Greek crosses and invisible cats

Ellen spends most of her time painting and teaching painting at Elam School of Fine Arts, so it is not surprising that her book covers are marked by a painterly sense of colour and space. She favours subtle rather than garish colours, and is fascinated by the mists and vacuums that haunt old photographs. Her covers often seem to want to create a sense of intrigue, rather than to act as simple advertisements for the texts behind them.

The image on the cover of On Tongan Poetry was apparently pulled by Paul Janman from an old Helu family photo album, and is shown for a few seconds during one of the more tranquil, nostalgic passages of Tongan Ark.

Cats and dogs in Western Polynesia might have to forage for their food, but they seem to have certain rights unknown to their relatives in New Zealand. They seem to be able to go anywhere, and to be able to bark or meow as loudly as they like without ever being shushed up.

One of Jorge Luis Borges' stories describes a society where a man can, if he draws the right number from a lottery, be deemed invisible for a week, and thus wander wherever he pleases and do almost anything he likes. Because nobody is allowed to admit seeing him, a man who has been deemed invisible can go to the market and steal as much food as he or she likes, without fear of arrest and punishment.

I thought about Borges' story when I attended a service at the largest Catholic church in Apia, and watched a pale, skinny, scabby dog trot down the aisle between pews packed with worshippers, sit for a while at the foot at the pulpit where an extravagantly robed priest was giving a sermon in impassioned Samoan, then yawn and bark and trot back down the aisle and out of the church. Although a couple of palangi trourists like me guffawed at the dog, none of the Samoan worshippers so much as looked at the creature.

Futa Helu enjoyed winding up his countrymen by adopting odd foreign practices, and it's possible that he decided to keep a pet cat to raise the eyebrows of his neighbours. Given the extreme mobility of cats and dogs in Tonga, though, the moggy on the cover of the new book may have been a stranger that wandered into the frame with Futa for a few moments.

The flag adopted in 1864 showed a red cross at the centre of a field of white. After Tupou's flag began to be mistaken for the banner of a certain charitable organisation, though, a field of red was added, and the cross was moved.

When I saw a draft version of Ellen's cover I worried that its crosses might send out the wrong message about Futa Helu. Here's an e mail I sent to Brett Cross, the boss of Titus Books:

The cover looks great...The only potential problem that occurs to me is the use of the cross. Futa Helu was seen as a secularist foe of the intersection of the Tongan state and church - an intersection which is perhaps symbolised by the national flag - and the pagan poems, songs, and dances he championed sometimes raised the hackles of conservative Tongans. The poetic forms being discussed in the book all have their origins in pagan times. Given all this, is there an incongruity in the use of the cross on the cover, or am I being pedantic?

But Futa's daughter and literary executor Sisi'uno Langi-Helu approved of the cover, and I've come to realise that those crosses have more complex associations than my e mail admitted. As Brett pointed out, the symbol on Tupou's flag and Ellen's cover is a Greek cross. Unlike a Latin cross, which represents the crucifixion, a Greek cross has its origins in paganism and in the ideas of certain ancient Tongan thinkers. The cross's four arms of equal length can symbolise the four corners of the earth to which the Christian gospel must spread, but they have also meant, for pagan religions, Aristotle, and medieval alchemists, the elements of water, fire, earth, and air into which the universe is supposedly divided.

Futa Helu revered both the ancient Greeks and the ancient pagan culture of his own society. He gave the famous school he founded in the slums of Nuku'alofa the Tongan name for Athens, and in the essays Titus is republishing he celebrates bawdy pre-Christian songs and dances. Perhaps, then, the Greek cross, with its pagan and Aristotlean overtones, is the perfect symbol to place on the cover of Helu's book!

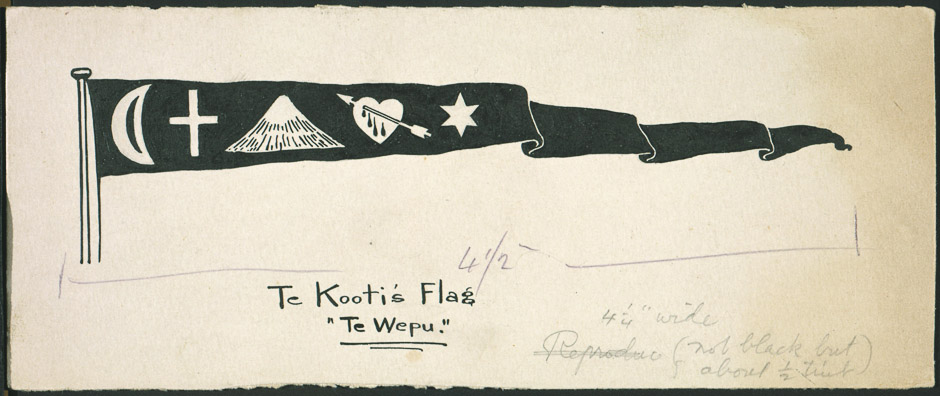

There is an intriguing connection, as well, between the Greek cross and a legendary Polynesian thinker from my part of the world. At the same time that Tupou was struggling successfully to preserve Tongan independence, a prophet, songwriter, and architect named Te Kooti was waging a guerrilla war against a New Zealand government which had unjustly imprisoned him. As he led his army through the forests and mountains of Te Ika a Maui, Te Kooti carried a series of banners adorned with symbols of the Ringatu religion he had founded. The greatest of these flags was Te Wepu, or The Whip, which was fifty feet long and got its name from the sound it made in a stiff breeze. Along with various other symbols, Te Wepu featured a Greek cross.

The Greek cross has remained one of the symbols of Te Kooti and his Ringatu faith. At Te Porere, the site of the last major battle of Te Kooti's war, a Greek cross adorns the grave where dozens of Te Kooti's followers lie together.

Te Kooti was seen by many colonial journalists and historians as a bloodthirsty anti-Pakeha maniac, but both the religion he created and the meeting houses his followers raised tell a different story. The Ringatu faith mixes traditional Maori practices with Jewish and to a lesser extent Christian theology, and the paintings which fill great Ringatu houses like Rongopai combine Maori and Pakeha imagery and techniques. In his own way, then, Te Kooti was perhaps an exponent of the the sort of fusion of Maori and European cultures and ideas which Futa Helu advocated.

[Posted by Maps/Scott]

.jpg)

7 Comments:

so WHY did Tupou I use a Greek cross on his flag? That's the mystery - and you don't answer it...

also...why did TK out it on HIS flag?

http://potolahiproductions.wordpress.com/films-on-tonga/

another interesting-looking Tongan doco:

http://spasifikmag.com/publicbusinesspage/18junwtonotbringing/

Paul has rivals!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EPMSf3jDVP0

'Atenisi foundation for rejects?

As if.

nice blog and a beautiful picture............congratulation

Post a Comment

<< Home