Caving with Nicky Hager

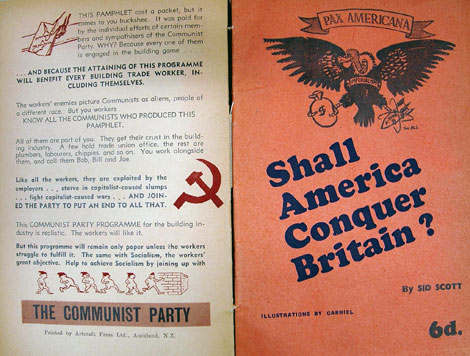

When Nicky Hager's revelations about the Key government's campaign of dirty tricks against its opponents irrupted into the media, Paul Janman and I were looking at this photograph, which was printed in the New Zealand Herald on September the 5th, 1940.

The caption under the photograph reads:

COMMUNIST LITERATURE FOUND IN PAPATOETOE CAVE: Cyclostyled pamphlets in a deep cave on the farm near Papatoetoe where the police have seized a duplicating plant and other material.

Paul and I discovered the image in the online Papers Past archive while we were researching our documentary film about the history of the Great South Road. When we exhibited a tableload of artefacts from the history of the Great South Road at Papakura Art Gallery earlier this year, we blew up the 1940 photograph and its caption and placed it next to a newspaper article that described the detention without trial of the South Auckland rangatira Ihaka Takanini during the Waikato War. We wanted to suggest that the repression of civil liberties has been a recurrent feature of New Zealand history.

This week Paul and I were throwing together images and footage from the whole one hundred and fifty-three year history of the road - images of the British soldiers and Maori guerrillas from the 1860s, but also pictures of the industrial zones of Otahuhu and Southdown during their heyday, and shots from the kava circles of Tongan immigrants to 'Atalanga - as we worked on a promotional clip.

We wanted to juxtapose images from different eras, so that we could show the continuities and repetitions in the history of New Zealand. When a voice from the radio in the corner of Paul's editing suite began explaining that the Key government had used spies, bullyboy bloggers, and hackers to intimidate and ridicule its opponents, the photograph taken in that cave began to look not only eerie but premonitory.

To understand why communists were hiding out in a South Auckland cave in 1940 we have to do some remembering.

By the 1930s the slaughterhouses and workshops of Southdown and Otahuhu had become citadels of socialist politics. Even after his Labour party won the general election of 1935 and made him Prime Minister, Michael Joseph Savage would visit the Otahuhu railway workshops and the freezing works in Southdown, mount an improvised stage, and speak to crowds of workers. He might have been an Athenian democrat talking to the city’s assembly, or a Roman senator addressing his plebian supporters.

The Communist Party never won more than a few thousand workers to its banner, but the discipline and masochism of its members, and their concentration in working class strongholds like Otahuhu, meant that the party was able to act as a left opposition to Labour inside several important trade unions. Party members endured discrimination from employers, raids by the police, and ridicule in the media to spend their mornings at the gates of factories selling their newspaper, the People’s Voice, and their evenings in unheated union halls reading Marx and Engels to yawning miners and wharfies.

The caption under the photograph reads:

COMMUNIST LITERATURE FOUND IN PAPATOETOE CAVE: Cyclostyled pamphlets in a deep cave on the farm near Papatoetoe where the police have seized a duplicating plant and other material.

Paul and I discovered the image in the online Papers Past archive while we were researching our documentary film about the history of the Great South Road. When we exhibited a tableload of artefacts from the history of the Great South Road at Papakura Art Gallery earlier this year, we blew up the 1940 photograph and its caption and placed it next to a newspaper article that described the detention without trial of the South Auckland rangatira Ihaka Takanini during the Waikato War. We wanted to suggest that the repression of civil liberties has been a recurrent feature of New Zealand history.

This week Paul and I were throwing together images and footage from the whole one hundred and fifty-three year history of the road - images of the British soldiers and Maori guerrillas from the 1860s, but also pictures of the industrial zones of Otahuhu and Southdown during their heyday, and shots from the kava circles of Tongan immigrants to 'Atalanga - as we worked on a promotional clip.

We wanted to juxtapose images from different eras, so that we could show the continuities and repetitions in the history of New Zealand. When a voice from the radio in the corner of Paul's editing suite began explaining that the Key government had used spies, bullyboy bloggers, and hackers to intimidate and ridicule its opponents, the photograph taken in that cave began to look not only eerie but premonitory.

