(Mis)understanding 1951

Once again this blog is off the political pace. While Chris Trotter has been banging out an open letter to David Shearer, appealing to the Bible as well as to the shadow of Harry Holland in an effort to get the newly minted Labour leader to support Auckland wharfies in their battle against union-busters, I've been wandering through the virtual forest that is Papers Past, looking for connections between the Zeppelin Scare that beset New Zealand for a couple of months in 1909 and the transition from villa to bungalow housing in East Hamilton in the first half of the twentieth century.

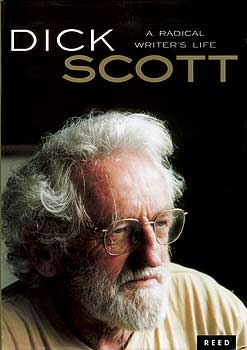

Once again this blog is off the political pace. While Chris Trotter has been banging out an open letter to David Shearer, appealing to the Bible as well as to the shadow of Harry Holland in an effort to get the newly minted Labour leader to support Auckland wharfies in their battle against union-busters, I've been wandering through the virtual forest that is Papers Past, looking for connections between the Zeppelin Scare that beset New Zealand for a couple of months in 1909 and the transition from villa to bungalow housing in East Hamilton in the first half of the twentieth century. Encouraged by Chris's talk of parallels between the present dispute on the wharves and the Waterfront lockout of 1951, not to mention the Great Strike of 1913, I thought I'd dig out a review I wrote, all the way back in 2001, of Anna Green's study of the drama of 1951. I was discomforted, though, when I took a look at the review, which appeared in the now-defunct Marxist journal revolution. My criticisms of Green's book seemed reasonable enough, but my almost unrelenting defence of Dick Scott's 151 Days, an insider's account of the lockout published by the Communist Party soon after the end of the struggle, seems a little quixotic.

While Scott fought on the side of the angels in 1951, his rambling, incorrigibly subjective book can hardly be considered the final word on the lockout. The emotive early pages of his tome, which seek to present the 1951 battle as the simple continuation of an unbroken history of class struggle stretching back all the way to the Wakefield settlements, are particularly problematic. By cherrypicking examples of heroic workers' struggle and ignoring counterexamples of apathy, cross-class collaboration against Maori and other minorities like Chinese, and intra-working class conflict, Scott offers up a quite misleading image of this country's history.

Although Scott never admitted it, and perhaps never even realised it, his first book was contradicted by many of his subsequent productions. His important studies of colonial brutality at Parihaka and in the Cooks and Niue, for instance, show quite clearly the extent to which Pakeha of all classes could identify with each other, in opposition to Polynesians. 151 Days began with an account of a strike by workers in the Wakefield settlement of New Plymouth, but Ask that Mountain showed that the Pakeha workers and small farmers of Taranaki were complicit in the smashing of the Parihaka commune in the early 1880s. In Would a Good Man Die?, Scott shows how a horny-handed son of the Pakeha working class created a police state on Niue in the name of colonial munificence, and was eventually assasinated for his troubles.

My review of Green's book was written at a time when South Island wharfies were resisting an attempt to casualise their jobs. I knew a number of people who were standing on picket lines in places like Port Chalmers, and I remember writing one or two agitational articles about the dispute for the far left press. At the same time, I was contemplating doing a PhD, and getting interested in the idea of digging out a few archives. I was trying to balance an enthusiasm for political activism and agitational literature with a growing interest in and respect for scholarship, and the result was an odd mixture of political and scholarly, or pseudo-scholarly, arguments.

I criticised Anna Green for having a social democratic, and therefore reformist worldview - but I was not content with making the normal far left political criticism of such a position. I linked her reformism to what I saw as her failure to organise her empirical research into the 1951 dispute around an hypothesis - a 'big idea'. And I tried to ennoble Dick Scott's first book by disguising its unsustainably heroic narrative of New Zealand working class history as a 'bold' and 'robust' 'hypothesis'.

