Wednesday, October 29, 2014

[I 'm grateful to be one of the first two recipients of the D'Arcy Residency, which has been established encourage the writing of long essays about New Zealand's cultural history. Beginning next September, I'll be hunkering down for three months in the D'Arcy cottage on Waiheke Island, and turning out a ten thousand word essay - the core of a book - on New Zealand's role in the nineteenth century Pacific slave trade. I've chosen to head to Waiheke towards the end of next year because I want to get back to the tropical Pacific, and listen again to the kava circles and archives there, before beginning my book.

Here are a couple of excerpts from the synopsis I sent to the committee that awarded the D'Arcy Residencies for 2015, along with some hyperlinks to posts on this blog that have discussed my research into New Zealand's slaving history.]

One day in the winter of 1863, a strange boat

anchored off ‘Ata, a tiny, reefless, rocky island at the southern end of the

Kingdom of Tonga. Although it had spent most of its career hunting whales

in the cold waters around southern New Zealand, the Grecian had recently been painted black

and white, so that it looked like a man ‘o war.

The Grecian's

captain, Thomas McGrath, shouted that he wished to trade with the inhabitants

of ‘Ata, and invited them aboard his vessel. McGrath was an Australian who had

settled in New Zealand, and his crew, a mixture of Pakeha and Maori, had been

recruited in the Chatham Islands.

One hundred and thirty-three 'Atans - almost half

of the population of the island - took up McGrath’s offer, sliding expertly

down cliffs, pushing through the surf, and climbing the side of

the Grecian. They would never see

their homeland again. McGrath and his crew locked the 'Atans in the hold of

the Grecian and sailed to the

northern Cook Islands, where they sold their cargo to slavers bound for Peru.

When he learned of the raid by the Grecian, Tonga's king ordered the evacuation

of 'Ata, and despatched a boat to carry the remaining 'Atans to the much larger, more northerly island of 'Eua. In

a clearing cut from 'Eua's bush, the 'Atans established a settlement that

they named Kolomaile, after the only village on their lost homeland.

Last year, when I

was teaching in Tonga, I visited Kolomaile in the company of Taniela Vao, a lay

minister in the Free Wesleyan church and long-time scholar of his country’s

history. As Taniela and I drank kava, the inhabitants of Kolomaile told stories

about the tragedy of 1863, and described their longing to visit the island

where their ancestors are buried.

The raid on 'Ata was only one episode in a

decades-long slave trade. Peru had banned the

importing of slaves by the middle of the 1860s, but before the end of the

nineteenth century hundreds of vessels carried captives from scores of

Pacific islands to places like Fiji, Queensland, Samoa, and Tahiti. The

traffickers were often called 'blackbirders' or, more euphemistically, 'labour

traders'. Huge and profitable sugar, tobacco, coffee, and cotton plantations were made from their labours.

The similarities between the vanquished American

Confederacy and the colonial plantations of the South Pacific were not

coincidental. After the defeat of the Confederate army and the emancipation of

southern slaves in 1865, plantation owners in the south were ruined. Thousands

of them fled to Mexico, South America, and the Pacific and sought to recreate

the society they had lost. By the end of the 1860s more than two hundred

Americans, many of them former Confederates, were living in Fiji, where they

formed a branch of the Ku Klux Klan and put new slaves to work on new

plantations. Other ex-Confederates became blackbirders, and worked closely with

their New Zealand peers.

'Bully' Hayes, the most famous of all the

blackbirders, was born in America but frequently used New Zealand as his base.

Hayes boasted of his 'adventures' cruising the tropics seizing slaves and

raping women and girls, but he was never molested by New Zealand authorities,

even after he sailed out of Lyttleton in 1869 and kidnapped one hundred and

fifty Niueans to sell to cotton farmers on Fiji...

In May 1870 the slave trade reached the shores

of New Zealand, as the schooner Lulu arrived

in Auckland with a cargo of twenty-seven men from the New Hebridean island of

Efate...

The slave raids of the nineteenth century are

remembered by storytellers and singers in Kolomaile, and in many other Pacific

villages, but they have been forgotten in New Zealand. No statue or plaque

memorialises the tragedies of islands like 'Ata, or the sufferings of the

slaves who landed on the Lulu.

Many Australian historians have written about the importance of blackbirding to

Queensland's economic development, but few Kiwi

scholars have discussed our country's slaving history.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries, though, New Zealand's popular culture was full of references to men

like Bully Hayes. The raids that Hayes and his peers made on tropical islands

and the battles they sometime fought with islanders were romanticised and

celebrated in songs, poems, and popular histories. Louis Becke wrote

bestselling accounts of the life of Hayes; WB Churchward's Blackbirding in the South Pacific appalled

and titillated Victorian audiences with its gore.

