Six quick notes on Tonga's stolen election

[I've only just heard the depressing news from Tonga, a place which seemed full of confidence just a few weeks ago. These quick notes are meant to stimulate a bit of debate, rather than to make some sort of definitive statement on what appears to be a very complicated and fluid situation...]

[I've only just heard the depressing news from Tonga, a place which seemed full of confidence just a few weeks ago. These quick notes are meant to stimulate a bit of debate, rather than to make some sort of definitive statement on what appears to be a very complicated and fluid situation...] 1. The election after the election

In the general election held in Tonga on the 25th of November 'Akilisi Pohiva's Democratic Party won twelve of the seventeen popularly elected seats. Excited journalists called Pohiva a 'Prime Minister in waiting'.

Now, nearly a month after Tonga's election, Pohiva and his party have been sidelined, and a man elected by a few dozen voters has been annointed as the new Prime Minister of Tonga. Lord Tu'ivakano is one of nine members of Tonga's parliament elected by the country's tiny class of nobles. In the weeks after the general election, Tu'ivakano has gathered the support of the other noble members of parliament, and of most or all of the five popularly-elected members who do not belong to Pohiva's party. When parliament met earlier this week to elect a Prime Minister, Tu'ivakano defeated Pohiva by fourteen votes to twelve.

2. Outmanoeuvred by nobles

Tu'ivakano's election as Prime Minister makes a mockery of the election held on November the 25th. That election was supposed to set the seal on a process of reform which began late in 2006, shortly after the coronation of King Tupou V. The aged father of the new King had for decades resisted demands that Tonga's monarchy relinquish its near-absolute power and allow a government of elected commoners to rule in its place. Tupou IV's obstinacy had frustrated many Tongans, and in November 2006 a pro-democracy protest march in the country's capital Nuku'alofa turned into a riot which destroyed seventy percent of the city's business district and killed six people. Martial law was declared, and Australian and New Zealand security forces were flown in to patrol the ruins of the central city.

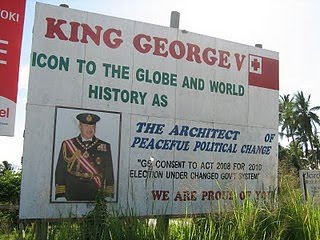

After the chaos which greeted his accession to power, Tupou V unexpectedly identified himself as a proponent of democratic reform. The new King initiated a byzantine process of reviews and debates which led to a number of changes to Tonga's consitution. These changes allowed for the majority of members of parliament to be popularly elected, and for the country's Prime Minister to be elected by parliament, not selected by the King.

After the chaos which greeted his accession to power, Tupou V unexpectedly identified himself as a proponent of democratic reform. The new King initiated a byzantine process of reviews and debates which led to a number of changes to Tonga's consitution. These changes allowed for the majority of members of parliament to be popularly elected, and for the country's Prime Minister to be elected by parliament, not selected by the King. The campaign which preceded the election on November the 25th was marked by excitement and optimism on the part of the pro-democracy majority of the Tongan population. Candidates campaigned noisily, cruising the streets in trucks and utes rigged up with PA systems, and holding mass meetings in churches and halls. Tongans turned out in huge numbers at polling stations on the 25th, and the revelation that 'Akilisi Pohiva's pro-democracy party had won a big majority of votes and a large number of seats prompted widespread celebrations that evening.

Pohiva himself seemed initially to believe that his party's high vote had brought him to power. In interviews with international media in late November he presented the creation of a government as a formality, and signalled his intention to take the post of Prime Minister.

But Tonga's nobles quickly began to reach out to independent popularly-elected members of parliament, offering them government ministries, as well as more informal bribes. A number of the independents came from Vava'u, Tonga's second largest island group, and the nobles were able to play on the rivalries that have long existed between Vava'u and Tongatapu, the country's most populous island and the base for Pohiva's party. The nobles also attempted to sway the members of parliament for the Democratic Party, and the secret nature of the ballot for Prime Minister may have allowed one or more members elected on Pohiva's ticket to betray their supporters and their leader.