I might have defended parts of 151 Days in detail, but I felt it best to pass other sections over in silence. The Communist Party had been badly damaged by Stalinism and its cultural tentacle, Zhdanovism, by the early 1950s, and Scott's text was at times as full of philistinism and national chauvinism as an issue of The Truth. After Uncle Joe had told them that postwar New Zealand was being colonised culturally as well as economically by the United States, the Communist Party had decided, presumably against the advice of the long-suffering RAK Mason, to campaign against such symptoms of decadent imperialist culture as Abstract Expressionist painting, comic strips, and jazz. Scott's book concludes, not with a tribute to the workers who fought so hard against Sid Holland in 1951, but with a rant about the role comics were playing in the corruption of Kiwi youth. Why Scott didn't excise such passages when his book was reissued in 2001 I don't know.

I might have defended parts of 151 Days in detail, but I felt it best to pass other sections over in silence. The Communist Party had been badly damaged by Stalinism and its cultural tentacle, Zhdanovism, by the early 1950s, and Scott's text was at times as full of philistinism and national chauvinism as an issue of The Truth. After Uncle Joe had told them that postwar New Zealand was being colonised culturally as well as economically by the United States, the Communist Party had decided, presumably against the advice of the long-suffering RAK Mason, to campaign against such symptoms of decadent imperialist culture as Abstract Expressionist painting, comic strips, and jazz. Scott's book concludes, not with a tribute to the workers who fought so hard against Sid Holland in 1951, but with a rant about the role comics were playing in the corruption of Kiwi youth. Why Scott didn't excise such passages when his book was reissued in 2001 I don't know. I still had the notion, a decade ago, that scholarship could only be satisfactory if it were linked to political agitation. Without the discipline of activism, and the need to convert piles of data and abstruse theorising into hard-hitting articles and leaflets, the scholar was, I thought, doomed to go off the rails, and become politically and intellectually suspect. It never occurred to me that my demand for political purity amongst scholars might be a way of insulating myself against difficult arguments, or that the past might be important precisely because it wasn't always 'relevant' to the present - wasn't, in other words, immediately convertible into some snappy lesson in political morality.

It was not possible for me to understand, in 2001, that an avowedly apolitical historian had recently published a powerful and heretical interpretation of the past Dick Scott was content to romanticise. Miles Fairburn's book The Ideal Society and Its Enemies overthrew all the smug pieties of both revoluationary socialists like Dick Scott and liberal nationalists like Keith Sinclair and Erik Olssen, by insisting that, for Pakeha at least, the nineteenth century and early twentieth century were characterised not by mateship and the beginnings of the road to the welfare state, but rather by an almost misanthropic individualism.

Fairburn's version of the nineteenth century has been condemned by many lefties, because it seems to make events like the Great Strike of 1913 and the lockout of 1951 into aberrations. Ultimately, though, and no matter what Howard Zinn and his local avatars have said, the left is better served by accurate interpretations than by sentimental stories. Perhaps comrade Fairburn will produce a study of the 1951 lockout?

Now that I've disowned it, here's that text from 2001...

British Capital, Antipodean Labour: Working the New Zealand Waterfront, by Anna Green (University of Otago Press, 2001)

Perhaps Anna Green is brave to write a history of an event as contemporary as the 1951 Lockout.* The fiftieth anniversary of the Lockout has been marked by a number of reunions, several public meetings, numerous arguments over talkback radio and dinner tables, and a major conference featuring, amongst other things, the launch of British Capital, Antipodean Labour.

Though some of the backward glances have no doubt been prompted by the anti-casualisation struggle currently being waged on the South Island waterfront, the great Lockout and the strikes that flared up around it have always been a fount of division and inspiration for New Zealanders: a source of argument, a store of legend and anecdote, and a litmus test for leftists. I even know a sad old man who, as an excessively idealistic teenager, broke up with his girlfriend over the issue! It might seem, then, that 1951 is a piece of their history that New Zealanders take too seriously to leave to historians.

