Thursday, February 26, 2015

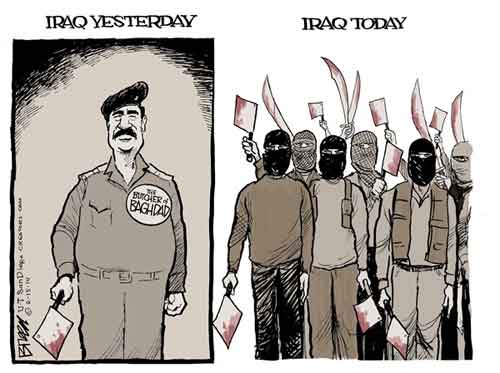

Chanting

Koranic verses, the army of a grandiose leader conquers a piece of desert and a

few towns, and proclaims these possessions a caliphate. Muslim prisoners of war

and infidel interlopers are executed in horribly ingenious ways, and in the

cities and barracks of the West politicians and generals demand a response. As

expeditionary forces are assembled in Britain, North America, and Australia,

New Zealanders debate whether they should join the war in the desert.

This

narrative might fit with the events of the last few months, but it also describes the dramas of 1884 and 1885, when a Sudanese nationalist calling himself

the Mahdi, or messiah, pushed Egyptian and British troops out of his homeland,

and made Khartoum the capital of a state that he hoped would eventually cover the world. The British general Charles Gordon, who struggled unsuccessfully

against his own messianic delusions, was decapitated after refusing to retreat

from Khartoum.

New

Zealanders may have lacked social media and television in the 1880s, but they

followed events in the Sudan tenaciously. Newspapers carried long commentaries

on the fighting, and in a hall in the military settlement of Hamilton a diorama made with sand dunes and toy soldiers showed crowds of visitors a battle

between the Mahdi’s army and the British.

During

the first months of 1885 hundreds of volunteers learned to march and salute and

shoot in a Sydney barracks, as the government of New South Wales pledged its

support for the battle to retake the Sudan. But John Ballance, Defence Minister of

New Zealand, was uninterested in doing his bit for the empire. When a retired

colonel of the British army wrote to ask him whether New Zealand would be sending

an army to Sudan, Ballance responded negatively, explaining that his sympathies

were with the Mahdi, rather than with the British.

In Paradise Reforged, his history of New

Zealand from the 1880s to the end of the twentieth century, James Belich argues

that Ballance’s refusal to send troops to the Sudan was not some personal

eccentricity, but the reflection of a distrust of Britain widespread amongst

Pakeha New Zealanders in the 1870s and ‘80s. Men like Ballance had been born in

Britain, knew about the inequities and hypocrisies of the place, and had

crossed the world to create a new homeland for themselves. For them, New

Zealand was a ‘Greater Britain’ which would, like the United States before it,

become economically and politically free of the old country.

John Ballance

was not some enlightened anti-imperialist – he hated Maori, and had fomented

and fought in the Taranaki War of the late 1860s. But Ballance lacked the

loyalty to and awe of the British monarchy and empire that had led Charles

Gordon to martyrdom in the Sudan.

The

story of John Ballance’s response to the war in Sudan might have surprised

Philip Hammond, who is the Foreign Secretary in today’s British government.

During a recent visit to Wellington, Hammond explained that New Zealand ought

to contribute to the new war in Iraq because we are ‘part of the family’ that

includes Britain, the United States, and Australia. Britain has, Hammond said,

gotten ‘used to’ New Zealand ‘being there alongside us’ when wars are fought.

Hammond

was referring, of course, to the Kiwi troops who have fought and died during

two world wars and a series of smaller conflicts, like the battle against

communists in Malaya and the long struggle against Pashtuni nationalism in

twenty-first century Afghanistan.

But

Philip Hammond’s argument did not resonate with New Zealand politicians.

