Grumpy bugger, gloomy bugger

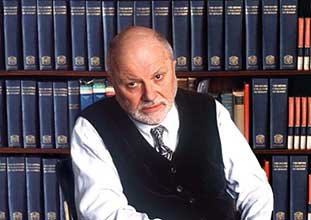

A friend of mine remembers talking to a student who had Geoffrey Hill as a tutor at some British university. 'If you have Hill as a tutor, you make damn sure you get your reading done and your essay in on time' the student said. 'I mean, just look at the covers of the guy's books. He looks like he's emerging from the Cave of Blood. You don't mess with a guy like that.'

Hill has for many years held the much-contested position of Grumpiest Living Writer in English: his books are grumpily recalcitrant, full of impenetrable allusions and capricious puns, and they lament the decline of Western civilisation and the unworthiness of today's youth with all the fervour of a retired sergeant-major's letters to The Times. Why, then, should we read the old bugger? Haven't we heard it all before, in rather more accessible form? Writing about Hill's new(ish) book of poems, Scenes from Comus, Colin Burrow admits that:

None of the delights offered by this volume comes easily...Hill will repeatedly make you reach for your dictionary ("Oh damn this pondus of splenetic pride!"), but he will always make looking something up worthwhile. In the lines "Sharp-shining berries bleb a thorn, as blood | beads on a finger", most people could probably see that "bleb" means "blister". The word isn't a piece of mannered obscurity: it's perfectly fitted by its sound to its place. There is music and beauty here.

What, though, is it about? The central focus of Scenes from Comus is the emergence and suppression of sense - both in the sense of "meaning" and in the sense of "sensuality". A few years ago Hill's verse was obsessively concerned with the corruption of the language by politicians and journalists. He could often seem too angry at the weakness of his readers to want to make much contact with them. During this period Hill experimented with a number of personae, from prophet to angry old man. This collection is mellower, and its main voice is of rueful, bruised sensuousness rather than of a prophet crying in the wilderness. In Scenes from Comus Hill recognises that reader and poet alike are trying to find beauty through their senses, and he gives the impression that the poet is fighting with rather than against his readers.

Or, as the similarly recalcitrant WS Graham once wrote:

I am trying to translate the English language

into English

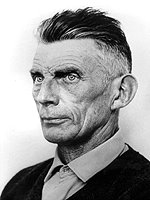

Samuel Beckett was famous for being not so much a grumpy as a gloomy bugger, but a new article by his old friend Edna O'Brien wants to present us with a different view of 'Sam the man'. According to O'Brien, the author of Waiting for Godot was a regular barfly:

Many people met Beckett and inevitably drank with him. It is true that he drank quite a lot and is almost certainly truer that he needed to drink, both to vivify a spirit that had "little talent for happiness" and to lessen the barrage of fellow imbibers.

O'Brien comments amusingly on Beckett's undiminished critical reputation:

It would not be unreasonable to suppose that he is now known on the moon, a region he once ruefully regarded as being the preserve of Albert Camus.

But it's rather difficult, finally, to see O'Brien's memories of Beckett as a refutation of his reputation as a gloomy old bugger:

Our last meeting was in the Pullman Hotel in Paris in 1989, a crowded venue in which he, tall and gaunt, seemed like a carved figure from some bygone civilisation, aloof from the frenzied surroundings. He asked if I agreed that the air in his arrondissement was very clean and very fresh. I couldn't in all honesty concur. The talk got around to the hereafter. I said I had a fine gravesite on an isolated island in the Shannon. After a short pause, it became clear that his remains were not bound for the cold mantled land. He told me how Donald McWhinnie had telephoned him from his deathbed, hoping for a word of wisdom.

"What did you tell him?"

"Not much," was the hapless reply.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home