Ratana redux, or a new William Gittos?

The Kaipara blogger known as Mad Bush Farm - her children apparently call her Liz - has made a fascinating response to my post about the old Ratana temple near Ruawai:

The Kaipara blogger known as Mad Bush Farm - her children apparently call her Liz - has made a fascinating response to my post about the old Ratana temple near Ruawai:Last year on my way to Dargaville I stopped to help a local Maori family to get their cattle down part of State Highway 12 from Otuhianga Rd. Minnie the Grandmother knew all about the little church. It seems sure enough that [the Wesleyan] Reverend William Gittos did have a lot to do with that little chapel. According to Minnie the church came from Helensville in 1884...

There is a plan to restore the church - so Minnie had told me - and as I understand it Historic Places Trust is involved has a conservation plan. I intend contacting the Historic Places Trust to see if there is any progress on this. So the little church was originally Wesleyan Methodist...

Liz's comment supports her friend and fellow local historian Timespanner's earlier contention that the building near Ruawai belonged to the Wesleyan movement before it became Ratana, and not to Anglicanism, as I had thought.

In the 1830s Te Uri o Hau, the tangata whenua of the northern Kaipara, invited the Wesleyan church to set up a mission station inside their rohe. Te Uri o Hau had suffered badly from raids made in the 1820s by the Nga Puhi warlord Hongi Hika, and they hoped that the presence of the Wesleyans, who had already established a firm base for their church in the Mangungu district of the southern Hokianga, would help to protect them against further invasions from their well-armed northern neighbours.

In the 1830s Te Uri o Hau, the tangata whenua of the northern Kaipara, invited the Wesleyan church to set up a mission station inside their rohe. Te Uri o Hau had suffered badly from raids made in the 1820s by the Nga Puhi warlord Hongi Hika, and they hoped that the presence of the Wesleyans, who had already established a firm base for their church in the Mangungu district of the southern Hokianga, would help to protect them against further invasions from their well-armed northern neighbours. The Wesleyans opened a mission station on the northern edge of Te Uri o Hau territory in 1836, and gradually began to establish a network of chapels and churches across the northern Kaipara. The Wesleyan expansion reached its zenith during the long reign of William Gittos as head of the church in the northern Kaipara. The missionary, who took up his post in 1856 and relinquished it reluctantly in 1886, insisted on being known as Father Gittos, and saw himself, rather patronisingly, as the father and protector of Te Uri o Hau. He intervened often in the internal affairs of the iwi, and supervised the building of Wesleyan churches on the grounds of marae. A church which rose on the grounds of the large Otamatea marae became known, with his approval, as 'the Cathedral of Gittos'.

Gittos seems to have benefited from the relatively friendly attitude which Te Uri o Hau and its Ngati Whatua cousins in Auckland maintained towards Pakeha. During the early 1860s, when tensions between the Pakeha government in Auckland and the Waikato Kingdom further south were building, and Pakeha feared a Waikato invasion of their capital, Governor George Grey actually tried to persuade Te Uri o Hau to settle en masse in the city to their south, so that they could help to defend it.

In This Valley in the Hills, the ramshackle history of several districts of the northern Kaipara he self-published in 1963, Dick Butler describes a couple of incidents which tell us a good deal about Te Uri o Hau politics and William Gittos' personality. After being taken prisoner at the battle of Rangiriri in 1863, scores of Waikato soldiers were kept in rusty hulks parked off the coast of Kawau Island, where Governor Grey lived when he was not in Auckland. Early in 1865 the prisoners escaped, and made their to the mainland and into the rohe of Te Uri o Hau, where they began to raid the properties of Pakeha settlers for food and tools.

In mid-February the escapees met with Te Uri o Hau leaders at the mouth of the Hoteo river in the central Kaipara. They were received cordially, but the locals refused to join them in launching a rising against the government in Auckland. Te Uri o Hau had remained neutral in the Waikato war, refusing Grey's request to take up arms against the southern 'rebels', and they wanted to remain neutral.

Gittos was in Auckland when he heard about the meeting at Hoteo. Alarmed that 'his' people might be seduced into support for the Waikato, Gittos headed immediately to the docks at Onehunga and boarded a ship bound for the Kaipara harbour. When the ship had reached the entrance to the harbour, its captain decided to pause and wait for a storm which which was blowing to subside. The sandbar at Kaipara heads is one of the most treacherous in New Zealand, and by 1863 it had already claimed the lives of dozens of European sailors and settlers.