Lord Tu'ivakano has called his election as Prime Minister a 'victory' for 'Tongan tradition', and a rebuke to the 'party politics' of Pohiva. The reality, though, is that Tonga's nobles have acted as an unofficial party, and have undermined the wishes of a large majority of Tongan voters. It is hardly surprising that local political commentators like Malaki Koalatangi have criticised the election of Tu'ivakano, and warned that frustrated Tongans might once again resort to rioting.

3. In the shadow of Tupou I

The struggle between nobles and democrats over recent weeks has its roots in Tonga's peculiar history and sociology. Before the arrival of Europeans, Tonga was a centralised, high organised society, where a feudal class ruled over a mass of small farmers. After a period of civil war in the early nineteenth century, King Tupou I reunited and reorganised the country. Thanks largely to his efforts, Tonga was the only Polynesian society to avoid coming under the control of a colonial power in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Tupou I tried to strike a balance between traditional Tongan ways of life and the demands of Christian and other newly-imported ideas. Worried by the fate of the Waikato Maori, who lost almost all their territory to invading European colonists, he made sure that the constitution he framed for Tonga banned the alienation of land. Inspired partly by Tsar Alexander II, he emancipated Tonga's serfs, and guaranteed them security of tenure on the small plots of land they farmed. Although Tupou's constitution decreed that all of Tonga was ultimately owned by the monarch, it also ensured that any Tongan man could request eight acres of land to work when he came of age, and that he had the right to pass access to this land on to his eldest son. The feudal lords who had enjoyed power of life and death over the small farmers were converted into state-subsidised nobles, and were charged with responsibility for the distribution of land to small farmers.

The system Tupou I created allowed Tongans to hold on to its economic and political sovereignty, and gave small farmers a better life without breaking the power of the old feudal class. Tupou I's system also for a long time prevented the growth of capitalism in Tonga, because it made both the investment of foreign capital and the accumulation of capital by Tongans very difficult.

In recent decades, though, capitalism has spread through Tonga, and the system Tupou I created has begun to break down. Encouraged by Western governments, King Tupou IV invested large amounts of capital on infrastructure like roads and ports, and called on Tongans to grow crops for export as well as for subsistence purposes. Since the 1960s, a series of 'miracle crops', from bananas to vanilla to squash, have fetched high prices abroad for short periods, and spread the cash economy into remote islands.

As the population has grown and the number of allotments available to new farmers has shrunk, nobles have been able to take increasingly large cash bribes in exchange for distributing land to the 'right' party. They have invested some of the income provided by these bribes in businesses. Nobles, and the royal family in particular, have also benefitted from the monopoly businesses that the Tongan state has protected and funded, like Royal Tongan Airlines and the country's satellite and telecommunications companies. Led by the royal family, Tonga's nobility has converted itself from a feudal into a capitalist class.

At the same time, a Tongan working class has emerged, as the sons and daughters of farmers have taken up jobs in state owned enterprises or in nobles' businesses. A protracted strike by public sector workers in 2005 signalled the arrival of a strong Tongan trade union movement.

The growth of capitalism in Tonga has placed pressure on Tupou I's system. Both export farmers and business owners expend huge amounts of energy struggling to get access to land using an inefficient distributive system administered by a blatantly corrupt nobility. The small size of the country's farms makes economies of scale impossible, and limits possible export markets, and the hold of the nobles on the business sector frustrates innovation. Large numbers of Tongans have gone abroad to work, and seventy percent of the country's Gross Domestic Product comes from the remittances these young men and women send home. The latter-day colonialists who staff bodies like the International Monetary Fund and the Asian Development Bank have used Tonga's problems as an excuse to urge an end to the ban on land sales and the removal other obstacles to foreign investment in the country.

