Christopher Read is a Professor of Modern European History at the University of Warwick, and his

new life of Lenin is part of the Routledge Historical Biography Series that has already given us Ian Thatcher's study of Trotsky. The series aims to provide books that are both accessible and 'academically credible', and Read has certainly succeeded in doing this. His book is crisply written and clearly organised, and manages to cover Lenin's extraordinary life in only 300 pages without unreasonable simplification.

The modest length of Read's book means that he is unable to match the detail of the monumental, multi-volume studies of Lenin and Bolshevism put forth by scholars like Robert Service and EH Carr. Nor does he present us with new primary sources, in the manner of most biographies written since the opening of once-secret Soviet archives in the late 1980s. The strength of Read's book is the interpretation it brings to the key events of Lenin's life, and the new readings it suggests for key texts in the Lenin canon. Read's interpretation is dispensed lightly and unpolemically, but it is nonetheless original and interesting.

To understand the significance of Read's perspectives we need to remember the sorry story of the academic study of Lenin and the Bolshevik revolution. In the West, at least, there are four distinct periods in this story. The first period, which coincided roughly with the beginning of the Cold War, was dominated by anti-communists like Robert Conquest. These Cold Warriors tended to read all the deformities and absurdities of Stalin's Soviet Union into Lenin's writing, and into the practice of the Bolsheviks from 1903 onwards. 'Leninism' was presented as a system of tightly-integrated ideas that led logically and inevitably to the horrors of Stalinism.

In the late 1960s and the 1970s, the upsurge of radical politics in the West and the entrance of a new generation into academia generated a challenge to the perspective of the Cold Warriors. Younger, left-wing scholars in the humanities sought to retrieve Lenin from Stalin's shadow, and link his ideas to the revolutions and national liberation struggles unfolding in parts of Asia and Africa.

The exercise in revisionism was stalled by the rise of postmodernism in the academy of the 1980s. Under the guise of methodological radicalism, scholars captured by post-modernism actually reverted to some of the prejudices of curmudgeons like Conquest. By focusing on the linguistic surface of 'Leninist' texts, and on the 'discourse' of Bolshevik Russia, they lost a sense of the historical and social context of Lenin's ideas, and on what the Bolsheviks actually did with those ideas. Once again, 'Leninism' became a self-sufficient set of concepts that overdetermined any historical and social context it was inserted into.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, commentators throughout the West rushed to announce the triumph of capitalism and the 'end of history'. Not surprisingly, Lenin was consigned by these commentators to the dustbin of history, along with the state that identified itself with him right up til its dying day. In the first biography of Lenin to draw on newly-opened archives, Dmitri Volganokov presented his one-time hero as an arch-fiend who 'destroyed everything in Russia'. In

another book based on the new sources, Richard Pipes characterised Lenin as a 'heartless cynic' and a 'thoroughgoing misanthrope'.

Now, a decade and a half after 'triumph of capitalism', the US is in economic and military decline, the Middle East is gripped by chaos, and Latin America is beset by revolutionary turmoil. Understandably, then, a certain sobriety has descended upon some of those who danced on the grave of socialism. Today Francis Fukuyama is famous not for his proclamation of the end of history and the hegemony of the US but for criticisms of US foreign policy. Christopher Read's biography is part of a new turn in the study of Lenin and Bolshevism, a turn which perhaps corresponds somewhat with the new conditions we live in.

Throughout his book, Read is at pains to disagree with some of the more cartoonish claims made by the likes of Volganakov and Pipes. Discussing Lenin's desire to see the First World War turned into a revolutionary class war, Read insists that:

It should not...be inferred that Lenin in any way lauded violence and misery. Quite the opposite. His whole life had been devoted to abolishing misery and war. Marxism was the mechanism by which it could be done. Read points to Lenin's refusal to benefit financially and materially from his political power - we learn that he angrily refused offers to increase his very modest salary, and lived in a cramped four room flat in the Kremlin with his wife Krupskaya. Read absolves Lenin of repsonsibility for the cult of personality that become one of the many grotesqueries of the Soviet Union:

Only a few photos of Lenin existed. He hardly ever appeared on the propaganda posters of the day. In fact, when he heard that a woman named Valentina Pershikova had been imprisoned in Tsaritsyn for defacing one of the relatively infrequent portraits of him Lenin ordered her release saying 'Nobody should be arrested for defacing a picture'...He never promoted himself...he even had Gorky censured by the Politburo for being too glowing in his praise of Lenin...He also described Kamenev's proposal to collect and reprint Lenin's works as 'completely superfluous'...[when] Karl Radek mentioned to Lenin that he had been reading his writings of 1903, Lenin replied mockingly with a crafty smile: 'It's interesting to see how stupid we were then!'Read does not, however, try to 'rehabilitate' Lenin completely, and we can be thankful for this. All too often, Marxist portraits of Lenin have simply inverted the work of right-wingers, and found nothing but virtue in the man's life and works. To take such an approach means accepting the Cold Warriors' claim that Lenin's ideas and doings are essentially homogenous - all parts of a jigsaw that Stalin named 'Leninism'. Lenin's ouevre becomes a tablet handed down from on high, the self-sufficient and perfectly consistent thought of a God or Devil, rather than a record of the efforts of a real man to think through and act against the manifold obstacles his era put in the way of the struggle for the liberation of human beings from imperialism and barbarism.

For Read, Lenin was a man of contradictions. He was a mixture of the 'professor' and the 'politician', as happy in a library as on a stage, and these two halves did not always mix easily. Read's Lenin wanted to liberate the Russian people from Tsarism and war, but his commitment to a socialist model of development contradicted his desire to let loose the 'creativity of the masses'. In Read's view, the contradictory features of Lenin's thought gave the society he helped create contradictory features. Lenin's 'workers' state' ended up banning strikes and making trade unions subordinate to the Communist Party.

