; the Whangape and Herekino districts of the far north; the upper Hokianga...

The museum of times and spaces

For a small boy in the 1980s, everything about the Auckland War Memorial Museum - its cold marble walls, its long echoing halls, its interlocking rooms cluttered with dimly-lit exhibits, the half-legible scripts and impossibly long Latin names on the captions under the exhibits - created a sense of displacement. Wandering through the innumerable rooms of the cave, the boy began to understand that there were other worlds - worlds that existed in the past, over the sea, on the other side of my city - radically different to the one he inhabited. The languid gaze of a God's carved head, rescued from a swamp in Northland a century ago; the still bodies of Anzacs on Gallipoli beach; the dry blood on a special policeman's long baton; the fierce grimace of a New Guinea mask: all of these were invitations into new worlds.

A museum’s subversive quality comes from the sense of otherness it induces, and from the traces of different spatio-temporal arrangements it preserves. The commercialisation of museums has gone hand in hand with a faux-populism which has sought to destroy this otherness, and to close the portals to other times and spaces. The dim rooms of the old museum must be replaced with the garish lighting and wide open spaces of the casino, and the artefacts must be mediated by jokey, vernacular captions, or else hidden away and replaced by ‘interactive learning features’ like computer games. Take the Time Warp, and find out you have a lot in common with your ancestors. What would you do if you were Napoleon? Find out why dinosaurs are cool.

A map is a type of museum. As a boy he loved to flip through his grandfather’s old school atlas, to run his hands over the ink-red expanses of the British Empire, to gaze at Africa and wonder at the fragments of liberty (green was the colour of liberty, of recognised independent nations, as distinct from colonies) called Liberia and Abyssinia, fragments almost lost amidst the sprawl of contending European Empires. There were smudged areas, where authorities overlapped (Tangiers, an international city; New Hebrides, a British-French condominium), and there countries which he knew no longer existed (the Kingdom of Siam; Tibet, a British protectorate). Portals.

Against dogmatism

It is not a matter of valourising ‘slow’ time and ‘empty’ space, against the fast time and cluttered landscapes of capitalism, but of supporting spatio-temporal arrangements which favour communities – real communities, not the imagined community of the ‘New Zealand brand’. To support the people of the King Country coast, who demand cellphone coverage so that they can call for an ambulance if they roll their cars on their narrow steep roads, and not be left to die. To support the people of Ngunguru when they campaign against the building of a new, exclusive housing development, complete with a grid of roads, a cellphone tower, and wireless internet coverage, on a peninsula whose open spaces they revere.

A Modest Proposal

We propose mapping the real flows of time and space through the entity variously known as New Zealand, Aotearoa, and Pig Island. We want to create maps which eschew the false objectivity of official cartography in favour of the proliferating realities of personal and collective fantasy. We will map islands, reefs, estuaries, mountain bogs, heresies, tramways, coal shafts, the trajectories of migratory birds and bacilli, the production rates of poets, the death rate of statisticians. It is time for the map to find its proper place in the arsenal of New Zealand artists and poets.

Legend

He loved unfolding the map, loved the way the peninsula extended itself into the squares of empty blue, loved the brushstrokes of pale gray that laid sandbars on the harbour’s shallow bottom, loved the thin mercury-red lines that denoted altitude, the way the knots of terrain between them turned from dark to light green to white, as they closed in on the black triangle that spelt summit. He never wanted to fold the map up again: he was always afraid of turning the sea upside down, of letting it pour over all that land, until it brimmed around the mountains, so that the mountains became mere hills.

31 Comments:

Thanks maps - long live the CROSTOPI Manifesto

Hey Maps you political Pakeha pig when are you going to explain if you will leave hand in your passport eh? Deport the Pakeha, 500k is enough peeps for one country!

PS This arty poetry stuff is shit.

Soon as I get home (am travelling at the moment) I will download & print the Crostopi Manifesto and - relish it. And think about it. Because there's meat, drink & vege therein, and I want to thoroughly digest it all, before commenting-

(unlike some anonymous unfortunates who cannot discriminate their shit from their energised thoughts.

O wait - for them, there probably isnt a difference...)

