[It's exam time at 'Atenisi, so I've prepared this summary of my rather chaotic Modern Pacific History paper for students. I'll post about the visit from Murray Edmond last week as soon as I can track down the photographs I took of his ebullient public performances.]

Modern Pacific History – a summary

What’s in a name?

In our first

lecture I argued that names like the Pacific are much more than simple and

permanent labels placed on pieces of the world. A name reflects the outlook and

interests of the person or people who created it, and over centuries and

millennia many different names have been given to the region we today call the

Pacific.

In a number

of ancient Polynesian cultures, ‘Moana’ was used as a name for the waters we

now call the Pacific. In the sixteenth century Spaniards journeyed from Cape

Horn at the bottom of South America to Southeast Asia, and gave the name

Pacific, which meant peaceful, to the great ocean they had crossed. The

Spaniards may have picked a different name if they had run into a cyclone, or

had called at an island like Tongatapu, whose inhabitants were very familiar

with the martial arts.

Nineteenth

century palangi writers like Robert Louis Stevenson made the South Seas into a

popular and rather romantic term for the southern and central Pacific. In the

decades after World War Two the term South Pacific began to be used by

international bodies like the United Nations. Today politicians like New

Zealand’s John Key often talk about an Asia-Pacific region, and by doing so

lump small island societies like Tonga together with much more populous

continental nations like South Korea and Thailand.

The great

Tongan-born intellectual Epeli Hau’ofa used an essay called ‘Our Sea of

Islands’ to argue that European colonists had thought of the Pacific Ocean as a

barrier between island peoples, when it really been, in precolonial times, a

highway. Hau’ofa disliked the term Pacific because it made him think of barren

water, and proposed using the word Oceania instead. More recently, the ‘Atenisi

graduate ‘Okusitino Mahina has proposed once again using the ancient and

beautiful word Moana to describe the waters around the nations of Tonga, Samoa,

and Fiji.

I asked

class members to think about which word or words they would like to use to

describe the region where they live. Ilaisa said that he believed that a

pan-Pacific identity existed, but did not identify with the term Asia-Pacific.

Salise argued that the Pacific should be renamed Moana-a-Tonga, to remember the

empire that Tonga’s mariners and warriors established in the late medieval era.

I also used

our first lecture to explain the structure, or rather lack of structure, of the

paper. I explained that our class would imitate the great Doctor Who’s Tardis,

and jump from one time and place to another in lecture after lecture. Where the

Doctor explored the whole universe, we would confine ourselves to the Pacific

since the late eighteenth century.

A blind date

I argued

that the first encounters between Europeans and Pacific peoples could be

compared to a blind date, because each people lacked information about the

other, and in place of information relied on preconceptions. These preconceptions

were very different, and reflected the different historical experiences of

European and Pacific peoples.

To

understand the preconceptions that European and Pacific peoples brought to

their first meetings, we had to examine the different histories of these

societies.

The European background

We looked

first at Europe, which was experiencing rapid and fateful changes when mariners

like Bougainville and Cook set sail for the Pacific. The intellectual movement

we now call the Enlightenment was challenging the power of religion, by

insisting that the world must be understood through observation and reason,

rather than on the basis of theological dogma.

The economic

system we now call capitalism was emerging in Europe, as agriculture became

increasingly large-scale and profit-oriented, peasants were cleared off their

lands, towns began to grow, and gold and other commodities flowed in from

colonies in other continents. Many scholars have used the term modernity for

the world that the Enlightenment and capitalism brought into existence.

I argued

that early European responses to the Pacific were dictated largely by

preconceptions, rather than by reality. The Pacific was, for Europeans, a

mirror in which they saw aspects of their own troubled societies. Many Europeans

unhappy with the greed, hierarchy, snobbery, sexual repression, and poverty of

their society saw, in early descriptions of Tahiti, the island Bougainville

‘discovered’ in 1767, an alternative and better way of life. Influenced in many

cases by the social critic Rousseau, who praised the life of the ‘natural man’ living

outside European society, these Europeans saw the Tahitians as a people who existed

close to the soil, abhorred authority and violence, and saw sex as something

sacred rather than abominable. The Tahitians were, to use a famous phrase

coined by the English poet John Dryden, ‘noble savages’.

