[

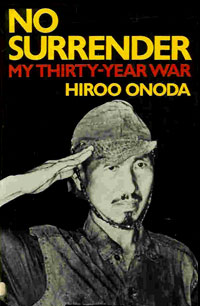

[Several months ago I was asked to contribute to a proposed book about the history of the British left since 1956. My contribution was to take the form of a very short abstract, which could be expanded into a chapter if the book were accepted by a publisher. I suppose that I could have written something about my mate EP Thompson and the 'New Left' movement he helped to create in the late 1950s and early '60s, but I've just published a book which dwells on that subject, and I worried that I'd end up repeating what I'd already written there.

I decided to write something about Irish Republicanism and its impact on the British left during the Troubles. It might reasonably be asked what possible insights a thirty-something Kiwi who has never visited Ireland could have about such a subject. I certainly agree that it would be quixotic for me to try to recapitulate the story of the Troubles in great detail, or to analyse in definitive detail the effects of the Good Friday Agreement from the other side of the world.

I'd like to think, though, that someone who examines a very complicated and parochial society and political scene from a great distance and an unusual angle can occasionally see something which eludes locals. My friend Carey Davies, who

admits to being a Yorkshire national chauvinist, argues that one of the best things about living in New Zealand is the odd angle this place provides for observers of northern hemisphere societies.

In the

introduction to my book on Thompson, I argued that I might have been able to see some of his preoccupations - his identification with obscure and provincial cultures and societies, for example, and his sympathy for peoples fighting the enclosure of their land by capitalist 'modernisers' - with a certain clarity, because of my residence in the South Pacific. I'm sure there are things that I missed because of my location, things that Carey and others northerners can pick up.

I'd like to think that the

oft-remarked parallels between New Zealand and Irish history, and between the Maori and Irish fights against imperialism, offer a potential way into Irish Republicanism for a Kiwi.

It's impossible to read about the decision of the Irish Republicans to set up a parrallel, anti-colonial state in 1919 and not think about the

separate parliaments, police, and dog tax collectors of the Kingitanga movement. The arguments of Irish Republicans about whether or not to abstain from imperialist institutions like Stormont and Westminster resemble the difficult debates within Tainui over whether or not to recognise Pakeha local and national governments in the early twentieth century, and similar debates going on now in parts of Tuhoe Country, in Northland, and on the East Cape. The story of the revolt against conscription in Ireland during World War One reminds us of the

resistance to the same policy in the Waikato and Tuhoe Country at the same time.

But the connections between the fight for tino rangatiratanga and the fight for a free Ireland don't have to be deduced by academics or left-wing theorieticians: they've been grasped by the fighters themselves. It was a group of Irish Fenian miners calling themselves the tribe of 'Aorihi' who supported Te Kooti during his war with the New Zealand state, selling him ammunition during secret meetings in Karangahake Gorge. It was Maori members of the Patu Squad jailed in Mt Eden in the aftermath of the 1981 Springbok Tour who wrote to Bobby Sands and the other hunger strikers in Long Kesh prison to express their solidarity with the Irish cause.

I settled on the veteran Irish Republican Ruairi O'Bradaigh as a subject about a month ago, because he seemed, like EP Thompson before him, to be a man whose ideas are profound enough to transcend the political circumstances which prompted them. That doesn't mean, of course, that his ideas are necessarily correct.

O'Bradaigh's involvement in an armed struggle inevitably makes it more difficult to discuss his work in a detached way. In countries distant from a national liberation struggle there is always a danger of either romanticising or automatically condemning the protagonists of that struggle. My father-in-law is a veteran of an Irish band which played the Auckland and Waikato pub circuit in the eraly 1990s, and he recalls how he'd often be asked to play a song celebrating some IRA raid or bomb in the middle of happy hour or a raucous function. He always refused, because he was disgusted by the idea that the bloody details of war could be fitted snugly into a song and a good night out on the other side of the world.

I can understand my father-in-law's criticism of the easy romancing of the Troubles, but the kneejerk condemnation of the IRA and Sinn Fein in the media and amongst my schoolteachers during the 1980s was surely just as smugly self-righteous.

