Is the Pope a Marxist?

Some conservative Catholics are upset about a partly positive appraisal of the thought of Karl Marx that the philospher Georg Sans published recently in the Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano. According to Sans, a devout Catholic who teaches at the Vatican's own Gregorian University, Marx was correct to see that capitalism causes 'social alienation' by allowing 'the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few'. Sans goes on to suggest that Marx cannot be held responsible for the depredations of some of the twentieth century dictators who ruled in his name.

Some conservative Catholics are upset about a partly positive appraisal of the thought of Karl Marx that the philospher Georg Sans published recently in the Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano. According to Sans, a devout Catholic who teaches at the Vatican's own Gregorian University, Marx was correct to see that capitalism causes 'social alienation' by allowing 'the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few'. Sans goes on to suggest that Marx cannot be held responsible for the depredations of some of the twentieth century dictators who ruled in his name. In a response to Sans' text, The Times wonders whether Marx might be about to become the latest intellectual to be rehabilitated by the Vatican:

With reassessments such as [Sans'] it may be wondered which formerly unacceptable figure could be next. Last year the Vatican erected a statue of Galileo as a way of saying sorry for trying the astronomer in 1633 for his observation that the Earth moved around the Sun; in February a leading official declared Darwin’s theory of evolution compatible with the Christian faith, and in July L’Osservatore praised Oscar Wilde, the gay playwright, as “a man who behind a mask of amorality asked himself what was just and what was mistaken”.

Some of the right-wing Catholics who grew up saying prayers for the downfall of communism have had difficulty assimilating Sans' arguments, and have suggested that his article does not in any way reflect the opinions of the Pope. For their part, many left-wing Catholics have responded enthusiastically to Sans' words, hoping that they presage a greater tolerance for progressive trends within the church like liberation theology.

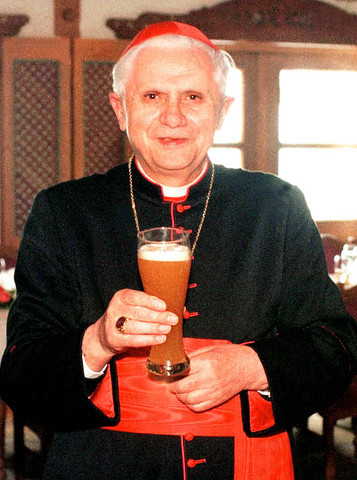

It seems to me that both the conservatives and the left-wingers have misunderstood the reasons for the appearance of Sans' article. The notion that the article sneaked under the radar of censors seems unlikely, given Joseph Ratzinger's reputation for tightly controlling discussion within the official and semi-official organs of his church. It was Ratzinger's zealous pursuit of heresy amongst Catholic intellectuals that earned him the nickname 'God's Rottweiler' during the reign of Pope John Paul the second.

The idea that Ratzinger has suddenly become a supporter of some sort of clerical socialism seems even more unlikely, given his history of defrocking priests who get too involved in worldly matters like strikes and anti-war demonstrations.

The explanation for the appearance of Sans' article may lie in an extraordinary but little-noticed Encyclical which the Pope issued in 2007 called Spe Salvi, or In Hope We Were Saved. Spe Salvi includes a long and surprisingly sophisticated assessment not only of the thought of Marx, but of the whole history of Western thought since the Enlightenment.

According to Ratzinger, Marxism is an extreme example of a wider tendency, visible in the West since the beginning of the Enlightenment, to cast aside the notion that man is a limited being who must be guided by God, and to seek to improve human life through the creation of new technology and the refinement of social organisation. This 'humanist' tendency finds expression in the philosophy of Descartes and Voltaire and the science of Galileo, as well as in the ideas of Marx. By putting humanity at the centre of the universe, and forgetting that what is valuable in humanity comes from God, secularists, rationalists, Marxists, and believers in the ‘invisible hand’ of the free market all set themselves up for disaster. The failures of twentieth century Stalinist regimes flow from Marx's thinking, but they also flow from the hubris of the Enlightenment.

