When the bookworm and the prophet met

By the standards of this out-of-shape, couch-loving, getting-to-be-middle-aged bloke, 2009 has been a year of adventures.

I've sweated through the jungles of Samoa looking for prehistoric monuments and evidence of the depravity of Kiwi colonialism, followed the Indiana Jones-like Edward Ashby as he brought his archaeological skills to bear on the caves, buried walls, and ancient portage routes of Northland's Mahinepua peninsula, and stumbled through a sandstorm on the shores of the ancient and very dry Lake Mungo, deep in the Australian Outback. (I think that, if Skyler is not reading this post, I can probably risk calling the civil union we celebrated in January an adventure, as well...)

And yet, as TS Eliot and my old English teacher Ms Cournane were both fond of saying, there are adventures in art, as well as adventures in life. For me, one of the greatest adventures of 2009 took place not on the salt flats of the Outback or in the ravines of Samoa, but in the Special Collections Room of the University of Auckland library, where I slogged across the vast, sometimes arid, often strangely-detailed expanse of Kendrick Smithyman's papers between August and November. I'll be publishing two Smithyman-related books next year - one of them will be a collection of my ‘anti-travel’ writing inspired by his place-poems, the other will be a sampling of his uncollected writings with commentaries by me - and my excavations in Special Collections were aimed towards these ends, but they soon developed a logic of their own, as one freshly-unearthed document led to another. Maps can only take one so far.

I thought I'd show one of my excavated finds here, because it relates interestingly to a debate we had on this blog last Christmas, and to the discussion that my rather inadequate response to the St Matthews-in-the-city billboard has prompted over the past couple of days.

This time last year I googled Kendrick Smithyman's immense online Collected Poems, and discovered that rare thing - a very fine poem with the word 'Christmas' in its title. 'A Riddle at Christmas' bred an interesting discussion, as readers responded to the poem's description of a journey down the Whanganui River, past the utopian religious settlement that the great Kiwi poet James K Baxter established in the hamlet of Jerusalem, to the wild west coast of Te Ika a Maui.

One of the themes of the discussion 'A Riddle at Christmas' prompted was the difficulty of reconciling Smithyman and Baxter, as poets and as people. Baxter was a charismatic man, outspoken on social and political as well as religious issues, who wrote limpid lyric poems; Smithyman was a very private individual who was much more comfortable in a library than on a stage, and who wrote poems that sometimes seem to demand to be studied and decoded, rather than read and enjoyed. One of the contributors to last year's discussion insisted that Smithyman and Baxter represent a choice that every enthusiast for Kiwi literature has to make:

Smithyman and Baxter were poetic 'opposites'. Smithyman thought Baxter over-rated. There is an ironic tone to the references to Baxter in this poem. Sooner or later, all readers of NZ verse must choose between the two men.

And yet there are similarities as well as differences between Baxter and Smithyman. Both men were born in the 1920s, and were thus half a generation, at least, younger than the group of writers, painters, and critics who established what we can fairly call the school of modernist nationalism in New Zealand in the thirties and the forties.

In the thirties and forties, nationalist painters like Colin McCahon and poets like Charles Brasch and Allen Curnow surveyed the thinly-populated, philistine society they had been born into, and decided that it needed to be endowed with the sort of myths and symbols that only art in its most heroic guise can provide. Brasch wrote that New Zealand's 'empty' hills and plains 'cry for meaning', and McCahon responded by kidnapping angels and virgins from Renaissance frescoes and dumping them in the backcountry of the South Island. In a series of solemn and sonorous poems, Curnow turned the story of European contact with and settlement of New Zealand, from the foray of Abel Tasman to the uneasy settlements established by that pioneering venture capitalist Wakefield in the nineteenth century, into an epic without a hero, but with plenty of blood-smeared symbols.

As I noted a couple of weeks ago, in my rebuke to Chris Trotter's reading of my old mate Ronald Hugh Morrieson, the myths of the nationalists did not go unchallenged by younger writers and artists. Smithyman and Baxter were both unhappy with the way that the myth of an empty land seemed to simplify New Zealand history by ignoring the stories of Maori and of unfashionable Pakeha minorities. Both men also despised the puritanical, philistine, obsessively racist and super-patriotic society that was postwar New Zealand. As military adventures in Malaya and Korea and whites-only rugby tours of South Africa were justified in terms of Kiwi nationalism, the concept lost the magic it had held for some intellectuals in the thirties and forties.

