[

[Last month I

posted an interview with Vaughan Rapatahana, the poet, educationalist, and language activist who lives in Hong Kong but considers the small town of Te Araroa near the East Cape of Te Ika a Maui to be his home.

After I interviewed him Vaughan sent me a couple of articles in which he reflects on his visits to the Micronesian nation of Nauru. The first article was first published in the

Post Primary Teachers Association Journal in 1983; Vaughan has added some asides on recent Nauruan history to it. Vaughan's second article, which I'll post next week, records a return visit to the island in 2010.

Vaughan has been busy lately putting together

The English Language as Hydra, a book of essays by a range of scholars about the threats which Anglicisation and globalisation pose to the languages and cultures of the Pacific.

]Yes, I went to Nauru: 1979 - 1981by Vaughan RapatahanaYes, I went to Nauru. I went there in April, 1979 to “teach English”. I have never been the same since.

I was a young, relatively naïve and inexperienced teacher at a school in the north of New Zealand, who after two and a bit years felt restless, bored, impatient, a little dissatisfied with the sheer racial bias against/ignorance of things Maori. Yet, I had two young children, a fine new schoolhouse with a cheap rental and I enjoyed my job and the company of the teachers I worked with. At least most of them.

So why Nauru?

One afternoon, in the ‘Situations Vacant’ column of the

NZ Herald, I noticed an advertisement calling for teachers for Nauru Secondary School, Central Pacific. I applied, probably more in a fit of ennui than anything else, and thought nothing more of it. Later that year I was contacted by Nauru’s Senior Administrative Officer (the ex-Town Clerk of Ashburton, New Zealand). Would my wife and I come down to Auckland for an interview? Sure. So off we went. We asked a few questions, he mumbled a few replies and gave us a large wad of money as expenses.

Soon after, I was told that I had the job. After a bit of frantic fact-finding – for few people had even heard of the place – we decided to go. Why not? I gave and served the requisite two months notice, and as a bonus received two year’s leave of absence from a generous school board. We were off.

On reflection, I can only say that my motives were greed – good, tax free money on Nauru – and adventure. I guess I’d read too many

Biggles books or something. Certainly there was no element of ‘helping the natives’, given that I had a particularly indigenous insight into things anyway. On reflection, I was symptomatic perhaps of expatriates everywhere, although I would like to think that I was more culturally sensitive and aware than most.

We climbed onto an Air NZ jet and were whisked away to Fiji for a two-day stopover before an Air Nauru flight to the island. Back then, Air Nauru operated more than the sometimes mechanically bedeviled aeroplanes it now has, although back then also, Hammer deRoubert, the island’s leader, was prone to commandeering planes for shopping trips to Hong Kong, whilst their transient passengers were left temporarily stranded as longer-term tourists on Nauru!

My first impression of the 12 square mile (21 square kilometer) island was one of heat: it was bloody hot. A welcome of sorts from a newly appointed Headmaster, from Wellington, N.Z, and we were shunted off to an upstairs flat where a few supplies had been laid on and where the fans only seemed to stir up the heat. This was to be our home for “a couple of months” while our house – in an exclusively expatriate government workers’ settlement on the other side of the island – was readied i.e. painted. We had no car and there was no public transport. There was only one supermarket, which specialized in not having much of anything except weevils, corned beef and a roof that leaked directly onto the counter whenever the infrequent, but heavy, rains came. This supermarket, by the way, had fresh vegetables delivered only once a week – on a Saturday morning – and it was then that a selfish melee used to break out among the expatriates and the local Chinese to be the first to score a cabbage.

There was a Staff Club, the bastion of many of the white male population of Nauru, who drank the pink gins served up by one Lee Kit, the fulsomely ever-smiling barman, who knew only enough English to serve the drinks and to mouth obscenities at those patrons who seriously tested his patience during rush hours. Alcohol was extremely cheap: a can of Fosters beer was only 22 cents back then, whilst Fanta was 30 cents. Nauruans scarcely ever went to the Staff Club, whilst Europeans scarcely ever went to the many seaside open bars, which littered the island almost as much as the empty and rusty beer cans they generated. I used to frequent Bill’s Bar a fair bit, however – it was owned and often operated by one of the island’s medical practitioners.

Then there was Nauru Secondary School.

