Marching on the frontier

[This post started as an e mail to genealogist and military historian Christine Liava'a, who has been very generous in helping me with my research into blackbirding.]

Dear Christine,

I wanted to apologise for leaping out of my seat and running away from your talk about the Pacific front of World War One last Tuesday at the Papatoetoe library. I hadn't been offended by the old photographs and maps you'd been powerpointing, or by your discussions of warships and digging works and influenza. I simply needed to restrain my oldest son, who had decided, against the evidence offered by his mother, that he was a blue racing car, and that the carpark outside the library was his racing track.

Before my departure I was fascinated by your photograph of the Fijian members of the King's Royal Rifles. As I looked at the earnest and very white faces of the Fijian troops, I remembered the surprise I felt as a kid, when I flicked through a book about the history of test cricket and discovered a set of photographs of the teams the West Indies sent to England in the 1920s and '30s. Instead of the ancestors of mighty Windies players of the '80s, like Viv Richards and Mike Holding, the photographs were full of tall, stern Anglo-Saxons with white ties and thin moustaches. Like cricket, war was obviously considered a white man's sport by administrators of Britain's empire.

You noted how indigenous Fijians were carefully excluded from the King's Rifles, even though many of them were keen to fight the Kaiser. When you mentioned the tests that white Fijians had to pass before they could serve, though, I wondered whether they too might have been victims of imperial prejudices. When recruiters ran measuring tape over the men's chests and checked their height, were they guided by the belief that the inhabitants of the tropical Pacific, whether black or white or somewhere in between, were all susceptible to frailties uncommon in the colder parts of the world?

Until the middle of the twentieth century, many Europeans and Australasian whites were convinced that the heat and humidity of the tropics made their inhabitants decadent and sickly. For decades, Australian politicians and planners debated how they might settle the northern part of their continent without creating a race of 'degenerate whites'. New Zealand advocates of the annexation and colonisation of societies like Fiji and Samoa insisted that Kiwis who emigrated there should be helped to take, every five years or so, a long, restorative holiday in their cool mother country, so that their bodies and souls could be rid of tropical languor, lasciviousness, and depression. After German Samoans declined to resist New Zealand's invasion of their colony, Kiwi newspapers attributed their surrender to the effects of too many years of heat and humidity.

It is certainly true that, in the cooler parts of the British Empire, volunteers for World War One were not tested as stringently as the men from Fiji. Ronald Blythe has revealed that many of the men who fought for Britain on the Western front and in Gallipoli were slight and prone to fatigue, because of the poor diets they had suffered as children and young adults in the working class and rural districts of the mother country. I wonder how many of these men would have passed the test administered to the Fijians?

It seems, though, that a dozen members of the Fijian section of the Legion of Frontiersmen avoided the testing and drilling that were the lot of the colony's regular soldiers. You noted how, in August 1914, the Frontiersmen were welcomed onto one of the ships New Zealand sent to conquer Samoa, and you powerpointed a photograph taken shortly after the 'liberation' of Apia, in which they pose with a captured German flag.

Although it was founded in 1905 by a Boer War veteran who believed that the British Empire needed a massive, disciplined, and battle-ready paramilitary force, the Legion struggled to convince generals and politicians of its usefulness. Its direct involvement in the expedition to Samoa seems, then, surprising.

Last Tuesday you joked about not understanding the purpose of the Legion. I agree that the group has seemed, for a long time, quixotic. I consider it one of a panoply of organisations - paramilitary forces, mystical orders, thwarted political parties, lobby groups - that were created early in the twentieth century to celebrate and defend the British Empire. By the beginning of the century, the empire was both mighty and imperilled. It covered more than a fifth of the world's land surface, but the ambitions of rivals like Germany and America and class and racial conflict had made its supporters uneasy. Novelists and newspaper polemicists had begun to imagine German invasions and conquests of Britain, and revolutions that replaced the Union Jack with the red flag of socialism.