Smithyman was a writer before all else - as Peter Simpson has memorably said, 'he spent his whole life in front of a typewriter' - so it is not surprising that his objections to the myths of New Zealand nationalism were made on the page, rather than on any public stage. For Baxter, the choice between the life and the work was more difficult, and led him to turn his hand to social campaigning and community-building as well as to sonnets and sestinas. In their different ways both men were significant critics of postwar New Zealand society.

Unlike most of today's social commentators, Baxter and Smithyman were preoccupied with the crisis of religion in the modern age. Like McCahon, who wrestled for years with Catholicism, and Curnow, who completed a theology degree and was en route for his first vicarage when he lost his faith during a particularly stormy crossing of the Cook Strait, Baxter wanted very much to believe in God, but struggled to reconcile this desire with an awareness of the reactionary role of many Christian organisations and the steady march of science into the realm of religious mystery.

Baxter's famous conversion to an inscrutable form of Catholicism in the '60s, and the strangely holy community of junkies and drifters he assembled deep in the Whanganui valley, represented an attempt to leap forward from the traditional Anglicanism and Catholicism that McCahon and Curnow had struggled with. Baxter wanted his community, and his own personal lifestyle, to be models for a new, improved Zealand, a place where material possessions were less important than aroha, and where anybody could kip down on anybody else's floor for the night. Baxter's experiment at Jerusalem and his continuing flow of self-dramatising poems won his ideas a large audience, but he failed to win many Kiwis over to his worldview. He died alone of a heart attack, on the doorstep of a stranger who had refused his agonised requests for help.

The most radical part of Baxter's thought was his notion that Pakeha and Maori were afflicted by the same spiritual crisis, and needed to come together to escape this crisis. With their rhetoric of an empty land without history, the nationalists of the thirties and forties tended to disregard Maori, and focus on the problems of a settler people in a strange new country. Maori belonged to the past; Pakeha were the future. For Baxter, though, the same forces which menace Maori - materialism, alienation from tradition, the break-up of family - also afflict Pakeha. It is hardly surprising that Baxter chose to give his mainly-Pakeha 'tribe' of followers the Maori name Ngati Hau.

Despite his iconoclasm, Baxter was in some respects a quite conservative thinker. By setting himself the task of becoming a 'healthy cell in the sick body of society', he affirmed a view of identity and history which has its origins and exemplars in the ‘advanced’ capitalist nations of the West. According to the view Baxter implicitly upheld, society is made up of autonomous individuals who make more or less informed decisions about how to interact with the world, and historical change happens when enough of those individuals begin to act in new ways. Neither Descartes nor Adam Smith would find anything objectionable in such propositions.

To read Baxter's relentlessly autobiographical poetry today is to admire the rage he felt towards the uglier parts of the world he lived in, as well as the grace with which he went about challenging the ugliness he found so easily. Whether he is puffing and sucking in dust at the Chelsea Sugar Works and decrying the lot of the industrial worker, rolling a cigarette for a junkie in a Grafton squat and lamenting the brutality of New Zealand's justice system, or chopping firewood beside the Whanganui River and admiring the naked bodies of his female followers, Baxter remains a tremendously engaging figure. And yet all of the poet's diverse activities, and all of the ingenious political tactics he deployed, were premised on the idea that the sick body of his society could be regenerated, a cell or a few cells at a time, through the power of exemplary individual action.

For Kendrick Smithyman, the conventionally individualist understanding of identity and history Baxter acceded to made no sense. By the time he reached his late twenties, Smithyman had arrived at an extremely unusual and extremely radical view of human identity, society and history. Like Baxter, and McCahon and Curnow for that matter, Smithyman lamented the decline of religion in the modern age. Like Baxter, if not McCahon and Curnow, Smithyman believed that the narrow, repressive society of postwar New Zealand was a product, in part, of the loss of the healthy traditions that religion had protected in pre-modern society.

Unlike Baxter, though, Smithyman did not believe that individual humans make history, and had no faith in the ability of campaigning intellectuals to turn the tide of history in one direction or another. In an interview with Metro magazine near the end of his life, Smithyman argued that 'we live inside history and language'. This somewhat cryptic statement reflected his belief that individual human identity comes from outside the individual human, and is involuntarily and unconsciously acquired, rather than freely chosen. We are who we are, Smithyman believes, because of forces we can seldom understand, let alone control.