But not all

Europeans were enthusiastic about the Pacific. The same apparent sexual and

social freedom which appealed to devotees of Rousseau upset defenders of

Christianity and European imperialism. For Europeans who believed that

Christianity and commerce were gifts that had to be shared,

societies like Tahiti and Tonga were the ‘dark places of the earth’, where

sloth and hedonism reigned. The inhabitants of these dark places were not noble

but ignoble savages. In 1796 a ship called the Duff left England for Tahiti and Tonga, full of missionaries

determined to Europeanise the peoples of those lands.

I noted Kerry

Howe’s argument that certain common assumptions lie behind both the stereotype

of the noble savage and the stereotype of the ignoble savage. Both the noble

and ignoble savage are supposed to be the product of a timeless, static

society; both are supposed to be incompatible with a modern, European-made

world. Howe notes that, for much of the nineteenth century and the early

decades of the twentieth century, many Europeans assumed that the inhabitants

of the Pacific would die out, as a result of contact with Christianity, commerce,

and colonisation.

Neither the

noble nor the ignoble savage ever existed. Tahiti, Tonga and other Pacific

societies were far more complex than either stereotype suggested.

The Pacific Background

The Pacific

is an extremely diverse part of the world, and different societies brought

different preconceptions to their early encounters with Europeans. To

illustrate something of the Pacific’s diversity, I discussed the chart Patrick

Vinton Kirch designed to show how hierarchical various

Polynesian societies were in the centuries before contact with Europe.

At one end

of Kirch’s chart is Rekohu, the society that the Moriori people established in

the subantarctic Chatham Islands. The Moriori, who were the descendants of

fourteenth century Maori mariners, survived by hunting and gathering and had an

egalitarian, decentralised society. At the other end of Kirch’s chart is Tonga,

a highly centralised agricultural society where a class of serfs were separated

by wealth and culture from a leisured aristocracy. Tonga had developed

rudimentary state structures and an empire by the late medieval period.

It is not

surprising that the people of Rekohu and Tonga reacted differently to European incursions

on their rohe. When a European vessel landed on Chatham Island in 1791, the

Moriori were startled. Because they had imagined that they were the only people

in the world, they decided that the ship and its crew must have come from the

sun. By contrast, the chiefs of Tongatapu were relatively indifferent to Cook

when he first called here. Shortly after landing Cook had associated himself

with a low-ranking chief, and this suggested, to more senior leaders, that he

must be a visitor of little importance.

Ungodly trouble

I devoted a

lecture to a couple of the early attempts to turn Polynesians from ignoble

savages into industrious Christians. Using an essay by Paul Van Der Grijp, I

discussed the fate of the first missionaries to land in Tonga, who were brought

by the Duff in 1797. Because of their

refusal to study Tongan society with any seriousness and the arrogance they

showed towards both Tongans and the small but influential number of rough and

ready palangi ‘beachcombers’ who had already settled in Tonga, the missionaries

became the victims of both theft and violent attacks, and eventually fled from

the nation they had hoped to convert. A missionary named George Vason ‘went

native’, married a series of local women, took part in a civil war, acquired

serfs, and had his body tattooed.

Vason’s

rejection of European for Tongan civilisation foreshadowed the story of Thomas

Kendall, an English missionary who became, in the second decade of the

nineteenth century, a lackey of the notorious Maori warlord Hongi Hika. Kendall

had intended to convert Hika, but ended up supplying him directly and

indirectly with the guns that would help him ravage much of Te Ika a Maui. The

fates of Vason and Kendall were not unusual in the early nineteenth century.

A digression and a debate: North

Sentinel Island

A handful of

‘uncontacted peoples’ unfamiliar with the world of modernity still exist

today. I suggested to the class that we could understand the situation of the

Moriori people in 1791 by considering the plight of the uncontacted people of

North Sentinel Island.

I described

how the inhabitants of North Sentinel, which is part of the Andamans

archipelago in the Bay of Bengal, had resisted repeated attempted incursions by the British colonisers of the Andamans and then by the Indian

government. Boats and choppers that got too near North Sentinel Island attracted

swarms of arrows. Today the Indian government refrains from trying to contact

the North Sentinelese, and bars private vessels from going near their island.