It is useful to contrast Ratzinger's view of these subjects with the interpretation that dominated conservative thinking during the Cold War era. In both its sophisticated version, which was advanced by philosophers like Karl Popper, and its simplistic version, which appealed to tub thumpers like Reagan and Ratzinger's predecessor in the Vatican, this interpretation contrasts the unhealthy tradition of Marxism with the healthy Western traditions of democracy, capitalism, and science. Marxism is a mockery of the Enlightenment, not a logical outcome of the Enlightenment.

It is worth noting that Spe Salvi does not lack a few kind words for Marx. Ratzinger praises Marx's 'great intentions', and also notes his 'acute' understanding of nineteenth century European society. Given that Marx's intentions were always to get rid of capitalism, and given that his commentaries on nineteenth century Europe were full of condemnations of the rapacity of capitalism and imperialism, Ratzinger's words of praise represent quite a departure from conservative orthodoxy. Cold Warriors like Pope John Paul the second tended to depict Marx as a thoroughly evil individual, with a warped understanding of reality.

If we read Georg Sans' article properly, we can see that the interpretation of Marx it advances is very similar to that in Spe Salvi. Sans qualifies his praise for Marx with criticisms of the man's 'materialist' view of the world, which allows no place for the spirit, and warns of an over-confidence in the ability of man and science to solve worldly problems.

It seems, then, that the Vatican has already made a reassessment of Marx, but that the results of this reassessment are more mysterious than either the right or the left of the Catholic church, let alone the media, will allow. How can we explain the peculiar interpretations that Ratzinger has advanced of Marx, and of the Western intellectual tradition since the Enlightenment? If they are not indebted either to left-wing Catholicism or Cold Warrior ideology, where do they come from?

It seems to me that Ratzinger's interpretation of modern Western thought owes a great deal to Martin Heidegger, the controversial German philosopher who cut his teeth as a Catholic critic of modernity before turning against the church, falling in and out of love with Nazism, and retreating, in the last decades of his long life, into a sort of quietism.

Like a lot of conservative, rural Germans, Heidegger was forced into a defensive political posture by the turbulence of early twentieth century Europe and the threat of socialist revolution; unlike his fellow reactionaries, Heidegger traced the chaos around him far back into the intellectual history of his continent. Heidegger believed that the problems of the modern world were rooted in a 'technological' mode of thinking which had gathered strength during the Enlightenment. This type of thinking put humanity at the centre of the universe, and treated nature as a mere 'standing reserve' available for human use. Humans themselves were analysed by 'technological' thinkers like Descartes and Freud as self-contained individuals, when in fact human existence and human consciousness only make sense when they are considered in the context of community, history, and nature. Heidegger explained all of the warring ideologies of the twentieth century - Marxism, social democracy, liberal capitalism, and (after he had recovered from his infatuation with Hitler) fascism - as mere symptoms of the underlying tendency of human beings to think in a 'technological' way.

Heidegger believed that technological thinking stemmed from a 'forgetfulness of being'; in his later work, especially, he tried to practice a meditative thinking, influenced by the arts rather than the sciences, in an effort to recover some of what had been lost. Heidegger's concept of 'being' is deliberately, sometimes infuriatingly, mysterious, and many of his critics have argued that it is simply a substitute for the God that he formally abandoned when he left the Catholic church in his early twenties.

It seems to me that, if the word 'God' were exchanged for the word 'being', then parts of Ratzinger's 2007 Enyclical could have been written by Heidegger. And it is not only in the passages of Spe Salvi that discuss Marx and modern Western thought that we find possible echoes of Heidegger. When he turns from worldly matters to consider the afterlife that awaits faithful Catholics, Ratzinger uses language and imagery which distinguish him from many contemporary religious thinkers:

It seems to me that, if the word 'God' were exchanged for the word 'being', then parts of Ratzinger's 2007 Enyclical could have been written by Heidegger. And it is not only in the passages of Spe Salvi that discuss Marx and modern Western thought that we find possible echoes of Heidegger. When he turns from worldly matters to consider the afterlife that awaits faithful Catholics, Ratzinger uses language and imagery which distinguish him from many contemporary religious thinkers:To continue living for ever — endlessly — appears more like a curse than a gift. Death, admittedly, one would wish to postpone for as long as possible. But to live always, without end—this, all things considered, can only be monotonous and ultimately unbearable...