Impatient to get home, Gittos paced backward and forward on the tilting deck of the little ship. Finally, unable to wait no longer, he seized the wheel from the captain and steered the craft across the bar himself. After crashing over a couple of huge waves, and seeming for a moment like it might capsize, the ship entered the calm water beyond the bar. Butler quotes a witness as saying that 'the captain was white as a sheet, but William Gottis was perfectly calm'.

By the time Gittos left the northern Kaipara he had become unpopular for his authoritarian ways, and for the shonky land deals he had conducted on behalf of the tribe. Gittos' successors were more liberal, and they encouraged young members of their flock to train as priests and develop a distinctively Maori form of Wesleyanism. One of the young men who went off to Auckland's Wesley College was Paraire Paikea, who was ordained a Minister in 1920. The Wesleyan authorities were proud of Paikea, who had been dux at Wesley, but the young man would soon help to destroy their church's hold on the northern Kaipara.

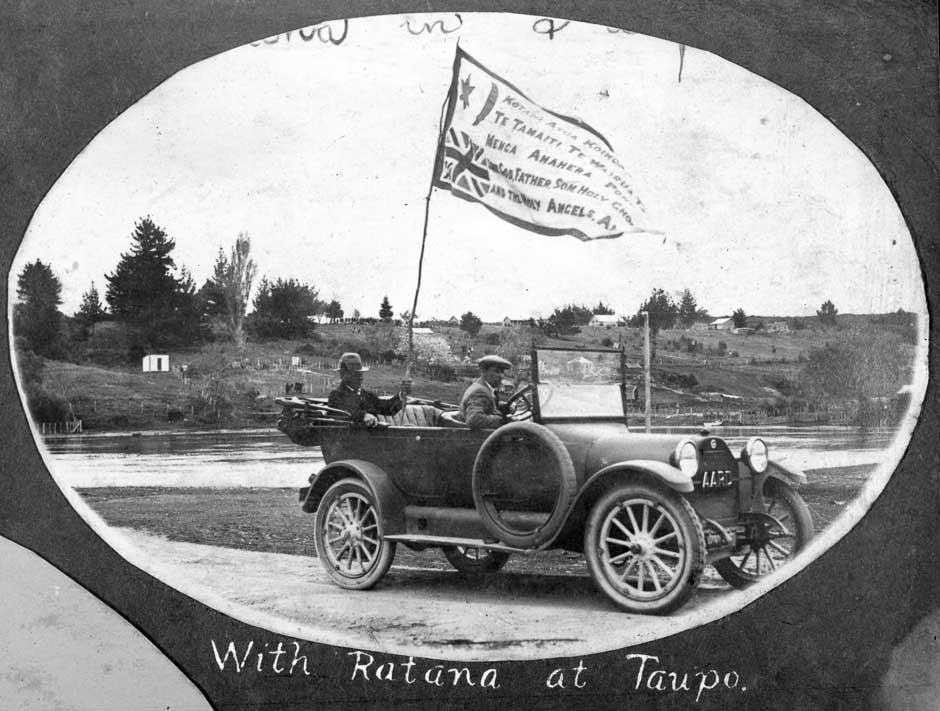

By the beginning of the '20s the loss of land, poverty, and the appalling experience of the Spanish flu pandemic, which had not responded to the prayers of clergy, had combined to weaken the Wesleyan faith in the rohe of Te Uri o Hau. The arrival of the healer and Maori nationalist Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana in the district in 1921 doomed the old faith to irrelevance. Ratana, who was on a national tour designed to attract supporters to his nascent movement, was greeted at the Helensville train station in the southern Kaipara by hundreds of curious locals, and then taken north to Otamatea marae by car.

In the massive study of the Ratana movement he published several years ago, Keith Newman describes how Ratana entered the meeting house at Otamatea and approached an elderly woman named Rahui, who was lying quietly on a mattress on the floor. Rahui had been blind and crippled for years and, in front of hundreds of observers, Ratana attempted to heal her. He lit a match, and asked Rahui if she could see anything. When she whispered 'whetu' (star), Ratana moved the match further from her eye, and asked Rahui if she could see any more. She replied that she could see quite clearly, stood up, and walked out of the house. When they saw what appeared to be a miracle, members of the crowd began to throw themselves on their stomachs and proclaim Ratana's powers.