To understand why communists were hiding out in a South Auckland cave in 1940 we have to do some remembering.

By the 1930s the slaughterhouses and workshops of Southdown and Otahuhu had become citadels of socialist politics. Even after his Labour party won the general election of 1935 and made him Prime Minister, Michael Joseph Savage would visit the Otahuhu railway workshops and the freezing works in Southdown, mount an improvised stage, and speak to crowds of workers. He might have been an Athenian democrat talking to the city’s assembly, or a Roman senator addressing his plebian supporters.

The Communist Party never won more than a few thousand workers to its banner, but the discipline and masochism of its members, and their concentration in working class strongholds like Otahuhu, meant that the party was able to act as a left opposition to Labour inside several important trade unions. Party members endured discrimination from employers, raids by the police, and ridicule in the media to spend their mornings at the gates of factories selling their newspaper, the People’s Voice, and their evenings in unheated union halls reading Marx and Engels to yawning miners and wharfies.

In 1940 the Communist Party and its publications were effectively banned, because they were opposing, on Soviet instructions, the war against Hitler. With the help of Christian pacifists, communists had organised a series of big rallies against the conscription of young men for the war. Communists caught with copies of the People's Voice or posters advertising anti-conscription meetings were tried and imprisoned, to the delight of Labour strongman Peter Fraser. Like several other members of Labour's cabinet, Fraser had been imprisoned for opposing the First World War using the same sort of rhetoric that the Communist Party now deployed.

Soon Sid Scott, the party's dourly prolific polemicist and pamphleteer, and Gordon Watson, a young poet and scholar who had shocked his bourgeois Wellington family and his university masters by converting to communism in the early ‘30s, were entrusted with the job of publishing an underground version of the People’s Voice. They took their mission literally, and set up a crude printing machine in a lava cave near the freezing works and railway workshops of Southdown and Otahuhu.

By 1940 New Zealand's reserves of paper and ink were carefully monitored, and only publishers whose politics were acceptable to the government were entitled to supplies of the precious materials. Scott and Watson presumably had to scavenge old pages and inkpots from the desks and cupboards of party members and supporters, and issues of their underground People's Voice often consisted of a mere four pages of badly smudged print. Copies of the paper were nevertheless passed through the worksites of New Zealand's big cities, along with leaflets with titles like For Peace and Labour Imperialists. More subversives were tried, and detention camps were improvised to complement New Zealand's prison system.

Near the end of the winter of 1940, some kids exploring the back paddocks of a farm found the entrance to a cave. As the New Zealand Herald explained, the outlaws were absent when the children visited, but their traces were obvious:

By 1940 New Zealand's reserves of paper and ink were carefully monitored, and only publishers whose politics were acceptable to the government were entitled to supplies of the precious materials. Scott and Watson presumably had to scavenge old pages and inkpots from the desks and cupboards of party members and supporters, and issues of their underground People's Voice often consisted of a mere four pages of badly smudged print. Copies of the paper were nevertheless passed through the worksites of New Zealand's big cities, along with leaflets with titles like For Peace and Labour Imperialists. More subversives were tried, and detention camps were improvised to complement New Zealand's prison system.

Near the end of the winter of 1940, some kids exploring the back paddocks of a farm found the entrance to a cave. As the New Zealand Herald explained, the outlaws were absent when the children visited, but their traces were obvious:

In addition to the duplicator, which was mounted on rough flooring boards, two boxes were found. One box contained a number of publications on communism...Pieces of timber and sacks covered the sodden soil of the floor, and two pieces of asbestos board had been used to protect the duplicator and papers from the moisture dipping from the roof. An empty apple box had also been used. The depth and winding access to the cave prevented any natural light from penetrating, and candles had been employed for illumination.

Neither Sid Scott nor Gordon Watson ever joined their comrades in jail. They eluded police and published their paper from other locations - one newspaper report suggested that a printer was working secretly somewhere in the Otahuhu Railway Workshops - until the middle of 1941, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and Stalin explained to his Western satellites that the Second World War had turned from an 'inter-imperialist conflict' into a struggle to defend socialism. In New Zealand RAK Mason, another poet who had converted to communism, was entrusted producing a new, ostentatiously pro-war publication called In Print, which was quickly legalised by the government. Mason was chosen for the job partly because he had not helped publish the underground People's Voice.

