Neil Armstrong, and other relics of a bygone future

Television One commemorated Neil Armstrong's death by sending its reporters into the streets to ask folks how they had reacted to the news that men had walked on the moon back in 1969. There were memories of excited gatherings around blurry television sets, and of late night trips into backyards to stare up at the moon and wonder at the ingenuity of humanity.

It's a pity that the reporters didn't talk to Kiwis too young to remember the moon landings of 1969, because for the generations after the Baby Boomers Neil Armstrong and his comrades sometimes provoke different emotions.

During my 1980s childhood, the Apollo mission to the moon already seemed like something from a glorious but bygone era. Armstrong and Aldrin's joyful hours on the lunar surface, which saw them cracking jokes and playing a game of mini-golf as well as doing serious scientific work, contrasted with the endless, pointless journeys that astronauts of the eighties made into the boring stretch of space between the earth and its satellite. The dour space shuttles which navigated near space looked more like the jumbo jets of passenger airlines than the dramatic rocket which took Armstrong to the Sea of Tranquility.

The journey to the moon had been only one of scores of dramatic, history-making events of the late 1960s and early '70s. While Armstrong had been rehearsing his moon walk, millions of his countrymen had been demonstrating against racism at home and war in Vietnam, workers had been staging the largest general strike in history in Europe, and dozens of nations had been liberating themselves from colonialism in Africa and Asia. The Beatles had been reinventing music and Goddard had been reinventing film.

Many of the people who lived through the late '60s and early '70s found those years chaotic and aggravating, but by the time I was a kid events like the American Civil Rights movement and the strikes of May 1968 had become the stuff of history, and had acquired a peculiar glamour. In the World Book Encyclopedia I loved to thumb as a child, photos of Martin Luther King and handsome young Parisian rioters sat beside images of the moon landing and the Beatles in an article called The Modern World.

The sixties had been a time of relative prosperity as well as glamorous disorder. As a glum Philip Sherry broadcast the latest rise in unemployment on the six o'clock news during the dreary and austere Rogernomics era, my father loved to tell me how plentiful jobs were in the New Zealand of his childhood. Back in the sixties, he assured me, workers didn't apply for jobs - employers applied for workers. Graduates from high schools and universities had the pick of almost any career they wanted, and a job on the docks paid as well as a job in an office.

The year that Neil Armstrong walked on the moon was the year before capitalism's longest boom ended. From the forties 'til the end of the sixties, Western economies grew continuously, and unemployment fell to historic lows. In the seventies the long boom gave way to an era of stagnation, as the contradictions inherent in capitalism awoke from their long slumber. In the eighties the economic crisis saw a nasty shift to the right, as politicians like Thatcher, Reagan and our own Roger Douglas tried to restore the profitability of business by cutting state spending and letting state-subsidised industries go to the wall. In the late nineties and early noughties economies expanded again, and Thatcherites claimed that the tough policies of the eighties had created a new era of prosperity. But the financial crisis of 2008 and the Great Recession which has followed it have shown that the boom at the beginning of our century had more to do with accounting tricks than real growth.

Neil Armstrong and his era made a child of the eighties like me feel faintly melancholic, as though I'd missed out on some great adventure. For Ross Wolfe, who is a generation younger than me, the prosperity and optimism of the sixties are a torment. Wolfe is a New York graduate student, a dissident member of the Occupy Wall Street movement, and the author of a long, angry polemic called 'Memories of the Future', which excoriates the fin de siecle West for its economic stagnation, romantic anti-modernism, and low political horizons.

Like Two Dollar Stores, the Tea Party Movement, and the Jerry Springer Show, 'Memories of the Future' is a product of the exhaustion of American capitalism. As he ponders the rusting factory towns and philistine politics of contemporary America, Wolfe is haunted by earlier, headier times:

The society of the present has for several decades now been “post-futurist"...existing literally after the future historically came and went...In the absence of any viable future, the gaze of all humanity turns impotently toward the past...Hidden in the otherwise freakish sideshow of the Republican primaries this past winter, there would seem to have been a slim sliver of truth — a truth concealed in the opportunistic campaign slogans and Super PAC fundraisers of Romney and Gingrich: “Restore Our Future” and “Winning Back Our Future,” respectively. Obama’s campaign from four years ago, despite its many promises of “hope,” “progress,” and “change,” was implicitly built on comparisons to MLK, JFK, and FDR (i.e., three figures from the past). But then again, who today can be bothered to remember all the unkept promises and cynical electioneering of just four years ago?