Perhaps the choppy waters surrounding the subject of 1951 seemed inviting to Anna Green when she began, in the late 1980s, to research the PhD that forms the basis of British Capital, Antipodean Labour. After all, what budding Kiwi historian wouldn’t want ‘Sorted out 51’ on their CV? To take a subject surrounded by superheated debate, and coolly research it into clear focus - that’s the mission statement of British Capital, Antipodean Labour. For Green, good academic history is to be wrested from polemic, from the 'myths of New Zealand labour historiography'.

To understand Green’s book, then, we have to understand the academic enterprise it advertises. There’s something touching about the image of The Historian, seated in an unnaturally quiet room, leafing intently through piles of indecently obscure

documents. Of course, historians haven’t always been everyone’s favourite pedants: Herodotus, the founder of the genre, was justly dubbed ‘the Father of Lies’, and many of his disciples have been too concerned with the truth to be all that bothered with facts. It was the Victorians, that race of collectors, who came up with the idea of the historian as fact-finder and storer, and were able to imagine an ‘Ultimate History’, the results of the labours of generations of historians, which might contain all the facts of history, and nothing else.

The Victorian creed of pedantry took a few hits in the twentieth century, when pesky philosophers of history showed up on the academic scene with awkward questions about awkward terms like the fact-value distinction and the theory-dependence of observation, but managed eventually to resurrect itself in a doctrine often called ‘social’ or ‘grassroots’ history.

Although it has frequently posed as a new ‘history from below’, enamoured of the minutae of the lives of the members of that mythical race, ‘ordinary people’, social history has often been afflicted by very Victorian hang-ups about the sanctity of facts, and the sinfulness of ‘speculation’. Like its dour grandmother, social history tends to blush at the idea of constructing a ‘big picture’ of long-term historical trends to complement its detailed sketches of individual pieces of the past.

Cautious in tone, ultra-empirical in methodology, and studiously myopic, British Capital, Antipodean Labour seems to me to be a graduate of the school of social

history. And it should not be thought that all Green’s toil have been in vain: she has unearthed, with admirable care, some fascinating and potentially quite useful information about the world of the New Zealand waterfront up until 1951. Interviews with dozens of ageing seagulls and an inspection of the archives of British shipping companies have been especially fruitful. As a result of these labours, we now have a picture of the great extent of the wharfies’ use of what Green calls ‘informal resistance’ (clue: Sid Holland would call it lounging and stealing), not to mention a powerful impression of the amorality of the British-based shipping companies that gave the wharfies most of their work.

The irony of British Capital, Antipodean Labour, and the thing that makes it so irritating to read, is the fact that Green’s methodology cannot deal with

the implications of the subject-matter it has unearthed in such quantities. To put it bluntly, Green’s book tells us how, but does not tell us why. Her close-up focus

is great for revealing detail, but she is unable to make sense of that detail by putting it in the perspective that only a long shot can provide. Consider the following passage, from the book’s introduction, where Green makes a rare foray into the dangerous realm of historiography:

Undoubtedly, the waterfront dispute had far wider consequences than most industrial conflicts...Two myths of New Zealand’s labour historiography have shaped rival interpretations. The first, the dominant liberal left myth, is informed by a dichotomy of struggle between labour militants and moderates. From this perspective, the militants who controlled the watersiders’ union in 1951 rejected arbitration, thereby unwisely challenging the power of the state, and as a consequence destroyed both the union, and public confidence in the Labour party....The second - socialist - myth derives from that deep vein of millennial thought in which a heroic working class fights to create socialism.

As Dick Scott explained in the introduction to his book on 1951, ‘...the task, as I saw it in the circumstances, was to record all that positive in the great struggle, all that has gone to enrich our brave traditions’...neither myth, as advanced in the previous literature, provides an adequate explanation for the events of 1951. The dispute did not emerge from a vacuum, but exploded after a long period of conflict.