By putting the stories told by the people of

Kolomaile and other Pacific communities alongside the forgotten texts produced in nineteenth

century New Zealand, I want to view this sad and salutary chapter in our

history from two sides. After describing the most important events in the

blackbirding era and introducing some of the actors in the drama, I want to

explain the ways that both the storytellers of villages like Kolomaile and the

palangi writers of the Victorian era perceived and presented events like the

raid on 'Ata...

The slave trade of

the nineteenth century finds eerie echoes in the twenty-first century. The

Recognised Seasonal Employment Scheme, which has in recent years seen thousands

of Tongans and other Pacific Islanders come to New Zealand and Australia to

work for low wages without offering them any chance of permanent residency, has

been condemned by some Polynesian leaders as racist and exploitative. In a

television debate held during New Zealand’s 2014 election campaign, Hone

Harawira characterised the scheme as a form of ‘slavery’.

In a series of

articles that were published in the Sunday

Star Times in 2011 and eventually prompted a government investigation and

legislation, journalist and historian Michael Field revealed that the Asian and

Pacific Island crews of some ships fishing in New Zealand’s territorial waters

were being beaten, denied adequate food, and paid derisory wages. Field likened

the workers on these ships to slaves.

When we realise that

New Zealand was deeply involved in a nineteenth century slave trade, then the

abuses documented by Simon Field and the restrictions placed on contemporary

migrant labourers can be seen in a new perspective.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Thursday, October 23, 2014

Art and the Occupy generation

My essay about the Tongan-New Zealand performance artist 'Ite 'Uhila, who lived rough on Auckland's streets over winter, has provoked a few discussions since it was published last week at EyeContact.

'Uhila's street performance, which was called Mo'ui Tukuhausia, was one of the four artworks to make the shortlist for this year's Walters' Prize, but missed out to Luke Willis Thompson's equally controversial inthisholeonthisislandwhereiam.

Thompson's work saw visitors to a gallery space being led by a security guard down a long corridor and delivered to a taxi driver, who in turn took them to the home of the artist's mother, where they were invited to look about.

Over on facebook, one commenter used my essay to draw a contrast between 'Uhila and Thompson. According to her, Thompson's work was 'weak and washed out' compared to Mo'ui Tukuhausia, and only won the Walters Prize because of the racism of the New Zealand art world.

Here's the response I made on facebook:

I agree that there is a lack of knowledge about the cultural and historical contexts in which many Tongan artists work amongst Pakeha who visit galleries and museums, and I think that this lack of knowledge probably contributed to the failure of 'Ite to win the Walters. There's an irony in the way that Pakeha interested in the arts, as students or practitioners of critics, will devour difficult, often convoluted texts by European intellectuals - Derrida and Zizek and Baudrillard and so on - but won't consider the work of Pasifika intellectuals like, say, Futa Helu or Epeli Hau'ofa, or learn about the traditions within which, say, ngatu artists work, because that stuff is - to quote the sort of words I've heard used - too 'alien' or 'esoteric'! I understand these contradictory attitudes, because I used to harbour them myself.

I'm not sure I agree with you, though, when you try to make a dichotomy between 'Uhila and Luke Willis Thompson, and suggest that Thompson was much less deserving of the Walters than 'Ite.

It seems to me that 'Ite and Thompson's shortlisted works had several things in common. Both were attempts to steer their audiences away from the art gallery, both were questioning where the boundary between art and the rest of the world lies, and both seemed, to me at least, to be making critical statements about the way Niu Sila society operates.

'Ite threw away the artist's normal repertoire of tricks, abandoned the gallery, became a haua, and tried to show that some of the virtues we see in artists, and in other esteemed members of society, are also present in the despised homeless on our streets, if only we would look.

For his part, Thompson forced visitors out of the safe, antiseptic space of the gallery, led them to a cool, slightly rundown, and eerily empty home, and seemed to ask them to meditate on the relationship between the everyday world in which we live and the tidied up, beautified world of art and the art gallery.

I think that 'Ite and Thompson are both artists who belong to a generation that is questioning, in a perhaps inchoate way, the verities of market capitalism and runaway technology, and seeking some more authentic way of being in the world. We might perhaps, call theirs the 'Occupy Generation', after the protesters who tried to bring direct human interaction to the alienated wildernesses of our central cities. I certainly see something of the idealism of the Occupy protesters in the methods of both 'Ite and Thompson. Both seem to want to break down the walls between artist and audience and art and life, and substitute human intimacy for the formal operations of galleries and the art market.