After the Soviet Union ordered the Communist Party to change its position on the war Watson became a soldier. When he died in the rubble of a small Italian town, a couple of weeks before the fall of Berlin, the Communist Party proclaimed him a hero. In 1947 the poems, articles, and letters Watson had written for the party press and to party members were collected in a memorial volume by Elsie Locke; all of them show signs of thoughtfulness and vivacity, but most of them are compromised by their author's belief that Stalin's Soviet Union is an Empire of the Blessed.Neither Sid Scott nor Gordon Watson ever joined their comrades in jail. They eluded police and published their paper from other locations - one newspaper report suggested that a printer was working secretly somewhere in the Otahuhu Railway Workshops - until the middle of 1941, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and Stalin explained to his Western satellites that the Second World War had turned from an 'inter-imperialist conflict' into a struggle to defend socialism. In New Zealand RAK Mason, another poet who had converted to communism, was entrusted producing a new, ostentatiously pro-war publication called In Print, which was quickly legalised by the government. Mason was chosen for the job partly because he had not helped publish the underground People's Voice.

Sid Scott continued to toil for the party after the abandonment of the People's Voice. In 1942 his eyesight suddenly deteriorated, and he was forced to dictate his articles and pamphlets to party secretaries. After being told that he had would lose his sight altogether, Scott took a holiday to the King Country, explaining that he had always wanted to see the famous limestone cave at Waitomo. Scott had enough eyesight left to make out a few faint glow worms, as he floated in a dinghy down Waitomo's dark current.

Scott turned against the Communist Party after the Soviet Union's invasion of Hungary in 1956, and eventually became angrily and outspokenly anti-communist, writing letters to members of the Holyoake government demanding repressive measures against the party he had once led. One of Scott's denunciations of his old comrades found a home in the New Zealand Herald.

It would be wrong to conflate the abuses of state power exposed by Nicky Hager with the repression suffered by activists like Gordon Watson and Sid Scott seven and a half decades ago. The Key government is not at war, and has no need of the special courts and detention camps that Peter Fraser built for his opponents. But Hager's revelations and the sinister photograph that appeared in the Herald in 1940 both remind us that New Zealand governments have a long history of persecuting their opponents.

Paul and I have located the cave where New Zealand's communists hid their printery in 1940. We'll be visiting the place soon - and you'll be invited along.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

2 Comments:

Thanks for the picture and the poem. The poem was good considering the time and that Watson didn't pursue poetry (it seems).

I'm not sure if that is the cave I went into (we didn't go very far in). But that is interesting. I'm pleased I kept that copy of Sid Scott's book.

I can understand how these things come about. The distances were much greater, news was sparse: and once you commit, your idea is that Socialism leading to the greater (in theory real democracy) egalitarianism of Communism (there is no way of showing that Communism cant, in some form, work...as indeed it is a classless system requiring total control by the people for themselves using democratic means. Unfortunately the USSR, even under Lenin, due to undemocratic methods amongst workers, deteriorated fairly quickly to a kind of dictatorship by the elite of the Communist Party, who, thus, were not really a Communist Party. Meanwhile Sid Scott and Watson and others believed and desperately wanted (and wanting) a better system, free of war and much injustice etc) acted in the belief that the USSR was a kind of worker's paradise. The Soviet Union made much progress though, but it is a mistake to be uncritical, which is why I was always wary of the rhetoric of the CP people and of the People's Voice. But even in 1970 it was something different. Many of the things in it, while infested with Marxian and NZ left wing cliches, were, in general right. There was collusion with the Unions. It was a real issue whether they should support war, as indeed many of Savage's quite cynical Government were Pacifists when it suited them, but once they gained power, they betrayed the workers and the Unions.

So they were on the right path in spirit so to speak.

Many good men and women were pacifists in both wars. So, in principal they were not so wrong.

Regardless of Stalin. The general reality of war (and the First World War was the war that many (on either 'side'), quite rightly I feel, opposed supporting.

Their struggle in the cave to print was an ethical, moral, philosophical dilemma: a question of freedom of speech which was what Hitler and others had shut down. Auden was right to be skeptical of all governments.

'Private faces in public places

are wiser and kinder

than public faces in private places."

Epilogue to 'The Orators' by W. H. Auden.

The Labour Government were wrong to jail them: they were hypocrites who, like all such bourgeois politicians in 'parliamentary democracy', were seeking power and money. Their conscience was at a minimum.

They have never been, and still aren't much better or very different to National.

Thanks Bos.

De Nature Indonesia

De Nature Indonesia asli

De Nature asli

De Nature

De Nature Indonesia Asli

Obat Sipilis Tradisional

Post a Comment

<< Home