One wonders how Green can claim that Dick Scott did not recognise the 'long period of conflict' that preceded the explosion of 1951, if the Dick Scott she talks about is indeed the same Dick Scott who wrote 151 Days, the first and best extended treatment of the 1951 Lockout. After all, Scott’s tumultuous narrative

begins not in 1951 but in 1841, with an account of a strike, possibly this country’s first, by New Zealand Company employees in the miserable new settlement of New Plymouth. Scott was a member of the Communist Party of New Zealand when he wrote 151 Days, and his book is suffused with ideas of the eternal conflict of interest between worker and boss, and the necessity of class struggle.

Surely Green does not think that the 'brave traditions' referred to in 151 Days exclude the stoushes on the Kiwi waterfront in the decades before 1951? It is in fact Green, and not Scott, who has difficulty in giving a sense of historical perspective to 1951 and its precursors. We can this see this much when we consider the sentence which follows those quoted above:

In seeking to explain the abysmal labour relations on the waterfront, it is essential to to examine the labour process on the wharves: the nature of the work and the way in which it was organised by the employers, for it is here that so

much of the conflict began.

Encountering this sentence, I immediately wanted to ask ‘Why did the work take on the particular nature it had?’ and ‘Why did the employers organise the work in the ways that they did?’ In other words, why did the employers try to get total control of the wharfies’ work, and make them work in such dirty, dangerous conditions?'

Unlike Green, Scott had answers to these questions - he saw the capitalist drive for profits, and the alleged fact that increased profits could only come from the increased exploitation of labour, as the reasons for control freak shipping companies making wharfies risk their lives in filthy conditions. In giving these answers, he relied on a big historical picture, which was the product of the analysis of, amongst other things, many other specimens of industrial conflict, to make the sense of the details of the conflict on New Zealand’s waterfront.

I am not suggesting that Scott’s is the only sensible possible treatment of the 1951 Lockout and the conflicts that preceded it; rather, I am arguing that Green’s research has been insufficiently informed by the sort of hypothesis - I have been calling it a ‘big picture’ - that might be able to illuminate the facts she has unearthed. It’s all very well to collect facts, but facts need the explanation that can only be provided by a sophisticated hypothesis - a hypothesis which of course ought to be open to falsification and modification. Part of the problem for Green is thatthe details her close ups capture are so extraordinary and controversial that, for the New Zealand reader at least, they demand an explanation of the type she seems most reluctant to give.

Unwilling to explain it with reference to something exterior to it, Green tends to mystify aspects of her subject matter. In the pseudo-explanation of waterfront conflict quoted above, for instance, Green mystifies the features of her ‘labour process’. The “nature of the work” and the way that the work 'was organised by employers' cannot serve as explanations for the struggles between wharfies and employers, simply because they are effects of that struggle. As new evidence unearthed by Green shows, the dirty and dangerous nature of waterfront work was the product of employer penny-pinching, not any immanent quality of that work.

Similarly, the relentless attempts of the shipping companies to exert total control over wharfies’ work were the product of their own obsessive drive for efficiency on the waterfront, not any abstract necessary condition for a functioning waterfront.

Like the crude environmentalist who fingers technology as the ‘cause’ of pollution, neglecting to mention the social relations that govern the use of technology in capitalist society, Green blames the features of the ‘labour process’ for conflict on the waterfront, when these features were the product of a set of social relations, viz. the relationship between wharfies and their employers. Any examination of this relationship would lead away from her immediate subject matter into an examination of the wider historical world which gave this relationship its shape, and is thus off limits.

When the new subject matter she presents pushes especially urgently towards generalisation, Green resorts to conceptual hi-jinks in an effort to neutralise its implications. The title of her book reflects her introduction of a supposed “third party” - the British-based shipping companies - into the “old story” of waterfront conflict between workers and the state. By presenting ‘British Capital’ as having interests which importantly contradict those of Sid Holland’s government and its Kiwi capitalist supporters, Green attempts to prevent the evidence she has unearthed for the contradictory interests of shipping companies and wharfies being mobilised as evidence for a class struggle-centred account of waterfront conflict. If Dick Scott had had access to all Green’s material showing the shipping companies’ hatred for the wharfies, and of the contradictory interests that formed this hatred, he would have happily (too happily, perhaps) counted it as yet more evidence for his picture of 1951 and its precursors as a confrontation between two classes with hopelessly contradictory interests. After all, the British capitalists and the Kiwi capitalists were both members of the same class, weren’t they? However much they might disagree over issues like port charges and taxation, the British and Kiwi capitalists had a fine common cause in their war against the wharfies. Both, after all, had a huge interest in the efficient functioning of the ports of the old British empire.