Read's presentation of Lenin's 'contradictions' seems a little simplistic, and his assessment of some of Lenin's policies seems to give too little attention to the tremendous damage done to the Soviet Union by the Civil War and the invasion of the country by sixteen states, including Britain and the United States. While clearly wrong, the Bolsheviks' closure of independent newspapers and repression of left-wing opponents seems less reproachful when we remember that their White opponents were massacring tens of thousands of Jews and planning the reintroduction of serfdom.

But the real strength of Read's interpretation of Lenin lies in the fresh readings it allows him to do of key 'Leninist' texts. His view of Lenin as a contradictory thinker enables him to discuss things that other, more ideologically blinkered scholars have passed over in silence. A case in point is Read's consideration of

What Is To Be Done?, a work regarded by most commentators of the left and the right as the foundation stone of 'Leninism'.

What Is To Be Done? has been seen as a textbook for a distinctively 'Leninist' organisation - a small, secretive 'vanguard party' designed to bring revolutionary consciousness to the working class from the 'outside' and leading the socialist revolution. Read, though, sees things differently:

Does What Is To Be Done? constitute a blueprint for Bolshevism?...Not necessarily. On the one hand, Lenin quotes many mainstream Social Democrats in support of his position, including Karl Kautsky...Similarly, Lenin points to existing forms of educated, conscious, permanent, stable leadership in the form of Liebknecht and Bebel and the leaders of the German Social Democratic Party. Surely these points indicate that Lenin was being less radical than appeared later to be the case?

...Lenin's other great model for the Party leadership comes from the early period of Russia's own populist revolutionary movement...Once again, his own youthful populism and admiration of the early populists were in evidence.It is notable that

similar points are made, in a great deal more detail, in Lars Lih's

new nine hundred page study of

What Is To Be Done? Lenin is famous for his refusal to give political support to the provisional government installed in Russia after the February 1917 revolution, and for his insistence on the need for a violent revolution to overthrow capitalism. Read complicates this picture a little by highlighting a couple of documents which suggest a more flexible attitude. In an article called

'On Compromises' written a couple of months before the October revolution, Lenin talks of the possibility of a new government being formed by the 'petty bourgeois' Social Revolutionary and Menshevik parties, and advocates support for such a government, on the grounds that it would create a democratic breathing space in which the Bolsheviks could consolidate their power in the Soviets.

Read is also able to highlight interesting contradictions in Lenin's attitude to the state. Lenin considered

State and Revolution his most important work, and the book's call for the destruction of the capitalist state and its replacement with a revolutionary workers' state built on direct democracy has become Marxist orthodoxy, along with the assumption that the Bolsheviks created such a state after October 1917. Read, however, points out that in

one of his last articles Lenin said that 'our state apparatus is to a considerable extent a survival of the past and has undergone hardly any serious change'. Where does this admission leave the Marxist groups which have criticised Venezuela's Bolivarian revolution, on the grounds that it has not 'smashed the old state' in that country? At the very least, Lenin's words in 1923 should give us pause for thought.

At the end of his book, Read tentatively links his research to the work of a number of other scholars who are trying to examine what Lars Lih calls 'the historical Lenin'. For my money, at least, this 'historical Lenin' looks far more relevant to the twenty-first century than the caricatures drawn by the rival camps of the Cold War.

Forty years ago, Louis Althusser urged us to recognise that the works of Marx were not a sacred stone tablet, but a complex, contradictory, and incomplete inheritance whose insights Marxist scholars and the socialist movement had to critically and creatively extend. Christopher Read's new biography of Lenin helps us to understand that the same lesson applies to the rich inheritance Lenin left behind.

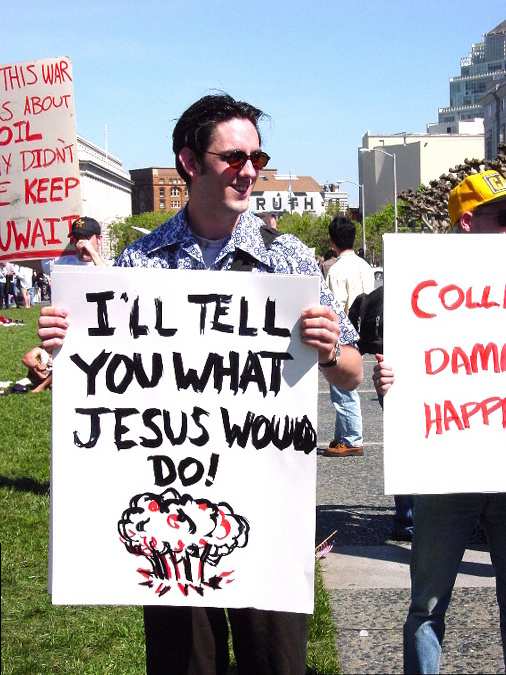

Robert Fisk: Mystery of Israel's secret uranium bomb

Robert Fisk: Mystery of Israel's secret uranium bomb

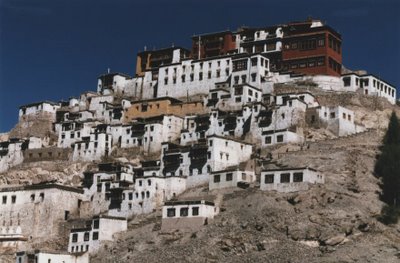

'Born in Cloppenburg in 1941, the artist

'Born in Cloppenburg in 1941, the artist