Cabinet Minister Peter Dunne is not known as a radical anti-imperialist, but in

an angry speech to parliament he described Hammond as ‘a patronising figure

from abroad’ who wanted to lead New Zealanders into a new ‘round of unmitigated

slaughter’.

John

Key’s recent decision to send troops to Iraq has been condemned by the forces

of the left, but also by conservatives like Dunne, the Maori Party’s Te Uruora

Flavell, and Winston Peters. For the critics, New Zealand’s new military

adventure is a pointless show of loyalty to the United States and Britain.

James

Belich explained New Zealand’s twentieth century enthusiasm for the British

Empire and its wars by pointing to changes in the country’s economy that began late

in the nineteenth century. After the advent of refrigerated shipping and the

beginning of mass exports of beef and lamb to Britain, New Zealand became

economically dependent on the old country, and conservative farmers came to

dominate the nation’s politics and culture. Links with Australia and other

parts of the Pacific were half-forgotten, and Pakeha New Zealanders, at least,

began to consider themselves residents of a misplaced fragment of Britain. When

Britain itself came under the domination of the United States after World War

Two, New Zealand became an obsequious ally of Washington, as well as London.

Britain’s

economic influence over New Zealand has evaporated over the past forty years,

and during the last decade and a half China has usurped the United States as an

export market for Kiwi farmers. The rise of China and disastrous failure of

George Bush’s attempt to remake the Middle East show that, like Britain sixty

years ago, the United States is a declining power. The opposition to the new

military adventure in Iraq from mainstream politicians like Peter Dunne and

Winston Peters is a harbinger of a future where New Zealand governments no

longer march in step with the United States and Britain. The nationalism

of John Ballance is making a comeback.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Friday, February 20, 2015

Exhibitionism: a quick guide for the offended

With the encouragement of the Young Men's Christian Association, the Taxpayers Union, and various bloggers, thousands of people have signed a petition denouncing the exhibition of an obscene T shirt at Canterbury Museum.

The shirt, which was produced to promote the heavy metal band Cradle of Filth and shows a nun masturbating as well as the slogan JESUS IS A CUNT, was banned from New Zealand in 2008. Canterbury museum's curators got special permission to show it - in a secluded, adults-only room - as part of an exhibition called T Shirts Unfolding. The museum wants its visitors to think about the limits to freedom of speech, and about the functions of censorship. The YMCA and co argue that the T shirt is offensive, and that museums should not display offensive objects.

I've been wondering when the organisers of the campaign against the T shirt will turn their attention to the Auckland War Memorial Museum. On its second floor, in a room dedicated to the Second World War, Auckland's museum displays two of the most offensive objects of all time - Hitler's swastika flag, and his demented book Mein Kampf. Both objects help the museum tell the story of World War Two.

The shirt, which was produced to promote the heavy metal band Cradle of Filth and shows a nun masturbating as well as the slogan JESUS IS A CUNT, was banned from New Zealand in 2008. Canterbury museum's curators got special permission to show it - in a secluded, adults-only room - as part of an exhibition called T Shirts Unfolding. The museum wants its visitors to think about the limits to freedom of speech, and about the functions of censorship. The YMCA and co argue that the T shirt is offensive, and that museums should not display offensive objects.

I've been wondering when the organisers of the campaign against the T shirt will turn their attention to the Auckland War Memorial Museum. On its second floor, in a room dedicated to the Second World War, Auckland's museum displays two of the most offensive objects of all time - Hitler's swastika flag, and his demented book Mein Kampf. Both objects help the museum tell the story of World War Two.

Museums use objects to tell true stories about society and its past. A museum doesn’t necessarily endorse the messages encoded in the objects it displays, any more than a historian necessarily endorses the events and people he or she describes in an article or book.

The T shirt is helping Canterbury museum tell a story about street art, and about censorship. Canterbury museum isn’t endorsing the meaning of the shirt any more than Auckland museum endorses Nazism by displaying a swastika.