The whole conception of ‘Kiwi capitalists’ as distinct from ‘British capitalists’ seems slightly dubious when applied to the first half of the twentieth century. Only a few decades before the period Green studies Britons had created capitalism in New Zealand, bankrolling the development of the country’s productive forces.

The emergent capitalist class in New Zealand retained very close ties to the class of the 'Mother Country', investing shares in its companies and offspring in its universities. It is by no means obvious that the two groups grew far apart in the first half of the twentieth century. Green can only ignore the huge importance of the common interests of Kiwi and British capital, and thereby keep her ‘discovery’ of a “third party” viable, because of her refusal to consider her subject in terms of anything exterior to it. By treating the force of capital in an ahistorical way, i.e. by isolating it in the narrow focus of the New Zealand waterfront in the years between 1915 and 1951, she is able to split it along national lines, and distort a conflict that fundamentally contained only two parties.

Another of Green’s conceptual hi-jinks involves the treatment of the ‘informal resistance’ offered by wharfies to the shipping companies’ work regime. British Capital, Antipodean Labour offers up fascinating evidence of such practices as spelling (rotated ‘loafing’ on the job), gliding (leaving the job early) and theft, and shows that they were forms of direct industrial action. Green is anxious, however, to assert the ultimate futility of informal resistance: according to her, it undermined attempts by some union bosses to gain 'workers’ control' of the waterfront by more formal means.

Green’s 'workers’ control' is a rather miserable predecessor of the ‘partnership model’ of worker-boss relationships championed in the 1980s and early '90s by the likes ofKen Douglas. 'Workers’ control' of the waterfront was thankfully rejected by Jock Barnes and the left wing of the wharfies’ union, and junked after 1947. In

a revealing passage, Green quotes a pitch for 'workers’ control' made to the shipping companies by union bureaucrat Nigel Roberts in the early 40s:

If we can get control of the job we will be the responsible ones to fire them [‘troublesome watersiders’] out. Our trouble today is that we cannot get rid of them because we are not the employers. Make us the employer and we will see that they play the game...

Commenting on Roberts’ words, Green claims that 'The contradiction between strategies of resistance and self-management [i.e. in Green’s book, ‘workers’

control’] could not have been more clearly expressed'. Here Green’s notion that grassroots rebellion on the wharves and the managerial ambitions of Roberts were strategies in pursuit of the same aim is truly absurd: informal resistance and Roberts’ ‘workers’ control’ were not different routes to the same port, but different routes to entirely different ports. Unable to escape the confines of her subject matter byimagining a genuine case of workers’ control, Greens ends up betraying the implications of the material she has uncovered on informal resistance.

In summary, then, the extreme measures British Capital, Antipodean Labour takes to accommodate the events of 1951 within the paradigm of naively empirical social history end up making it a confusing and unsatisfying read. Many of New Zealand’s social scientists get away with naive empiricism, but Green has chosen a subject which is too demanding of such a technique. 1951 was a year in which extraordinary things happened - a year in which the basic, usually hidden features of New Zealand society suddenly showed themselves with a frightening clarity in the form of Sid Holland’s short-lived police state and the opposition it so effectively crushed. For the pamphleteers in prison and the marchers on the end of long batons, the need for a big picture to explain very big, almost unimaginable events was only too clear. It was people like these who, a year after the end of the Lockout, bought out the first edition of Dick Scott’s 151 Days . Despite its flaws Scott’s book managed to open up a real historical perspective on the waterfront war, offering an extraordinary explanation for extraordinary events. Can Anna Green’s book, full as it is with new-found facts, offer half as much understanding of its subject as 151 Days?