In the discussion thread underneath my piece about 'Ite for EyeContact, I've argued that there are some risks involved in trying to get rid of the distinctions between art and life and artist and audience. As you can see, Daniel Webby disagrees with me.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

'Uhila's street performance, which was called Mo'ui Tukuhausia, was one of the four artworks to make the shortlist for this year's Walters' Prize, but missed out to Luke Willis Thompson's equally controversial inthisholeonthisislandwhereiam.

Thompson's work saw visitors to a gallery space being led by a security guard down a long corridor and delivered to a taxi driver, who in turn took them to the home of the artist's mother, where they were invited to look about.

Over on facebook, one commenter used my essay to draw a contrast between 'Uhila and Thompson. According to her, Thompson's work was 'weak and washed out' compared to Mo'ui Tukuhausia, and only won the Walters Prize because of the racism of the New Zealand art world.

Here's the response I made on facebook:

I agree that there is a lack of knowledge about the cultural and historical contexts in which many Tongan artists work amongst Pakeha who visit galleries and museums, and I think that this lack of knowledge probably contributed to the failure of 'Ite to win the Walters. There's an irony in the way that Pakeha interested in the arts, as students or practitioners of critics, will devour difficult, often convoluted texts by European intellectuals - Derrida and Zizek and Baudrillard and so on - but won't consider the work of Pasifika intellectuals like, say, Futa Helu or Epeli Hau'ofa, or learn about the traditions within which, say, ngatu artists work, because that stuff is - to quote the sort of words I've heard used - too 'alien' or 'esoteric'! I understand these contradictory attitudes, because I used to harbour them myself.

I'm not sure I agree with you, though, when you try to make a dichotomy between 'Uhila and Luke Willis Thompson, and suggest that Thompson was much less deserving of the Walters than 'Ite.

It seems to me that 'Ite and Thompson's shortlisted works had several things in common. Both were attempts to steer their audiences away from the art gallery, both were questioning where the boundary between art and the rest of the world lies, and both seemed, to me at least, to be making critical statements about the way Niu Sila society operates.

'Ite threw away the artist's normal repertoire of tricks, abandoned the gallery, became a haua, and tried to show that some of the virtues we see in artists, and in other esteemed members of society, are also present in the despised homeless on our streets, if only we would look.

For his part, Thompson forced visitors out of the safe, antiseptic space of the gallery, led them to a cool, slightly rundown, and eerily empty home, and seemed to ask them to meditate on the relationship between the everyday world in which we live and the tidied up, beautified world of art and the art gallery.

I think that 'Ite and Thompson are both artists who belong to a generation that is questioning, in a perhaps inchoate way, the verities of market capitalism and runaway technology, and seeking some more authentic way of being in the world. We might perhaps, call theirs the 'Occupy Generation', after the protesters who tried to bring direct human interaction to the alienated wildernesses of our central cities. I certainly see something of the idealism of the Occupy protesters in the methods of both 'Ite and Thompson. Both seem to want to break down the walls between artist and audience and art and life, and substitute human intimacy for the formal operations of galleries and the art market.

In the discussion thread underneath my piece about 'Ite for EyeContact, I've argued that there are some risks involved in trying to get rid of the distinctions between art and life and artist and audience. As you can see, Daniel Webby disagrees with me.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Monday, October 20, 2014

Fantasy islands

Apostles of digital reality sometimes claim that everything in the world, and a little more besides, exists on the internet, but the web seemed to me a terribly incomplete place - a poor copy of reality, like the shadows that trembled on the wall of Plato's cave - without this map, which I've scanned from Tin Can Island, CR Ramsay's 1938 book about Niuafo'ou, the regularly active volcano in the far, semi-fabulous northern zone of the Kingdom of Tonga.

Ramsay ran Niuafo'ou's store and designed its postal system, which saw muscled young men holding cans full of postcards and letters above the water while they swam to passing cargo ships.

When I look at Ramsay's map of Niuafo'ou, I can't easily separate fact from fantasy. For a distant admirer like me, the island's warm crater lake, which contains islands and an island lake of its own, seem as impossibly marvellous as the cherub who wheezes in the map's northwestern corner.

My older son has his own fantasy island. He is convinced that Rangitoto - or Langitoto, as the Tongans, whose tongues do not like the trill of the letter 'r', call it - is, along with Indonesia's Komodo Island, the chief habitat of the world's relict dinosaurs.

I grew up commanding armies of stunted toy soldiers and fighting with stick guns for the ditch-trenches of the family farm, but my wife has banned me from making our children into militarists. When he sees a gun on television or in a cast-off piece of newspaper, my son has learned to call the strange device a telescope.