4. When integrity is not enough

'Akilisi Pohiva's Democratic Party draws its support from the many Tongans who feel excluded from the mainstream of their country's economic and political life. Pohiva's party has longstanding links with the trade unions and with small export farmers, but it also includes many budding entrepeneurs from outside the noble class, like the high-profile travel agent and MP Semisi Sika. The party's ideology has often described as 'left-leaning', or even 'left-wing', but it might more usefully be compared to the anti-materialist, morally-charged politics of nineteenth century 'Old Liberals' like the Briton William Gladstone.

Pohiva believes that a 'culture of corruption' allegedly created by the nobles is responsible for virtually all of the ills of Tongan society, and that if the nobles can be prised from the controls of the state and the economy then all other Tongans will be able to unite, to purify their conduct, and to develop their society with unprecedented ease. Without corruption in the way, the economy would supposedly boom. In the interviews he gave with the media after his apparent victory last month, Pohiva talked almost obsessively about the need to complete the clean-out of nobles from Tonga's parliament and to open the books of government ministries notorious for corruption.

Pohiva believes that a 'culture of corruption' allegedly created by the nobles is responsible for virtually all of the ills of Tongan society, and that if the nobles can be prised from the controls of the state and the economy then all other Tongans will be able to unite, to purify their conduct, and to develop their society with unprecedented ease. Without corruption in the way, the economy would supposedly boom. In the interviews he gave with the media after his apparent victory last month, Pohiva talked almost obsessively about the need to complete the clean-out of nobles from Tonga's parliament and to open the books of government ministries notorious for corruption. In the last fortnight before the election of Tu'ivakano as Prime Minister, Pohiva took to calling for a 'Cabinet of national unity' which could enjoy the support of all twenty-six members of parliament. Pohiva would lead such a government, which would offer ministries to nobles who were prepared to put Tonga's 'national interest' first and avoid their old debased ways. Pohiva's call for a broad-based government was a tactical manoeuvre necessitated by his weakening position, but it was not inconsistent with his belief that Tonga's salvation lies in the elimination of corruption.

Pohiva is a man of great integrity, who has exposed numerous cases of government corruption over the last two decades and been jailed twice for his troubles. Pohiva's personal popularity had a great deal to do with the huge number of votes his party won last month. But Pohiva and the other leaders of the Democratic Party have consistently failed to recognise the structural nature of the problems Tonga faces, and the absurdity of the notion that the Tongan nobility will voluntarily surrender its hold on political power.

As an isolated, underdeveloped society with few natural resources and a constitution which makes foreign investment and capital accumulation difficult, Tonga lacks the preconditions for the sort of capitalist economic boom Pohiva desires. Lacking a large domestic market or many steady export markets, the country's capitalists can only make good money when the state acts to give them a domestic monopoly on some product or service, or when it awards them access to land and other resources at bargain basement rates. The corruption and parasitism of the nobles is not an aberration caused by moral decay, but an expression of the limitations of capitalism in Tonga.

The nobles cannot revert to being a feudal class, as they were as recently as fifty years ago. They can only survive as capitalists, and given the nature of Tongan society they can only pursue capitalism if they control the state. They cannot, then, contemplate relinquishing power to Pohiva's party. (Nor, for that matter, can the nobles proceed too far with the sort of liberalisation of the Tongan economy being demanded by the likes of the IMF. The IMF, after all, wants to take the state out of the Tongan economy, in accordance with neo-liberal doctrine.)

5. The strange role of Tupou V

5. The strange role of Tupou V The reforms which led to the election of November the 25th occurred not because of the righteousness of the arguments Pohiva has been making for decades, or the ferocity of the rioting of 2006, but because of the personality of King Tupou V. The monarch is an eccentric, unworldly man who is far happier in the restaurants and museums of Europe than he is anywhere in the South Pacific. He has described himself as a 'captive' of Tonga's political system, and has expressed his desire to 'free' himself by giving up most of his powers.