Maps

Your writing is getting unintelligible old friend. You need to drink less (talk to AA if you need help for your alcoholism) and take your schizophrenia medicine - it will clear your mind. In haste....

fascinating. raising my hand if you need any labour!

Sharply varying responses, I see, which is good!

Anon 1: where am I supposed to go 'home' to?

Anon 2: I'm intrigued by your notion that obscurity is a symptom of schizophrenia. Were Kendrick Smithyman, Wallace Stevens, and Dylan Thomas all schizophrenics? The schizophrenic art which I've looked at - the extraordinary paintings of Richard Dadd, for instance - possess a hyper-real clarity.

And thanks, feddabon, for the offer of assistance. I'm rather conscious of the fact that we haven't actually created any maps yet! The software is made for dummies, but perhaps not for dummies as dumb as me...

Brilliant Maps - it is like a huge poem mixing politics, philosophy, art, space-time etc, the poetical...

I'm convinced anonymous is you - sorry Maps!

But if he or she isn't, then we are talking about one of the biggest wankers God ever shoveled guts up into.

Apart form that - all is well! A great ramble... Ramblelazian in fact...

'I'm convinced anonymous is you - sorry Maps!'

Actually he (why do I assume it is a he?) isn't, though the anonymous comment on your blog is mine!

Either of the anons is invited to elaborate their criticisms in a gueest post. E mail it to me at shamresearch@yahoo.co.nz or put in this box.

@maps: this software...could it get me off my unpleasant dependence on google maps? now i'm the dummy...i didn't even *know there were options, heh.

Cartography as art? Sounds interesting, though i'm not sure I understand entirely to be honest. I'm up to my eyeballs making and analysing maps of Mahinepua at the moment, and I suppose they cover both time and space insofar as they both form the palimpsest i'm trying to understand. (I could email you some of my work sometime if you like, might be good for feedback, but I worry it might be a bit too dry?) But I digress, maps as art is an interesting concept, but one I am unfamiliar with.

Keep us posted.

btw anon, give it a rest would you. Maps isn't a pig, but by the way you keep grunting i'm starting to wonder if you are.

Anonymous is probably John Key or Ian Wedde...

Who is the bloke by the Nic Lookout?

Hi Edward,

I have the highest regard for the maps that adorn archaeological reports, and indeed for many kinds of maps not intended as works of art.

David Harvey's critique of the notion that maps are neutral representations of reality is arguably based on an appreciation that reality is infinitely complex,

continually in flux, and mediated by language and conceputal categories.

For this reason, whenever we think about some aspect of reality we are making an 'abstraction' from a whole which is ungraspable as a whole.

Harvey isn't attacking cartography as a discipline - he is, after all, the world's most influential living geographer - so much as cautioning against the tendency to 'naturalise' abstractions by treating them as unmediated depictions of a self-sufficient reality.

A map of an archaeological site on a Northland peninsula is abstracting a limited space - a square kilometre, say - and a particular duration of time (perhaps the site is pre-European Maori, and the archaeologist is abstracting a period of several centuries).

And, of course, an archaeologists' map is abstracting a particular aspect of the reality

contained within those spatio-temporal parameters - it is focusing, naturally enough, on the traces left by human beings, not on, say, the geology or botany of the place and times it depicts (unless of course these things are essential to an archaeological description of the place and times).

I know this all seems pretty obvious, but with certain types of maps the limitations imposed by abstraction are more easily forgotten. The conventional vertical depiction of New Zealand, for instance, is very commonly thought of as 'natural', and yet it can obscure as much as it reveals.

The Auckland museum has a beautiful map which turns New Zealand 'on its side', and by doing so shows the relations between iwi in a 'new' way. For instance, the map is able to show the continuity of iwi like Ngati Awa and Kai Tahu, which exist on both sides of the Cook and Fouveaux Straits respectively. These bodies of water presented a very considerable challenge to the communications required by an industrial capitalist society, but they were no real impediment to Maori social organisation.

Certainly they were far less of a cultural barrier than the mountains of the central North Island and the Urewera and Raukumara Ranges, which separated Taranaki and Whanganui iwi from groups like Te Whanau a Apanui and Ngati Porou. The barrier that the mountains and forests imposed can be depicted much more easily when New Zealand is 'turned' on its 'side', because this operation reveals the considerable width of Te Ika a Maui.