* Green would no doubt argue that her book is about far more than just the 1951 Lockout: it is, afterall, subtitled Working the New Zealand Waterfront, 1915-1951, and deals with the world of the waterfront during those years inconsiderable detail. In my opinion, however, the whole of the book is orientated toward the year 1951, and its pre-1951 material is intended primarily to throw light upon the events of that year.

12 Comments:

If I may paraphrase the famous cartoon exchange between two World War I soldiers cowering in a shell hole in no-man's land:

"If you know of a better myth, Scott, go to it."

what chris said. there are no truths inthe class struggle.

I can see the point you're making, Chris. It's a bit rich for eggheads to come along and retrospectively pass judgment on workers like the wharfies fighting for their livelihoods against the might of a state acting entirely in the interests of employers.

I remember a situation which occured in the midst of the mass anti-war movement of 2002-2003. A distinguished intellectual announced that he was no longer going to grace protest marches and forums with his presence, because protesters had begun chanting denunciations of Bush's 'fascism'. He made the point, which was in isolation quite valid, that Bush wasn't a fascist, and that the word shouldn't be used so loosely. But he should have recognised that, in the supercharged atmosphere of massive marches and sieges of the US Consulate, where protesters confronted police and expressed their anguish at the coming assault on Iraq, the precise use of language and concepts went out the window.

And yet I can't read Dick Scott's book without continually saying 'But hold on...', 'Steady on mate...', 'Are you sure about that?' Are we supposed to abandon all criticisms of a man's work, just because he played a heroic role in a heroic struggle?

And mightn't the wharfies have gained something from intellectuals like RAK Mason, Dick Scott, and Sid Scott in 1951, if those intellectuals hadn't meekly towed the Communist Party line, and had instead worked out their own analysis (or analyses) of the situation the workers faced?

Sid Scott admitted in a 2001 interview that Jock Barnes had no strategy at all for winning the confrontation of 1951 - he simply thought from day to day. And the Communist Party's Moscow-dictated worldview, which failed to take any account of local New Zealand conditions, wasn't much more useful than Banres' pragmatism.

I don't agree Dave Bedggood on quite a few subjects, but he has written some interesting articles about both the 1913 Great Strike and the 1951 Lockout. Dave, who - like me - grew up on a dairy farm in a conservative part of the countryside, is well aware of the isolation of both the Red Feds and the Waterside Workers Union in the context of wider New Zealand society. He talks about the tragic way that farmers, many of whom shared some interests with the wharfies, were used to smash the 1913 strike and were enlisted as supporters for the state's crackdown in 1951, and discusses whether there might have been some way that they could realistically have been induced to side with the workers against employers.

I think some of the points Dave raises are worth thinking about today, when Fonterra, that grotesque parody of a farmers' cooperative, is backing the Ports of Auckland against the wharfies. Above all, I think, the tendency of populist left-wing historians to cherrypick the heroic bits of the past and ignore conservative trends and reactionary episodes should be questioned. Heroic but selective narratives really are counterproductive.

'Intellectuals who can't cut sugarcane should be asked to leave Cuba'

- Che Guevara

why pick on scott's hate of comics. it is not the most important part of his book.

Your original review is still good.

I have only a cheap edition of '151 Days' (probably from 'The Progressive Book Shop'). It doesn't mention anything about comics as far as I can see, but to my shame I've never read it right through. I must do so.

In spirit, Dick Scott was on the right track.

The US [Imperialists] are fascists, let's face it. The basic lessons of 1951 etc are still very valid.

(As Chris Trotters campaign shows).

