Why we shouldn't censor the books we hate

[With the support of many other parents, Eileen Joy has been demanding that Auckland public library remove American evangelists Michael and Debi Pearl's book How to Train Up a Child from its shelves. Joy points out that the Pearls' book advises parents to punish their offspring by whipping them with willow branches, forcing them outside in cold weather, and denying them meals.

Auckland's library has defended itself by pointing that it holds a single copy of the Pearl's book, that the copy was requested by a patron, and the book is classified as a religious text rather than a manual on parenting. Here's a comment I left on Giovanni Tiso's blog, where an interesting debate about censorship and libraries has begun.]

Some of the people condemning How To Train Up a Child on Facebook seem to want it banned simply because it offends them. That troubles me.

If New Zealand's libraries begin to cut books from their shelves because of campaigns by offended patrons, then I fear that they will quickly become clear felling zones. I suspect that Paul Moon's This Horrible Practice, which deals problematically with Maori cannibalism, would not last long in the Kaikohe public library, and that James Belich's revisionist histories of the Maori-Pakeha wars would be cleared efficiently from the library shelves of conservative cow towns in the Waikato.

I can imagine opponents and proponents of Nicky Hager starting their own petitions, and some unfortunate librarian being forced to tot up signatures and make the decision least offensive to library patrons.

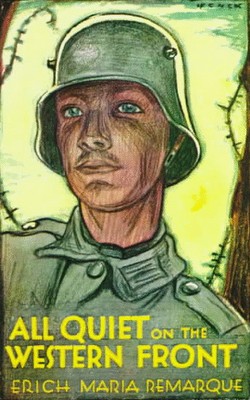

I suspect that, once they knew that their book choices could be vetted and corrected by offended members of the public, librarians would return to their old practice of unhappy self-censorship. In 1929 Auckland, Wellington, and Dunedin's public libraries banned Erich Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front, despite the fact that the book had been cleared for sale in New Zealand by censors, because they feared its gross account of life and death in the trenches of World War One would upset too many patrons. Scores of other important books suffered the same sort of pre-emptive strike in the first three quarters of the twentieth century.

Like the Cantabrians who recently demanded the removal of an offensively anti-Christian T shirt from their museum, the Aucklanders calling for the cutting of How to Train Your Child from their library on the grounds that it is offensive show a misunderstanding of the role that public cultural institutions play in free societies.

Just as a museum does not endorse or denounce the artefacts it exhibits, but rather uses them to tell true stories about humanity and its past, so a library does not endorse or denounce the books it holds, but rather uses them to show something of the range and intensity of opinions held by the human species. Museums and libraries should be sites of debate, where both popular and unpopular ideas can be heard and judged, rather than places that reaffirm the values of a society's dominant group.

I visited a large library in South Auckland a couple of weeks ago to hear a friend give a talk on Pacific history. While I was waiting for the lecture to begin, I grazed the shelves of the library's Pacific section. Amidst Albert Wendt's novels and Adrienne Kaeppler's homages to Tongan dancers and sculptors I spotted an ugly black and white cover stamped with the words The Parihaka Cult.

The book was written by Kerry Bolton, a former member of the New Zealand Fascist League and the National Front, and the author of such classics of contemporary conspiracy theory as The Holocaust Myth and The Banking Swindle. In the introduction to The Parihaka Cult, Bolton compares the movement led by Te Whiti and Tohu to Nelson Mandela's African National Congress and the American Civil Rights movement. For most people, such comparisons would imply a compliment, but for Bolton they are meant to show that Parihaka's protesters were part of an enormous, centuries-old conspiracy to defraud and demean the white race.

I have personal as well as ideological reasons for disliking Bolton. A few years ago he complained about some references I made to him on Radio New Zealand, and a long, complicated, and well-publicised court case followed. Bolton's complaints against me were eventually dismissed, but I had to waste time and nervous energy helping Radio New Zealand defeat him.