When Aneirin and I recently climbed that most fabled and tunneled of Auckland's hills, Maungauika/North Head, and discovered a large gun near the northern summit, pointing towards Rangitoto, he decided, quite reasonably, that it was a telescope made to help visitors 'spy on the dinosaurs' of the nearby island. He looked down the barrel of the instrument and began to describe the fantastic creatures of Rangitoto.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Ramsay ran Niuafo'ou's store and designed its postal system, which saw muscled young men holding cans full of postcards and letters above the water while they swam to passing cargo ships.

When I look at Ramsay's map of Niuafo'ou, I can't easily separate fact from fantasy. For a distant admirer like me, the island's warm crater lake, which contains islands and an island lake of its own, seem as impossibly marvellous as the cherub who wheezes in the map's northwestern corner.

My older son has his own fantasy island. He is convinced that Rangitoto - or Langitoto, as the Tongans, whose tongues do not like the trill of the letter 'r', call it - is, along with Indonesia's Komodo Island, the chief habitat of the world's relict dinosaurs.

I grew up commanding armies of stunted toy soldiers and fighting with stick guns for the ditch-trenches of the family farm, but my wife has banned me from making our children into militarists. When he sees a gun on television or in a cast-off piece of newspaper, my son has learned to call the strange device a telescope.

When Aneirin and I recently climbed that most fabled and tunneled of Auckland's hills, Maungauika/North Head, and discovered a large gun near the northern summit, pointing towards Rangitoto, he decided, quite reasonably, that it was a telescope made to help visitors 'spy on the dinosaurs' of the nearby island. He looked down the barrel of the instrument and began to describe the fantastic creatures of Rangitoto.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

Spitting on the artist

The pressure began almost as soon as the artist had opened his exhibition. Sitting outside the gallery in the sun, he was confronted by a series of angry men and women. Several of them swore at him; one of them spat on him. Other unhappy citizens wrote complaints to the gallery, urging it to repudiate the artist.

On three separate occasions, members of the police force confronted and interrogated the artist. During the last of these grillings, the artist handed his inquisitors a letter from the gallery's manager, which explained the institution's support for his work. A policeman tore the piece of paper up, and the artist decided that the time had come for him to end his show.

The events I've been described didn't occur in Solzhenitsyn's Soviet Union, or in the Ayatollahs' Iran, but in the east Auckland suburb of Pakuranga, where Kalisolaite 'Uhila performed Mo'ui Tukuhausia, or Living Homeless, for two weeks in 2012.

We New Zealanders like to consider ourselves a tolerant, enlightened people. We chuckle when we see the televangelists of America or the mullahs of the Middle East condemn a pop song with naughty lyrics or a film with nude scenes as an insult to the Almighty; we shake our heads when we read about the arrest of demonstrators demanding democracy in China.

When Kalisoliate 'Uhila donned the tattered black uniform of a tramp and took up residence in the grounds of Te Tuhi gallery, though, he soon showed the limits of our tolerance and enlightenment. The sanctity of private property; the separation of our private, embarrassingly intimate, and public, respectable lives; the moral necessity of work: all of these solemn principles of our society seemed mocked by the silent man in black.

This year Mo'ui Tukuhausia was nominated for the Walters Prize, New Zealand's most prestigious art award. At the request of the Auckland City Art Gallery, Kalisoliate 'Uhila has just finished a three month reprise of the work that made him a familiar and sometimes controversial figure on the pavements and in the parks of our central city. In the latest of my series of essays for the online arts journal EyeContact, I've tried to counter the criticisms that 'Uhila has faced, and linked his performances with some of the radical intellectual and artistic traditions of his native Tonga.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

On three separate occasions, members of the police force confronted and interrogated the artist. During the last of these grillings, the artist handed his inquisitors a letter from the gallery's manager, which explained the institution's support for his work. A policeman tore the piece of paper up, and the artist decided that the time had come for him to end his show.

The events I've been described didn't occur in Solzhenitsyn's Soviet Union, or in the Ayatollahs' Iran, but in the east Auckland suburb of Pakuranga, where Kalisolaite 'Uhila performed Mo'ui Tukuhausia, or Living Homeless, for two weeks in 2012.

We New Zealanders like to consider ourselves a tolerant, enlightened people. We chuckle when we see the televangelists of America or the mullahs of the Middle East condemn a pop song with naughty lyrics or a film with nude scenes as an insult to the Almighty; we shake our heads when we read about the arrest of demonstrators demanding democracy in China.

When Kalisoliate 'Uhila donned the tattered black uniform of a tramp and took up residence in the grounds of Te Tuhi gallery, though, he soon showed the limits of our tolerance and enlightenment. The sanctity of private property; the separation of our private, embarrassingly intimate, and public, respectable lives; the moral necessity of work: all of these solemn principles of our society seemed mocked by the silent man in black.