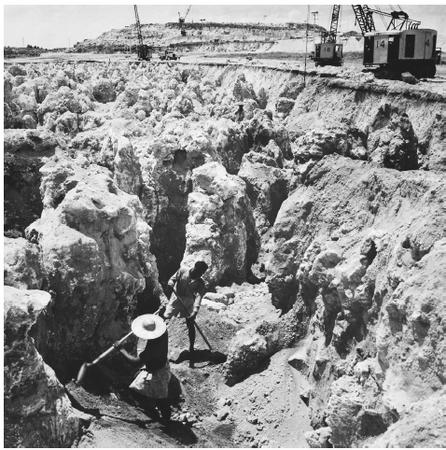

I was “given” 2B, 2C, 2D and 2E. 2E was very much what they sounded like. All classes were a mixture of Nauruans, Kiribats and Tuvaluans - with a few Europeans thrown in. The Kiribats and Tuvaluans were the children of the labourers on Topside (the phosphate diggings on the central, barren plateau of Nauru). They were often the hardest working: they had more to gain, for they had to return to their own economically poorer islands and any education was an advantage to them as scholarships could go their way. Their parents bore the brunt of poor living conditions on the island – they often had small flats with no power and water (and more recently, during a few economically destitute years in the Republic, they had no money either, as there has been none to paid them - nor to the white expatriates, for that matter).

As for the Nauruan students – they covered a wide spectrum, although the most academically left on scholarships to Australia, and the scions of the wealthy elite (generally politicians) were sent away to study in expensive boarding schools. That left some very bright and very diligent students, some bright and diffident students, some bright and psychologically ‘maladjusted’ students, and some non-existent students. This latter group was the quite large truant student body. I saw one pupil attend class only twice during the entire time I was at the school.

Always it was hot. Only the science ‘labs’ sometimes had air conditioning. There was no one room for me that first year. I had to chug my way around various, often dilapidated, often filthy classrooms, with the few resources that made any relevant sense, or that were complete. I stumbled over the truant student body in all manner of bizarre places, often with a disgruntled teacher or Acting Principal/Acting Deputy Principal (everyone in Nauru seemed to be ‘acting’ something or other!) in hot pursuit – sometimes through and over the graders and trucks and diggers in the adjacent Ministry of Works. Discipline, at least initially, was through physical intimidation. Nauruans respected strength and ‘macho man’ tendencies.

And always, right outside the school, was the airstrip. Everything stopped as we watched planes rumble on and off the tarmac, whilst we, perspiring profusely, wondered if this would be the plane that didn’t actually land or take off on time.

There was no curriculum. Several times, attempts were made to get something started, but they all failed due to staff turnover of about 20 expatriates a year, a turnover which was itself due to natural terminations of contracts, enforced terminations of contract, resignation, and in one case sheer insanity - a New Zealand teacher who had been banned from teaching in his home country had to be strait-jacketed onto an awaiting aeroplane. Local teachers were few and far between and only three or four at any given time had ever been ‘trained’. (Eventually, at least at Primary level, a Nauru curriculum was introduced.)

More than this though, the curriculum failure was due to the fact that those at the top were unwilling to take effective control. The Nauruan hierarchy wanted, or had been persuaded to support, a system based on the one that operated in the Australian state of Victoria, as many of them had won their own scholarships to that state in their early years.

But the Victorian system was irrelevant to Nauru, and in particular to its one secondary school and the one private Catholic Kayser College. What was called for was a uniquely Nauruan curriculum, incorporating, for example, Nauruan language, which was slowly being lost along with other aspects of the culture like songs, dance and weaving. Indeed the Nauruan language was then scarcely extant in any comprehensive written form.

There were infrequent examinations and reports. There was officially no corporal punishment: the Principal’s only official, and ‘ultimate’ punishment was a one-hour suspension! There was, at times, chronic vandalism of the classrooms – inside and out. There were no playing fields, no gymnasium. There was frequent theft of equipment from most departments – not always by students, as certain expatriates hoarded and dispatched large treasure troves homewards. There were occasional physical threats, and once or twice these came from pupils against staff. Because of the constant toing-and-froing of Headmasters – including the guy who had greeted me –there was often no leadership.

In my two-and-a-bit-year stint, there were five Principals or Acting ones or Deputy ones – everyone had a turn, even me, by my second year, when I was already H.O.D. of English (my predecessor in that role, the wife of the Principal who met me, had found everything “too hot”). Everyone had a turn. Some were efficient, some the complete opposite. We, as a staff, never really knew what was going on. Dawson Murray, for example, arrived mid-1980 and immediately the whole school (remembering that the other schools on Nauru, i.e. infant and primary, were mirror images of Nauru Secondary School) took on a more positive tone. N.S.S was repainted, repaired and its ‘difficult’ pupils were dealt with. However, Dawson was sacked quite soon afterwards for ostensibly being too critical, and maintaining too high a profile.

The Nauruans are a proud people and, after years of sublimation by Europeans - initially by Germans and later by Britons, Australians and New Zealanders - they were independent, and felt no desire to have their former ‘masters’ and plunderers of the phosphate criticise, albeit helpfully, their system or lack of it.