Class members disagreed vehemently over whether the North Sentinelese ought to

be visited again by emissaries of the modern world. At one extreme, Ilaisa

argued that the islanders should subdued by force and introduced to the Bible;

at the other extreme, Miko argued for their indefinite isolation, suggesting

they were better off apart from the modern world.

Two-sidedness and countermodernity

Shortly

after World War Two the Australian scholar Alan Moorehead published a book

called The Fatal Impact, which became

famous for its argument that the peoples of the Pacific had been devastated and

doomed by the impact of contact with European missionaries, capitalists, and

colonists. Moorehead’s book was popular because it reflected a common palangi

view, but in the 1960s a group of scholars based at the Australian National

University began to develop a new ‘island-centred’ vision of Pacific history,

in which Pacific peoples were not passive victims of history, but instead

adapted creatively to the changes Europeans brought to their societies in the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The ANU

scholars’ picture of Pacific history as a two-sided process has become dominant

in the academy, but Moorehead’s viewpoint still has its advocates. In New

Zealand the charismatic Maori politician Hone Harawira often argues that Maori

lived in a peaceful paradise before being losing their power and agency to

European invaders. The Tongan academic Linita Manu’atu sees her country as a

victim of cultural colonisation, and wants to restore its pre-contact culture.

I argued

against the ‘fatal impact’ view of Pacific history, and suggested that it had

echoes of the old notion of a noble savage doomed to destruction if his

timeless paradise is disturbed by outsiders. I invited class members to

consider the earlier contacts between Europeans and Pacific Islanders, and the

stories of men like George Vason and Thomas Kendall, and decide for themselves

whether Pacific cultures were as brittle as Moorehead and Manu’atu believe.

I argued

that, rather than succumb tamely to the palangi newcomers, Pacific peoples

constructed a series of ‘countermodernities’ during the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries, by appropriating and adapting the modern ideas,

institutions, and economic practices that had emerged in Europe during the

eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. These countermodernities soon came

into conflict with European missionaries and colonists.

Countermodernity and resistance: Aotearoa,

Samoa, and Tonga

I used a

series of lectures to discuss the countermodern societies that various

Polynesian peoples constructed, and the ways that these societies came into

conflict with European imperialists.

I described

the life and work of Wiremu Tamihana, the Waikato chief who created the

Kingitanga, or King movement, in an attempt to unite Maori against European

settlers in the middle of the nineteenth century. I discussed the village

called Peria which Tamihana established as a model for the Maori assimilation

of European technology, ideas, and forms of organisation. Peria had a flour

mill which was owned and operated collectively, a school which taught lessons

in Maori, and a church which offered a version of Christianity that reflected

Maori experiences. The Waikato Kingdom which grew around Tamihana in the 1850s

and early ‘60s was a prosperous and independent nation which exported huge

amounts of food to the impoverished colonial city of Auckland. It was invaded

and conquered by colonists in 1863 and 1864.

We used

another lecture to examine the life and work of Rua Kenana, a Maori prophet who

tried to establish an independent state in the Urewera mountains of central Te

Ika a Maui. I described Rua’s courage in facing up to persecution from the

settler government of New Zealand, but also noted his claims to divine status,

and his use of this claimed status to intimidate or deceive his followers. We

watched some of Vincent Ward’s feature-length documentary film Rain of the Children, which shows the

terrible poverty of Maori who had been robbed of their land by settlers, and

the desperation which led them to Rua’s movement. When we discussed Rua

Kenana’s place in history, several class members argued against judging him too

harshly. Tevita argued that Rua “was a man who did what he had to do in his

time.”

We used the

work of the distinguished Samoan writer Albert Wendt as a route into the history of

Samoa’s anti-colonial Mau movement, which brought New Zealand rule of the

island of Upolu to a standstill in the late 1920s and early ‘30s with

roadblocks and tax boycotts. The Mau established its own government in a

village on the edge of Apia, and proclaimed the slogan Samoa mo Samoa (Samoa

for the Samoans).

