Chris Finlayson's battle with language

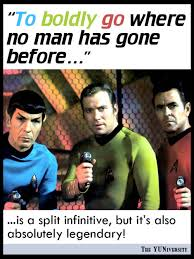

Attorney General and Minister of Treaty Negotiations Chris Finlayson has sent his staff a set of rules to follow when they write his speeches, press releases, and letters to constituents. The directive bans Finlayson's employees from using a slew of words, and warns against the evils of split infinitives and Oxford commas.

With its trenchant tone and interest in the minutiae of language, Finlayson's guide to the English language might seem reminiscent of HW Fowler's famous Modern English Usage, which was first published in 1906, at a time when mass literacy was still a work in progress in the West.

Fowler is nowadays often considered a fusty pedant, but his book was, and perhaps remains, an innovative, polemical document. Like Ezra Pound and other the modernist poets who would soon found the Imagist movement, Fowler broke with the late nineteenth century fashion for verbal luxuriance by advocating clarity and concision. Instead of the elaborate word-paintings of sunsets and moonlit nights favoured by late Victorian versifiers like Swinburne, Pound demanded precise and suggestive imagery; with the same briskness, Fowler urged journalists and politicians to speak concretely rather than in what he called ‘abstractese’.

Far from being a pedant, Fowler refused to turn his arguments about language into rules. Modern English Usage contains a long and famous passage on split infinitives that offered some sensible advice:

We maintain, however, that a real split infinitive, though not desirable in itself, is preferable to either of two things, to real ambiguity, and to patent artificiality…We will split infinitives sooner than be ambiguous or artificial; more than that, we will freely admit that sufficient recasting will get rid of any split infinitive without involving either of those faults, and yet reserve to ourselves the right of deciding in each case whether recasting is worthwhile.

Fowler knew language was a vast and unstable element. To try to control it with a set of general rules would be like trying to fence an ocean.

There is an interesting contrast between HW Fowler’s aversion to dogma and Chris Finlayson’s attempts to make hard and fast rules for his staff. Finlayson’s dogmatism reflects an attitude toward language that has become ubiquitous in contemporary Western societies.

In an interview with Radio New Zealand, the Attorney General explained that he considers it a duty to communicate as ‘clearly’ as he can with his constituents. Language works best, he suggested, when it is at its clearest. Finlayson conceives of language as a sort of essentially neutral communication device, like a cellphone or e mail account, through which information can be delivered from one individual to another. He has a thought, and the thought is transmitted to a constituent in a letter or speech or press release. The clearer the language he uses, the greater the chance that his thought will be apprehended.

Finlayson’s attitude to language can be related to his politics. As an admirer and advocate of free market capitalism, he considers human society nothing more than the sum total of the actions of an aggregate of free and rational individuals. Just as these free and rational individuals are wholly responsible for their beliefs and choices, so they are entirely responsible for the meanings of the language they use. If there is any ambiguity in a piece of language, then this is the result of some individual’s failure to stop splitting infinitives, or breaking some other rule.

What Finlayson and his co-thinkers on the right miss is the irreducibly social and historical nature of language. A word, like other living thing, is the product of a long and intricate history, and remains susceptible to evolution. Because the words we speak and write were used before us by other men and women, and continue to be used in a variety of contexts, we can never control all of their meanings. When we are confronted with some of the various meanings a word can have, we are called upon to make a choice about which meanings we want to use, and which we want to ignore. These choices are unavoidably ideological.

It is interesting to consider the history and meanings of one of the words that Chris Finlayson has forbidden his employees from using. ‘Community’ has Latin and French ancestors, but it had entered the English language by the late Middle Ages, when it was sometimes spelt commonty, and when it could refer to an economic, regional, or religious organisation – to a trade guild or a village or a cluster of monks. In the aftermath of England’s revolution, ‘community’ seems to have acquired, on some tongues at least, a class consciousness: it could stand for the ‘common people’, and implicitly contrast them with the aristocrats who still dominated institutions like parliament. The men and women who built England’s trade union movement in the nineteenth century often used the word in their orations and writings.