Here's some old notes collected for an educational I did at Occupy Auckland at the end of November as part of the Free University initiative.

http://situationsvacant.wordpress.com/2011/11/30/the-1951-lockout-of-port-workers-lasted-151-days/

Hi Richard,

I think Dick Scott is pointing in the right direction when he blames the Lockout of 1951 partly on pressure from the United States, which was fighting the Soviet bloc in Korea and persecuting anyone to the left of Eugene McCarthy at home. The US wanted to see the destruction of left-wing trade unions throughout the West, because it saw these organisations as potential enemies in a 'Cold War' which had in a few years become very heated indeed.

What I object to is Scott's attempt to marry opposition to US government policies to rejection of postwar avant-garde culture. His denunciation of US comic books was one expression of a much wider Communist Party campaign against such symptoms of decadent capitalism as jazz, Abstract Expressionism, and modernist poetry.

In Britain, the young EP Thompson was dragged in to these campaigns, as local Communist Party bosses acted on the instructions of Stalin's culture tsar, Zhdanov, and purged modernism from their party press. The middle-aged Thompson wrote a sorrowful essay about the campaign against Edgell Rickword, the communist poet and literary critic who was responsible in the '20s and '30s for bringing Rimbaud, amongst other modernist masters, to the attention of the British public for the first time. Rickword was blackballed because he didn't write rhyming quatrains about the glories of Stalin's slave labour schemes.

A similar philistinism took hold here, and for a time turned intellectuals like RAK Mason, Elsie Locke, and Sid Scott into party drones.

The communist campaign against avant-garde trends in culture put it in bed with some of the most conservative elements of New Zealand society. American comics, for instance, were a preoccupation of the right-wing scaremongers who congregated in publications like The Truth - the sort of people who made 'bodgies' into a scare word

in the '50s and warned about the perils of milk bars.

Roger Horrocks wrote an interesting essay for the '80s literary journal And about the stigma associated with being a fan of comics during his childhood in the 1950s...

Yes I agree with that. Re Scotts's book (or the edition I have) it is certainly quite brilliant and inspiring.

That issues of a degree of Philistinism (or Economism versus Politics in Unions and other issues) in the Communist parties etc was there when I debated with say Frank Lane in 1970 or so at PYM meetings or elsewhere, and also we had many discussions on the problem of unions, of theory versus action and much else.

Frank was strongly critical of, fro example, Bill Lee's [he was the leader of the PYM and in the Communist Party] scorn of theory. Dick Fowler was also seen as [too much of a] theoretician. Shadbolt, who had great charisma huge oratorial skills, and was very active and courageous in direct actions, was not really involved in such debate of theory. He acted more as an individualist (but he certainly knew about work as he worked on power projects (where work was hard and dangerous). Bill Lee worked for some time at the Railway Workshops as I did.

I was in the Freezing works union at Hellabies where, paradoxically my father was a "boss" in their Head Office (which is why I got jobs there pretty easily in the first stage); but then I started taking part in politics (union and propaganda against the Vietnam war atrocities etc) after few seasons and they were in a dilemma. Dick Scott also wrote a book about Hellabies. My father doesn't appear in it but I recognize a number of union blokes and also the Engineer and so on, and when I was about 10 Alan Hellaby gave me a book about art practice which I keep to this day.

These situations are complex. We also realized that a mix of popular culture and other culture and ideas was needed but some of the Communist Party people such as Len were dubious of what they called "Bourgeois culture". We shared some of that attitude, but not entirely. At a filming of War and Peace Len came out with his "individualist views of history" and so on...it was as if he couldn't appreciate or learn from the film because of a formula (and Len I always found to be very good);and he had to bring dogma into it. There were also problems with rhetoric and soon. (But rhetoric is always somewhat necessary.) We had many discussions on the role of theory and practice at the time.

Roger Fowler and others formed a Peoples Union to buy food in bulk and we fought for Mrs Martinac (an old resident in central Auckland whao was threatened with eviction with many others who were only paid Government valuation as compensation for their homes...we worked together with local people and got her an equivalent and even better home withe help of a lawyer (Williams). Meanwhile Betty Walk helped organize the Tenant's Protection Association. I also visited Paremoremo. 123 Ponsonby Road started by the Lanes (of - at one time - the Australian Communist Party) had the idea of integrating and mixing with local working class people, an idea taken from the writings of Mao tse Tung. We were influenced very much by those ideas and those of Lenin etc. Frank wanted to sell books of a wide range and then sold poster with including say pictures of Karl Marx, Malcom X, Black Panther movement people and Che Guevara - Jane Fonda, Jimi Hendrix (who was hugely popular then) and other "cultural icons". Films of both political import (from the USSR, China and Eastern Europe etc) and recent films were also shown.

