British democracy, and other myths

Scots may be tiring of the Union, but many Kiwis remain keen on Britain. In an article for the conservative New Zealand Initiative, Oliver Hartwich praises the mother country and deprecates its European rivals in language of almost oedipal intensity:

There is something that is undoubtedly special about Britain. It is not just a small, rainy island in the North Atlantic...Other countries may also lay claim to some socio-political developments or scientific inventions, but none other could boast to have started modernity with the same justification...the UK made the modern world, it dominated it until around the time of the Great War, and it still wields incredible soft power to the present day. Britain’s greatness is not just a historic feature. It still makes Britain a special country today...

Hartwich's article is worth reading, because it expresses a belief about Britain common amongst Kiwis on both the left and the right of the political spectrum. Blighty might have bad weather, bad food, and a bad football team, but it apparently managed to produce, at some never-quite-specified point in the past, democratic institutions and ideas, and then spread those institutions and ideas around the world. Constitutional conservatives like Hartwich tend to try to conflate Britain's sclerotic state institutions, like the House of Lords and the Windsors, with this supposed democratic miracle. If a nation like New Zealand attempts to distance itself from Britain, by removing the Union Jack from its flag or Kate and Wills from the covers of its women's magazines, then the spring of democracy will, Hartwich and co warn, run dry.

There is no doubt that Britain was a nursery, in the nineteenth century especially, for progressive ideas and for democratic movements. The struggle for secularism and the Chartist campaign for working class suffrage are notable and noble parts of the country's history.

There is no doubt that Britain was a nursery, in the nineteenth century especially, for progressive ideas and for democratic movements. The struggle for secularism and the Chartist campaign for working class suffrage are notable and noble parts of the country's history.

But these phenomena emerged as reactions to the venality and autocracy of Britain's ruling elite. It was the hegemony of Anglicanism that inspired Quakers, Methodists, and other nonconformists to demand the separation of state and church; it was the arrogance and avarice of the British aristocracy and bourgeoisie in the first decades of the nineteenth century that brought crowds of tens of thousands to the great Chartist demonstrations on heaths and commons.

It is Britain's working class and its religious minorities, not the Windsors or the City of London or the Imperial Army, that we should thank for advancing the cause of liberty.

Britain's ruling class only acquiesced to universal suffrage in the tumultuous period after World War One, when it seemed like millions of returned soldiers might follow the revolutionary example of the Germans and the Russians. And for all the talk of Churchill fighting for democracy during World War Two, the fact is that a large majority of the subjects of the British empire didn’t enjoy the most basic democratic rights in the 1940s.

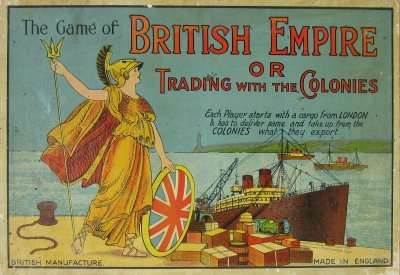

When he talks of Britain 'spreading' freedom around the world, Oliver Hartwich seems to imply that the country's empire was intended as some sort of centuries-long, worldwide class in democracy and civic ethics. A slightly more sophisticated case for the progressive qualities of the British empire is made by Niall Ferguson, in his long, detailed, and persistently obfuscatory 2003 book Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. Ferguson doesn't deny that Britain's empire had its origins in commercial rather than humanitarian interests, but he argues that what was good for British business was ultimately good for the world. In their efforts to grab resources and pacify local peoples, plucky British colonists supposedly brought modern forms of administration and modern notions of citizenship to the world. On these foundations democracy could eventually be built, in societies like India.

But Britain’s favourite strategy for the administration of its colonies – a strategy that was honed over more than a century, and practiced in places as distant and different from one another as Fiji and Nigeria – impeded rather than encouraged economic and social modernisation.

By the twentieth century scholar-administrators of Britain's empire were using the phrase ‘indirect rule’ to describe the way they channelled power through certain traditional authority figures – chiefs, mullahs, petty kings - in their subject societies. Leaders of tribal, ethnic, and religious groups were given dictatorial powers over their local areas in return for loyalty to the British Crown. The result was the deepening of divisions within colonies, and, often, the frustration of attempts at social and economic innovation.

The British mode of colonial administration was justified with the sort of culturally relativist rhetoric – that indigenous peoples had their own ways of life which couldn’t be reconciled with those of the West, that they weren’t suited to democracy, and so on - that conservatives like Niall Ferguson and Oliver Hartwich now like to denounce.

Niall Ferguson would have been better off apologising for French imperialism. The French at least talked about bringing the light of progress to their colonies, and making their African and Asian subjects into dark-skinned Frenchmen and women. They governed in a much more direct way than the British, though no more humanely.

Just as we should credit the development of British democracy to the country's subaltern population, and not to its aristocracy and bourgeoisie, so we should connect the development of democratic institutions in British colonies to the local peoples there, and not to Eton-trained, pith-helmeted viceroys.

It was anti-colonial movements, not colonial administrators, that brought members of different ethnicities, tribes, and religions together. India’s anti-colonial movement eventually splintered along religious lines, but for decades it was a unifying force in the country, linking the various groups - Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Parsees - that the British had tried to isolate.

