Studying the Pacific - and the whole world?

I had considered choosing some New Zealand intellectual as the subject for my thesis. Keith Sinclair, who shared Thompson's love of scholarship, poetry, and the rough and tumble of political life, had seemed like a lively and complex target. But I sensed that there was a chasm between what we might call the intrinsic and extrinsic significance of Sinclair's oeuvre. Sinclair's books are compulsory reading for anyone with a passion for New Zealand history and culture. He was one of the first academics to study carefully the origins of the Pakeha-Maori wars of the nineteenth century, and he also wrote an important account of the creation and maintenance of New Zealand national identity. But few scholars who are not directly engaged in the study of New Zealand read Sinclair. His investigations of our past are not often seen as relevant to the histories of other nations.

By contrast, EP Thompson's lapidarian studies of various episodes in English history, like the rise of Methodism in the nineteenth century and the depredations of poachers in Windsor forest a century earlier, have long had massive international audiences. When Thompson toured India in the mid-'70s, giving lectures on the apparently antiquarian subject of class conflict in the eighteenth century English countryside, he was treated like a pop star. By the beginning of the 1980s Thompson had become the world's most-cited living historian, despite the narrow geographic focus of books like The Making of the English Working Class and Customs in Common.

Thompson's popularity owes something to his genius, but it is also a reflection of the way that many scholars, in the southern as well as the northern hemisphere, view English history. England was the first industrial society, as well as the heartland of an empire which covered a quarter of the earth by the beginning of the twentieth century. Not surprisingly, then, England has often been viewed as the prototypical modern nation, and scholars have been keen to discover parallels between English history and stages in the development of their own countries. Thompson himself was well aware of the way in which his work could be read. In his preface to The Making of the English Working Class he suggested that, because 'the greater part of the world today is still undergoing problems of industrialisation' his book might seem directly relevant in 'Asia or Africa'. Thompson told stories which had extrinsic as well as intrinsic significance. He could write about England and the world at one and the same time.

The Pacific has often been regarded as a peripheral part of the world. Most of the region's central and eastern islands remained unpopulated until several thousand years ago, and some of them, like New Zealand, have human histories not much longer than a thousand years. When Europeans reached the Pacific in force a couple of hundred years ago, they saw it as a place without history. For missionaries like Augustus Selwyn and artists like Gauguin, Pacific Islanders were people who lived in a perpetual present, innocent of the chronologies and innovations which were part of human life in more northerly latitudes. Some Europeans, like the syphilitic Gauguin, saw Islanders as noble savages pursuing lives of guiltless hedonism in southern Edens; others, like the appalling Selwyn, talked darkly of heathenism and cannibalism, and presented the Pacific as a place of dangerous ignorance rather than blessed innocence. Whether they were seen as noble or ignoble savages, though, the people of the Pacific were contrasted with their counterparts in the northern hemisphere. The Pacific was the antithesis of Europe.

Even today many inhabitants of the north find the nineteenth century view of the Pacific compelling. Paul Theroux's The Happy Isles of Oceania, which accuses Pacific peoples like the Samoans and Tongans of a willful, comical ignorance about the outside world, is the most popular contemporary study of our region.

Since the late nineteenth century most New Zealanders have been white, but this country has nevertheless often been viewed through nineteenth century cliches about the Pacific. In the early 1930s and '40s, 'literary nationalists' like Charles Brasch, Monte Holcroft, and the young Allen Curnow bemoaned their homeland's supposed lack of anything resembling a history. This 'far-pitched perilous place' was the antithesis of ancient, sophisticated Europe. In recent decades a set of images summed up in the phrase 'New Zealand Gothic' has infected film, television and media portrayals of rural regions of our nation. Gothic New Zealand is a place of dark, continually raining skies, brooding rot-green hills, and homicidally paranoiac farmers born of incestuous unions. In the northern hemisphere imagination, the Gothic Kiwi is the white equivalent of the Fijian cannibal or the Tahitian nymphomaniac.