The Ratana faith soon became strong across the north Kaipara. Paraire Paikea defected from the Wesleyans, and helped to build up a Ratana infrastructure in the area (he would eventually become a Ratana MP, and a member of the wartime Labour government).

The Ratana faith soon became strong across the north Kaipara. Paraire Paikea defected from the Wesleyans, and helped to build up a Ratana infrastructure in the area (he would eventually become a Ratana MP, and a member of the wartime Labour government). Paikea ran into trouble, though, when he attempted to convert the Wesleyan churches that Gittos had built into Ratana temples. Gittos had transferred the ownership of the land on which many of the buildings stood to the Wesleyans, and the church was in no mood to hand it back. At Otamatea and some other marae, Wesleyan churches sat empty, and families who had converted to the Ratana faith were unable to bury their dead in the churchyards where many of their ancestors lay. The little church near Ruawai, which was converted for use by a Ratana congregation, seems to have been an exception to the pattern across the north Kaipara.

Ratana's name has been bandied about in the media in recent days, as commentators grapple with the latest antics of Brain Tamaki, the self-appointed Bishop and 'King' of the Destiny Church. The recent ceremony at which seven hundred male church members took an oath to serve Tamaki unquestioningly, and Tamaki's increasingly bellicose sermons about the 'evil of the world' and the need for 'spiritual war', have led many people to brand Destiny Church as a dangerous cult. Peter Lineham, who teaches at the Albany campus of Massey University and has published widely on Kiwi religious history, has questioned whether Tamaki can be considered a cult leader, and compared him to Ratana and Maori prophetic leaders of the past.

I agreed with Lineham when he made a similar argument back in 2004, but I think the comparison between Tamaki and Ratana has become increasingly difficult to sustain.

There are certainly some parallels between Ratana's movement in its early years and Destiny church. Like the Ratana church, Destiny is overwhelmingly Maori, recruits many poor people from marginalised communities, and relies heavily on a charismatic leader. It seems to me, though, that Tamaki's authoritarianism, increasingly violent language, desire to shield his members from the influence of 'the world', let alone other faiths, and reliance on American rather than Maori models differentiates him from the man who won the support of the people of Otamatea back in 1921.

Ratana's followers were divided over their attitude to Christianity - some, influenced by the nineteenth century nationalist religion of Pai Marire, wanted to banish Ihu Kariti from prayers, and replace him with te mangai from Whanganui, while others wanted the church to be orthodoxly Christian - and after Ratana's death there were efforts to elevate him to semi-divine status. Newman's book shows us, though, that Ratana himself was a surprisingly modest man. Although his reputation as a faith healer and his reputed supernatural experiences meant he was regarded with awe by his followers, he never claimed to be infallible, and he was prepared to admit, late in life, that he made serious mistakes, like drinking too much at times and having an extramarital affair. During Ratana's lifetime, debates about theology and politics were conducted freely within the church he had established. Ratana certainly never sought the unquestioning obedience that King Tamaki demands from his followers.

Ratana's constant attempts to make alliances with other faiths and with political groups to advance the cause of Maori also differentiate him from Tamaki. Ratana never stopped demanding that the Treaty of Waitangi be honoured and that Maori have equal opportunities in their homeland; perceiving the common interests between his impoverished followers and the working class Pakeha who supported the early Labour Party, he formed an alliance with that organisation. Unlike Ratana, Tamaki wants to keep his followers away from involvement with the world outside his church. He is unable to work even with other hardline Christian churches, and the political party he formed a few years ago was a disaster.

Although he took an iconoclastic attitude to some traditional Maori concepts - to the idea of tapu, in particular - Ratana was immersed in Maori religious history. He worked hard to establish himself as the successor to the nineteenth century prophet and guerrilla fighter Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tururki, visiting sacred sites associating with Te Kooti and interpreting predictions made by Te Kooti in such a way that they seemed to refer to him. In the epilogue to her biography of Te Kooti, Judith Binney notes some of the features of the tradition to which Te Kooti and Ratana both belonged:

This religious history...is volatile. It can be constantly rewoven as well as renewed. As a lineage of ideas it is seized upon as a way out of economic or political powerlessness... [It offers] alternative understandings, as the language of allegory and symbol is the language of multivalence of meaning. We who claim to live in an age of signs tend to construct much more narrowly defined messages and forget the infinite variety of shadow and light which is maintained through a language of symbols.