This year Mo'ui Tukuhausia was nominated for the Walters Prize, New Zealand's most prestigious art award. At the request of the Auckland City Art Gallery, Kalisoliate 'Uhila has just finished a three month reprise of the work that made him a familiar and sometimes controversial figure on the pavements and in the parks of our central city. In the latest of my series of essays for the online arts journal EyeContact, I've tried to counter the criticisms that 'Uhila has faced, and linked his performances with some of the radical intellectual and artistic traditions of his native Tonga.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Monday, October 13, 2014

Sir, there is dry rot in the Labour Party

In the second half of 2010 I spent a few hundred hours in the archives of the University of Auckland library, exploring the forest of Kendrick Smithyman's unpublished poems one tobacco-yellow, wine-stained leaf at a time. I collected several dozen of Smithyman's 'lost' poems in a book called Private Bestiary, but many had to be left in the wilds of the archive. 'Dry Rot in the Labour Party' didn't make my publication list in 2010, but its title has been echoing in my head lately. You can guess why.

Smithyman wrote the poem in 1951, the year when Labour, under the leadership of Stuart Nash's great grandfather, was struggling to remain on the sidelines of the Great Waterfront Lockout, a battle between the National government of Sid Holland and the militant section of the trade union movement led by wharfie Jock Barnes.

Labour's failure to support Barnes and his comrades had been forseen by a young man named Robert Blake. In 1950 Blake had used an article for Here and Now, a small magazine linked to the Communist Party of New Zealand, to accuse Labour of abandoning its socialist policies in return for political respectability, and of betraying its allies in the trade union movement. Blake's article was called 'Dry Rot in the Labour Party'.

Smithyman was an occasional contributor to Here and Now, and had espoused communist politics in some of the letters and poems he wrote from various barracks during World War Two. But his poem seems, to me at least, like a satire of Kiwi intellectuals who tried, in the unpropitious conditions of post-war New Zealand, to combine support for communism with a bohemian lifestyle and avant-garde tastes in the arts. As Smithyman takes the mickey out of Robert Blake and co., he offers a portrait of a cultural and political world that disappeared decades ago.

Leave your interpretations in the comments box.

Dry Rot in the Labour Party

Sir, I am my own man thinking my own thoughts,

not blown about by merely a popular wind

IS DRY ROT IN THE LABOUR PARTY

I come to my own conclusions without respect

to orthodoxy or heterodoxy, I find my way

believing

Read and relaxation are right for child-bearing

Margaret Mead is right for the anthropologist

political truth somewhere between Burnham and Bukharin's

DRY ROT IN THE LABOUR PARTY DRY ROT PARTY

Landfall is stodgy but Here and Now has purpose,

Weeks is the best painter in New Zealand,

recently I bought Lee-Johnsons, now I buy Patersons,

the Listener film notes aren't what they used to be,

we need ballet and opera and have a Recorded

Music Society to which I do not belong

although it is there if I want to belong to any

PARTY DRY PARTY DRY LABOUR

I discriminate in my jazz: I know some of the names

of some of the cats on the old platters and also

I know Derek who blows a mean licorice stick.

The National Symphony Orchestra? Always

the National Symphony Orchestra even if honestly

sometimes, you know,

I like Cary's novels

but I don't think I should like Carew's novels

because there is

DRY ROT

and Sargeson. Sargeson writes good short stories

though his novels aren't novels and the Labour Party does

not labour.

Next year I shall probably return to

Trollope since H. James I do not wish to read again -

still there is Eliot and the

Cocktail

PARTY DRY PARTY

When I'm out at a party I drink beer.

Occasionally I make my own, I am not a brewer's lackey.

In the last three years I have known three interesting

families: Poppelbaum's, Vrcjmskuch's, and mine

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Saturday, October 11, 2014

The return of the 'now'

[Roger Horrocks, legendary chronicler and contributor to New Zealand culture and author of the neglected psychogeographic masterpiece Auckland Regional Transit Poetry Line, which records his adventures on this city's buses in the early 1980s, has let me publish the text of a talk he gave last Thursday night at the launch of Murray Edmond's book Then It Was Now Again: Selected Critical Writing.]

The thing I want to get across is

that this is a unique book, an extraordinary book – not only because it’s

beautifully produced but because it holds the essence of a lifetime of thinking

about poetry, theatre, cultural politics, and the situation of living in New

Zealand.

I’m overjoyed that such a collection

can still be written and published in this country – it stands in utter

contrast to today’s verbal fast-food, the “over-hasty volumes [of] blurb and

guff” (to borrow one of Murray’s phrases), would-be best-sellers ghost-written

by the invisible hand of the market.