Tupou V's support for reform has upset many more worldly nobles, who recognise that their future depends upon keeping commoners away from the levers of political power. During the lead-up to last month's election, Tupou V acted to foil a number of anti-democratic manoeuvres by the nobles. He refused, for instance, to allow his designated successor, Crown Prince Topouto'a Lavaka, to put his name forward for election to one of the parliamentary seats reserved for nobles. Tupou V understood that the Crown Prince would have won a seat, and that there would have been tremendous pressure on commoner as well as noble members of parliament to elect him as Prime Minister. After he had stymied the Crown Prince's candidacy, Tupou V called on Tonga's elite to accept that, under a democratic system, the country's Prime Minister ought to be a commoner, rather than a noble. But Tupou V's surprising support for democracy was ultimately no match for the brutal realism of the rest of his class.

6. What's next?

6. What's next? If Tongans respond to Lord Tu'ivakano's illegitimate government with a new uprising, then the leaders of the pro-democracy camp will have some fateful decisions to make. 'Akilisi Pohiva was imprisoned after the rioting of November 2006, but he has always denounced violence in the pursuit of political ends. Will he abandon what may seem like an increasingly utopian stance? Under Tonga's constitution, Tupou V has personal control over Tonga's five hundred man army. Will he deploy them to protect Lord Tu'ivakano's regime, or to try somehow to rescue the reform process he set in motion late in 2006?

19 Comments:

Great post Maps, all the information I get from Tonga I get from you. It just doesn't find its way into NZ's media somehow...

'A Radio New Zealand correspondent reported that most of the speakers in Parliament's session on Monday supported Pohiva, who himself spoke of his long experience in Tongan politics and how he could help the country toward full democracy.

Lord Tu'ivakano said the executive and Parliament needed to work together in the new era of Tongan politics.

The correspondent said soldiers backed a strong police presence at Parliament for the first time since pro-democracy demonstrations in 2006 erupted into violence, in riots that killed eight people and destroyed three-quarters of the capital.'

Wikileaks on Tonga

http://www.michaelfield.org/wikitonga.htm

a lot has changed

Posted at 16:49 on 25 November, 2010 UTC

Tonga’s nobles say they want the country’s new prime minister to come from the people’s representatives.

Results in the country’s historic election are due this evening but the nine nobles chosen by the nobility have been revealed.

They are the Honourables Tu’i Afitu, Fusitu’a, Fakafonua, Ma’afu, Tu’i Vakano, Tu’i Ha’ateiho, Lasike, Vaea and Tu’i Lakepa.

Our correspondent in Nuku’alofa says the nobles revealed it is the King’s wish that a commoner become the next prime minister and they have to make that happen.

“They all think that unless the elected representatives all work well together there is not a lot of hope for Tonga and so the messaging from them is about this co-operation and a consensus approach to the political system.”

News Content © Radio New Zealand International

PO Box 123, Wellington, New Zealand

Fwd:

This outcome remains undemocratic since 9 representatives of the 33 nobles (including this new PM) in Parliament were not elected by the people, but by the Kingdom's 33 nobles. Democracy is about the rule of the people and to be democratically legitimate the new PM should have come from those representatives (17 reps) elected by the people only. The outcome of this political reform has amounted to nothing. This outcome reveals that we are still in the old despotic regime. The NZ-based "New Zealand Tongan Development Society Incorporated" is calling on all the pro-democracy supporters in Tonga and New Zealand to return back to the battle field and continue the fight for democracy for the Friendly Islands. The king and his 33 nobles must read the writing on the wall: full democracy for Tonga or no more kingdom. The people should elect all the representatives in Parliament, which means the 9 seats reserved for the nobles must be abolished.

Finally, may I advise this forum that this Tongan Advisory Council is an unregistered 'one-member' setup. It's not a group as it's made up of one person only. Check the registered Incorporated societies in NZ and you'll find none under that name.

Sosefo Holani

The NZTDS Secretary.

So...there are no solutions?

Get over it...its time we move on: your article is misleading and full of... and its not worth much of a discussion on this forum.And another thing,please, check your sources before you can talk.Of course we all support a democratic reform,but to say that Mr.Pohiva was robbed? Please,'oku 'ikai koha me'a ia 'ene tamai ke 'iai ha'ane totonu kiai. Get it. Don't waste your saliva on this kind of madness. Instead,say something that will make our people move forward. Please keep your problem to yourself.