Looking back, I can appreciate how differently the wars in South Africa and Ireland were presented in the media and in classrooms during the '80s. Both the IRA and the ANC were killing people with bombs, organising riots, and engaging in peaceful politics by holding rallies and distributing propaganda, but the media and my Social Studies teachers seemed always to emphasise the violence of the Irish, and the peaceful actions of the Africans. Nelson Mandela, who with every justification had waged a bombing and shooting campaign against the South African state, was presented as a second Gandhi, while Martin McGuinness and other IRA leaders, who were waging a similar sort of campaign in Nothern Ireland, were likened to Nazis.

Of course, both romancing and demonising are ways of avoiding investigation and reflection, and the sort of uncomfortable ambiguity which is such a common result of investigation and reflection.

I have been intermittently lost in the forest of literature on the Troubles over the past month, and what follows is an appallingly long draft of an abstract for an essay about Ruairi O'Bradaigh and the British left. It represents a hunch rather than a firmly-held point of view. I apologise fulsomely to the unfortunate pair of scholars who made the mistake of asking me to write something for them. I'll list and discuss some of the sources on O'Bradaigh in a later post.

]

Outside the machine: notes on Ruairi O'Bradaigh

Historians of left-wing politics in the British Isles tend to associate the year 1956 with two seminal events: the neo-colonial Anglo-French invasion of Egypt, which prompted huge demonstrations and helped politicise a generation of young Britons, and the exodus from Britain's Communist Party caused by Hungary's anti-Stalinist revolution and the obscene sight of its repression by Soviet tanks.

There is, however, a third important event of 1956 which has seldom attracted much attention from scholars of the left. On the 12th of December 1956 one hundred and fifty Irish Republican Army volunteers descended on a variety of targets across Northern Ireland. A radio transmitter was bombed, a courthouse was burned, and a police post and army barracks were attacked. The assaults marked the beginning of the IRA's 'Border Campaign', which involved more than three hundred violent incidents in 1957 alone and would not end until 1962. In response to the campaign, both the British and Irish governments interned hundreds of their citizens without trial. Some of the internees were held for years. In its early years, especially, the Border Campaign aroused great support in Ireland. Fifty thousand mourners turned out for the funeral of the first volunteer killed in the campaign, and a number of IRA fighters were elected to parliament in southern Ireland’s 1957 general election.

On the 12th of December 1956 a twenty-four year-old named Ruairi O'Bradaigh was the deputy commander of the IRA's Teeling Flying Column, which crossed the border into the north looking to ambush armed police and attack police posts. During the Border Campaign O'Bradaigh would quickly rise to prominence in the IRA and in the Republican movement as a whole. On the last day of December O’Bradaigh was arrested by southern Irish police after returning from a raid. O’Bradaigh was incarcerated, but in March he was elected to Ireland's parliament, and in September of the following year he escaped from internment and rejoined the IRA, which made him its chief of staff.

O'Bradaigh returned to his job as an Irish teacher in County Roscommon after the end of the Border Campaign, but he remained very involved in the Republican movement. After the outbreak of mass violence in Northern Ireland in the middle of 1969 he co-founded the Provisional IRA, and in 1970 he became President of the army’s political wing, Provisional Sinn Fein. He held this post until 1983, when he was pushed aside by Gerry Adams and a group of younger men from the north.

In 1986 O’Bradaigh left Provisional Sinn Fein in protest at the party's decision to abandon its policy of ‘abstentionism’ and recognise the legitimacy of the southern Irish state. He founded Republican Sinn Fein, a relatively small organisation which has been connected with the 'Continuity IRA', a splinter group of the Provisional IRA. Both Republican Sinn Fein and the Continuity IRA have been outspoken critics of the Good Friday Agreement and the role of Adams' Sinn Fein in Northern Ireland's post-Good Friday government. O’Bradaigh led Republican Sinn Fein until 2009 and continues to represent the group at many public events.