The black and white theology of Brian Tamaki, with its sources in the televangelism of the United States, has little in common with the ambiguous prophetic utterances of Te Kooti and Ratana.

The black and white theology of Brian Tamaki, with its sources in the televangelism of the United States, has little in common with the ambiguous prophetic utterances of Te Kooti and Ratana. Tamaki's violent sermons, and his identification with King David, might seem to link him to the warrior-prophet Te Kooti, who composed karakia and haka inspired by the Psalms of David in his war camps in the forests of the Ureweras. As Binney notes, though, Te Kooti destroyed many of these compositions, as he tried to distance himself from the language of violence during the last decade of his life. In any case, Te Kooti's holy war, which was prompted by persecution and the theft of land, bears little similarity to the crusade that the multi-millionaire King David of Destiny church talks of waging against 'sinners' like feminists and secularists.

It seems to me that, in his authoritarian attitude towards his flock, his intolerance toward other organisations, and his importation of a crass and alien model of religion, Brian Tamaki resembles William Gittos, not Wiremu Ratana. I certainly hope that Tamaki's church will meet the same fate as the cult of personality Gittos strained to establish in the north Kaipara one hundred and fifty years ago.

12 Comments:

http://www.beretta-online.com/wordpress/index.php/brian-tamaki-and-destiny-church-when-cults-fill-the-void/

Do you know brother Brian personally?

Thanks Maps for the mention there. And a fascinating history of Gittos and the Ratana movement.

Just a couple of things. My kids don't call me Liz my friends do and all of the community of Maungaturoto where I live. I edit the local rag in the township so hiding is not an option. I'll just point out on "This Valley in the Hills" Dick Butler compiled the book but a lot of people were involved in getting the research namely the Maungaturoto Centennial Committee. I know one of them as a personal friend. Few are alive now that were involved with the putting together of the research for that book and yes there are some glaring errors. Ramshackle perhaps but it is an excellent reference. 2013 Marks 150 years for Maungaturoto. Hopefully we'll be able to update This Valley in the Hills with an extra 50 years or so of lost history. A monumental task.

Thanks Maps great blog.

Hi Liz,

Perhaps I should have said 'gloriously messy', rather than ramshackle! I certainly found some interesting stuff in the book. I'm pleased to see your blog appears to be back in business, too.

Maps you're good value. Gloriously messy (Valley in the Hills)yes and I have bookmarks with notes all over the place in This Valley in the Hills which Timespanner had kindly brought for me to use as a reference. I have a pile of interesting stuff I've gleaned over the last year or so. Lisa too has taken her own time and trouble to provide me with resources I would otherwise would not have access too. Northland is a goldmine where history is concerned. I'll thank you and Timespanner for the rev up on the blog. Good one Maps I've been enjoying your blog it's excellent.

Alas, Minnie was mistaken about the provenance of this church, which started life as a place of Anglican worship for a group of Te Rarawa, who had migrated to Parirau to find work in the nearby gumfields and forests.

Known as Zion Church, it was the second Anglican church built on this site on Otuhianga Road and its opening is well documented in the Anglican Church Gazette for May 1889:

"Parirau, Kaipara. – New Maori Church. –It is several years ago that the Maories of Parirauewha, Kaipara, commenced collecting funds wherewith to build a new church, their old one having become dilapidated. They are a colony of the Rarawa tribe from Whangape, Herekino, and Ahipara, and as they had to purchase the land they occupy from the European settlers, they have had a hard struggle to acquire the means for attaining their object. By steady exertion they have succeeded, and are now in possession of a house of prayer of which no English community need be ashamed. The building will accommodate 130 worshippers, and is complete in every detail. The cost, with furniture, was £198, and on the evening of the opening day, not only were all the liabilities defrayed, but there was a small balance to credit... As scarcely half of those assembled could find even standing room in the building, seats for 120 persons were extemporised on the shady side, and as the windows were open those outside could join in the hymns and prayers, as well as hear what was said. At 10.30 the service began with ‘The Church’s One Foundation,’ all the clergy taking part, Mr Tobin’s being the second lesson, which he read in Maori quite intelligibly. The Archdeacon read from Eph. v. 8, and contrasted the present with the former condition of the congregation. The offertory collection amounted to £23 8s 10d. By crowding into the vestry and porch, 225 managed to get under the roof, and though many had to stand during the whole service, there was nothing in their conduct which the most fastidious could object to. Many of the settlers, of whom there were at least 100 present, who had no before attended a Maori service, were impressed with their reverent manner and heart responses. Very soon after the service all were invited to a sumptuous dinner, which was laid out in a spacious shed, the table seating 84. As there were 490 to be fed, dinner was going on all afternoon. In order to show the union of the races, the pakeha visitors were ranged on one side of the table, whilst the Maories had the other. Those who have experienced native hospitality need not be told that there was enough and to spare for all. As there were three Maori clergy to conduct the Sunday services, the Archdeacon did not think it necessary for him to remain for that day, and so gladly gave his help to his indefatigable brother clergyman, Mr Tobin, preaching at Matakohe, Paparoa, and Pahi. Mr Tobin’s district is a rough one at the best of times, and how he manages to get through his work in winter is a secret known only to himself and his horse."

The church served the Anglican congregation at Parirau until the 1930s when it was transferred to the Ratana congregation.

It is currently closed for restoration and the local restoration committee is seeking funds for this work. Donations would be gratefully received by:

The Treasurer,

Zion Church Restoration Committee

110 Tana Rd

RD 2 Matakohe 0594

Northland

Alas, Minnie was mistaken about the provenance of this church, which started life as a place of Anglican worship for a group of Te Rarawa, who had migrated to Parirau to find work in the nearby gumfields and forests.

Known as Zion Church, it was the second Anglican church built on this site on Otuhianga Road and its opening is well documented in the Anglican Church Gazette for May 1889:

"Parirau, Kaipara. – New Maori Church. –It is several years ago that the Maories of Parirauewha, Kaipara, commenced collecting funds wherewith to build a new church, their old one having become dilapidated. They are a colony of the Rarawa tribe from Whangape, Herekino, and Ahipara, and as they had to purchase the land they occupy from the European settlers, they have had a hard struggle to acquire the means for attaining their object. By steady exertion they have succeeded, and are now in possession of a house of prayer of which no English community need be ashamed. The building will accommodate 130 worshippers, and is complete in every detail. The cost, with furniture, was £198, and on the evening of the opening day, not only were all the liabilities defrayed, but there was a small balance to credit. ... At 10.30 the service began with ‘The Church’s One Foundation,’ all the clergy taking part, Mr Tobin’s being the second lesson, which he read in Maori quite intelligibly. The Archdeacon read from Eph. v. 8, and contrasted the present with the former condition of the congregation. The offertory collection amounted to £23 8s 10d. By crowding into the vestry and porch, 225 managed to get under the roof, and though many had to stand during the whole service, there was nothing in their conduct which the most fastidious could object to. Many of the settlers, of whom there were at least 100 present, who had no before attended a Maori service, were impressed with their reverent manner and heart responses. Very soon after the service all were invited to a sumptuous dinner, which was laid out in a spacious shed, the table seating 84. As there were 490 to be fed, dinner was going on all afternoon. In order to show the union of the races, the pakeha visitors were ranged on one side of the table, whilst the Maories had the other. Those who have experienced native hospitality need not be told that there was enough and to spare for all. As there were three Maori clergy to conduct the Sunday services, the Archdeacon did not think it necessary for him to remain for that day, and so gladly gave his help to his indefatigable brother clergyman, Mr Tobin, preaching at Matakohe, Paparoa, and Pahi. Mr Tobin’s district is a rough one at the best of times, and how he manages to get through his work in winter is a secret known only to himself and his horse."

The church served the Anglican congregation at Parirau until the 1930s when it was transferred to the Ratana congregation.

It is currently closed for restoration and the local restoration committee is seeking funds for this work. Donations would be gratefully received by:

The Treasurer,

Zion Church Restoration Committee

110 Tana Rd

RD 2 Matakohe 0594

Northland

Alas, Minnie was mistaken about the provenance of this church, which started life as a place of Anglican worship for a group of Te Rarawa, who had migrated to Parirau to find work in the nearby gumfields and forests.