Faka'apa'apa atu

Concern Citizen

Hint to last commenter: it's always helpful to cite some examples when you talk about false claims and 'madness'. I can't quite see how the notion that a party which wins seventy percent of the vote in a general election deserves to form a government can be considered 'madness'.

The last commenter should really dwell on the message behind the extraordinarily high vote for the Democratic Party of the Friendly Islands. There are very few examples of a democratic national election anywhere in the world in which one party has won anything like seventy percent of the vote.

In New Zealand, no party has ever won anything approaching fifty percent of the vote at a national election.

The few parallels to the Democratic Party's vote concern broad-based democratic movements contesting the first free and fair polls in their country's history. The African National Congress won over eighty percent of the vote in South Africa's first post-apartheid election; Fretelin got a huge majority in East Timor's first post-independence election.

In South Africa and East Timor, voters wanted to show their overwhelming support, not just for a particular party, but for the whole concept of democracy. I think that the same desire is behind the huge vote 'Akilisi Pohiva's party got on November the 25th. The nobles have chosen not just to sideline Pohiva but to snub their nose at the very concept of democracy. I can't see that going down well.

Very true...I admire your post and what you revealed is the truth behind the election.There is a Tongan saying which reads and I quotes,"'Oku mate pe Tongaa he ngaue 'ae Tongaa"In English it translates as "Tongans do backstab his fellow Tongans" It explains the fact that the other common MP or the independent MPs(IMP)as they called themselves,sold their soul and betray their poor brothers who were voted on by 1000s of poor Tongans to support the rich nobles voted in by the other 33 nobles.George Tupou V,a very understanding King had voiced his demands and yet,the nobles like your blog can not resist their hunger and greed for power fuelled by these IMPs lusts for honour.May they all rest in hell...Chin up 'Akilisi for you and your party had won OUR HEARTS AND SUPPPORT ONCE AGAIN.

Anon wrote:

'So...there are no solutions?'

I'm not an expert on Tonga and am certainly not in any position to offer detailed advice to Tongans on how to run their pro-democracy movement. I'm more interested in in analysing the larger forces which are making the advance of democracy in Tonga so difficult, and in getting a little bit of information out to my fellow palangi down here in New Zealand.

Having said that, there are some basic questions on which I think it's fair to take a position from this distance. One concerns whether or not the democrats should cooperate with the new government.

It's likely that the new illegitimate government will try to draw in members of Pohiva's party by offering them ministries.

Reformers are always in danger of being co-opted by the establishment which they oppose.

The co-option of Zimbabwe's opposition by Mugabe, via a 'government of national unity', is a case in point.

With Tonga facing an economic crisis caused by a sudden decline in remittances and the IMF and other bodies piling on the pressure for neo-liberal 'reform', the Tu'ivakano regime may well embark on cuts in social spending and cuts to the public service workforce in 2011. That will add insult to the injury of the stolen election.

Pohiva would be better off to refuse to accept the legitimacy of the government and to campaign for new, properly democratic elections.

Here's a joke:

WASHINGTON — US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton praised democratic progress in Tonga on Wednesday after the prime minister was elected by parliament for the first time rather than being a royal appointee.

Siale'ataonga Tu'ivakano was sworn in as prime minister on Wednesday after edging out pro-democracy activist Samuela 'Akilisi Pohiva in a November 28 ballot by the first popularly elected parliament in the Pacific archipelago.

"I congratulate the people of Tonga on taking another step toward democracy with the election of Noble Lord Tu'ivakano as Prime Minister," Clinton said in a statement.