Smithyman's views fused some of the doctrines of Marxism, an ideology he conducted a youthful 'love affair' with in the forties, with the later philosophy of Martin Heidegger. From Marx Smithyman took the notion that history is determined by economic, environmental, and technological forces, but not the notion that humans can act together politically to become masters of that history.

From Heidegger Smithyman took a deep suspicion of technology and scientism, and the idea that the modern era is characterised by an extreme 'technological nihilism'. Smithyman also found in Heidegger the notion that the human individual is something of an illusion, because human identity is only intelligible in terms of the network of relationships that humans have with both animate and inanimate objects. The individual human can be, at best, a sort of 'clearing', where other things manifest themselves.

For Smithyman, ours is fundamentally an irreligious age, and no amount of evangelising, whether from radical Catholics like Baxter or cultural conservatives like (say) Bob McCrokie, will affect that fact. Even if every single New Zealander joined a church, this society would remain irreligious, and God would remain dead, because those churches, with their emphases on individual self-improvement, their cause and affect understanding of morality and God's actions, and their tendency to produce vulgar and thoroughly worldy images of states of bliss and the afterlife, are simply reproductions of the industrial, materialistic, scientistic spirit of our society. A breach has opened up between the supernatural and the everyday, the ordinary life and the afterlife, the magical and the useful, and this breach cannot be healed. It is pointless, then, to try to reanimate God. Baxter was on the wrong road, even if for the right reasons.

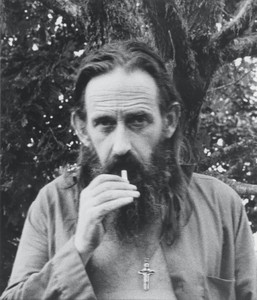

During the last years of his life the heavily-bearded, barefooted prophet of Jerusalem would make occasional forays into the University of Auckland, often with a troupe of followers, and sometimes to perform his poetry. On one of these visits Baxter encountered Kendrick Smithyman.

In March 1971, eighteen months before Baxter's lonely death, Smithyman sat down at his typewriter and tried to write a poem about his meeting with the man who had taken to calling himself Hemi. Smithyman produced four drafts of his poem, each of them quite different from the others. This draft, which was produced on the 28th of March, is the most polished, and was apparently intended for publication in Smithyman's 1974 collection The Seal in the Dolphin Pool. For reasons that are unclear, though, the poem was not published in that book, nor in any subsequent Smithyman collection.

I'll offer my own commentary on this extraordinary text in a later post, and in doing so try to substantiate some of the alarmingly bold statements I've made about Smithyman and Baxter in this post. In the meantime, tell me what the poem means to you!

LETTER ABOUT HEMI

From this bach I set out

lines like antennae, towards that man

lion-maned, in the lion's skin

of wilful poverty. He lugs his burden,

a public conscience. Romantics call it soul,

of a poet. Him I met

on a stairway of the Library/Arts

Building. His life-style packed his arms.

Mine, cumbered with books, notes

for classes, and apology.

We embraced.

It is hard to embrace.

An undemonstrative people, we care

to play it cold. Fate or the Dog,

is it fate or the Dog that harks

our footfall, or merely aptness

for the Absurd? He offered aroha,

and I stepped on his bare toes.

His son, whose mother is Maori, stood

at the mezzanine landing

looking down to the dispossessed

fathers, elders of a landless tribe.

Those who think it affectation

that he should change his life and worse,

his name, criticise him. Traditionalist,

as though baptismal he took

a Maori name. Why not?

I respect his gesture.

His way forward may be the way back.

In any case, I read in a letter

from East Africa words quoted

of a student: 'We are all

cultural mulattos...' Some by

genetic accident, some by social

circumstancing. By act of will,

Hemi, not many. That feeds on

Ercles' vein, a tyrant vein.

10 Comments:

i've found some of the other smithyman poems you've posted almost impenetrable, but really love this one. i guess the detailed background helps the reading, but there is a directness of expression that i really relate to. of particular resonance is 1) the image of having arms full of lifestyle 2) the bit about us all being cultural mulattos, and how/why.

intend to pick up a book of smithyman's work, any suggestions on where to start?