Serious scholars of the Pacific have long since shucked off cliched representations of the region. In the early decades of the twentieth century, scholars like Bronislaw Malinowski, Raymond Firth and Te Rangi Hiroa revealed the social complexity and intellectual vitality which even small Pacific societies like Tikopia, Mangaia and the Trobriands possess. Since World War Two historians, anthropologists, sociologists, ethnomusicologists and art historians have produced a vast and sophisticated literature on the Pacific.

Yet the Pacific, with its small nations and isolation from centres of power, has remained an economically and politically marginal part of the globe. The obscurity of the Pacific has allowed the perpetuation of old stereotypes in the popular imagination of the north, and has also dissuaded many northern scholars from studying and thinking about the region. Where EP Thompson benefited from the centrality of his society to world history, Pacific scholars suffer from the marginality of the homelands they study.

Shortly after I'd finished my PhD I discovered the work of the Hawa'iian-born anthropologist Patrick Vinton Kirch. As soon as I'd read the introduction to Kirch's magisterial 1986 book The Evolution of the Polynesian Chiefdoms, I realised that he had found a way to overcome the marginalisation of Pacific history. Kirch acknowledges that the Pacific is a relatively isolated region which has played only a small role in world affairs, but argues that these facts make the region more rather than less worthy of study. Kirch believes that we can treat the Pacific as a sort of laboratory, where conflicting theories about the pattern and meaning of human history can be tested.

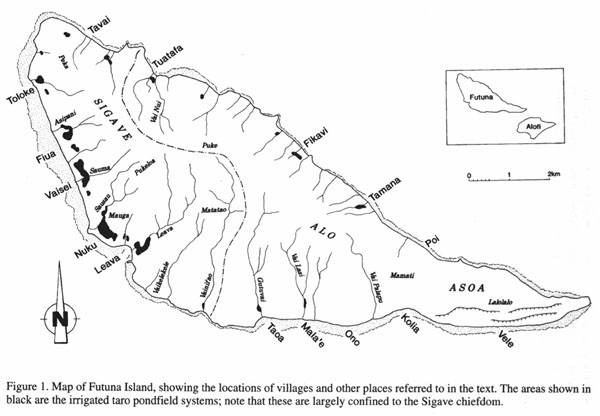

Kirch's 1995 book The Wet and the Dry finds him at work in his laboratory. Deciding to test Karl Wittfogel's 'hydraulic hypothesis', which holds that societies dependent on irrigation tend to be hierarchical and statist, Kirch considers the West Polynesian island of Futuna, which was traditionally divided into an extensively irrigated 'wet' region called Sigave and a 'dry' area called Alo, where irrigation is much more difficult. Kirch notes that, contrary to what Wittfogel's theory might lead us to believe, Alo has traditionally been a much more hierarchical, centralised, and martial society than Sigave. Kirch turns to other Polynesian societies like Hawa'ii, and argues that they also contradict the 'hydraulic hypothesis'.

Wittfogel's ideas, which derive partly from Marx's very problematic notion of an 'Asiatic mode of production', had a considerable influence on the study of Eastern societies in the twentieth century. Testing Wittfogel in the laboratory of the Pacific, though, Kirch finds him wanting. I'd like to think that The Wet and the Dry has contributed to the decline of Wittofgel's reputation in the twenty-first century.

Patrick Vinton Kirch's research interests are very different from mine. He is an authority on the pre-European history of the Pacific, whereas I have tended to study the ideas and culture of modern palangi societies like Britain and settler New Zealand. But it seems to me that Kirch's notion of the Pacific as a laboratory might be adapted and used by scholars of modernity.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, both indigenous and palangi inhabitants of the Pacific imported not only technologies and consumer goods but ideas from wealthy, populous nations of the northern hemisphere. In the Pacific, modernist ideas from the northern hemisphere were transmogrified, as they were reinterpreted to meet local conditions and augmented and amended with locally produced concepts. Because the Pacific has been relatively isolated from other regions, even in the modern era, imported ideas have sometimes developed in peculiar ways here.

