Te Radar takes the missionary position, and screws up again

The second episode of Radar Across the Pacific confirmed Te Radar's fondness for cliche. Wandering around Tonga on a Sunday with his film crew, he noticed lots of shuttered shops, and lots of folks snoozing in public. Impressed by this display of somnolence, Te Radar decided that it reflected the profound influence of European missionaries on Tongan society. He conceded that Tonga was never formally colonised by Western powers in the nineteenth century, but claimed that missionaries from the Old World "certainly captured" the "hearts and minds" of Tongans.

But Sundays in Tonga are not all they might at first seem.

Towards the end of his episode, Te Radar chatted with Kalafi Moala, Tonga's most important journalist. Moala and Te Radar discussed Tonga's pro-democracy movement, rather than the keeping of the Sabbath, but if Te Radar had bothered to read his interlocutor's book In Search of the Friendly Islands he would have found a long description of the various ways in which Tongans flout the laws which prevent commercial activity on Sundays. Tongan shopfronts may be shuttered on the Lord's day, but locals know if they knock at a back door normal service will be provided. Moala notes that Tongans consume alcohol in large quantities on Sundays, whatever the law may say.

Nor were the Tongans Te Radar saw sleeping in public necessarily symptoms of a Sabbatarian zeal. Like many peoples who have not yet fully submitted to the exigencies of capitalism, Tongans do not always keep regular hours of work and rest, and do not feel ashamed about catching up on an hour or so of sleep in public, even if that means lying down in a slow-moving queue or on a piece of pavement. The folks Te Radar saw napping in broad daylight might have been recovering from a kava circle or a tapa-beating session, rather than abstaining from consciousness in the name of the Lord.

More important than Te Radar's misunderstanding of the Tongan Sunday, though, is his claim that the country was "captured" and virtually colonised by Western missionaries in the nineteenth century. No one can deny the massive influence of Christianity on Tonga over the past couple of centuries. The country's towns and villages are filled with churches, its flag is dominated by a cross, and its motto is 'God and Tonga are my inheritance'.

But too many observers tend to decide, like Te Radar, that Tongans simply fell on their knees in front of European missionaries in the nineteenth century, and passively submitted to a prepackaged version of the Christian doctrine. There is a good deal of condescension implicit in such an assumption.

We don't, after all, assume that the English Reformation of the sixteenth century was the result of Anglo-Saxons falling on their knees and accepting without question the gospel of Protestantism that John Hus, Martin Luther and others had forged on the European continent. We know that Protestant ideas were taken up and reworked by indigenous English theologians like John Wycliffe, and we know that Henry VIII turned the new doctrine to his own, deeply political purposes, as he restructured his society and increased his own power. Why should we assume that the priests and leaders of nineteenth Tonga were any more less crafty than their counterparts in sixteenth century England?

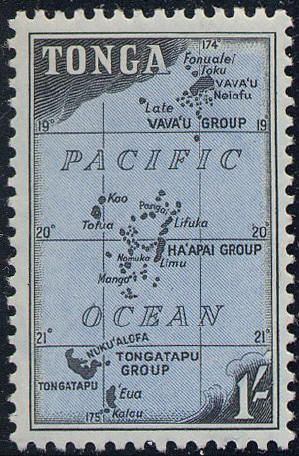

As the Dutch Marxist scholar Paul van der Grijp shows in his 2007 essay 'First Mission in Western Polynesian: the Dramatic Tongan Experience of the London Missionary Society', the initial attempt to evangelise the Friendly Islands was a disaster. The thirty young Britons who arrived on Tongatapu in 1796 soon got into serious trouble, thanks to their tedious sermons and their tendency to get involved in inter-village disputes. A missionary named George Vason grew so discouraged with the lack of progress that he threw away his dog collar and set about acquiring Tongan wives. After several of Vason's former colleagues became involuntary martyrs in a local war, the first attempt to Christianise Tonga came to an abrupt end.

It was Tongans, not Europeans, who planted Christianity permanently in the Friendly Islands. After smashing the statue of a pagan god with the trunk of a small tree and living to tell the tale, a Ha'apai chief named Taufa'ahau decided that the old gods of Tonga had lost their power, and that the new monotheistic doctrine ought to be embraced. After waging a series of holy wars, Taufa'ahau succeeded in unifying his country, and in 1845 he declared himself Tupou, the first king of modern Tonga. During his reign of five decades Tupou I was assisted by a number of palangi Methodists, including Shirley Baker, who helped draw up Tonga's revolutionary 1875 constitution and for a time served as the country's premier.

But Tupou I's alliance with Baker did not signify his subservience to European Christian authority. In the 1880s, after the Methodist church had begun to encourage Tupou to accept British colonisation, Baker denounced his superiors in London as shills for imperialism. After the Methodist hierarchy and its friends in the British Colonial Office demanded Baker's deportation from Tonga, Tupou announced that he was turning his back on 'foreign' Christianity and founding the Free Wesleyan Church. Like Henry VIII centuries earlier, Tupou made his break from foreign religious authority for essentially political reasons. Pro-British clergy were driven from Tonga, and the property of the old church was seized by the king.

Even before the 1880s, mainstream Methodism never had a monopoly on Christianity in Tonga. A Quaker named Daniel Wheeler had visited the country in 1836 and won widespread sympathy for his faith. In the 1840s Frenchmen had arrived with a relatively liberal brand of Catholicism, which encouraged rather than prohibited traditional dances and poems, and found followers amongst Tongans alienated from Tupou I's Protestantism. In the twentieth century Methodism spawned numerous offshoots, as Tongan theologians argued over obscure passages of the Bible, and Mormonism took root. New Christian denominations continue to be imported into Tonga. Recently the Russian Orthodox Church set up shop on 'Eua, the Kingdom's southernmost inhabited island.

It is clear that, just as the sixteenth century English assimilated Protestantism and adapted it to their various ends, so the Tongans of the nineteenth century seized hold of the Christian doctrine and reassembled it in ways that accorded with their traditions and interests. For the young Taufa'ahau of Ha'apai, Christianity was the dynamic new ideology which, when deployed alongside muskets and canon, could unify his country. For the elderly Tupou I, the perpetuation of the Christian faith meant the creation of a new, anti-imperialist church and the expulsion of English clergy from his realm. For Tupou's former pagan opponents, who had only belatedly and reluctantly become Christians, Catholicism offered a set of rituals reminiscent of some of the old heathen rites, as well as a relaxed attitude to pagan dances. The other denominations which began to appear in Tonga in the late nineteenth century represented other groups, with their own interests and agendas.

In a recent interview, Te Radar admitted that he didn't bother to do any research about the Pacific before he arrived in nations like Fiji and Tonga with his film crew. In the absence of any understanding of the history and sociology of the region, he is being forced back, in episode after episode, onto rather unsavoury stereotypes. Last week Te Radar offered us two versions of the noble savage myth; this week he recycled the cliche of the simple-minded Pacific Islander who succumbs easily to the missionary, and submits passively to European cultural imperialism. What cliche can we expect next week?

[Posted by Maps/Scott]