Hi Feddabonn,

the neat thing is that Smithyman's Collected Poems are online, so you can read 'em for free:

http://www.smithymanonline.auckland.ac.nz/

Mind you, reading on the screen will never, so far as I'm concerned, compete with nestling in bed with a tatty old paperback!

If you dislike old Smithy's convolutions (and I do understand where you're coming from), but find his worldview interesting, you might enjoy his posthumously-published book of poems about his family history, Imperial Vistas Family Fictions:

http://www.smithymanonline.auckland.ac.nz/document.php?action=null&wid=1093

His books are in many second hand shops. But his poems can be found in old anthologies of NZ Poetry...so the "Penguin Book of NZ Verse" edited by Curnow has poems in by him. And I am sure most other NZ Poetry anthologies.

I don't - or rarely - read through much on the screen - I prefer having a book to read.

But he was never a Marxist Maps!

I remember him musing aloud about R A K Mason and how his (going into) politics meant the stopped writing (or to that effect).

Also I recall him saying in an interview that he found Marxism nonsense.

Mason, however, was a Communist as was Tuwhare. Mason was, however, like Baxter and even Tuwhare, also influenced by the idea of Christ and Christ being a figure of justice, or the symbol of suffering Man.

Many of Baxter's poems - his earlier ones show Baxter's considerable erudition - in fact in formal terms he was the more highly educated - as was Mason.

Of course Smithyman was nevertheless a polymath... I liked Smithyman and his rambling on about Heidegger and so on - even about Dylan Thomas, Eliot etc, and his Buller's Book of Birds or which he was greatly proud...

I recall he was very interested in my essay on some writing about NZ by D'Arcey Cresswell (which I and he found very subtle, satire I think, but I was very young and I cant really recall what it was that interested me!).

I initially found his poetry difficult. (I still do - some of it is impossibly so - but some of Curnow's poetry is also, for example - in fact much poetry I find very difficult and often almost incomprehensible - including my own!!) But the early poetry of Baxter is as complex (or "deep") in many ways.

Smithyman was a Modernist and those of Eliot's generation and later liked to make things difficult.

I would be a bit hard pressed - as with most of Smithyman's poems - to give an explanatory summary of what this poem is "about" but he seems always to be actually NOT reaching conclusions as such, and there is sense that he is constantly thinking. Constantly seeing "angles", constantly reevaluating, rethinking. Like Bloom in 'Ulysses' by Joyce, we hear his thinking.

He sees that the difference between them is real but not as much as perhaps might be thought of one who has moved from academia (but in a way is still there) to another who is also always "in" academia, "cumbered with books"...

Smithyman wonders if it is fate or the Dog (God backwards hence the devil? Or perhaps Diogenes "surname"? Other? ...) or The Absurd (Existentialism, The Theatre of the Absurd, Beckett etc) that "dogs" or harks their footfall, and then he steps on Baxter's toes so - that rules out any Romantic fate guiding their meeting!

(Cleverly again the phrase: "Hark hark, the dogs do bark! The beggars are coming to Town." is re-echoed here. The choice of the word "hark" and the reference is not accidental.)

I have a sense that Smithyman never quite settles for one idea though - he respects Baxter (his gesture, to become Maori (or change his life and "worse" his name)) and his almost Romantic (and, remembering that Bryon died fighting for real freedom), even Bryonic role, his "lion's mane" and his passion, even his (White Man's?) "burden", his "public conscience"... But the final "address" somewhat reevaluates, or "re-sees" that side or aspect of Baxter...

"....

some by social

circumstancing. By act of will,

Hemi, not many. That feeds on

Ercles' vein, a tyrant vein."

Here 'Ercles vein' according to the online Encyclopedia Britannica, refers to bombastic or overblown speaking or writing, or excessive rhetoric and comes from a phrase in Midsummer's Nights Dream (about Hercules..."Ercles")...

On the one hand it is admirable (implied) that not many have changed in the way Baxter did "by act of will" and in the next line it can (the language and the "presentation" of Saint Baxter etc) lead perhaps to tyranny

(at least so kind of tyranny of language or ideas). But Smithyman also is constantly seeing himself and Baxter, and as well as that both are of the "dispossesed" Pakeha "elders of a landless tribe" (who cleverly, as is Smithyman's way,) are "looked down upon" by (at least one) Maori...they have points of contact - and Baxter's later works are close to those of Smithyman's (the details, the "realism" and the introspection, the ideas...less perhaps the language but Baxter was very influenced by Maori expressions and ideas).