I haven’t seen the show in Christchurch, but I’d argue that state censorship is a subject that is worthy of coverage in our museums.

New Zealand has had a long history of state censorship of culture and of political speech. A hundred years ago Auckland cops were hunting down copies of Defoe’s Moll Flanders, on the grounds that it corrupted the public, and putting the book’s distributors in court. For decades anyone who published Marx risked time behind bars. In the 1920s Jean Devanny’s feminist novel The Butcher Shop became a bestseller and was promptly banned as offensive. During its confrontation with New Zealand's militant unions in 1951 the National government used emergency legislation to ban the leader of the opposition from radio airwaves. Right up until the 1990s, Maori sculptures displayed in museums or other public places were attacked with axes because the genitalia they showed upset religious conservatives.

We need to be aware of this historical context when we debate censorship and related issues, like state surveillance, today. I’m pleased that the Auckland museum’s permanent display on World War Two includes a section on the censorship laws introduced by the wartime Labour government, and shows a copy of an anti-war newspaper that Labour banned.

Many of the critics of Canterbury museum have argued that 'the community', that ubiquitous but mysterious entity, should be charged with deciding what New Zealand's museums exhibit. If an object is offensive to part of the community, then the object should, they suggest, serve a life sentence in a museum storage room.

But almost every object in a museum is likely to be offensive to someone, if that someone has mistaken exhibition for endorsement. Besides its swastika flag and commie newspaper, the Auckland museum displays artefacts from dozens of religions and relics from a series of wars.

On the museum's ground floor, for instance, masks and drums associated with Papuan religious rites rest a short walk from a massive and austere sculpture of Kave, a goddess from Nuku'oro atoll, a carving of the Madonna and child by an early Maori convert to Catholicism, and a Samoan-language Bible published by a Protestant church. Relics of the religions of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt advertise their creeds upstairs. In the room of the museum devoted to the New Zealand Wars, the Union Jack and the banners of Maori nationalist movements confront each other, as speakers play recordings of bugle calls and haka.

We can only appreciate myriad and contradictory exhibits like these if we accept that a museum is a space where different aspects of and ideas about the past are allowed to manifest themselves, and where visitors, rather than curators, have the responsibility for forming final interpretations.

When I worked at the Auckland museum the institution mounted a major show about Charles Darwin’s life and work. Darwin offended the religious views of some visitors. I remember, as well, the way that some veterans of the Vietnam War were offended by the museum’s coverage of that conflict. Those vets didn’t like the museum mentioning that the war had created considerable public debate and protest in New Zealand.

They may have been offended, and their views may have been shared by hundreds or thousands of other Aucklanders, but neither the religious folks who objected to Darwin nor the Vietnam veterans who objected to references to anti-war protests should have had the right to intervene and alter or shut down the museum’s displays. A museum’s duty is to the truth, and the truth about the past is complex, and polemicists speaking on behalf of a nebulous community have too little patience with complexity.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

But almost every object in a museum is likely to be offensive to someone, if that someone has mistaken exhibition for endorsement. Besides its swastika flag and commie newspaper, the Auckland museum displays artefacts from dozens of religions and relics from a series of wars.

On the museum's ground floor, for instance, masks and drums associated with Papuan religious rites rest a short walk from a massive and austere sculpture of Kave, a goddess from Nuku'oro atoll, a carving of the Madonna and child by an early Maori convert to Catholicism, and a Samoan-language Bible published by a Protestant church. Relics of the religions of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt advertise their creeds upstairs. In the room of the museum devoted to the New Zealand Wars, the Union Jack and the banners of Maori nationalist movements confront each other, as speakers play recordings of bugle calls and haka.

We can only appreciate myriad and contradictory exhibits like these if we accept that a museum is a space where different aspects of and ideas about the past are allowed to manifest themselves, and where visitors, rather than curators, have the responsibility for forming final interpretations.