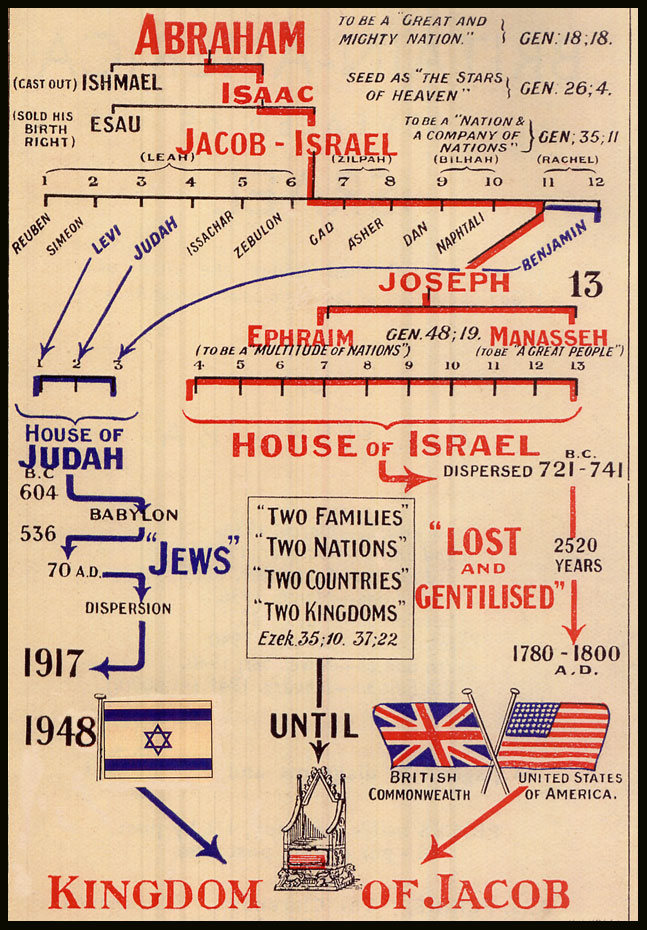

British Israelites and neo-Arthurian mystics looked to the Bible and to pseudo-archaeology for reassurance that British pre-eminence was divinely ordained and permanent; the Frontiersmen believed that God's will might have to be enforced with bayonet charges.

The word 'Frontiersmen' must have resonated with New Zealanders. As Jock Phillips and James Belich have shown, Kiwis liked to contrast their improvisational, often rough lifestyles with the supposedly effete ways of Britons. The over-elaborate vocabularies and overstuffed suitcases of new arrivals from the old country were ridiculed by newspapers. Like the anxious Britons who founded the Legion of Frontiersmen, many Kiwis believed that the true spirit of the empire could be found on the edges of the British world. On the frontier of the empire, exposed to Antarctic storms and Maori raiding parties, New Zealanders had been forced to preserve the manly qualities that had been lost in metropolises like London and Manchester and Calcutta.

It seems to me that the invasion of Samoa might almost be the high point in the military history of the Legion. The thousands of Frontiersmen spread around the empire appear to have done a lot of flag-waving, marching, and saluting, but very little fighting, unless they also belonged to the regular armed forces. The Frontiersmen's role in the invasion of Samoa seems almost unparalleled in the organisation's history.

In the years between the wars the Legion seems to have stayed busy, and even to have impressed the odd observer. In an article written at the end of the 1930s for the People's Voice, the communist poet and polemicist Gordon Watson included the Legion in a list of organisations that were planning to use the coming war with Hitler as an excuse to impose a right-wing dictatorship on New Zealand.

Watson's claim might not have been as absurd as it looks. In 1930s Britain Frontiersmen were often mistaken for Oswald Moseley's British Union of Fascists, because of their dark uniforms, angry anti-communism, and penchant for marching. During a strike on the Vancouver waterfront in 1935, Frontiersmen as well as members of local fascist parties were recruited as special policemen and encouraged to charge at picket lines. A couple of years earlier, during the most depressed period of the Great Depression, an anti-communist and anti-democratic movement spread briefly but spectacularly from Hawkes Bay through the rest of the country. Is it a coincidence that this movement was called the New Zealand Legion?

Like the empire it wanted to defend, the Legion has declined and almost disappeared in the decades since the Second World War. You mentioned finding a few middle-aged Frontiersmen working as ushers at some public event in South Auckland; the South Taranaki Star reports that even this sort of activity is nowadays too difficult for the Legion's four elderly members in New Plymouth, who have decided to retire.

I wanted to return to 1914, though, and ask: is it possible that the Frontiersmen were allowed to seek glory in Samoa because of the intervention of New Zealand's Prime Minister? William Massey grew up in northern Ireland, a place where British had always been embattled, and as a fervent British Israelite he considered World War One a struggle for the survival of God's chosen people. The commanders of New Zealand's professional army may well have been suspicious of the Legion's part-time soldiers, but Massey would have admired the group's ideology. Might he have considered that, in the midst of a holy war, faith and patriotism would be more important than training and equipment? Perhaps a letter somewhere in Massey's archive can answer these questions.