When I saw Bolton's defence of the Aryan race sitting in the middle of the Pacific section of a large library in South Auckland, I had a great desire to pull the book off its shelf and drop it in the nearest rubbish bin. But I didn't do this, for the same reason that I don't want Auckland libraries to rid themselves of Michael and Debi Pearl's equally grotesque book. Both texts represent part of the spectrum of opinion in our society, and both were requested by library patrons.

Instead of fearing that our fellow Aucklanders will turn into child abusers or fascists because they encounter To Train Up a Child or The Parihaka Cult, we should have confidence in the ability of our libraries to help win arguments against child abuse and fascism. I certainly don't think that Bolton's beliefs about the inferiority of Polynesian to European culture will impress anyone who encounters Adrienne Kaeppler's meticulous and passionate studies of Tongan carving and dancing, or Albert Wendt's brilliant fusion of Albert Camus and traditional Samoan storytelling.

I hope Auckland's libraries go on offending their public.

Footnote: Russell Brown has pointed out that Giovanni Tiso and Eileen Joy do not rely simply on the offensiveness of How to Train up a Child when they argue against stocking the book. They note that the book advocates and describes illegal activity that has harmed people, and suggest that it should be removed from libraries on these grounds. Here's a response I've made to them in the discussion thread at Giovanni's blog:

If a principle or precedent is set saying that books which promote and describe illegal activity that has a history of harming people shouldn't be stocked by libraries, then the door is opened for challenges to any number of volumes.

Let me give a couple of examples.

It's not hard to imagine somebody like Colin Craig or Bob McCroskie or the Taxpayers Union issuing a demand that a new edition Mike Haskins' popular Drugs: a user's guide not be purchased by Auckland Public libraries. Haskins' book talks enthusiastically and in detail about how to manufacture and consume various drugs that have, over the years, harmed or killed considerable numbers of people.

Sadie Plant's brilliant book Writing on Drugs does the same thing, in more elegant prose.

It is all too easy to imagine a wave of public opinion building in support of a campaign against these books. Who would want to read them, Colin Craig et al would ask, except meth manufacturers and cannabis growers looking to upskill? And why should public money be spent promoting books that promote illegal and harmful activities?

Although I don't use any illegal drugs, unless you count strong Fijian kava, I am fascinated by the history of hallucinogens and opiates, and by their relationship with creativity in both European and Pacific societies. I've used Plant's book as a reference in some of my writing on Tongan shamanism, art and drug-taking.

I fear, though, that if the principle that a book which advocates and describes illegal and sometimes harmful activity should not sit in a public library were established, then it would be very difficult to resist a campaign against Haskins' and Plant's books.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Auckland's library has defended itself by pointing that it holds a single copy of the Pearl's book, that the copy was requested by a patron, and the book is classified as a religious text rather than a manual on parenting. Here's a comment I left on Giovanni Tiso's blog, where an interesting debate about censorship and libraries has begun.]

Some of the people condemning How To Train Up a Child on Facebook seem to want it banned simply because it offends them. That troubles me.

If New Zealand's libraries begin to cut books from their shelves because of campaigns by offended patrons, then I fear that they will quickly become clear felling zones. I suspect that Paul Moon's This Horrible Practice, which deals problematically with Maori cannibalism, would not last long in the Kaikohe public library, and that James Belich's revisionist histories of the Maori-Pakeha wars would be cleared efficiently from the library shelves of conservative cow towns in the Waikato.

I can imagine opponents and proponents of Nicky Hager starting their own petitions, and some unfortunate librarian being forced to tot up signatures and make the decision least offensive to library patrons.

I suspect that, once they knew that their book choices could be vetted and corrected by offended members of the public, librarians would return to their old practice of unhappy self-censorship. In 1929 Auckland, Wellington, and Dunedin's public libraries banned Erich Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front, despite the fact that the book had been cleared for sale in New Zealand by censors, because they feared its gross account of life and death in the trenches of World War One would upset too many patrons. Scores of other important books suffered the same sort of pre-emptive strike in the first three quarters of the twentieth century.

