Who speaks for Ruatoria?

Ngati Dread took a decade to research, and includes long, often unexpurgated interviews with numerous survivors of the violence of the '80s, as well as many pages lifted from court transcripts.

Steve Braunias read Ngati Dread, and was excited enough to celebrate it over at The Spinoff. Braunias did a long and fascinating interview with Gillies, commissioned a review of Ngati Dread by Talia Marshall, and ran an excerpt from the book's first volume.

As Braunias concedes in a new post at The Spinoff, though, not everyone shares his enthusiasm for Ngati Dread. In a series of messages to Braunias, the Ruatorian Kiri Dell questioned Gillies' probity and prose style, complaining that:

Clearly this whole thing lacks a concern about people and is a focus on book sales...This is not your story to tell, it is our story. These books are terribly written and the interview skills weak, bias and leading...Why do white people write about us? Ask yourself Angus, who are you serving by writing these books?

Braunias had commissioned a piece about twenty-first century Ruatoria, but its unnamed author got cold feet, explaining that:

I've seen a range of reactions from locals to the Angus interview, some negative but some less so. I'm not sure it's culturally insensitive - just basic human dignity insensitive and unethical, it's really no one else's story to tell, so if the community doesn't want to tell it, then leave it alone until they are ready to share it - or not.

Here's a comment that I left at The Spinoff:

According to the anonymous writer who withdrew a piece from The Spinoff, the story of the Rasta uprising of the 1980s should only be told when 'the community' of Ruatoria and surrounding areas is 'ready' to tell it. According to Kiri Dell, the Ruatoria community should be able to be able to tell its own story, 'in its own words' and from 'its own eyes'.

Both of these comments imply that the community of Ruatoria has a single perspective on the past, and a single way of talking about that past. Both commenters suggest that, simply because some inhabitants of the area disagree with what Angus Gillies has written in Ngati Dread, Gillies' book must be untruthful and his methods unethical.

What Ngati Dread and other accounts of the Rasta uprising of the 1980s surely show us, though, is that Ruatoria in particular and the East Coast in general are not communities whose people think alike, but rather sites of long-running conflict.

The Rasta uprising was a conflict inside Ngati Porou, as much as between Maori and Pakeha. As Angus Gillies notes in his interview with The Spinoff, the leader of the Rastafarians was killed by his own cousin.

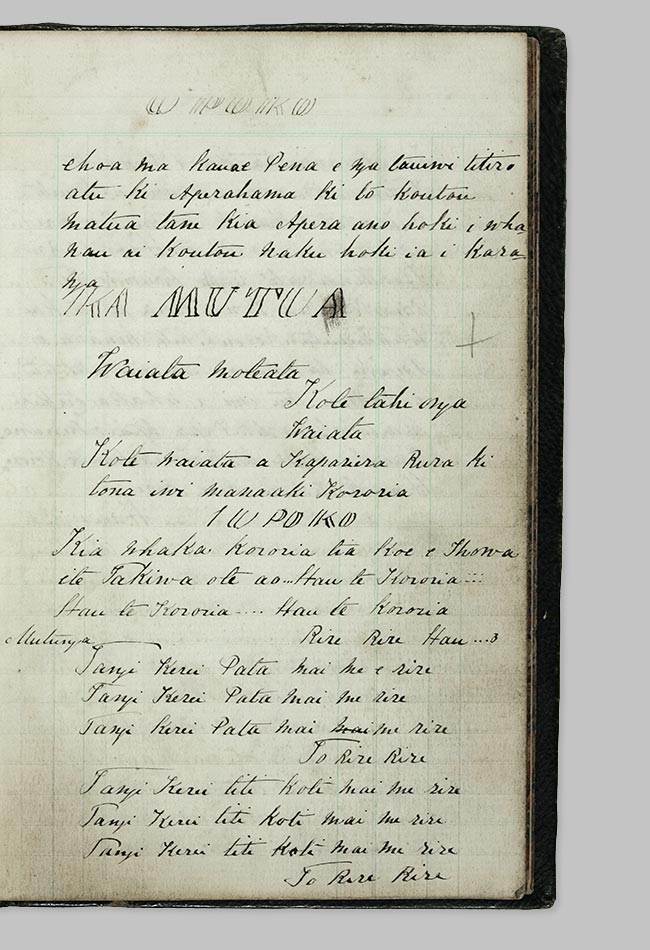

When they hailed Te Kooti as a prophet of their religion, the Rastas invoked the memory of the Ngati Porou civil war of 1865-66, which saw adherents of the anti-colonial Pai Marire faith defeated by a conservative faction of the iwi intent on making alliances with the colonial government and the British Empire. Te Kooti became identified with the Pai Marire rebels, and began his own war against Ngati Porou's conservatives after escaping from the Chatham Islands, where he had been imprisoned with other rebels.

In the twentieth century conservative leaders of Ngati Porou like Apirana Ngata had immense influence over government policy toward Maori. They worked to stymie new rebels against colonial authority, like Rua Kenana in the Ureweras. Only a decade ago Ngati Porou's leaders helped to weaken the pan-iwi movement against Labour's seabed and foreshore legislation by making a deal with the government.

The Rastafarian movement can be considered, in part, as a renewal of the nineteenth century revolts against Ngati Porou's leaders. It is significant that some of the mentors of the movement, like Sue Nikora, have been involved in the attempts of dissatisfied hapu to secede from Ngati Porou. In Potaka and around the East Cape, near the edges of Ngati Porou authority, rebellious hapu have over the last decade declared their independence not only from the iwi leadership but from the state of New Zealand. These rebels have made their own Treaty claims.

Given their place in a long and continuing history of conflict, is it really reasonable to expect that the events of the 1980s would be interpreted in a single way by the Ruatoria community? Do other communities with a history of conflict view and discuss their history without disagreement?

The list of fifty great books about Maori compiled for The Spinoff by Te Roopu Haututu included Redemption Songs, Judith Binney's epic biography of Te Kooti, and Michael King's famous account of the life of Princess Te Puea. But when Redemption Songs was published twenty years ago it was received with anger as well as acclaim, because Maori as well as Pakeha descendants of some of the victims of Te Kooti's military campaigns considered that Binney had been too sympathetic to her subject. And although King's portrait was admired by many supporters of the Kingitanga, some of the hapu of the lower Waikato were very upset by the historian's decision to take the side of Te Puea against their more conservative, pro-Crown ancestors.

It is not only in Maori communities that conflict over the interpretation of the past persists. I grew up in Franklin, down the road from the farms of the Crewe and Thomas families, and remember the bewilderment and anger that the murder of the Crewes and police frame-up of Arthur Alan Thomas caused in a small and conservative rural community.

Steve Braunias discusses the murders and their psychic effects in a chapter of his book Civilisation. I admired the chapter, and showed it to my mother. She liked it too, but another local disliked Braunias' tone and assertions. The different opinions of Braunias' text did not surprise me: Franklin is still divided by the Crewe killings, with different families favouring different theories about the event, and the families of the cops who framed Thomas still trying quixotically to rehabilitate their kin. None of the many books about the Crewe murders has been received with unanimity in Franklin.

If the rules that Kiri Dell and the anonymous would-be writer for The Spinoff suggest were adopted, then the writing of history would become impossible. No community speaks with one voice, and interprets its past in one way.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]