Known as Zion Church, it was the second Anglican church built on this site on Otuhianga Road and its opening is well documented in the Anglican Church Gazette for May 1889:

"Parirau, Kaipara. – New Maori Church. –It is several years ago that the Maories of Parirauewha, Kaipara, commenced collecting funds wherewith to build a new church, their old one having become dilapidated. They are a colony of the Rarawa tribe from Whangape, Herekino, and Ahipara, and as they had to purchase the land they occupy from the European settlers, they have had a hard struggle to acquire the means for attaining their object. By steady exertion they have succeeded, and are now in possession of a house of prayer of which no English community need be ashamed. The building will accommodate 130 worshippers, and is complete in every detail. The cost, with furniture, was £198, and on the evening of the opening day, not only were all the liabilities defrayed, but there was a small balance to credit. ... By crowding into the vestry and porch, 225 managed to get under the roof, and though many had to stand during the whole service, there was nothing in their conduct which the most fastidious could object to. ... Very soon after the service all were invited to a sumptuous dinner, which was laid out in a spacious shed, the table seating 84. As there were 490 to be fed, dinner was going on all afternoon. In order to show the union of the races, the pakeha visitors were ranged on one side of the table, whilst the Maories had the other. Those who have experienced native hospitality need not be told that there was enough and to spare for all..."

The church served the Anglican congregation at Parirau until the 1930s when it was transferred to the Ratana congregation.

It is currently closed for restoration and the local restoration committee is seeking funds for this work. Donations would be gratefully received by:

The Treasurer,

Zion Church Restoration Committee

110 Tana Rd

RD 2 Matakohe 0594

Northland

Alas, Minnie was mistaken about the provenance of this church, which started life as a place of Anglican worship for a group of Te Rarawa, who had migrated to Parirau to find work in the nearby gumfields and forests.

Known as Zion Church, it was the second Anglican church built on this site on Otuhianga Road and its dedication in April 1889 is well documented in the Anglican Church Gazette for May 1889:

"Parirau, Kaipara. – New Maori Church. –It is several years ago that the Maories of Parirauewha, Kaipara, commenced collecting funds wherewith to build a new church, their old one having become dilapidated. They are a colony of the Rarawa tribe from Whangape, Herekino, and Ahipara, and as they had to purchase the land they occupy from the European settlers, they have had a hard struggle to acquire the means for attaining their object. By steady exertion they have succeeded, and are now in possession of a house of prayer of which no English community need be ashamed. The building will accommodate 130 worshippers, and is complete in every detail. The cost, with furniture, was £198, and on the evening of the opening day, not only were all the liabilities defrayed, but there was a small balance to credit..."

The church served the Anglican congregation at Parirau until the 1930s when it was transferred to the Ratana congregation.

It is currently closed for restoration and the local restoration committee is seeking funds for this work. Donations would be gratefully received by:

The Treasurer,

Zion Church Restoration Committee

110 Tana Rd

RD 2 Matakohe 0594

Northland

Apologies for the multiple posts - the blogware kept telling me I'd exceeded the allowable number of characters and that it couldn't accept it - when obviously it had!

Hi Sebastian,

thanks very much for that information, which I will put up as a blog post at the end of the week...

The descedants of Parirauewha are scattered all over the world. The 12 owners of the whenua on which the little Haahi sits are the descendants of the original owner Hohaia Te Ru.

The 12 Owners are the trustees of the little Haahi and the Wahi Tapu.

Marama Stead nee Manukau has in her possession the historical papers of her Naani Pipi daughter of Hohaia Te Ru.Rawinia daughter of Pipi was one of the 12 owners. Marama is writing the history of her tupuna.

The little Haahi signifies a past where all the surrounding Maraes on the Kaipara are aitanga to the past officiating Church Ministers of the little Haahi, that are the descendants of Nga Waka Taua O Te Rarawa. I Charlene Walker-Grace of Kohai Matakohe have the last Book of the little Haahi that shows who attended the services dating back to 1889. The Little Haahi belongs to the 12 owners and all their descendants and all of Nga Waka Taua o Te Rarawa.The little Haahi is open to all who seek spiritual comfort. Charlene Walker-Grace

Te Whetu Marama Marae Kohai' Matakohe Kaipara.

descent.

Post a Comment

<< Home