Like the Cantabrians who recently demanded the removal of an offensively anti-Christian T shirt from their museum, the Aucklanders calling for the cutting of How to Train Your Child from their library on the grounds that it is offensive show a misunderstanding of the role that public cultural institutions play in free societies.

Just as a museum does not endorse or denounce the artefacts it exhibits, but rather uses them to tell true stories about humanity and its past, so a library does not endorse or denounce the books it holds, but rather uses them to show something of the range and intensity of opinions held by the human species. Museums and libraries should be sites of debate, where both popular and unpopular ideas can be heard and judged, rather than places that reaffirm the values of a society's dominant group.

I visited a large library in South Auckland a couple of weeks ago to hear a friend give a talk on Pacific history. While I was waiting for the lecture to begin, I grazed the shelves of the library's Pacific section. Amidst Albert Wendt's novels and Adrienne Kaeppler's homages to Tongan dancers and sculptors I spotted an ugly black and white cover stamped with the words The Parihaka Cult.

The book was written by Kerry Bolton, a former member of the New Zealand Fascist League and the National Front, and the author of such classics of contemporary conspiracy theory as The Holocaust Myth and The Banking Swindle. In the introduction to The Parihaka Cult, Bolton compares the movement led by Te Whiti and Tohu to Nelson Mandela's African National Congress and the American Civil Rights movement. For most people, such comparisons would imply a compliment, but for Bolton they are meant to show that Parihaka's protesters were part of an enormous, centuries-old conspiracy to defraud and demean the white race.

I have personal as well as ideological reasons for disliking Bolton. A few years ago he complained about some references I made to him on Radio New Zealand, and a long, complicated, and well-publicised court case followed. Bolton's complaints against me were eventually dismissed, but I had to waste time and nervous energy helping Radio New Zealand defeat him.

When I saw Bolton's defence of the Aryan race sitting in the middle of the Pacific section of a large library in South Auckland, I had a great desire to pull the book off its shelf and drop it in the nearest rubbish bin. But I didn't do this, for the same reason that I don't want Auckland libraries to rid themselves of Michael and Debi Pearl's equally grotesque book. Both texts represent part of the spectrum of opinion in our society, and both were requested by library patrons.

Instead of fearing that our fellow Aucklanders will turn into child abusers or fascists because they encounter To Train Up a Child or The Parihaka Cult, we should have confidence in the ability of our libraries to help win arguments against child abuse and fascism. I certainly don't think that Bolton's beliefs about the inferiority of Polynesian to European culture will impress anyone who encounters Adrienne Kaeppler's meticulous and passionate studies of Tongan carving and dancing, or Albert Wendt's brilliant fusion of Albert Camus and traditional Samoan storytelling.

I hope Auckland's libraries go on offending their public.

Footnote: Russell Brown has pointed out that Giovanni Tiso and Eileen Joy do not rely simply on the offensiveness of How to Train up a Child when they argue against stocking the book. They note that the book advocates and describes illegal activity that has harmed people, and suggest that it should be removed from libraries on these grounds. Here's a response I've made to them in the discussion thread at Giovanni's blog:

If a principle or precedent is set saying that books which promote and describe illegal activity that has a history of harming people shouldn't be stocked by libraries, then the door is opened for challenges to any number of volumes.

Let me give a couple of examples.

It's not hard to imagine somebody like Colin Craig or Bob McCroskie or the Taxpayers Union issuing a demand that a new edition Mike Haskins' popular Drugs: a user's guide not be purchased by Auckland Public libraries. Haskins' book talks enthusiastically and in detail about how to manufacture and consume various drugs that have, over the years, harmed or killed considerable numbers of people.

Sadie Plant's brilliant book Writing on Drugs does the same thing, in more elegant prose.

It is all too easy to imagine a wave of public opinion building in support of a campaign against these books. Who would want to read them, Colin Craig et al would ask, except meth manufacturers and cannabis growers looking to upskill? And why should public money be spent promoting books that promote illegal and harmful activities?