By studying the careers of some important modern ideologies in the laboratory of the Pacific, we can view familiar concepts and arguments from new and strange angles. That, at least, is the idea behind a a research project I've been trying to plan this week. I want to pursue the project next year, when I'll be spending some quality time in Tonga.

THINKING UPSIDE DOWN: EXAMINING MODERNITY AND IDEOLOGY IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC

Like Europe, only different: Tupou I and the making of modern Tonga

In the middle decades of the nineteenth century, a chief named Taufa'ahau waged a long series of military and political campaigns to unite his country and make himself Tupou I, the first king of modern Tonga. With the help of anti-imperialist Britons and Americans, Tupou I proclaimed the emancipation of Tonga's peasants, turned his country's chiefs into civil servants, established a parliament, and created an unusual economic system that prevented the alienation of Tongan land.

Tupou I's reforms were inspired partly by the bourgeois revolutions which transformed Europe in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and they helped Tonga maintain its independence from a host of would-be colonisers. Scholars disagree, though, about the extent and meaning of Tupou's achievements. Was he a democrat or a tyrant? What does his rule of Tonga tell us about the content of the bourgeois democratic ideas he imported from Europe?

Ruthlessly improving the natives: hypermodernist ideology and New Zealand rule in Samoa

Many thinkers in early twentieth century Pakeha New Zealand society venerated industry and science. Groups on the left as well as the right of the political spectrum embraced utopian visions of scientifically-guided economic and social progress. HG Wells' scientific utopias were enormously popular, and were imitated by homegrown writers like John Macmillan Brown. The new 'science' of eugenics excited many Kiwis.

Hypermodernist ideology was never a strong influence on a New Zealand government, but for more than a decade it guided Kiwi administrators in the colony of Samoa, which had been taken from Germany during World War One. Determined to turn Samoa into a modern capitalist country and consign traditional Polynesian culture to museums, New Zealand administrators tried to break up collectively owned blocks of land and replace the ancient villages of 'Upolu and Sava'ii with new, 'rational' settlements laid out in grid-like patterns. New Zealand's attempt to transform Samoa led to opposition, bloodshed, and failure. What does this ill-fated experiment tell us about the hypermodernist thinking which was so pervasive in the West during the first decades of the twentieth century?

Mixed blood and foreign soil: the strange story of Samoa's Nazis

The Samoan Nazi Party was formed in 1934 by a German settler with a Tongan wife, and its members and supporters included many afakasi. The party, which called for Germany to reclaim its Samoan colony from an unpopular New Zealand administration, hung portraits of Adolf Hitler on the walls of its headquarters on Apia's waterfront, and established a paramilitary wing which trained secretly in the countryside.

The Samoan Nazis were recognised by Hitler's regime, and even sent two representatives to a world congress of fascists held in Hamburg in 1937, but their unusual understanding of racial purity ensured that they were frequently engaged in fraught discussions with their German allies, who refused to consider Polynesians members of the Aryan race. After the outbreak of World War Two many members of the Samoan Nazi Party were interned on Wellington's Somes Island, and the organisation never reestablished itself. Samoa's Nazis offer us some fascinating insights into the contradictions and limitations of fascist ideology.

A 'communist state' in rural Fiji: the Bula Tale movement

At the beginning of the 1960s four villages in the western backblocks of Viti Levu announced their intention of seceding from Fiji. Led by Apimeleki Ramatau Mataki, a former junior civil servant, the Bula Tale movement rejected the authority of both the British colonial administration in Suva and traditional Fijian culture. Members of the movement refused to recognise colonial laws, eschewed kava drinking and other traditional cultural practices, collectivised many of their possessions, and abolished money. Ramatau said that he wanted to create a 'communist state' in the villages where he had influence, and his movement was sometimes known as the Bula Tale Communist Party.