Besides Obama and Romney, sixties leaders like Kennedy and King seem almost otherworldly. Where Kennedy's talk of technological revolution and King's speeches about social transformation seemed not only plausible but prophetic to their audiences, Obama and Romney recite words like 'hope', 'change' and 'progress' in the visionless, superstitious way that medieval peasants used to recite fragments of Latin prayer.

The moon landing of 1969 now seems so distant from us that it has acquired some of the qualities of fantasy.

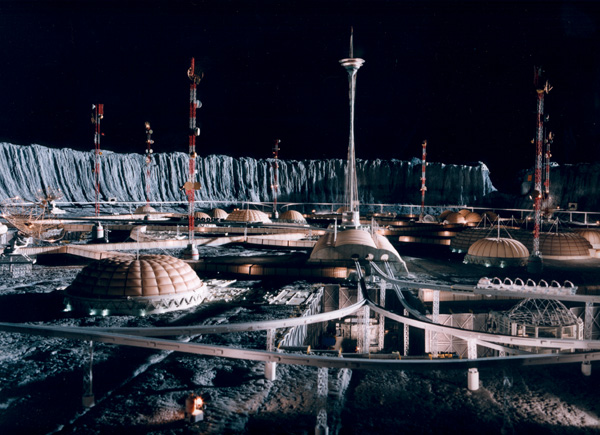

In his famous first words from the moon, Armstrong presented his adventure as another step, albeit a large one, in humanity's steady forward march. Contemporary pundits predicted that voyages to the moon would quickly become routine, and that America would establish colonies there before the end of the century. In our 'post-futurist' era, though, the journey of 1969 increasingly appears as a magical, unrepeatable event, the greatest feat of a lost civilisation.

Last year the American fantasist Jonathan Mitchell produced a radio play which imagined the adventure of 1969 ending in disaster. Mitchell's drama, which can be downloaded from the Guardian's podcast page, includes a reading of the 'contingency speech' that Richard Nixon was ready to make if Armstrong and Aldrin had not returned from their journey. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, Nixon's 'disaster' speech, with its vision of the astronauts lying dead beside their landing craft, seems less fantastic than the success of the mission to the moon.

I've also been guilty of reimagining Neil Armstrong's journey to the moon. Here's the title poem from my first book:

To The Moon, In Seven Easy Steps

1. You’re right: a small spaceship could be shot from a great gun. A hollow shell, for instance, could be fired from a nine hundred foot cannon. Unfortunately, the astronauts would be killed the second the shell was fired: they would be thrown against the floor of the shell and have every one of their bones broken. Quite apart from that, the shell itself would be destroyed by the determined resistance of the air residing in the barrel of the gun. Imagine for yourself the melancholy fate of a hollow shell hurled, at thirty five and a half times the speed of sound, against an air wall confined to a nine hundred foot tube – against a barrier quite impossible to part or push aside. We shall never get to the moon by giant artillery.

2. Nor shall we get to the moon by giant aeroplane. An aeroplane uses the sloping surfaces of its clever propellers to lever itself through the air. Around the moon, though, there is no air. Nor, let us be clear, can swans, whirlwinds, wings of eagle or vulture, or balloons lift us anywhere near that mysterious, silently moving light.

3. Perhaps the problems we face are perennial. Problems, problematic views recede from the centre of concern, only to dominate later on. Aeroplanes take off, circulate, then fall out of the sky. Moons wax and wane, pass from palm to palm. Why won’t theories stay refuted? Why won’t problems dissolve, in this upraised glass?

4. Perhaps we have never been to the moon. Perhaps we should shut windows and doors, and leave the floor undusted, and sit, silently, on the dirt, reading old newspapers in the dark. Maybe then we’ll forget that we’re at home, and be able at last to leave?

5. I have deceived you. Let us proceed to our proper business, now that the wise men have nodded themselves to sleep. It is not likely that you will ever stumble across a frozen lake, an automatic machine gun, and a light sled all at the same time, but if you do, you should amuse yourself by strapping the gun to the sled, pushing the sled on the lake, and setting the gun firing. The bullets will fly in one direction (not yours, I trust), the sled will slide in another direction, and you will know how a rocket works!

6. As you will by now have gathered, the first spaceship was simple enough: just a box with a number of rockets fastened to it. The first astronaut sat in the box, lit the rockets, and was shot away into the sky in his little carriage. The sled cuts across the lake, its stupid silver face. Now the landscape is generalised by your height. Soon it will become a map.

[Posted by Maps/Scott]

.svg/320px-Flag_of_Rotuma_(1987-1988).svg.png)

.jpg)