Although I don't use any illegal drugs, unless you count strong Fijian kava, I am fascinated by the history of hallucinogens and opiates, and by their relationship with creativity in both European and Pacific societies. I've used Plant's book as a reference in some of my writing on Tongan shamanism, art and drug-taking.

I fear, though, that if the principle that a book which advocates and describes illegal and sometimes harmful activity should not sit in a public library were established, then it would be very difficult to resist a campaign against Haskins' and Plant's books.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

24 Comments:

I think a key point here is that How to Train Up a Child isn't simply a book that offends people (or a bad book that will supposedly make people who read it bad). There are lots of those and people have no right to not be offended. It is literally an instruction manual – and people who have followed its instructions have killed and injured their children. I'm still not quite sure what I think here, but that point is pertinent.

After recording more than half of the band "The Fast and the Furious 7" US operations ceased celebrated Thanksgiving, so filming had to be renewed on December 1st Atlanta Texas, and later in the United Arab Emirates. As reported by The Hollywood

watch Furious 7 Online Putlocker

If this was a manual on how to sexually abuse a child, and it was being used by parents, would you defend its right to be available in the library?

This is a manual on how to abuse your child, which is also illegal, and is being used by parents. If the first should be banned then so should this.

There's an unexamined leap in your argument, anon. Yes, this is a repugnant book, and yes, this is a book which advocates and describes illegal acts, but why should either of those facts lead ipso facto to censorship?

Why not keep the book on the shelves but condemn and if necessary argue against its contents? That's what I do with texts by the likes of Bolton.

If all books that described and advocated what we (rightly) today call child abuse were banned, then we'd have to strip dozens of important titles from our libraries. Ancient Greek writers like Theognis, novelists like Petronious and Andre Gide, and the great modernist poet Cavafy would all have to go.

I prefer to leave our libraries unpurged.

Because there is one act of censorship or restriction you seem to think that that is like a legal precedent. That is nonsense. I don't know the book, but it sounds to me that the libraries should simply keep it off the shelves. A book about drug making of illegal drugs? Leave that buried in a biochemical text book, the average person doesn't need to know about that. If they make the effort to study biochemistry and chemistry etc well they will learn about such things. But some things you leave out of the way.

Auden writes to the effect:

'You don't give a rifle to a melancholic bore.' (Interesting the adjectival pun he uses there I have always thought).

And I think as I did before that we dont need this shirt abusing other peoples' religions, as indeed I am quite convinced that Hebdo should have been shut down by the French Government.

There is a time and a place for censorship and sometimes satire, while it can be a powerful force in the hands of writers and artists, of course Swift is one of my favourite writers...but at the wrong time, taunting people is simply wrong and stupid. And you then, if you have been threatened with death, are asking to be killed if you carry it through.

But that doesn't mean that all satire or "offensive" writing has to be banned. It doesn't follow that the book about cannibalism, which I found well written and interesting, should be banned. If enough people were concerned, then maybe yes, pull the book, and then reinstate it if the debate shows that it needs to be part of the overall "discussion".

I think Bolton's book is more of the same, more or less harmless, (people wont go around finding all the things to ban and each book or art work or whatever will or can be judged on its own, these things aren't connected, precedent only applies some cases even in law) but books that talk about hurting children are more serious. That is something we need to ban.

Tiso one often thinks (or this may be unfair, perhaps he acts like one who has) has a rod of PC rigidly shoved up his righteous arse, but he cares, it seems, that is probably true - perhaps he only sounds as though he is the Judge of All Things Right and Wrong. If he takes some risk combating sex rings and corruption (o.k. we can lighten up a little on the young men with their very active testosterone etc, as pornography is everywhere, and it takes more than one to tango...but well...) and this book we need to take notice as although he is very and sometimes over PC he is indeed a highly intelligent and cultured man...

So I think generalisations here are no good, each book or case needs to be reviewed. Some things for some people can be quite traumatic, so there is a case for, for example, banning movies showing operations and blood and even shooting other people. We have possibly become too inured to it.