The problem of revisionism etc was thrashed out. Also moral questions and even our own personal health, interests etc We, or at at least I, had no illusions about Vietnam, the USSR, Cuba, or China. But revolutions there and events in the world inspired us.

As to comics, my mother, hearing me talk of comics when I was a child, was angry (she was really never very angry, so "angry" for her was significant); and I developed a kind of aversion to them. (I still find it hard to read or like (or sometimes even understand) comics or "jokes" but in principle I "approve" of them as an addition to our total culture)* But I did like Donald Duck, Super man etc and of course we saw a lot of US culture (good and bad) at the "flicks". [Some of it included outright pro US Imperialist propaganda on the Korean war.] Frank's point partly was that from the mix and the totality of culture and the interaction of ideas ... all these things assisted the workers to develop ideas and "political consciousness. The "hippies" were into drugs and not often interested in the working class. There theory was weak in other directions...Marxism being low on the list, while vague ideas of "peace" and "love", and taking drugs etc, and so on, stood in for theory. For many of those in the Party though, the bottle made up for big part of their theory. I resisted total immersion and stayed outside the Communist Party, although at one stage I thought of joining.

It has some resonance with E P Thompson's dilemmas.

But this is not the whole picture.

But Scott's book (like maybe also writings of Lee) has a real value and is relevant to now.

I had a chance to meet Mason but never got to do so, I regret that.

*I think my mother and others saw them as somehow not "good" just as we are now critical of television (which was yet to come then!) videos and much of the recent developments in popular culture such as the Internet we are talking across!

But I am turning now toward or back to some NZ Political-Historical events so Dick's Scott's book is very absorbing. Exhilerating even.

Someone could well write a more extensive analysis of the time - perhaps Chris Trotter has done in his books?

And it is still very relevant especially with (union) action going on right now.

I completely agree with the 2012 essay. I don't know much about European history in NZ but it seems just like any other settler colonial state. The biggest contradiction in settler societies is colonialism, so obviously 'the left' won't succeed by pandering to colonial myths. I recently read Settlers by J Sakai apparently it is the same in America, the white left have romantic nostalgic ideas about the history of the labour movement but in reality the militant unionised workers were fighting to exclude African workers from factories or enrich themselves by stealing more Indian land etc. Romanticising white employees of the NZ Company (!) is another example! A lot of NZers have the same delusion as Americans that their country is somehow innocent or an example of enlightenment to the world, this myth is not even possibly revolutionary. The white working class in NZ have the same labour aristocracy or petty bourgeois consciousness as Americans, they obviously have a lot more to lose than their chains - for a start all the land and resources stolen from Indigenous people. I think it is VERY important to get rid of these myths, the reason the left in NZ and other western countries has failed is because they always fail to analyze the situaion correctly. If you are serious about class struggle then ignoring the reality of class and race in NZ society is counterproductive. We can't have a revolution based on lies or we will just be reinforcing colonialism.

The first comment used WWI as a metaphor, WWI was a war of competing imperialisms and both those soldiers died because of stupid romantic myths that covered up the reality they were fighting for imperial interests. They should have forgot the myths and fought against their own governments who sent them to die - like Lenin who actually managed to get his revolution off the ground.

I haven't read any of the books reviewed but I can see a "big idea" in Green's hypothesis that the 1951 was a result of competition between colonial NZ and UK capitalists. That makes sense as part of NZ's history.

And - I hate comics too I agree with Stalin! I wonder what Adorno would write about comic-reading hipster anarchists if he were alive.

Post a Comment

<< Home