By the twentieth century, at least, cultural conservatives were using the word 'community' to describe a traditional society they believed was menaced by sinister forces. The famously grumpy literary scholar FR Leavis lamented the passing of the ‘organic community’ of rural, preindustrial Britain; in New Zealand, self-described morals campaigner Patricia Bartlett founded the Society for the Promotion of Community Standards to keep abominations like Clockwork Orange and Deep Throat off cinema and television screens.

But ‘community’ could also be used much more coolly, to describe any collection of individuals or larger social entities. The European Economic Community is the deliberately anodyne, uncontroversial name that Brussels bureaucrats chose for the superstate they began building in 1957.

Whether we understand community in terms of class, culture, geography or some other factor will depend upon the context in which we are encountering or deploying the word, and the way in which we see the world. The meaning of a word like ‘community’ can never be, and should never be, entirely clear.

Geoffrey Hill would be unimpressed by Chis Finlayson’s battle with language.

Although he was elected chair of poetry at Oxford University in 2010, was given a gong at the end of last year, and is now grudgingly described in the mass media as ‘England’s greatest living poet’, the octogenarian Hill remains notorious with many reviewers and readers because of the obscurity and difficulty of his books. In Hill’s poems English words which had seemed friendly and familiar become strange, formidable things, as they recover the various and often opposed meanings they have held during the protracted and bloody history of Albion and its empire.

Geoffrey Hill would be unimpressed by Chis Finlayson’s battle with language.

Although he was elected chair of poetry at Oxford University in 2010, was given a gong at the end of last year, and is now grudgingly described in the mass media as ‘England’s greatest living poet’, the octogenarian Hill remains notorious with many reviewers and readers because of the obscurity and difficulty of his books. In Hill’s poems English words which had seemed friendly and familiar become strange, formidable things, as they recover the various and often opposed meanings they have held during the protracted and bloody history of Albion and its empire.

In interviews Hill has warned about the efforts of politicians and the mass media to clarify and commodify language, and thereby repress history and limit political argument. The poet has insisted that, far from being elitist, difficult writing is radically democratic:

[T]yranny requires simplification…one of the things the tyrant most cunningly engineers is the gross oversimplification of language, because propaganda requires that the minds of the collective respond primitively to slogans of incitement. And any complexity of language, any ambiguity, any ambivalence implies intelligence. Maybe an intelligence under threat, maybe an intelligence that is afraid of consequences, but nonetheless an intelligence working in qualifications and revelations . . . resisting, therefore, tyrannical simplification.

In his poem ‘On Reading Crowds and Power’, Hill found different words to make the same point:

But hear this: that which is difficult

preserves democracy; you pay respect

to the intelligence of the citizen.

Basics are not condescension. Some

tyrants are great patrons. Let us observe

this and pass on. Certain directives

parody at your own risk.

Geoffrey Hill is lucky he doesn’t have to write for Chris Finlayson.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

2 Comments:

I was never quite sure what a 'split infinitive' was until now! Finlayson eh...Yes this is on the theme both of Orwell (who advocated clarity) and the Language Poets who (more or less) court or courted complexity. The ambiguity comes also via 'The Well Wrought Urn' by Cleanth Brooks or via Empson although Brooks was one of the "New Critics"

Paradoxically, there are arguments for and against clarity and also for and against the style of such as Swinburne. The Langpos (somewhat) want to reclaim him.

The argument is also they way we can control or be controlled by language.

There are "innocent" reasons for wanting clarity though. Hill is a poet, but if he was an engineer or technician his use of English would need to be clear. This all starts to lean into the ideas in communication theory (in human terms and in telecommunications etc) which talks about entropy etc. The higher the entropy in system, paradoxically, the more information it contains, the less or the more certain: the less information. Hence it is necessary both in electronic communication systems and human to have more or less redundancy in language. In fact the whole thing is associated with abstruse philosophy that would send such as Finlayson bonkers!

But I don't think it is only Capitalists or free market people who have this issue. There is always a conflict I think between our need for clarity and the desire for degrees of complexity or ambiguity, even magic. Hence riddles and Great Riddlers such as Smithyman!

Hill certainly deserves the accolades.

Hill...elitism personified...

Post a Comment

<< Home