In the movie about Anne Frank there is not killing, no blood shed, and yet it is a deeply moving and disturbing film. That is a film that people should watch (but I agree with the warnings the censors make).

There is a good case for judicious censorship.

So, as I have been called 'verbose', and I am, I will sum up:

I support Tiso et al in this case in wanting to ban a book that advocates violence toward children.

'Because there is one act of censorship or restriction you seem to think that that is like a legal precedent.'

That's exactly what it would be, Richard. At present libraries aren't allowed to make judgments about the morality or offensiveness of a book when they consider requests from the public.

Librarians can only reject a book order out of hand when the book in question has been banned by the official censor. This is made quite clear by Auckland libraries in its public statement, and also by the anonymous librarian who commented at Giovanni's blog.

'So I think generalisations here are no good, each book or case needs to be reviewed.'

But how could generalisations be avoided, if the regime of censorship you're advocating were introduced?

Hundreds of different librarians around the country are handling requests for books: if policy were changed and they were given the power to reject books on grounds previously only given to the official censor, then either each librarian would be left to come to his or her own conclusions about what should and shouldn't be banned, or else some set of rules would have to be created to guide the decisions of individual librarians.

The first option seems obviously unworkable. The second option would necessarily involve all sorts of generalisations.

'A book about drug making of illegal drugs?..the average person doesn't need to know about that.'

I fear that, if this particulr generalisation were ever made nto a guideline for librarians considering book requests, then our libraries would lose Aldous Huxley, De Quincey, William Burroughs, and Will Self!

' Because there is one act of censorship or restriction you seem to think that that is like a legal precedent.'

/That's exactly what it would be, Richard. At present libraries aren't allowed to make judgments about the morality or offensiveness of a book when they consider requests from the public.

Librarians can only reject a book order out of hand when the book in question has been banned by the official censor. This is made quite clear by Auckland libraries in its public statement, and also by the anonymous librarian who commented at Giovanni's blog./

'O.k. Then in that case, the censor who overseas all books (and there HAS to be censorship) has to take a rational look at each book. In this case they need to censor such a book. Books are thrown out all the time, and in fact, there needs to be censorship before that.'

'So I think generalisations here are no good, each book or case needs to be reviewed.'

But how could generalisations be avoided, if the regime of censorship you're advocating were introduced?

No, in this case then, a decision has been made by either the librarian or a censor. There is no need for any generalizations.

In the case of a censor, given that good grounds are given (this case that harm will almost certainly be done by the book), can stop the book, have it destroyed. No problem there.

There have to be rules in certain clearly (commonsense cases).

A book about drug making of illegal drugs?..the average person doesn't need to know about that.'

I fear that, if this particular generalisation were ever made into a guideline for librarians considering book requests, then our libraries would lose Aldous Huxley, De Quincey, William Burroughs, and Will Self!

It doesn't need to be made into a guidelines, each book can be considered separately... I have read some of Huxley's books and none need censoring that I have read. Which book by him do you mean?

De Quincey doesn't talk about making drugs, I read his 'Confessions', it is a rightful classic, but it doesn't talk about making illegal drugs. He discusses his own use of opium which in the end he had to stop. At the time opium was not illegal and as it was cheaper than alcohol many people used it.

I read Burroughs book 'Junky' and it is a book that doesn't talk about drug making either. However it is a highly negative and depressing, and finally useless book. I don't see why it hasn't been banned. I don't know about his other books, the man was mentally sick in my view so we could do without his books.

I have seen a few books by Self and I wasn't impressed. I have no problem with his books being suppressed (if they are as bad as the ones I saw).

We certainly have no need of books that valorise drug taking. Added to that if they give ways of making illegal drugs that is another good reason for banning those particular books.