In some way we want life itself, true life, untouched even by death; yet at the same time we do not know the thing towards which we feel driven. We cannot stop reaching out for it, and yet we know that all we can experience or accomplish is not what we yearn for. This unknown “thing” is the true “hope”...

To imagine ourselves outside the temporality that imprisons us and in some way to sense that eternity is not an unending succession of days in the calendar, but something more like the supreme moment of satisfaction, in which totality embraces us and we embrace totality — this we can only attempt. It would be like plunging into the ocean of infinite love, a moment in which time — the before and after — no longer exists.

Ratzinger's words fly in the face of the tendency of many Christian leaders to describe the afterlife they promise to their followers in decidedly worldly terms. Billy Graham provided a particularly crass example of this tendency when he imagined heaven as a 'place where we cruise along streets paved with gold in our cadillacs'. Even if some of them would cringe at Graham's appeal to materialism, many Christians in the West would share his vision of heaven as a perfected version of the world we know today, not an essentially unimaginable place outside the confines or protections of temporality where we lose not only our worldly desire but our very selves.

Ratzinger's understanding (or deliberate refusal of an understanding) of the afterlife looks back to the tradition of negative theology established in the early centuries of the church by the likes of Pseudo-Dionysus, and developed in the Middle Ages by mystics like the anonymous English author of The Cloud of Unknowing. Negative theology opposes attempts to 'prove' God through reason and argument, and considers the idea that God can even be described in human language and imagery as sacrilegious. As the lecherous but brilliant professor of negative theology who is the anti-hero of John Updike's novel Roger's Version asks, why believe in a God you can understand?

Along with the theologian Karl Barth, Martin Heidegger has been the great modern scholar of negative theology, and it is easy to imagine Ratzinger's description of the ineffability of the afterlife coming from one of Heidegger's more gnomic texts. Ratzinger's insistence on the centrality of death to human existence, and on the worthlessness of life without death, might also remind us Heidegger's famous early work Being and Time, which argued that the humans who ignored the inevitability of their deaths live inauthentic lives.

Despite the obscurity of his prose and the diabolical political positions he adopted in the 1930s, Heidegger exercised an immense influence over twentieth century European thought, and a sophisticated intellectual like Ratzinger would have encountered texts like Being in Time early in his career.

If Ratzinger has adopted some key Heideggerian ideas, what does this tell us about him? It cannot be denied that Heidegger identified some very negative qualities in the modern world. He was a ferocious critic of the special type of alienation that is part of life in many urbanised nations, he despised the shallowness of consumer culture in capitalist nations, and he was horrified by the damage done to the environment by industrial technology. But Heidegger's wholesale rejection of modernity meant that he was unable to suggest any way of ameliorating the ills that he diagnosed, and he retreated into a quietism that was only punctuated by his brief but horrific flirtation with Nazism. In his last interview, given to the German newspaper Die Spiegel in 1966, Heidegger refused to support any political system, insisting that 'only the coming of a God can save us'.

There is a similar hopelessness implicit in Ratzinger's 2007 Encyclical. Human attempts to improve and transform the world are doomed to failure, because what is valuable in humans comes from God, yet God is, as some of the more metaphysical passages of the Encyclical show, a fundamentally 'unknown thing'. Ratzinger has neither faith in human progress, nor the sort of crass belief in an easily accessible, manipulable God that made the likes of Billy Graham or even Pope John Paul the second such popular figures amongst Western audiences keen for quick-fix theology. Like Heidegger's last interview, Spe Salvi has a sort of bleak integrity, but it should not enthuse either the left or the right wings of the Catholic church.

a.jpg)

_Emma_Smith.jpg)

_Ben_Ou.jpg)