'Ofa atu,

Scott

Dear Christine,

I wanted to apologise for leaping out of my seat and running away from your talk about the Pacific front of World War One last Tuesday at the Papatoetoe library. I hadn't been offended by the old photographs and maps you'd been powerpointing, or by your discussions of warships and digging works and influenza. I simply needed to restrain my oldest son, who had decided, against the evidence offered by his mother, that he was a blue racing car, and that the carpark outside the library was his racing track.

Before my departure I was fascinated by your photograph of the Fijian members of the King's Royal Rifles. As I looked at the earnest and very white faces of the Fijian troops, I remembered the surprise I felt as a kid, when I flicked through a book about the history of test cricket and discovered a set of photographs of the teams the West Indies sent to England in the 1920s and '30s. Instead of the ancestors of mighty Windies players of the '80s, like Viv Richards and Mike Holding, the photographs were full of tall, stern Anglo-Saxons with white ties and thin moustaches. Like cricket, war was obviously considered a white man's sport by administrators of Britain's empire.

You noted how indigenous Fijians were carefully excluded from the King's Rifles, even though many of them were keen to fight the Kaiser. When you mentioned the tests that white Fijians had to pass before they could serve, though, I wondered whether they too might have been victims of imperial prejudices. When recruiters ran measuring tape over the men's chests and checked their height, were they guided by the belief that the inhabitants of the tropical Pacific, whether black or white or somewhere in between, were all susceptible to frailties uncommon in the colder parts of the world?

Until the middle of the twentieth century, many Europeans and Australasian whites were convinced that the heat and humidity of the tropics made their inhabitants decadent and sickly. For decades, Australian politicians and planners debated how they might settle the northern part of their continent without creating a race of 'degenerate whites'. New Zealand advocates of the annexation and colonisation of societies like Fiji and Samoa insisted that Kiwis who emigrated there should be helped to take, every five years or so, a long, restorative holiday in their cool mother country, so that their bodies and souls could be rid of tropical languor, lasciviousness, and depression. After German Samoans declined to resist New Zealand's invasion of their colony, Kiwi newspapers attributed their surrender to the effects of too many years of heat and humidity.

It is certainly true that, in the cooler parts of the British Empire, volunteers for World War One were not tested as stringently as the men from Fiji. Ronald Blythe has revealed that many of the men who fought for Britain on the Western front and in Gallipoli were slight and prone to fatigue, because of the poor diets they had suffered as children and young adults in the working class and rural districts of the mother country. I wonder how many of these men would have passed the test administered to the Fijians?

It seems, though, that a dozen members of the Fijian section of the Legion of Frontiersmen avoided the testing and drilling that were the lot of the colony's regular soldiers. You noted how, in August 1914, the Frontiersmen were welcomed onto one of the ships New Zealand sent to conquer Samoa, and you powerpointed a photograph taken shortly after the 'liberation' of Apia, in which they pose with a captured German flag.

Although it was founded in 1905 by a Boer War veteran who believed that the British Empire needed a massive, disciplined, and battle-ready paramilitary force, the Legion struggled to convince generals and politicians of its usefulness. Its direct involvement in the expedition to Samoa seems, then, surprising.

Last Tuesday you joked about not understanding the purpose of the Legion. I agree that the group has seemed, for a long time, quixotic. I consider it one of a panoply of organisations - paramilitary forces, mystical orders, thwarted political parties, lobby groups - that were created early in the twentieth century to celebrate and defend the British Empire. By the beginning of the century, the empire was both mighty and imperilled. It covered more than a fifth of the world's land surface, but the ambitions of rivals like Germany and America and class and racial conflict had made its supporters uneasy. Novelists and newspaper polemicists had begun to imagine German invasions and conquests of Britain, and revolutions that replaced the Union Jack with the red flag of socialism.

British Israelites and neo-Arthurian mystics looked to the Bible and to pseudo-archaeology for reassurance that British pre-eminence was divinely ordained and permanent; the Frontiersmen believed that God's will might have to be enforced with bayonet charges.