No one is going to wade through a book on biochemistry or pharmacy etc unless they already have some criminal intent. Alternatively, they are scientists or medical people. So the average teenager (say) is unlikely to be looking at such things (to make illegal drugs). If they are they are already on the way to illegal activities and of course you cant stop such a person finding things like that. We can however, suppress books that encourage people and in fact give them lists of what to use etc. You dont give a gun to a melancholic bore. The gun (relatively simplistic book about drug making) can go off very easily in the wrong hands, whereas the text book is not to easily activated. It is unlikely the unwashed are going to read it.

Your examples are not very pertinent.

There are many instances where books can and should be censored, just as films could be.

This wouldn't be done lightly. It could be done by a group of psychologists and others who have some wisdom and awareness of the dangers of such books as the one Tiso is discussing.

We are not talking about Plato's 'Guardians' though. Just people like judges who make such decisions every day.

I know that Huxley was keen on hallucinogens. I had a book on them and similar chemicals when I was a teenager as I belonged to the 'Scientific Book Club' but it didn't go into how these things were made. The book was very good but it was clear that there was a big danger that someone taking LSD for example would or could become psychotic. Now that was a book that didn't need to be banned as while it showed that certain near 'spiritual' experiences could be attained with LSD (something Huxley was always interested in, but of course he used such things and such as psilocybin (something if you are sick or crazy enough any (probably) Mexican could tell you where to get). But he had cancer and used it to relieve the symptoms.

But the book I had wasn't advocating or telling me how to set up a lab or whatever, just discussing the book. I was also studying chemistry but I had no interest in making explosives.

But an irresponsible book which told a reader how to make a bomb or illegal drugs (in the wrong context) is a different matter.

'a decision has been made by either the librarian or a censor'

But a set of rules, eg generalisations, already exist for the country's single official censor.

He doesn't just sit down, watch a film or read a book, and come to some sort of intuitive decision on whether said film or book is suitable. He's guided by a set of general rules, and if he has seemed to depart from them his decisions can be appealed.

The censor only looks at work which has been referred to him by members of the public. He doesn't consider every book or other cultural artefact that enters the public spehere. And the censor has experise in the law and in the history of censorship.

What you seem to be suggesting is that the hundreds of librarians who process requests for book purchases up and down the country should be empowered to act in the same way as the official censor.

This is a recipe for chaos, not to mention the repression of free speech, because each librarian would be forced to parse vastly more books than the official censor, and a degree in librarianship is hardly a preparation for the sort of job the oficial censor performs.

Contradictory decisions, personal prejudices, and local pressures would soon see us back in the situation we faced in 1929, when a book could be banned by one library but bought by another, and where fear of political consequences made many libraries close their doors to important books like All Quiet on the Western Front.

I don't actually think we need a censor at all, because if a book or some other cultural artefact is really injurious to the public in a direct and concrete sense then it probably already violates a law.

But the present system is certainly preferable to a situation where every librarian is given the powers of a censor.

Ah, I hadn't read as far down as this comment:

'I have seen a few books by Self and I wasn't impressed. I have no problem with his books being suppressed (if they are as bad as the ones I saw)'

I fear you are playing the tongue-in-cheek reactionary!

It is unfortunate that Huxley who wrote some excellent novels and the wonderful 'Texts and Pretexts' should have written a book distorting Blake's vision. It came as a metaphor for seeing more deeply into reality and had nothing to do with drugs: 'The doors of perception'

In that line Blake was also referring to the etching process that he used, that cleared away, so to speak, so as to 'see' the more deeply.

Unfortunately Huxley's book or essay was written and misused by the pop group 'The Doors' (named after this but they were probably ignorant of Blake's writings).

Blake has also been misunderstood by such as The Doors.

But the Huxley's were educated people and mostly highly responsible as for example his brothers (biologists), but it is unlikely that either of them or even Aldous Huxley would have written a book on how to make poisons for children.

No, I am in favour of censorship in many cases. People are not capable of living without rules. Take the simple rule of the road about stopping if someone is near a crossing. I have noticed that just about everyone stops as soon as anyone is even NEAR a crossing. The reason? A rule. And fear. The drivers are in terror that they will be caught by a cop, as they know there is a rule about crossings.