Murray’s Big Black Book is the real

deal, an essential guide to our past, present and future. The title, a phrase

from Janet Frame, covers that whole kit and caboodle - “Then it was Now Again”

– echoing the time-travel in the title of Murray’s doctoral thesis, “To my Old

Comrades of the Future.” Revolutions of the past look expectantly to new

revolutions tomorrow.

There are over 40 years documented in

this collection. Today we have an urgent need for good critical history. I was

talking the other night with a former colleague who observed that students are

displaying an ever-shrinking sense of history. Technology is moving so fast

that five years is now a distant horizon for them. So there’s relevance in

launching this book in a pub dedicated to an Elizabethan poet and theatre man.

Murray is always interested in the

big picture, though he also makes lovely detailed readings of particular texts. And if I seem to be making this book

sound too serious and earnest, I should add that it is a hugely entertaining

read. He describes the writer’s role as “a wrestling match with his own culture

and the language it has debased.” For that kind of wrestling, Murray is a

Superstar and he grapples with many flabby or pretentious forms of culture. For example, he says of mainstream theatre:

“Groups need good audiences to survive, but NZ theatres are invariably choked

with the stuffy and the stuffed who cannot be shocked or overjoyed, who cannot

laugh, and who love it all, [who]

thank Christ they are here, safe in furs, and not out there threatened on the

street.”

Of a would-be avant-gardist he

writes: “I must point out…that all this postmodern posturing is just the shadow

of a new orthodoxy and it is there to mask and hide the fact that the language

is quite lifeless.” (Language is always one of Murray’s touchstones.) And of a

reviewer in NZ Books: “Her

demonstration of a lack of basic literary general knowledge, her inability to read tone, and her

inattention to form and measure…-[these things are] trumpeted by her review,

they are badges she wears with pride.” Such takedowns are only a warmup for when

Murray gets in the ring with more vicious opponents such as Rogernomics.

In covering 40 years of NZ cultural history he identifies various

bursts of “revolution” which were then tamed and domesticated by the establishment.

Equilibrium was regained, establishing a new “staid parade” (so that “Now”

became “Then”). But “now” can surge back up in a new form. Murray traces its

ups and downs as a canny historian who is always looking for new energies but

at the same time understands the complexities, ironies and naive “Romantic

streak” that are a part of any revolution. In the Big Smoke days of the ’70s,

for example, he notes: “There were elements of the messianic, the insane, the

magical and irrational in the poetics of the period” – he is completely

clear-sighted about that, but in poetry and theatre he still deeply respects

the search for “Paradise,” “utopia,” or “revolution as carnival.” Murray is a brilliant critic, rare in our

culture, who has never lost his appetite for openness, for experiment and risk,

for “making it new”. No doubt it helps that he has remained such an active creative figure, always on the

front lines.

In short, this book is history we need

– it’s the tale of our tribe in its efforts to (quote) “transform a

colonial society and its brutalisations into something else.” Murray has (in the

words of one essay title) managed to catch “the terror and the pity,” the

humour and surprises of it. In my opinion this is not merely an excellent book

but an essential book that every serious New Zealander

must buy – and start wrestling with.

-Dr Roger Horrocks

Wednesday, October 08, 2014

Speaking over Heaphy

Here are another couple of excerpts from my introduction to Murray's book. I'll see you tomorrow night, and shout you a Rheineck.]

At the end of the sixties and the beginning of the seventies, Murray Edmond was one of a gang of young literary rebels who published a magazine called The Word is Freed, or Freed for short, from their base in inner city Auckland. Like many writers of their generation, the Freed group considered cultural and political radicalism to be inextricably connected. The Fordist capitalist societies of the postwar West, with their vast and orderly factories, quiescent working classes, and smug, bureaucratised political parties, seemed to depend for stability on a puritanical morality and a philistine mass culture. Seduced into conformity by their televisions and by well-stocked supermarkets, and fearful of the consequences of sexual and chemical experimentation, the denizens of the West needed to change their lifestyle as well as their politics.

For the Baby Boomers who marched and rioted in the streets at the end of the sixties, culture was therefore as much an issue as economics and politics. During the revolutionary ‘May Days’ of 1968, the students and workers of France demanded the end of sexual and cultural repression as well as common ownership of the economy, and painted the slogan TOUT LE POUVOIR A L’IMAGINATION (ALL POWER TO THE IMAGINATION) on walls. Poets, it seemed, were in the vanguard of the revolution.