During his early years as leader of Provisional Sinn Fein O'Bradaigh travelled frequently, explaining the party’s ideas and seeking support in Europe and America. Despite the war in Northern Ireland and its rhetorical commitment to anti-imperialism and confrontation with the state, Britain's radical left was often very dismissive of O'Bradaigh and his cause. The far left of the Labour Party, the Communist Party, and Trotskyist groups like the International Socialists all distanced themselves in various ways from both the methods and the message of the IRA and Sinn Fein. In the years since his split with Gerry Adams, O'Bradaigh has dropped off the radar of most of Britain's radical left. Active condemnation has given way to what Bordiga called 'the critique of silence'.

Irish Republicans have had a more ambiguous attitude towards O'Bradaigh. He is almost universally admired for his feats as a soldier in the 1950s and ‘60s and for his reputed integrity and selflessness. Many Republicans, though, have come to see O'Bradaigh as a quixotic figure, out of touch with modern Irish life and politics and wedded to noble but dangerously outdated notions of an endless armed struggle against 'the Brits'. Even some of the Republicans who reject the Good Friday Agreement and regard Adams' Sinn Fein with contempt see O’Bradaigh as a man of the past.

O’Bradaigh’s critics have frequently accused him of a ‘mystical’ and ‘legalistic’ attachment to the policy of abstentionism, and a ‘militarist’ hostility to progressive politics.

Under O’Bradaigh’s leadership first Provisional Sinn Fein and then Republican Sinn Fein maintained the traditional Republican refusal to acknowledge the legitimacy of both the six county statelet of North Ireland and the twenty-six county state in southern Ireland. Although they sometimes stood successfully for election to the Dail in Dublin, Stormont in Nothern Ireland, and Westminster in London, Sinn Fein members never took seats in these parliaments. Nor did members of O’Bradaigh’s organisations accept the legitimacy of the armies and police forces employed by the governments in Dublin and Belfast.

Abstentionists like O’Bradaigh look for inspiration to 1919, when more than seventy Sinn Feiners were elected to the Westminster parliament during an all-Irish election. Instead of travelling to London and taking their seats, the new MPs established a rebel parliament in Dublin and, eventually, a rebel state with its own army, police force, courts, and taxes. The abstentionist MPs saw themselves as representatives of the Irish Republic proclaimed during the 1916 Easter Rising, and helped direct the Irish Republican Army’s war against British authority in Ireland. After the partition of Ireland in 1922 many Sinn Fein members remained loyal to the Republic of 1916. The old Dail elected in 1919 continued to meet, and claimed to be the real source of authority in Ireland, even after the anti-partitionists had been defeated in the Irish Civil War of 1922-23.

In 1938 the surviving members of the 1919 parliament vested their ‘powers’ in the IRA’s Army Council. Since then, abstentionist Republicans have considered the Army Council to be the true government of all of Ireland. Under O’Bradaigh’s watch, volunteers who carried out bombings and shootings were told that they were acting on the orders of the Irish Republic established in 1916 and maintained by the IRA.

Ruairi O’Bradaigh has argued indefatigably against Republicans opposed to the policy of abstentionism. He co-founded the Provisional IRA in 1969 after a split over abstentionism, and he broke with Gerry Adams over the issue seventeen years later. O’Bradaigh’s critics accuse him of a romantic attachment to the events of 1916 and 1919, and a legalistic rather than realistic attitude to the contemporary Irish states. In the 1970s, even the more radical parts of the British left urged the IRA and Sinn Fein to abandon abstentionism and engage with the Dail and Westminster. Today, in the wake of the Good Friday Agreement and attempts to reform the Northern Ireland state, many Republicans see O’Bradaigh’s continuing rejection of Ireland’s actually existing parliaments as perverse.

But O’Bradaigh’s abstentionism has never been quite as ridiculous as his critics claim. O’Bradaigh has opposed participation in the Dail, Westminster and Stormont partly because he has been convinced that any Republican who enters those bodies becomes, in his words, ‘a part of the machine’ of imperialism and capitalism. O’Bradaigh believes that the careers of men like Michael Collins, Eamon de Valera, and Gerry Adams show the perils of entering ‘the machine’.