Now if I am crossing a road, and I am getting on, I NEVER has experienced anyone doing what they should do, that is, slow down. Instead, in some cases, people accelerate. Now a person crossing a road might stumble, might be ill, or if old have lost track. But I have never seen anyone slow down as a precaution. They are in fact so convinced they are in the right that they are ready to kill the pedestrian who to them, is IN THE WRONG.

Now this is how stupid the majority of people are. Not reactionary, just reality. They are not concerned about each other, well they aren't in New Zealand that's for sure, I believe that in the US, in some of the Southern States, they slow down if you are on the side walk, perhaps if you are of the right persuasion however! Not sure, this is hearsay.

So I think that people go by rules that serve themselves. If they think they are going to get a speeding fine they will slow down, and we reduce the road toll. That is exactly why I am glad when I recall the speeding tickets and quite severe drink driving penalties I received. The more severe they became the more I re-thought my drinking. Now that works for most people. We exclude those on the very bottom and murky rungs (criminal elements): but otherwise, the rules are there, or people would simply keep killing each other with great relish.

It is not reactionism, it is called realism.

No, not all the librarians. We need censorship. In cases such as this where a large concern is expressed by a fairly large section of the populace and I will be the devil's advocate, such as the rapier minded Comrade Tiso who Know all Rigteousness...

We don't have to go to ridiculous extremes, or flights of fancy about Will Self who writes about monkey men and other bizarre nonsense I believe (he seems a bit unhinged), commonsense can decide and a legally (and well educated) trained censor.

'I think generalisations here are no good...People are not capable of living without rules.'

It's hard to know how to reconcile these statements. You've gone from denying that general rules need to guide censors to extolling the virtues of such rules!

Interesting project here:

http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/banned-books.html

'I think generalisations here are no good...People are not capable of living without rules.'

It's hard to know how to reconcile these statements. You've gone from denying that general rules need to guide censors to extolling the virtues of such rules!

No, that was a confusion caused by your interpretation. You are trying to be a Socrates.

The point is fairly obvious. People need rules and guidelines. We would be a chaos without them. We also, contradictorily (it seems to some who are bound by these things as if hypnotized), need to be able to question those rules etc. Clearly though, we need them.

It is a question of degree. We don't want Plato's Republic, I have been reading that and, indeed, it is a terrible picture he is painting. It clearly is the background (cf. The Guardians etc) to 'We' by Zamyatin which I read recently as my friend James "Ant" Dolimore had read it in the wake of '1984' etc.

Of course we don't want all that stuff.

BUT there are censors, and we do restrict our own children from various things that are dangerous.

Adolescents are at a critical time of life. I would mostly not censor anything but there are books I would perhaps quietly keep out of sight of people especially young people.

By and large we need access to everything. Mostly it is there.

Now I thought that there was no overall censor (it seems there is). That is what I was thinking of. We do need such, unfortunately. Some things are simply not good, and in fact are dangerous, in the wrong hands if you like. We need to have judgment. We need some rules. Like road rules. Like laws.

Now I advocate general concepts that guide the "judges" but that we take each book or case on it's own, no need for a precedent as there is no necessary connection case to case (as in law, for good reasons, although there are some good examples of precedent they don't always help the lawyer in his or her case).

So no need to worry that Will Self will have all his books burnt because person X writing for adolescents or children does. You are, as usual, twisting things for your own political purposes.

In the meantime we have a specific book, advocating mistreating children (there may be others but we don't need to talk about them unless they are brought to our attention, and indeed it is unlikely there are hundreds of books as virulent as this one - let's assume it is as bad as Dr. Herr Tiso and company say - so it can be considered on it's own.

And banned as it upsets a lot of people. This is in fact an aspect of democracy. This might change. Later we might re-evaluate it. No problem, can be done. Put it back on the shelves as now more people think it will not affect people...

It is not so complicated. It can be done.