The maps produced by the tourist industry - think of those cheesey tea towels which used tikis and geysers to represent Rotorua -

are a clear example of the construction of a spatio-temporal reality for commercial purposes.

William Sutton's 'aerial' paintings of the South Island, the young Milan Mrkusich's semi-abstract cityscapes, and Shane Cotton's layered, cartographic Northland landscapes, and the haiku-like poems Richard von Sturmer placed in boxes pasted onto maps of Auckland in the '80s are all evidence that we aren't the first Kiwis to have the idea of making art out of maps. I'm not sure if the map itself has been made into an artform in New Zealand, though. Internationally, psychogeographers have been on the job - Guy Debord's famous map of Paris is a case in point:

http://imaginarymuseum.org/LPG/Mapsitu1.htm

Yes - this is a more complex view of maps. There are many different "projections". I have Bateman's Contemporary Atlas New Zealand - The Shapes of our Nation by Russell Kirkpatrick which has maps of many different aspects of "reality" - physical, cultural, social, historical etc etc and many maps are turned on their side or "distorted" or even upside down or upside the right way... and Smithyman also dealt with certain philosophical issues of maps and space and time and so on.

There's map in the Bateman book intended to show the flows of goods in and out of the port of Lyttleton in (I think) the twentieth century - it shows most of the world, but it puts Lyttleton at the centre, shrinks the continents of North America, Europe and Asia to a fraction of the size of Lyttleton, and makes them orbit the little port town. All in the interests of accuracy.

its interesting to think that in some ways a map is a 2 dimensional representation of a 3 dimensional world. When the depth, that your manifesto explores, is added the map becomes 4 or 5 dimensional - perhaps more, perhaps infinitely dimensional. It reminds me of sci fi chess - you know the star trek one where the board is in more than one plane thus creating multi dimensions.

some say, "the map is not the territory." Maybe the territory is not the map.

Howdy Maps,

I didn't think it was an attack on the use of maps or the discipline of cartography, on the contrary, I think it is important to question these things.

Yes, I agree that these kinds of representations are really absracts of reality. The problem in my experience is unit design and the issue of the 'methodological double blind', which, as Wandsnider says is "the eternal purgatory of scientists". To measure something, we must first know what it is like; but, to know what it is like, we must first measure it.

This bias obviously affects what the end representation might be, so Harvey is quite right to critique the notion of maps as neutral I think. The best we can hope for is to look at something using a number of different methodologies to control for bias as much as possible.

Likewise, your correct about Mahinepua maps being an abstraction. The units I have designed are inherently flawed because they were designed by me, and I have predisposed notions of definition. However, archaeologists have been keenly aware of these issues for some time as they impose directly onto our observations and subsequent inferences of archaeological phenomena.

Lewis Binford highlighted it in the "New archaeology" of the 60's and 70's with his 'middle range theory' which was a way of testing the strength of the linkages between our ideas and the evidence (though buggered if i'm ever gonna be able to read through his treatise on it - the book is huge).

I would point out though that there are many different kinds of archaeological maps. Some focus on the "site" or human activity as you pointed out. Others, such as the method i'm using, focus on the landscape as a whole and take into account geology, soils, wind exposure, topography etc. in order to look at cultural patterning across time and space. Below is an excerpt from my thesis explaining the model i'm using (sorry everyone who is going to be very bored reading this!):

"The methodology employed in this study is that of a landscape analysis approach to the study of settlement patterns and possible site function on Mahinepua Peninsula. The specific quantitative model employed in order to generate this data is a Distributional model, sometimes called a ‘Non-site model’, while a GIS was used for the collation and analysis of the spatially referenced data.

A Distributional model assumes that spatial variation in aspects of all cultural materials is important, and not only the distribution of “clusters” of high density (Banning 2002). Essentially this means that the model assumes that background feature density is zero, and focuses on variation in the density, degree of clustering, and other assemblage parameters over space (Banning 2002:20). Furthermore, the Distribution model used here acknowledges the palimpsest nature of the archaeological landscape, in that archaeological formation processes occur over time and make any pattern that results a cumulative one (for discussion see: Wandsnider 1998; Holdaway and Wandsnider 2008). Over time, repeated discard activity over spaces that satisfy the criteria for settlement, resource procurement, and other human behaviours builds up the density of debris over large areas, while those spaces unsatisfactory for these activities do not accumulate significant densities (Banning 2002:20). As a consequence, even though the resulting clusters of high density anthropogenic features do not necessarily correspond with any specific settlements at any point in the past, they do correspond with preferred locales over some length of time and allow inference as to the environmental resources and other factors which attracted human occupation of those areas (Banning 2002:20)."