But Smithyman is for complexity of ideas and language, and less for perhaps the kind of reduction Baxter wanted. Without being cynical he cant adopt any role as a "prophet". But his style is not in itself complex or difficult. It is, like Browning's, or others of that kind, poetry that talks across time to the reader and says: these were my thoughts.

Richard,

have you read the Smithyman-Parsons letters?

http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/kmko/05/ka_mate05_letters.asp

The young Smithyman affirms his belief in Marxism explicitly there.

Maps - I haven't - I didn't know those were there. They are fascinating letters. I couldn't find the thing about Marxism.

However it is amazing the letters are there. I read one where his mother died...

In the letters it seems one can see his style evolving.

Did I solve the Smithyman Poetry Puzzle?!!

I must have a good look at those letters. It has the detail, and the wonderful rambling coefficient, of the Olson-Creeley letters which I have argued almost constitute a kind of proto-post modern poem themselves (in toto) if anyone has the time to read through them!

Hard case that he gets to the Islands (after parts of NZ) and his letters are as if he was traveling through Outer Mongolia almost!! Eerie entry the ref to Max

of 'Angry Penguins'...I suppose Ern Malley comes up...

This letter's beginning rang a bell -

AC 2

Levin

Sunday morning 8 [August 1943][59]

Dear Gray,

Sunday morning “fate’s great bazaar” and me sitting in the sun outside the hut. This place gets on my nerves, particularly when I want to write and can’t which is the way I am at present. ...

Levin ......."

'Fate's great bazaar' is from Louis MacNiece's poem "Sunday Morning". He clearly had read it, as it was written in 1933. So add a few years and Smithyman is 15 or 17 or so.

The letters are fascinating - beautiful writing at times. Smithyman commments at one stage that Communism is at least a chance.

Here is the quote I saw:

"...The wise and journalists who like to ticket things will have to find another lable [sic] for us since they ticketed our elder brothers with The Lost Generation.[70] Christ knows they’re a generation of picnicers [sic] to us who were born after one war, schooled in the depression, and graduated into the Army.

We have seen virtually all things shattered. We are, those of us who think, sophists by birth and confirmed in the habit of doubt. What values can we take as permanent? Precious few out of our way of life. If we go back to the country and look at the soil for strength, we find it betrayed and betraying. At the best the humanist spirit of this country, of its roads, its paddocks, hills crops and waters, is a palliative and not a matter for life itself. I see little remedy or hope in anything, though I turn more and more to Communist philosophy as a chance. Chance we must reckon on, since so much has been born from it.

So we must trust—though that’s the wrong word—that the good fairy will remember us after the war, give us a certain measure for security, a drop or two of some anodyne to make things right that we may for a while at least, spit in the eyes of the seven sisters trying to blind them.

Please pardon this bastard of a pen. It’s hell to write with & my script’s lousy enough at any stage..."

Maps - I think your summary of Smithyman's world view here is pretty insightful. I was concerned you might be making him more of Marxist than he ever was - but I re-read what you said...

He was always subtle, and often an emotional and sensitive, thinker: and I think that follows in his poems - they are poems such that as one reads them one feels a flow of thoughts, connections, and questions...

I believe you are now in Tonga?

Interesting to see the next chapter of Maps! And what devilment or profound evil you find in the isles of the "south"! My next door neighbour is Tongan I will up date him when you are back....

Greetings to one and all: In that most precious name. That name which is above every name, the name: "Jesus"

There's tremendous power in that name. I'd suppose we'll never fully realize all that can truly be accomplished, by us simply calling out that name in true faith.

There's an old, old, gospel song that goes like this: Faith in the Father, faith in the Son, faith in the Holy Spirit, great victories are won. Demons will tremble and sinners will awake, faith in Jehovah will anything shake.

For you who have never come into this realization, if you're reading this, just give him a welcome into your heart and life. You will both feel and see an awesome difference. You will have also purchased the ticket to heaven (by accepting, therefore making him welcome to come into your life. You will also sup from His cup that contains living water. (As did the woman at the well of Bethesda.) John 4:10

Much love,

Your brother in Christ Jesus, who is both our Lord, and Savior.

com/BeyondTheGowww.eloquentbooks.ldenSunsetAndByTheCrystalSea.html

http://www.eloquentbooks.com/OffToVisitTheProphetElijah

Post a Comment

<< Home