The exuberantly innovative poems published in Freed were intended, then, as a challenge to New Zealand society, as well as to New Zealand literature. In the first issue of the magazine, Alan Brunton condemned the notion of art for art’s sake, insisting that ‘A WORK OF ART HAS NO RIGHT TO LEAD AN AUTNOMOUS MORAL EXISTENCE’ inside a world that is too often ‘DIVORCED FROM THE VALUE OF HUMAN LIFE’.

As Murray Edmond notes in his preface to this book, though, the coupling of revolutionary politics and revolutionary art did not last long. In the eighties Thatcher, Reagan, and our own Roger Douglas brutally restructured capitalism, shrinking the state, shutting factories, splintering the left, and inaugurating a post-Fordist era in which an atomised population competed for insecure service sector jobs. At the same time, the cultural phenomena that had seemed aberrant and dangerous in the sixties – sex outside marriage, communal living, alternative religions, rock festivals, independent film making, and so on – were accepted and commercialised by most Western societies. The counterculture became a set of unthreatening subcultures...

Theatre occupies a special place in this book, and a special place in Edmond’s life. He has worked as a dramaturge, theatre director, and teacher of drama, and mentored generations of playwrights and actors. Edmond sees the theatre not as some autonomous zone where the contradictions of quotidian life are dissolved, but as a site where contradictions and the conflicts they produce can be experienced and examined. Edmond shows us the conflicts that can arise between playwright and director, director and actors, and actors and audiences, and links these clashes to conditions in the world outside the playhouse. The aesthetic success of any theatrical venture depends, Edmond suggests, on the acknowledgement and creative use of contradictions. A successful theatrical performance is a model, however small-scale and temporary, of a democratic society, where differences are acknowledged rather than evaded or repressed.

The long, eponymous essay that concludes this book has an elegaic tone that contrasts poignantly with the brusque optimism of some of Edmond’s youthful writings. Where the proclamations of Freed looked forward to a revolutionary future, ‘Then It Was Now Again’ looks backwards, deep into New Zealand’s past, and laments the way that successive propagandists for the powerful, beginning with the nineteenth century surveyor Charles Heaphy, have tried to write inconvenient individuals and communities out of history. Edmond presents New Zealand writing as a continual joyous struggle to salvage and restore the memory of marginalised people and forgotten events.

The style of ‘Then It Was Now Again’ perfectly matches the essay’s argument.

As he refutes the simplified versions of New Zealand history produced by men like Heaphy, Edmond offers quotations, in English and Maori and a strange hybrid of the two languages, from more than a dozen authors. Historians like Judith Binney and James Belich are quoted alongside poets like Smithyman and Robin Hyde and the nineteenth century prophet Te Ua. Several authors whose names have been lost – footsoldiers in the anti-imperialist wars of the nineteenth century, who left their words of defiance hanging in the air like gunsmoke – join the fray.

For Murray Edmond, history is a democratic, and often contradictory, polyphony of voices, rather than some smooth monologue. We can be thankful that Edmond has added his voice to New Zealand literature over the past four decades.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Monday, October 06, 2014

Inside the Seleka Club

Last Thursday, after being directed to a barren public park by a series of text messages, I was handed a large untitled painting by Tevita Latu, the founder and spiritual leader of Tonga's Seleka Club, whose members sit up all night, almost every night, drinking kava from a toilet bowl and making provocative art.

Latu's painting was brought to Niu Sila by art mule Tui Emma Gillies, who recently visited Tonga to stock up on tapa cloth and dye and to drink kava with the Selekarians. I hope that, like its predecessors, the painting will act as a magical portal from a still-chilly Auckland to the permanent summer of Tongatapu.

A fragment of film showing Tui Emma Gillies inside the hallowed coconut trunk walls of the Seleka Club has turned up on Youtube. She and the Selekarians appear to be beautifying some rubbish bins kidnapped from the streets of Nuku'alofa.

Wednesday, October 01, 2014

Glenn Jowitt's secret societies: notes on two photographs*

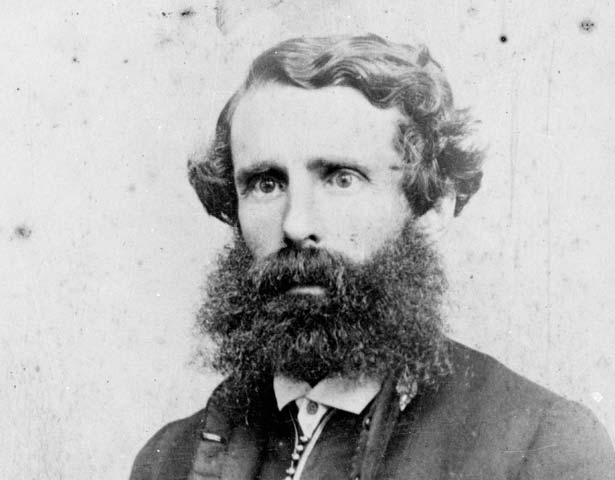

Glenn

Jowitt, who died at the end of July, loved to

discover and document secret societies and secluded worlds. Jowitt is justly

famous for the photographs he took during his travels through the tropical

Pacific in the 1980s and ‘90s, but I wanted to praise two images that he made

very early in his career.