O’Bradaigh harks back to the Dail of 1919 because he admires the way that its members established their own revolutionary state alongside the British colonial state.

In an internal Sinn Fein document written in 1983, during the struggle with Adams over the direction of the organisation, O’Bradaigh argued that Provisional Sinn Fein and the IRA needed to organise a ‘big successful heave to topple the system’, rather than entering mainstream politics and ‘tinkering with the system’. O’Bradaigh suggested that Provisional Sinn Fein and the IRA emulate the Republicans of 1919 by creating ‘an alternative mechanism of government’ and thereby bringing about the ‘dual power situation which is the essence of revolution’. O’Bradaigh’s advocacy of abstentionism is not, then, a simple act of rejection. As well as opposing compromise with ‘the machine’, O’Bradaigh advocates a revolutionary alternative to politics as usual.

O’Bradaigh’s critics have also accused him of being hostile to left-wing politics, and of substituting military action for a rational political programme. It is true that, during the infighting which split the IRA and Sinn Fein at the end of the 1960s, O’Bradaigh opposed the faction of self-proclaimed socialists grouped around IRA leader Cathal Goulding. But O’Bradaigh’s objection was not to socialism so much as to Stalinism. He disliked the Soviet Union, seeing it as a ‘totalitarian’ society which oppressed nations on its fringes like Hungary and Czechoslovakia in much the same way that Britain oppressed Ireland. O’Bradaigh knew that Goulding and other leading members of his faction like Roy Jenkins had close connections with Moscow’s allies and apologists in the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Communist Party of Ireland. He feared that Goulding and co would try to turn Irish Republicanism into a tool of Soviet foreign policy.

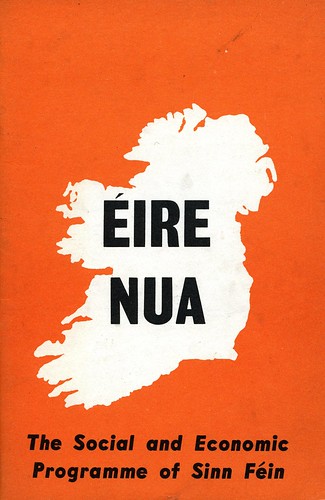

Critical of both 'Western capitalism' and Eastern bloc ‘state capitalism', O'Bradaigh has attempted since the 1960s to develop a distinctly Irish form of socialism. After the IRA’s Border Campaign ended in failure in 1962, O’Bradaigh had realised that Republicans needed to talk about economic and social questions as well as British imperialism. When he stood for Westminster parliament on behalf of Sinn Fein in 1966 O’Bradaigh emphasised not only his commitment to a thirty-two county Ireland and to abstentionism but his support for policies like the nationalisation of large Irish companies, controls on credit entering and leaving the country, and limits on the size of farms. In his articles for the Republican press O'Bradaigh began to quote James Connolly’s warning that Irish independence would be 'in vain' if it were not accompanied by the establishment of a 'just social and economic system'. O’Bradaigh did not only look to Connolly and other left-wing Republicans for inspiration, as he developed his ideas: he kept a close eye on the world beyond Ireland, and in was able to study in some depth subjects like the Algerian anti-colonial struggle and Tanzanian leader Julius Nyrere’s experiments with ‘African socialism’.

In his 1970 article 'Restore the Means of Production to the People', O’Bradaigh argued that the decentralised, communal nature of the pre-capitalist Irish economy could be a model for a modern system which avoided the individualism of capitalism and the authoritarianism of the Soviet bloc societies. O'Bradaigh repeated his argument for the nationalisation of strategic assets and industries, but he favoured placing small-scale industries under the control of local cooperatives. He advocated limiting the power of central government, and giving considerable autonomy to Ireland's regions.