At the end

of 1929 New Zealand police opened fire on a Mau protest march, and the movement’s

leader was killed. This bloody act was followed by a de facto counterinsurgency

campaign, during which Kiwi troops and police pursued Mau activists through the

jungles of Upolu, and burned pro-Mau villages to the ground. Wendt’s parents

were involved in the Mau, and some of his writings deal with the movement. We

watched Shirley Horrocks’ documentary A

New Oceania, which discusses Wendt’s life and work, and shows images from

the Mau era.

I argued

that Tonga’s first modern king, Tupou I, created a countermodern society in

Tonga, by creating a modern state, complete with a constitution and a set of

ministries, and abolishing the quasi-feudal system which had existed in his

country for centuries, but at the same time turning down the demands of palangi

capitalists for the opening of Tonga to foreign ownership. Tupou was successful

in preserving Tonga from colonisation, and I argued that he succeeded partly

because Tonga, unlike Aotearoa or Samoa, had a long tradition of centralised

government and a national identity.

Modernity and confusion: cargo cults

considered

We devoted a

lesson to cargo cults, which I defined as movements that aim to give their

members material rewards associated with modernity through the use of magical

rituals.

We discussed

the most famous of all cargo cults, the John Frum movement from Tanna Island in

Vanuatu, whose members believe that certain rituals – the raising of an

American flag, for instance – will encourage an American soldier who served on

Tanna during World War Two to return with a vast ‘cargo’ of modern goods and

cash. We also considered a much more obscure cult which existed on Atiu Island

in the Cooks shortly after World War Two, where a group of followers of

a self-proclaimed prophetess cleared forest so that a ‘ghost ship’ could

arrive carrying goods.

After giving

a quick account of some of the main trends in the plentiful scholarly

literature on cargo cults, I asked class members to consider how they felt

about the phenomenon. One class member dismissed cargo cultists as fools.

Tevita argued that cargo cults could be construed as countermodernities; I

disagreed with this, because I think that cult leaders lacked the sort of understanding

of how to appropriate and manipulate modernity that leaders like Wiremu

Tamihana and Tupou I clearly showed.

Antimodernity: the case of the Kwaio

For a

century and a half, the Kwaio people of Malaita in the Solomon Islands have

resisted modernity in almost all its forms. Today the Kwaio continue to live in

semi-nomadic groups, shun most modern goods, and practice their traditional

religion. Kwaio have forged a reputation as ferocious defenders of their

autonomy. In the nineteenth century they frequently attacked the European boats

which came to Malaita in search of sandalwood and slave labour, and in the

1920s they killed many of the members of a party of tax collectors sent by the

British administration of the Solomon Islands.

The Kwaio

were an important part of the Maasina Rule movement which challenged British

control of the Solomons in the years after World War Two, and more recently

they have been opponents of the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon

Islands, an Australian-led intervention in the Solomons. I talked about the

work of the Marxist anthropologist Roger Keesing, who wrote extensively about

the struggle of the Kwaio to preserve their traditional way of life. Keesing

became so influential amongst the Kwaio that the Solomon Islands government

banned him from visiting Malaita, on the grounds that he was stirring up

protest there.

I asked

class members to consider their attitudes to the Kwaio. Salise argued that the

Kwaio ought to be allowed to live autonomously from the Solomon Islands state,

though he considered their hostility to modernity “a little extreme”.

A field trip to ‘Eua

Four days on

the verdant and rugged island of ‘Eua gave us a chance to put some of the ideas

we had been discussing in the classroom into practice. During our time on ‘Eua

we talked with Richard Lauaki, a member of Tonga’s Niuan minority and an

authority on the history of both Niuafo’ou and his adopted home. Richard’s two

hour talk, which mixed historical insights with improbable claims, and included

talk of divine intervention in human affairs, helped us to think about the

problems that scholars like Roger Keesing must have faced when they collected

oral history. We read

Sione Latukefu’s essay ‘Oral Tradition and Tonga’ to help us with these

problems.

We encountered more problems when we tramped to the highest point on

‘Eua, following a trail used by Cook, and found the grave of the New Zealand

soldier Shorty Yealands there. ‘Euans told us five different stories about how

Yealands died; each of these stories contradicted the official version of his

death.

When we

returned from ‘Eua we looked at Tonga's experiences in World War Two.