At its high point in 1961, the Bula Tale movement had one thousand members and support in many parts of Fiji, and was being denounced by both colonial administrators and high chiefs. What place should the Bula Tale movement have in the history of the diffusion of radical left-wing ideas? What does the movement tell us about the relationship between communist ideology and Fijian tradition?

Blood in the kava bowl: Epeli Hau'ofa's confrontation with Marxism

In the years before Sitiveni Rabuka's coups in 1987 the Suva campus of the University of the South Pacific was an exciting place, where scholars from around the world taught and argued. One of university's stars was Epeli Hau'ofa, a short story writer, novelist, poet, and anthropologist who had grown up in Papua New Guinea, where his Tongan parents had been missionaries. Hau'ofa is best-known today for his 1990s essays 'Our Sea of Islands' and 'The Ocean in Us', which changed the direction of Pacific studies by insisting that peoples like the Tongans and Fijians should be considered not as isolated denizens of small societies but as the frequently mobile citizens of a single vast region.

During the late 1970s and '80s Hau'ofa often wrestled with the Marxist ideas which a series of palangi academics promoted at the University of the South Pacific. Like a number of other important Pacific thinkers, Hau'ofa was both attracted and repulsed by the materialism and universalism of the Marxism he encountered in Suva. In his great poem 'Blood in the Kava Bowl' Hau'ofa dramatised a debate with Michael Howard, an American scholar who taught at Suva until 1987 and in 1991 published a Marxist history of Fiji. What can we learn from Hau'ofa's confrontation with Marxist ideas?

To Import the Enlightenment: Futa Helu, 'Atenisi, and Tonga's pro-democracy movement

In the early 1960s Futa Helu, a young Tongan who had studied at Sydney University with the philosopher and satirist John Anderson, founded a private school in a swamp near the western edge of Nuku'alofa, and called it 'Atenisi, the Tongan word for Athens. Helu's school would become a bridge over which much of the Western tradition in philosophy, literature, and music would reach Tonga. Like his hero Socrates, Helu was unafraid to speak truth to power, and in the 1980s and '90s his school became the headquarters of Tonga's pro-democracy movement. The historian Ian Campbell has argued that, by training thousands of young Tongans in critical thinking, 'Atenisi had a 'devastating' effect on notions of the divine right of kings and the union of church and state promoted by the twentieth century Tongan elite.

Up until his death in 2010 Helu insisted on the universality of reason and science, and condemned both moderate and radical forms of cultural relativism. He repeatedly argued that Tongan culture lacked a critical spirit, and needed an infusion of Greek and Enlightenment ideas. Although Helu was passionate about Tongan poetry and dance as well as Greek philosophy and Italian opera, he has been accused of Eurocentrism by some of his fellow Tongan intellectuals. What can we learn from Futa Helu's attempt to import the Enlightenment into Tonga?

Giving time an end: Tonga's Tokaikolo Fellowship and the 'coup' of 1990

In 1978 a group of ministers split from Tonga's dominant Free Wesleyan Church and established their country's first pentecostal sect. The Tokaikolo Fellowship preaches the importance of subjective religious experience, and at its gatherings worshippers often talk in tongues, move wildly, and utter prophecy. In the 1980s the Fellowship aligned itself with Tonga's nascent pro-democracy movement, and against the country's political and religious establishment.

In April 1990, the Fellowship baffled its liberal friends by hosting two pentecostal preachers from New Zealand who warned that Satanists and communists were preparing to stage a military coup in Tonga. Acting on the advice of the Kiwis, the Fellowship turned its churches on the island of Tongatapu into armed compounds and prepared to wage a campaign of resistance against the coming coup. The Fellowship's actions caused general panic, and forced the Tongan government to issue a statement rubbishing claims about a coup. Arguably, the Tokaikolo Fellowship's strange behaviour in 1990 tells us a great deal about the contradictions between traditional Tongan and modern Western notions of time and history.

All that should help keep me out of mischief next year...

[Posted by Maps/Scott]