The word 'Frontiersmen' must have resonated with New Zealanders. As Jock Phillips and James Belich have shown, Kiwis liked to contrast their improvisational, often rough lifestyles with the supposedly effete ways of Britons. The over-elaborate vocabularies and overstuffed suitcases of new arrivals from the old country were ridiculed by newspapers. Like the anxious Britons who founded the Legion of Frontiersmen, many Kiwis believed that the true spirit of the empire could be found on the edges of the British world. On the frontier of the empire, exposed to Antarctic storms and Maori raiding parties, New Zealanders had been forced to preserve the manly qualities that had been lost in metropolises like London and Manchester and Calcutta.

It seems to me that the invasion of Samoa might almost be the high point in the military history of the Legion. The thousands of Frontiersmen spread around the empire appear to have done a lot of flag-waving, marching, and saluting, but very little fighting, unless they also belonged to the regular armed forces. The Frontiersmen's role in the invasion of Samoa seems almost unparalleled in the organisation's history.

In the years between the wars the Legion seems to have stayed busy, and even to have impressed the odd observer. In an article written at the end of the 1930s for the People's Voice, the communist poet and polemicist Gordon Watson included the Legion in a list of organisations that were planning to use the coming war with Hitler as an excuse to impose a right-wing dictatorship on New Zealand.

Watson's claim might not have been as absurd as it looks. In 1930s Britain Frontiersmen were often mistaken for Oswald Moseley's British Union of Fascists, because of their dark uniforms, angry anti-communism, and penchant for marching. During a strike on the Vancouver waterfront in 1935, Frontiersmen as well as members of local fascist parties were recruited as special policemen and encouraged to charge at picket lines. A couple of years earlier, during the most depressed period of the Great Depression, an anti-communist and anti-democratic movement spread briefly but spectacularly from Hawkes Bay through the rest of the country. Is it a coincidence that this movement was called the New Zealand Legion?

Like the empire it wanted to defend, the Legion has declined and almost disappeared in the decades since the Second World War. You mentioned finding a few middle-aged Frontiersmen working as ushers at some public event in South Auckland; the South Taranaki Star reports that even this sort of activity is nowadays too difficult for the Legion's four elderly members in New Plymouth, who have decided to retire.

I wanted to return to 1914, though, and ask: is it possible that the Frontiersmen were allowed to seek glory in Samoa because of the intervention of New Zealand's Prime Minister? William Massey grew up in northern Ireland, a place where British had always been embattled, and as a fervent British Israelite he considered World War One a struggle for the survival of God's chosen people. The commanders of New Zealand's professional army may well have been suspicious of the Legion's part-time soldiers, but Massey would have admired the group's ideology. Might he have considered that, in the midst of a holy war, faith and patriotism would be more important than training and equipment? Perhaps a letter somewhere in Massey's archive can answer these questions.

'Ofa atu,

Scott

5 Comments:

the legion raised several batallions in ww1 but did not control them. but did they really act as autonomous force in samoa or were their men dissolved into nz army?

Certainly, those Frontiersmen who remained at home during WW1 were eager to play their part in advancing Massey's Imoperial cause. In 1916 the country's police force prepared for a massive armed assault on a small and utterly remote Maori community in the depths of the Urewera. Its religious leader, Rua Kenana, had discouraged his followers from enlisting for the war, and had an earlier history of non-compliance with the settler government. The Bay of Plenty branch of the Legion of Frontiersmen offered to supply a 40-strong continent of mounted and armed volunteers to assist the police expedition that planned to arrest Rua. Police Commissioner John Cullen was clearly taken with this idea and recommended accepting the offer, but wiser heads apparently prevailed. Otherwise the death and injury toll from this disastrous and futile expedition might well have been even higher.

looks like an interesting report here

http://jacothenorth.net/blog/legion-of-frontiersmen/

Thanks for that info, Mark. According to the official website of the Kiwi Frontiersmen, a small number of Maori have been involved in the organisation over the years. I suppose not many were Tuhoe.

It is fascinating to reconsider New Zealand history in the light of the fact that, in the second half of the nineteenth and the early decades of the twentieth centuries, significant numbers of the country's Pakeha elite - businessmen, high-ranking soldiers, politicians - were members of secret or semi-secret societies motivated by mystical doctrines. We're so used - perhaps I should say I'm so used - to looking at Maori leaders like Rua Kenana, noting their use of mystical and millenarian ideas, and making a contrast with a more soberly secular Pakeha political leadership that we risk missing the very peculiar and decidedly eschatological doctrines that were dear to men like William Massey.

I got particularly interested in rogue British Israelite AH Dallimore, who constructed a large church in Otahuhu, during my research into the Great South Road:

http://healingandrevival.com/BioAHDallimore.htm

Post a Comment

<< Home