While he was

a student at Ilam Art School in the late 1970s, Jowitt became preoccupied with

horse racing, and began to travel with his camera to courses around Canterbury.

With its elaborate rules, bizarrely named animals, erudite, laconic tipsters, and conspiratorial

trainers and jockeys, the racing industry was and remains a society within New

Zealand society.

This

portrait of a Canterbury jockey appeared in Jowitt’s first book, Racing Day. With his youth, his pallor,

and his dirty face, the jockey might remind us, at first sight, of the

chimneysweeps or underage coal miners preserved in nineteenth century daguerreotypes.

But where those victims of Victorian commerce offered aimed weary and

embarrassed gazes at their pitying photographers, Jowitt’s jockey looks

haughtily down at the camera. He is proud of his role in the world Jowitt has

entered, and he needs nothing from the photographer or the photographer’s

audience. He wears the fresh racetrack mud in the same way that a young man in

another culture might wear war paint.

After

graduating from Ilam, Jowitt began to photograph another secret society. He

spent months drifting across Canterbury with members and associates of Black

Power, which had become, by the beginning of the 1980s, New Zealand’s biggest gang.

An astonishing series of photographs shows gang members journeying out of

Christchurch and into the empty spaces of the Canterbury Plains.

The flat

countryside of Canterbury has often posed problems for the Pakeha imagination.

Even before the arrival of pyromaniacal European settlers, the Plains had lost their

forests to fire. As they looked westward from the tight little colonial town of

Christchurch, colonists were troubled by the emptiness that separated them from

the Southern Alps. The peaks and glaciers and valleys of the Alps could be

safely praised, in Wordsworthian language, for their Sublimity, and happily

sketched and painted by weekend excursionists. The formless flatlands, though,

were harder to assimilate. Colonial diarists deplored their ‘desolation’.

Driven by

psychological and well as economic needs, imperial planners drew straight lines

across maps of Canterbury. Crops and stock were raised on rectangular and

triangular farm blocks; hedges and gothic churches were planted, as guardians

against the tormenting emptiness.

By the time

John O’Shea made his road movie Runaway

in 1964, Pakeha audiences could consider the Canterbury Plains a cosy, calm

place. Taking a stolen car across the lush, flat twilit farms of Canterbury on

his way to the Southern Alps, the protagonist of Runaway enters a sort of trance, and believes that he is flying

rather than driving his machine.

But one

culture’s paradise can be another’s desert. For their former owners, the Plains

had become, by the second half of the twentieth century, an alien landscape.

Ancestral rivers had been straightened into drains; lamprey weirs had been

replaced by pumphouses; willows had usurped flax bushes; NO TRESPASSING signs

frustrated old pathways. For Black Power members habituated to the boozy

solidarity of Christchurch’s seedier clubs and pubs, the Plains must have seemed

empty and exposed.

This

photograph is called Devil and Baldie,

after its protagonists. Running out of road, the two gang members have driven

across an expanse of grass. Have they stopped deliberately or broken down, at

this apparently random spot in the middle of a paddock? The Southern Alps are a

line of low hills on the horizon. The sky might have turned grey with age.

Devil seems

reluctant to leave the safety of the car. He hunches by one of its open doors,

hiding under his Afro. It is left to Baldie, who has been identified by other

photographs as a senior member of Black Power in Canterbury, to walk into the

emptiness.

Baldie wears

a cowboy hat, but he has arrived in this landscape too late: the frontier has

been closed, the title deeds have been drawn up, hedges and fences and police

stations have been raised, and an outlaw can hope to find neither refuge nor

riches.

Jowitt’s

jockey exists safely inside his alternate society; Devil and Baldie, by

contrast, have been separated from the sanctuaries and rituals of their world,

and given to a strange and malicious landscape.

*This post

began as yet another attempt to write something for hashtag500words, the website

set up last year by the artists and curators Louisa Afoa and Lana Lopesi. As

its name suggests, Afoa’s and Lopesi’s site limit its contributors to five

hundred words. I’ve now run hopelessly over that word limit three times; as a

failed student of the haiku, I should have known that I’d lack the concision

that Afoa and Lopesi require. Take a look at hashtag500words anyway.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]