After Dawson went, having been given two days’ notice (as were others later), things returned to the norm of absenteeism amongst pupils and staff, and the frustrations of trying to get some guidelines from senior administration in the Government offices right next door. We returned to coping as best we could. Remember that English was the second language for most pupils and the first for most of the staff: some pupils were illiterate in English.

Yet there was a good deal on the positive side. There was some quite outstanding work from many pupils and some overseas trips of great worth. There were excellent athletics competitions on Topside, Round the Island Relays, and swimming competitions. House rivalry was intense and in the choral competitions everyone gave their best. And there was also an extremely generous annual budget allocation. (Of course, nowadays, with phosphate royalties drying up and all the investments from them squandered and mortgaged to the hilt, there is insufficient money for education.)

By the end of our first year, we had come to grips with the ‘way of life’. School wasn’t too bad and the money – comparatively – was good, so we bought bourgeois possessions like a new car, a waterbed, a new stereo, exotic furniture and so on. There was no import duty or sales tax and consequently plenty of kitsch things to spend one’s money on. We could go to the ‘beach’, in reality a bulldozed channel through the rocks, or go snorkeling over the reef to the tepid deeps. There was plenty of socialising and copious parties, although it was noticeable that there was little intermingling with the local community, other than getting Kiribati baby-sitters. The mail order catalogues were abundant and the houses weren’t too bad. One either adjusted or blew up and got off the island as soon as one could, although many expatriates had overextended themselves financially and were thus forced to stay longer than they would have liked. (At least they knew they would be paid – it is far different there now!)

Still, there were also quite arbitrary contract changes, one of which ensued at the end of 1979 when the contractually assigned three months’ leave was cut back to two months. If we didn’t accept this we were ‘down the road’. Some took that route, thankful for their escape. Over 8,000 people on a tiny island can indeed get to you and we were only manuhiri (guests) after all!

As noted earlier, I became Coordinator of English in 1980, mainly because I was the only suitable applicant for the position and I had to draw up the school timetable for that year. It needed constant restructuring, however, due to class closures and staff disappearances. Here I was, at 26, being involved in aspects of school administration that I would not have been exposed to, nor involved with, in a New Zealand situation for years or, indeed, at all. Bizarre? No, not really – this was just Nauru.

And this is the crux of the whole matter.

You see, there were/are always two cultures rubbing against each other in every aspect of life on Nauru Island. Over the years I have noticed similar culture clashes in stints in other places, such as Brunei Darussalam, UAE, PR China, Hong Kong and the East Coast of Aotearoa-New Zealand.

On Nauru, the disparate cultures rarely gelled. There was a contrast between on the one hand the WASP New Zealand culture of most of the teaching staff and their heritage of British-styled exams, curriculum, discipline, resources and on the other hand the far more laid-back resignation of the students, the few Nauruan staff, and the educational hierarchy. Here were two distinctly different ways of seeing, conceptualizing, prioritizing, of Being.

The Nauruans had seen Europeans – and the odd Maori – come and go forever. They (the Nauruans) were still there. It was always hot and siesta time was a daily event. They were – then – generally well off, although the phosphate royalties by no means trickled down to all Nauruan families and there was – even then – resentment that Europeans had taken a lot from the island prior to Independence – and since, unfortunately. By the time I left, hostility toward expatriates was growing increasingly manifest. They were, in some cases quite justifiably, the scapegoats. The fact that among the Nauruan youth were some extremely competent future leaders who were not being catered for, just didn’t seem to hit home. “It doesn’t matter” was the expats’ catchcall.

I left in 1981, a wiser chap. I learned from mates still there into 1982 and beyond some grotesque stories about the Principal’s car being burnt out and more two-day notices and so on. I wondered for a while if the English Department still had peeling walls and if they had new holes in them … But then Nauru receded in my mind as I strove to do other things and I had a whole raft of other experiences in other places.

First published in the PPTA Journal, Term 3, 1983, pp. 30-33.

My father informed me last night that his boyhood friend Winston Peters is about to hold an election rally out Franklin way, in some war memorial hall or bowls club. "Busloads of old people are coming up here from Tauranga" Dad reported. "The buses will have a reduced capacity, of course, because of all those wheelchairs and oxygen machines they'll have to fit in. And I guess Winston will have to organise ambulances to wait outside the venue, because some of his supporters are liable to collapse with excitement or fatigue."

My father informed me last night that his boyhood friend Winston Peters is about to hold an election rally out Franklin way, in some war memorial hall or bowls club. "Busloads of old people are coming up here from Tauranga" Dad reported. "The buses will have a reduced capacity, of course, because of all those wheelchairs and oxygen machines they'll have to fit in. And I guess Winston will have to organise ambulances to wait outside the venue, because some of his supporters are liable to collapse with excitement or fatigue."