When I worked at the Auckland museum the institution mounted a major show about Charles Darwin’s life and work. Darwin offended the religious views of some visitors. I remember, as well, the way that some veterans of the Vietnam War were offended by the museum’s coverage of that conflict. Those vets didn’t like the museum mentioning that the war had created considerable public debate and protest in New Zealand.

They may have been offended, and their views may have been shared by hundreds or thousands of other Aucklanders, but neither the religious folks who objected to Darwin nor the Vietnam veterans who objected to references to anti-war protests should have had the right to intervene and alter or shut down the museum’s displays. A museum’s duty is to the truth, and the truth about the past is complex, and polemicists speaking on behalf of a nebulous community have too little patience with complexity.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Public intellectuals, and other enemies of elitism

[In the aftermath of the debate about Eleanor Catton's criticisms of the Key government, the Christchurch Press has published a long and thoughtful article by Philip Matthews about public intellectuals and their place in New Zealand society. When he was researching his article, Matthews sent a short questionnaire to high-profile intellectuals like Nicky Hager and Jane Kelsey, as well as to dimmer lights like myself. Matthews has quoted a few of my responses in his article, but here they are in full.]

Do you consider yourself a public intellectual? I am a public intellectual because I do intellectual work that I try to relate to public issues. I research and write about the history of culture and ideas, but I don't want my research to be of merely historical interest. If I study New Zealand's nineteenth century, it's partly because I think that the events of that time, like the attempts of New Zealand to build a Pacific empire and the wars between Pakeha and Maori, are of relevance to the twenty-first century. In the same way, if I write about a great cultural figure of the past like George Orwell, it's because I think that figure has something to tell us today.

What does the role involve?

I admire many public intellectuals who have worked inside New Zealand's universities and museums, like the late Judith Binney and the late Roger Neich, but I also revere men and women like RAK Mason, Hone Tuwhare, and Elsie Locke, who worked for long periods in blue collar jobs, organised study groups inside their workplaces, gave lectures in trade union and community halls, and wrote important things about New Zealand society and its history during their free time. These working class public intellectuals believed that in a democratic society every citizen should take an interest in and contribute to intellectual debate. I agree with them. As the great Tongan public intellectual Futa Helu said, a democratic society is a society where everyone minds everyone else's business.

What are the risks of the public role?

The public intellectual risks being misunderstood by both intellectuals and the public. Intellectuals who are content to work within their chosen fields, without relating their research and writing to contemporary issues and debates, can sometimes consider public intellectuals a little vulgar, because of the way we try to popularise ideas and offer opinions about political issues. On the other hand, members of the public can perceive an intellectual who jumps into a public debate as some sort of elitist, who thinks his or her opinion is automatically more valid than those of ordinary mortals.

In some ways both of these responses are understandable, even if mistaken. Specialised scholarship is very important - without it, we would not have the facts and theories that are raw material for informed discussion of our world. And the Kiwi suspicion of intellectuals is often related to an egalitarian irreverence - a refusal to consider that qualifications or wealth or bloodline makes one person's opinion automatically better than another's - that is preferable to any form of snobbery.

I'd like to convince anti-intellectual Kiwis that public intellectuals are the enemies of elitism, rather than its exponents. Public intellectuals want to storm the palisades that separate intellectuals from the rest of society, and spread knowledge and debate. The way to defeat intellectual elitism is to create more public intellectuals and more public intellectual debate.

It is unfortunate that Eleanor Catton has been condemned by some commentators as an elitist, because her own words show that she believes in the wide dissemination of knowledge and the democratisation of intellectual discussion. In an article published last year, for example, Catton celebrated public libraries as places where New Zealanders could, regardless of their class background or educational qualifications, encounter ideas and develop their understanding of the world. Catton called for New Zealand governments to build many new public libraries; an elitist would never make such a demand.

Do you feel NZ supports its public intellectuals? Do our universities and media encourage them?