But in certain areas, unfortunately, a lot of people are not so wise and that is when we need those rules.

This is obviously an area where there are anomalies and a degree of uncertainty, but in fact, that is what the world is like. Your arguments actually probably lead more quickly toward 'The Republic' than those of the others.

But I don't want to see thousands of books banned. Some we could quietly retire though.

'[This books should be] banned as it upsets a lot of people. This is in fact an aspect of democracy.'

That was more or less the justification libraries used in '29 during the furore over All Quiet on the Western Front. The book had to be pre-emptively banned because it'd upset too many Kiwis. As it turned out, many people were upset by the banning of the book.

Most important books upset as well as enthuse large numbers of people, especially in the period after they first appear.

If you're going to ban books that upset a certain number of people, what's your threshold going to be? A petition with a thousand names? Ten thousand negative comments on facebook? And how are you going to weigh the positive comments a book receives besides the negative? A lot of people were upset by Paul Moon's This Horrid Practice, but many others enthused about the book. Are you going to tot up the pros and cons and then decide whether the book should be banned or not?

You seem to deliberately misread what I say. It is clear enough which things are harmful and which are not and why.

The book by Moon was well researched and as the 'furore' died away, it became less important. I read that book it was interesting and pretty good if upsetting to some.

There are other books and films etc that are clearly, to anyone with any sense, simply bad, and need to be suppressed. The are intelligent, well informed people, who can sort these things out.

So some guidelines, a committee if there is controversy and a censor. I have no idea how censorship works at the moment, but we have clearly declined in recent times.

But we can ignore the Unwashed on Face Book and Twitter.

'It is clear enough which things are harmful and which are not and why.'

There demonstrably isn't clarity about what cultural products are harmful, or this sort of debate wouldn't continually be flourishing.

Twitter and facebook are other parts of the internet are full of discussions about whether To Train Up a Child is harmful.

This time last year they were filled with arguments about whether Odd Future's future was harmful or not, as the band attempted to play a gig in New Zealand and was blocked by the Department of Immigration. Ninety years ago All Quiet on the Western Front was similarly divisive.

If the history of debates about censorship shows us anything, it is that different people have very different ideas about what is harmful.

But even if we agree that a book is harmful, we may disagree about whether or not it should be censored. I pointed out on twitter that Auckland libraries hold eleven copies of George Bush's book defending the invasion of Iraq and other deeds committed during his presidency, like the setting up of the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay.

I think that Bush's ideas have brought all sorts of harm to the world, and if his book has helped spread those ideas then it has caused harm. But I don't want to ban Bush's book from the libraries, any more than I want to ban John Roughan's recent hagiography of John Key or Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged or Henry Kissinger's memoirs.

So I don't think there's any easy agreement about which books are harmful, and I don't think a harmful should ipso facto be censored.

Yes, I agree that the issue is fraught with contradiction. I see that: the book about Bush and say Hitler's 'Mein Kempf' are important to people wanting to know the complexity etc of history. I am not for an overall censorship, but there are limits, which will never be as clear - or clear in any cold logical sense. I was tongue in cheek of course about Twitter and FB as I use FB and it is very good. I think that there is a place for some discernment. I think some books are somehow 'automatically' sidelined, which is a bit diff. to censorship.

During certain times of crisis it can be necessary. If books can clearly lead to harm or danger (books directed at teenagers telling them how to make drugs of bombs) there is a case for suppression. There are other cases.

Ironically, however, Remarque's book was censored when it was possibly needed most.

But we dont need an absolute, a system of limits and relative merits can be used. This means a mix of judicious guidelines and individual judgments.

In most cases the individual is not harmed.

Also, in a strange way, censorship is necessary as it is a kind of ritual we do. Humans also need the slightly mad, outre, outside etc. So censorship can act as a positive-negative force that may or may not enhance but makes more interesting the chaos we are in ... as we descend into the flames of the glorious Goterdammmerung!

Good post!

This comment has been removed by the author.

Post a Comment

<< Home