As a supporter of democracy and a supporter of AP. The process was fair in Tonga when there's a 'hung parliament' or else AP would've argued the point before the voting process. The fact is he didn't so it sounds like 'the movement' is crying over spilled milk. This post does scream of sour grapes and we should really accept the decision for what it is. AP lost and the noble won. In as much as people dont like decisions from elections all the time. Liberals win, conservatives lose. Conservatives win, Liberals lose. We need to take it on the chin and work forward.

Dr Halapua has on paper better credentials and is proving himself a worthy leader of 'the movement'. AP has been a great leader and I think it's time he rethinks his position and let someone else take it forward.

Fresh thinking and perspective is needed for real change and not throwing mud. Throw solutions on the table instead.

As for Michael Field, his ethnocentric holds very little validity in my view. His lens is tarnished and his writing seems very myopic. Rarely solutions focussed. He's one of these people that goes into Pacific countries thinking he has all the answers from his epistemic world view which is neither indigenous to the countries. He knows very little. He should let the people find their solutions.

He thinks he knows Fiji says the rebels are this and that. Well, all he did was push them closer to China. Rarely constructive. Sometimes journos need to be more objective in their writings and be more pragmatic and less pious.

Lord Tu'ivakano may not be the best person we think is best for the job but the process has chosen him and we have to live with it.

Cleaning up the spilled milk.

'AP lost and the noble won'

'AP' certainly did win, according to any reasonable standard. He led a party that got 70% of the vote; by contrast, the man who has become Prime Minister got a couple of dozen votes. In any democratic country without the nine seats guaranteed to nobles Pohiva would have easily formed a government.

I hope I didn't say I agreed with everything Michael Field says. I thought the book he wrote on the Mau movement a couple of decades ago was very good, but I was surprised by how splenetic and unscholarly the discussion of Tonga in his recent book Swimming with Sharks was. There was the odd telling detail there, though: the anecdote about the noble who gets his retainers to wash his hands, for instance, says a good deal.

I have a solution:why not let the people choose both PM and MPS. If not, then its better to register two to three parties:e.g, Temo,independent,and Republican.Each side will provide a candidate for the office of PM,if he went on to win, let his party chooses all ministers and run the gocernment.

Its too late now, but if the people were given that opportunity, AP would have won by a big margin, end of the problem.

Faka'apa'apa atu

Concern citizen

Hi Scott. Sorry for the spam but it's super hard to find you email! Thought you might be interested in some research of mine:

http://garagecollective.blogspot.com/2010/12/little-packet-containing-ashes-of-joe.html

I'd be happy to send you my draft if you wanted to cast a critical eye over it...

Jared

can i jump on the wagon? AP accepted the PM's offer into his govt...strategic? I would like to think...as he (AP) has clearly stated...now our concerns are less to do with votes and "democracy" than with whether AP's cause would be compromised along the way as a gov.minister. or not...most public opinions prior to AP's acceptance of the PM's offer called for him not to accept it...I would say 90% of those opinions...yet AP took the offer claiming that his democratic cause will never be compromised as he is not required to be sworn in(to) Parliament...Ministers are not under the same obligation as the PM and are not sworn...I suppose in this sense, all we can do is wait and see how this thing play out...may be it's for the best as now AP is under the people's scrutiny whether he is what he says he is and whether he has the ability to lead the next govt...test of character aye bro

i am a commoner who lives in Tonga but i am currently on vacation overseas... and i can definitely say that a lot of what you articles says is misleading and in some instances blatantly false. Akilisi to me is just words with really no substance... believe me when I say your blog isn't saving or helping anyone...

Thank you for this. Please, sir, could you correct the major error in the piece? It is very important. 'Akilisi may have personally gotten over 70% of the votes in his district, but his party as a whole (including the votes for 'Akilisi) got around 30% of the popular vote. In 2010, over 70% of the population did NOT vote for the party. Thank you.

Yes, anon, that was a misapprehension I had. I knew the FIDP took about 70% of the seats in parliament, but wasn't aware it only got 30% of the vote.

I tried to correct the error in a later piece about Tongan democracy:

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.co.nz/2014/06/why-tongan-democracy-should-interest-us.html

Post a Comment

<< Home