The above model is an attempt to minimalise bias by controling the units of measurement by looking at the distribution of everything in relation to everything else. Once this is done, then the more subjective job of making meaning out of the data by way of inference is carried out.

I agree with much of what you've said in the last part of your post. While I do hold that while some things (or kinds of evidence)are quite simply the way they are because of their empirical nature and that no matter how many ways one tries to look at them they stay the same, I do think that alot of it comes down to ways of seeing. A cognitive world of abstraction for the purposes of communication. That aspect in and of itself is worthy of investigation.

Thanks for the info about these ideas in your last paragraphy. I find this topic fascinating.

Ok i'm done. Sorry again for rambling everyone :)

Fascinating, Edward - thanks very much. I will read this carefully and chew it over.

I don't the fact that you have an agenda when you make an abstraction is a negative thing - we have to abstract in order to think, and we have to have some sort of interest in the world and some presuppositions about it in order to abstract. Absolute objectivity is, in my opinion, not only an impossibility but a dangerous ambition.

Marty's comments remind me of Jorge Luis Borges' story about the Empereor who (I think) wanted to create the perfect map of his realm, and ended up creating a map of the exactly the same size as the territory he ruled...

It's worth checking out this site, which is dedicated to collecting the sort of maps that people draw, very casually, every day:

http://handmaps.org/maps.php

These maps are autobiographical, unashamedly subjective, and unashamedly free and easy with geometry. You could lay them on top of the more conventional maps of the places they depict, so that they formed a sort of psychic palimpsest.

'In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.'

Yes Borges is great - Smithyman's poem of this Blogs name is relevant here.

From this it is seen that science cannot exist without other disciplines such as philosophy even literature. Or it is enhanced by these many fields - a map has so many fields - it is always stretching towards the 'truth' but never attaining it - greatly useful but always deceptive; ever more "accurate but ever more treacherously intrusive or impositional...turn maps upside down - or burn them! piss on them! - look at a Mercator projection and the many other...

Screw the map up in rage then smooth it out again.

Look at the map of the consciousness, a map of suffering or joy and palimpsest the map of the "real" word in present and passing time, when the map awakens and beings to breathe and it distorts toward trying to enclose all things, but it is only a model, a mode, a function as in mathematical model with too many variables - impossible to elucidate and as we approach any such exactness we find it all spinning away.

Convulse and regroup. Calculate. Forget and remember. Regroup and redraw.

But we need maps and functions and plots and plans. Or do we, we love them. Or do we... We get used to a a way of saying and ways of seeing. North could have been South or West is toward Europe or Africa NZ or Panmure Waiheke Mongolia might be the centre of all things but a nomad has no centre. And animals no another map, they make their own centres or boundaries. British soldiers had their own maps. Hitler his. Ghengis Kan had a moving map. Maori had or have vastly different maps or ways of seeing. The map is wrapped overall but disintegrates...decays...

Time bursts into flame.

My sister follows maps - she gets lost, it's as if she is moving through abstract space and not engaging. I ignore maps - I seldom get lost. Yep, I do use them as a sort of cosmic, linear view of the world (is that an oxymoron?), but I follow my snoz, mostly. Call it a Bachelardian engagement with my world, as opposed to a Bergsonian onward journey through space.

The idea is advisable to concentrate on the carrier's networks which work immediately while using the maker of this car or truck. Make certain that the business that you decide on features all of the needed certifications for exporting cars in addition to assures secure transport. car exporters

This post was good. You’re going to be a famous blogger. Cheers!

Absolutely a wonderful stories you made here. Cheers for this blog.

I will be sure to read more of this useful magnificent information

Very useful information you shared in this article, nicely written!

Hey! Great information here on this post. Continue writing like this

I’ve enjoyed browsing this blog posts. Hope you write again soon

Post a Comment

<< Home