In New Zealand and elsewhere, intellectuals have to steer a course between marginalisation and cooption. New Zealand intellectuals know all about marginalisation. Censorship was widespread in New Zealand until the 1960s, with classics like Defoe's Moll Flanders as well as works of contemporary literature like Jean Devanny's bestselling novel The Butcher's Shop being targeted by the cops and courts. Our writers and artists were sometimes treated brutally, because of their failure to conform with cultural and mental mores. Frank Sargeson was prosecuted and sent to internal exile in the King Country; Janet Frame was almost lobotomised; Ian Hamilton was thrown into prison for years.

The recent experiences of Nicky Hager and Catton show that New Zealand intellectuals can still suffer excoriation by the media and the government, and even persecution by the police. But intellectuals also face the danger of cooption. A desire to maintain access to universities and funding agencies can tempt us to pull our punches. The Key regime has been more or less at war with intellectuals, but the Clark government's relatively sympathetic attitude to the arts and to universities sometimes seemed to insulate it from criticism it deserved.

I remember helping, as a member of an anti-war group, to organise a protest outside a meeting that Clark held with Auckland's art community in the city's main public gallery. It was a month or so after 9/11, and New Zealand troops were in Afghanistan, acting as spotters for George Bush's air force as it carried out an extraordinarily heavy and reckless bombing campaign - a campaign that has since been estimated to have killed five thousand civilians. My fellow anti-war activists and I found little enthusiasm for our placards and leaflets from the painters, art teachers, and curators who had come to see Clark: they were preoccupied with thanking her for the additional financial assistance she was giving the arts sector. Public intellectuals must guard against that sort of cooption.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Saturday, February 14, 2015

John Macmillan Brown's return from exile, and other fantasies

[Summer is the time of the year when I invent over-ambitious and sometimes absurd projects, and burden friends, editors, and publishers with my fantasies.

I sent this e mail to Paul Janman recently. I don't think he has time to take on the project, and I don't have the time or the expertise to develop the idea myself. I thought I'd post my e mail to Paul here, though, in case it finds a reader who is equipped with the time, expertise, and enthusiasm to retrieve John Macmillan Brown's vast and strange novels from exile in the library of obscurity...]

Hi Paul,

John Macmillan Brown was educationalist, an explicator of Shakespeare, and a scholar - a sometimes wayward scholar, it must be said - of the Pacific, who is perhaps best remembered today for being the grandfather of James K Baxter. In the first years of the twentieth century Brown published, under the pseudonym of Godfrey Sweven, two massive novels - Riallaro, the archipelago of exiles, and Limanora, the island of progress - that were intended as satires on religion and superstition and as arguments for atheism, rationalism, and science.

Influenced by Gulliver's Travels and - perhaps - by HG Wells, Brown sends the narrator of his books on a journey to an obscure region of the Pacific, where a series of bizarre societies have evolved on a series of almost perfectly isolated islands. Some of these societies are rustic and fierce; others are highly enlightened, and fitted out with supermodern technology. Readers are invited to draw conclusions about the connection between material progress and rationalism.

I sent this e mail to Paul Janman recently. I don't think he has time to take on the project, and I don't have the time or the expertise to develop the idea myself. I thought I'd post my e mail to Paul here, though, in case it finds a reader who is equipped with the time, expertise, and enthusiasm to retrieve John Macmillan Brown's vast and strange novels from exile in the library of obscurity...]

Hi Paul,

John Macmillan Brown was educationalist, an explicator of Shakespeare, and a scholar - a sometimes wayward scholar, it must be said - of the Pacific, who is perhaps best remembered today for being the grandfather of James K Baxter. In the first years of the twentieth century Brown published, under the pseudonym of Godfrey Sweven, two massive novels - Riallaro, the archipelago of exiles, and Limanora, the island of progress - that were intended as satires on religion and superstition and as arguments for atheism, rationalism, and science.