O'Bradaigh argued that Ireland suffered from a 'triple minority' problem, pointing out that the Protestants, the nationalists trapped in Northern Ireland, and the Irish-speakers of the west of the country were all vulnerable groups whose rights needed to be protected. A decentralised state and economy were the way to do that. In the 1970s, as he struggled to negotiate a peace deal in Northern Ireland, O’Bradaigh repeatedly insisted that the Protestants of the north were 'part of the Irish nation', and criticised Republicans who wanted to subject them to the rule of the 'confessional' state which had been established in the south after 1922. O’Bradaigh’s vision of a multi-polar Ireland enabled him to meet and dialogue with Protestant politicians who usually refused to go near Republicans.

Many of O'Bradaigh's ideas became Provisional Sinn Fein policy. His vision of a decentralised Ireland was reflected in the Eire Nua policy, which called for the country to be split into four self-governing provinces, including a twelve-county Ulster. A federal government based not in Dublin but in the small County Westmeath town of Athlone would have responsibility for Ireland's foreign policy and defence.

When Adams and his allies pushed O'Bradaigh out of power they did so partly by attacking his vision of a postcolonial Ireland. Adams and his supporters appealed to sectarian hatred of Protestants in an effort to discredit O'Bradaigh's Eire Nua policies. They characterised the notion of a self-governing Ulster province as a sop to Orangemen, and insisted that Ireland's Protestants should have to accept domination by a Dublin-based government. Cynically employing 'orthodox' Marxist language and appeals to the authority of the Soviet Union to win over left-wing grassroots members of Sinn Fein, some of O'Bradaigh's opponents condemned his proposals for workers cooperatives and an agrarian socialism as reactionary and utopian.

In recent decades the end of Cold War historiographical orthodoxies, the publication of long-unseen manuscripts, and the efforts of scholars like Karl Anderson and James D White

have helped bring attention to the later Marx’s belief that socialism could be built on pre-capitalist foundations in agrarian or semi-agrarian societies on the periphery of the global economy. Marx’s late claims about the revolutionary potential of the Russian peasant commune and the Iroquois Federation contradict the dogmas of Stalinism, and resonates with some of O’Bradaigh’s ideas.

O’Bradaigh’s political vision has not been realised in Ireland, but in other places there are signs that it might not be as quixotic as some critics have made out. The rural-based development schemes and state-sponsored cooperative movement in contemporary Venezuela might almost have been based on the blueprint O’Bradaigh laid out in ‘Restore the Means of Production to the People’. O’Bradaigh’s notion of a decentralised postcolonial society finds a parallel in Evo Morales’ Bolivia, which is experimenting with what indigenous activist and scholar scholar Jose Aylwin calls a

‘multinational state’ in an effort to reverse the centuries-long oppression of the Aymara and Quechua peoples.

O’Bradaigh’s ideas may have considerable value for indigenous peoples' movements in regions like Polynesia, Melanesia, and North America, where abstentionism and the

construction of institutions of ‘dual power’ have been common tactics amongst peoples faced with powerful colonial and postcolonial regimes. Some of O'Bradaigh's ideas may well transcend his location and the complicated and sometimes tragic story of his career. He is thinker who deserves serious attention rather than ridicule.

As it discusses how to deal with the success of nationalism in Scotland and Wales, and confronts the problem of how to advocate socialism in a deindustrialised society, Britain’s radical left could do worse than consider the thought of Ruairi O’Bradaigh.

When Skyler and I set out for the southern greenbelt of Auckland last weekend we decided to travel down the Great South Road, with its semi-permanent roadworks and spiteful traffic lights, rather than on the smooth fast Southern Motorway, which is insulated from the suburbs it bisects by brown noise walls and by great earthen banks covered in huddling shrubs. Perhaps because of its languid pace and its lack of necessity, our journey down the Great South Road began to take on a curiously luxurious feel, like some cruise down a slow-moving river.

When Skyler and I set out for the southern greenbelt of Auckland last weekend we decided to travel down the Great South Road, with its semi-permanent roadworks and spiteful traffic lights, rather than on the smooth fast Southern Motorway, which is insulated from the suburbs it bisects by brown noise walls and by great earthen banks covered in huddling shrubs. Perhaps because of its languid pace and its lack of necessity, our journey down the Great South Road began to take on a curiously luxurious feel, like some cruise down a slow-moving river.