Drawing on essays by George Weeks and Elizabeth Wood-Ellem, I described the

influx of Americans and New Zealanders to Tonga, and the clashes which broke

out due to the brutal racism of some Americans and the Tongan habit of

‘borrowing’ goods like tobacco and torches from American warehouses. The

lecture was an attempt to put into context the killing of Shorty Yealands by a

Tongan soldier placed on a demoralising punishment drill for theft. I argued

that the Second World War marked the first great challenge to the system Tupou

I had established in the nineteenth century. Tupou I and later Queen Salote had

wanted to limit the influence of capitalism on Tonga, but the presence of

twenty thousand free-spending Americans lured many Tongans off their plantations

and into the cash economy.

Papua New Guinea: a primitive

exception, or a glimpse of the future?

We began our

lesson on Papua New Guinea by examining a magazine article on the recent killings

of women suspected of sorcery in the country’s highlands. The killings, which

have prompted international condemnation and anguished debates in Papua New

Guinea’s parliament, have been seen by some observers as confirmation of the

inherent violence and backwardness of New Guinean society. Class members seemed

to share this dim view of New Guinea. I argued that they were succumbing to the

old stereotype of the ignoble savage, and suggested that sorcery killings might

in some ways be an expression of the failings of capitalism in Papua New Guinea.

Drawing on

an essay by Michael A Rynkiewich, I discussed the ‘big man’ system which

emerged in ancient New Guinea. Because they lacked central authority, the

fragmented societies of New Guinea relied on ‘big men’, who had proved

themselves by oratory or bravery in warfare, to knit them together temporarily.

The big man specialised in attracting prestige and resources to his corner of

New Guinea.

The big men

were co-opted by the Australian colonisers of New Guinea, and after

independence in 1975 they became MPs and local government officials, intent on

winning state resources for their part of the country. These political big men

lack any ideological vision or national consciousness, and are prepared to see

one region deprived of funding so that they can reward their followers. They

pillage the state and jump from one party and coalition to another in search of

short-term advantage.

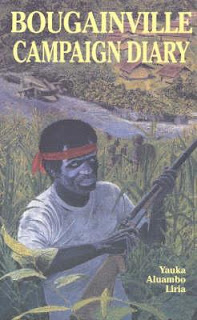

Citing the

remarkable journal published by a senior Papuan military intelligence officer, I

described how big man politics saw Papua New Guinea lose its war against the

secessionist province of Bougainville, despite a massive advantage in troops

and materiel. I suggested that today big man politics makes a reasoned response

to the sorcery killings difficult. I argued that the sorcery killings might be

compared to the Rwandan genocide of 1994, in the sense that they are motivated

more by impoverished people’s desire to steal land from their victims than by

some primordial savagery. I suggested that, with its huge population and

mineral-rich economy, Papua New Guinea would be crucial to the future of the

Pacific, and thus needed careful study.

Andy Leleisi’uao and Pacific identity

We finished

the course by returning to the question of Pacific identity. I described the

career of Andy Leleisi’uao, an artist born in the Auckland suburb of Mangere to

Samoan parents.

Leleisi’uao

is a self-taught artist, and many of his early paintings dealt with

controversial issues in Samoan society. He condemned the influence of greedy churches

on Samoans, and lamented the effects of alcohol on Samoan men. In his later

works Leleisi’uao has constructed an elaborate fantasy world, where UFOs sit on

tropical Polynesian islands and hybrid creatures wander landscapes covered in

glowing ruins.

Several

years ago Leleisi’uao became involved in a dispute with some members

of Mangere’s Pacific community, after he had painted a mural full of strange

horned creatures for the Mangere community centre. Conservative Pacific

Islanders, including influential religious leaders, campaigned successfully

against the mural. Leleisi’uao was infuriated by their claims that he had lost

touch with his culture.

Perhaps

partly in response to criticism of his work from within the Samoan community,

Leleisi’uao created a manifesto in which he defines himself as Kamoan – the

word is a mixture of ‘Kiwi’ and ‘Samoan’ - and invited anyone to share this new

identity. We discussed Leleisi’uao’s dispute with the Mangere community, and

his bold attempt to create a new identity for himself. Class members were

strongly supportive of Leleisi’uao in his struggle with the Mangere community,

feeling that nobody should be allowed to make a definitive judgment about what

is and isn’t part of a Pacific culture.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]