Influenced by Gulliver's Travels and - perhaps - by HG Wells, Brown sends the narrator of his books on a journey to an obscure region of the Pacific, where a series of bizarre societies have evolved on a series of almost perfectly isolated islands. Some of these societies are rustic and fierce; others are highly enlightened, and fitted out with supermodern technology. Readers are invited to draw conclusions about the connection between material progress and rationalism.

Brown's novels are nearly plotless, and consist mostly of extremely detailed descriptions of odd buildings, machines, and ideas. Because of their lack of action and teeming details, they are often dull to read.

But the images which Brown cumbersomely assembles are often original and strange. Arguably, they express subconscious obsessions and urges that are at odds with the author's rather sterile rationalism.

Let me offer an example. In a city that Brown's narrator visits, old-fashioned religion has been replaced by a sort of theatre, in which humans can watch film-like projections that give them the same ecstatic feeling that the worship of gods might once have provided. Brown's strange theater seems to me to express a longing for religious rapture, as much as a freedom from it.

Brown's books can be seen as pioneering works of science fiction, and they also look forward to some of the work of the surrealists. It is extraordinary that a New Zealander could produce such material a century ago.

But the images which Brown cumbersomely assembles are often original and strange. Arguably, they express subconscious obsessions and urges that are at odds with the author's rather sterile rationalism.

Let me offer an example. In a city that Brown's narrator visits, old-fashioned religion has been replaced by a sort of theatre, in which humans can watch film-like projections that give them the same ecstatic feeling that the worship of gods might once have provided. Brown's strange theater seems to me to express a longing for religious rapture, as much as a freedom from it.

Brown's books can be seen as pioneering works of science fiction, and they also look forward to some of the work of the surrealists. It is extraordinary that a New Zealander could produce such material a century ago.

I was imagining that you might be able to 'translate' Brown by mapping and visualising his vast and weird fictional world. Using your skills as a film maker and editor, you could shuck off those endless passages of minute description, and instead give us Brown's imaginings in hyperlinks and images. I'm thinking of a very particular, very interactive, and probably very original, type of e book: an island where visitors could lose their way...

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Sunday, February 08, 2015

Wednesday, February 04, 2015

Expensive Movements - and expensive photographs

Last December Brett Phibbs and Ioana Gordon-Smith both visited Pukekohe, which has the well-deserved reputation of being New Zealand's most redneck town.

In a paddock outside Pukekohe Phibbs, who is the chief photographer for the New Zealand Herald, took a series of shots of Polynesian workers while they brought in a harvest of onions. In a gallery near the centre of town Gordon-Smith, a curator and art critic, set up an exhibition called Making Visible, in which a group of artists emphasised, with a mixture of exasperation, anger, and humour, the contribution that workers from the Pacific Islands have made to New Zealand's economy and culture.

Phibbs' photographs were published in the Herald, and seen by many thousands of Kiwis. The exhibition that Gordon-Smith curated was viewed by a far smaller number of people, some of whom walked out of the gallery when they were confronted by images of Pacific Islanders driving forklifts or lying in Aotea Square.

Over at the online arts journal EyeContact, I've contrasted the photographs that Phibbs took at Pukekohe with some of the art that Gordon-Smith brought together in the town's gallery, and asked what Phibbs' images tell us about the way New Zealand sees migrant workers and Pacific Islanders. I've argued that Salome Tanuvasa's two screen video work Expensive Movements, which was shot at a brewery on Auckland's Great South Road and a hotel somewhere in the east of the city, can be seen as an implicit reply to Phibbs' photographs.

Unfortunately, the New Zealand has refused to let EyeContact reproduce Brett Phibbs' photographs without paying an unreasonably high fee. The paper's stance is disappointing, because New Zealand's galleries and museums have always allowed EyeContact to reproduce images of the works they hold for free. I'm hoping that Brett Phibbs will respond to my comments on his work by posting the photographs he took at Pukekohe online, so that everyone can see them.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]