Indians created their own national representative body, the Indian National Council, in 1885. A mere thirty-four years later, in 1919, the British allowed the creation of a national parliament for India, with the proviso that this body would have no role in the running of either central or local government. A mere sixteen years later, in 1935, India's parliament was given limited powers over local government. This great leap democratic leap forward occurred only because Churchill, who was angrily opposed to any form of Indian self-rule, was outmanoeuvred by others in the Conservative Party and by the Tories’ coalition partners. Independence followed a mere twelve years later, after massive protests, a strike wave, and guerrilla war.

In India as elsewhere, democracy developed in spite rather than because of the British ruling class that Oliver Hartwich wants to defend.

By the twentieth century scholar-administrators of Britain's empire were using the phrase ‘indirect rule’ to describe the way they channelled power through certain traditional authority figures – chiefs, mullahs, petty kings - in their subject societies. Leaders of tribal, ethnic, and religious groups were given dictatorial powers over their local areas in return for loyalty to the British Crown. The result was the deepening of divisions within colonies, and, often, the frustration of attempts at social and economic innovation.

The British mode of colonial administration was justified with the sort of culturally relativist rhetoric – that indigenous peoples had their own ways of life which couldn’t be reconciled with those of the West, that they weren’t suited to democracy, and so on - that conservatives like Niall Ferguson and Oliver Hartwich now like to denounce.

Niall Ferguson would have been better off apologising for French imperialism. The French at least talked about bringing the light of progress to their colonies, and making their African and Asian subjects into dark-skinned Frenchmen and women. They governed in a much more direct way than the British, though no more humanely.

Just as we should credit the development of British democracy to the country's subaltern population, and not to its aristocracy and bourgeoisie, so we should connect the development of democratic institutions in British colonies to the local peoples there, and not to Eton-trained, pith-helmeted viceroys.

It was anti-colonial movements, not colonial administrators, that brought members of different ethnicities, tribes, and religions together. India’s anti-colonial movement eventually splintered along religious lines, but for decades it was a unifying force in the country, linking the various groups - Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Parsees - that the British had tried to isolate.

Indians created their own national representative body, the Indian National Council, in 1885. A mere thirty-four years later, in 1919, the British allowed the creation of a national parliament for India, with the proviso that this body would have no role in the running of either central or local government. A mere sixteen years later, in 1935, India's parliament was given limited powers over local government. This great leap democratic leap forward occurred only because Churchill, who was angrily opposed to any form of Indian self-rule, was outmanoeuvred by others in the Conservative Party and by the Tories’ coalition partners. Independence followed a mere twelve years later, after massive protests, a strike wave, and guerrilla war.

In India as elsewhere, democracy developed in spite rather than because of the British ruling class that Oliver Hartwich wants to defend.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

5 Comments:

Black flag of jihad will fly over London...

http://rt.com/news/166128-isis-jihadists-threaten-britain/

no surprise that ferguson published his book in 2003 - year of the invasion of iraq...empire was in the air

War is like having your body cut open.

If done by a mugger to remove your wallet, it is evil.

If done by a skilled surgeon to remove an inflamed appendix, it is not evil.

The trauma to the body is the same.

The recovery is the same.

Only the intent of the person makes it good or evil.

When you make the war itself evil, you remove the responsibility from the people, and actually make a war more likely.

Niall Ferguson writes well, I read his book about money. He is a conservative (relatively) but he makes sense.

I was looking at some Australian indigenous and art by more recent Aboriginal artists and it occurs that (however it happened, whether there is was the "British Empire") I feel in some ways they were more advanced than the Europeans. Their art in fact and their culture (there is a strange ref. to this in de Lillo's "Ratner's Star' although I forget the details). After thousands of years of living in relative "harmony" with nature and the world and even possibly still being more deeply "in touch" with the mysteries and depth and the reality of nature and ways of living in a difficult environment, what occurred was a slower version of the Holocaust.

The British never quite reached the stage of the SS etc in WWII but all is not well there.

It reminds me, this arrogance of the European Civilisations of the part in Switf's 'Gulliver's Travels' when Gulliver is in among the taller people of Brobdignag and boasts to the King of that place of the great civilisation he has come from with their ability to use great weapons such as gunpowder and guns etc (some of this was, as well as a satire of human stupidity etc, was an attack on Churchill's great grandfather, the warmongering Duke of Marlborough); the King says: "You odious little man...." and proceeds to point out that what he is talking of is absurd and barbarous, he is not impressed with all this "progress"...

And Swift's book remains brilliant and true in many ways.

(He also was one of the first writers to write of a people growing "backwards" in time - it's been done since by Martin Amis in 'The Arrow of Time' I read recently, it deals in a clever way with the paradoxes and horrors of the Holocaust.)

India as a nation also leaves a lot to be desired and their so-called democracy covers a very corrupt backward system - in fact that goes for most places in the world - whereas the Maori, the Australian Aboriginees, lasted for thousands of years in creative interaction (not harmony as such) with their environment, using cooperative ideas and customs. It is possible that the effect of British and other European derived cultures via colonialization has almost caused irreversible destruction of superior cultures.

The destructive effect simply of the cost of the British army in India was enormous and the disruption of the economic and cultural life there was terrible also.

This effect is seen in a parallel way in Iraq or Afghanistan, where, every time the corrupt nation (either the former USSR or the U.S. and its allies such as NZ) invades or interferes, the situation gets worse.

Hi, my name is Olivia Foster. While reading your article, I remembered how I came to Edinburgh for a conference on the problems of historical interpretation of legislative documents. Then I had to urgently find a car hire Edinburgh airport avis. I was lucky to quickly rent a car and I made it in time for the start of the conference.

Post a Comment

<< Home