Enlightening New Zealand: an Open Letter to Philip Catton

like thousands of other New Zealanders, I encountered you for the first time one morning in January, when you appeared on Radio Live to counter host Sean Plunket's criticisms of your daughter. I admired your calm and cogent response to Plunket's claim that Eleanor Catton's criticisms of the National government made her a traitor to New Zealand. I admired your criticisms of Plunket's overbearing and obfuscatory manner, and nodded in agreement when you called for Kiwis to discuss ideas and issues in a more serious and respectful way.

Now, in an essay for The Pantograph Punch, you have again emphasised the value of 'many-sided public criticism and debate'. There is much in your essay that I agree with. I think you are right to convict John Key, as well as Sean Plunket, of a failure to engage respectfully with critics; I think you are right to say that politicians and media personalities who lack respect for their interlocutors suffer, at bottom, from a lack of self-respect and intellectual confidence.

I disagree, though, with the historical narrative that takes up part of your essay. In the spirit of respectful dialogue, I want to argue that you misunderstand the impact of Enlightenment thinking on New Zealand, and that you misunderstand the reasons for the growth of democratic values and institutions here.

About halfway through your essay you look away from contemporary New Zealand to eighteenth century Europe, and begin an extended tribute to the Enlightenment.

You argue that the Enlightenment 'founded the modern ideas and institutions of democracy'. You characterise the movement as an overdue response to the ignorance and violence of churches and kings. Repulsed by witch-hunting clerics and warmongering kings, cliques of European intellectuals gathered in salons and cafes. These intellectuals thought freely, and spoke freely, and promoted free thought and free speech as ideals. As their example spread through Western societies, a 'democratisation of thought began', and old, reactionary establishments were 'gradually shrunken and dissipated'. Kings became 'servants of the people', and clerics lost some of their moral authority.

Until the Enlightenment, you insist, human beings existed in a 'condition of self-imposed immaturity'. The habit of free thinking and the idea of democracy were alien to them. With the help of Enlightenment intellectuals, some humans have been able to 'awake' from their dogmatic slumbers. In the twenty-first century, though, too many people still languish in an ancient state of immaturity.

You argue that the Enlightenment occurred before New Zealand existed as a nation, and suggest that the 'courageous intellection' found in the cafes of Europe had no parallel here. Nevertheless, you concede, New Zealand has sometimes 'set quite a fine example' of 'democracy'. Presumably you believe that Enlightenment ideas found their way to this country in the nineteenth century, and helped produce the universal suffrage and relative freedom of speech that have become features of our society.

Of course, not all scholars of intellectual history share your enthusiasm for the Enlightenment. It is seventy years since Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer published The Dialectic of Enlightenment, a book that linked the Enlightenment passions for taxonomy and logic with the panoptic states built by Stalin and Hitler. And it is nearly forty years since Edward Said published Orientalism, a polemic that showed how many of the Enlightenment's greatest thinkers, from Voltaire to David Hume to Immanuel Kant, believed in the cultural and biological superiority of European peoples over other human beings.

Said argued that Enlightenment intellectuals showed an enormous contempt for the rest of humanity, when they condemned the world's cultural traditions as compendia of superstitions and blunders, and declared themselves the first humans to think reasonably and freely. Although most Enlightenment intellectuals believed in the ability of Europeans to awake from superstition and learn reason, many of them doubted that non-Europeans had the same chance. At worst, dark-skinned people were congenitally irrational; at best, they would have to be schooled in reason by Europeans.

Said and other scholars have suggested that Enlightenment thinking was very useful for Europe's great powers, as they colonised the rest of the world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Land grabs in Africa or Asia or the Pacific could be presented as attempts to bring the light of European reason to benighted corners of the world.

If we examine New Zealand's colonial history, it is easy for us to find evidence for Edward Said's dark vision of the Enlightenment.

Alfred Domett was one of the bridges between Enlightenment Europe and colonial New Zealand. Domett was Premier of this country in 1862 and 1863, and held several other important government posts. An atheist, a freethinker, and an advocate of modern science, Domett had befriended Robert Browning and other important British intellectuals before emigrating to New Zealand. Even as he pursued a political career in his new country, he published poems in fashionable British magazines, and polemicised for the Enlightenment in letters to his friends in the old country.

Alfred Domett was in no doubt about the enlightened way of treating the indigenous people of New Zealand. For him, Maori were an unreasoning race, thwarted by superstition and tribalism. 'It is unthinkable that savages should have equal rights with civilised men', he explained in one of his letters. Maori 'must be ruled with a rod of iron', he insisted, until missionaries and schoolteachers had given them 'a firm belief in the white man's domination'. As Premier, Domett oversaw the invasion of the Maori-controlled Waikato by thousands of British and colonial troops.

The Enlightenment belief that traditional cultures are irrational and useless informs much of the legislation that politicians like Alfred Domett gave New Zealand in the nineteenth century. After defeating their enemies in battle, the colonists abolished traditional Maori political structures, land ownership systems, and legal arrangements, and replaced them with ostensibly more rational and efficient institutions made in Europe. After New Zealand acquired a tropical empire the same process was repeated in Samoa, Niue and the Cook Islands.

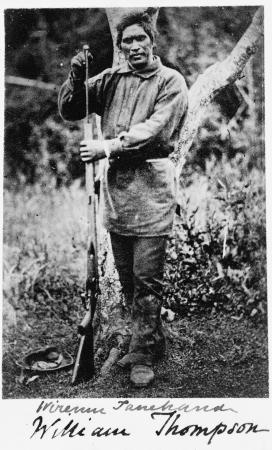

While men like Alfred Domett were starting wars and stealing land in the name of reason and civilisation, some of the indigenous people of New Zealand were building this country's first democratic institutions. At the end of the 1850s the Ngati Haua chief Wiremu Tamihana brought scores of hapu and iwi together to form the Kingitanga, or Maori King movement.

At Peria, the village he had founded near Matamata, Tamihana created an assembly house where the future of the King movement could be debated. Tamihana also helped found a newspaper where Kingites could share information and ideas. At the time Tamihana was creating these institutions, no Maori had the right to vote for the parliament of colonial New Zealand, and few Maori voices were allowed into Pakeha newspapers.

After the invasion and conquest of the Waikato and the death of Tamihana the Kingite parliament was reestablished, and named Te Kauhanganui. Its work continues.

Wiremu Tamihana can be called one of the fathers of New Zealand democracy, but his thinking and practice were inspired not by Descartes or Voltaire. When he created a parliament for the Kingitanga, Tamihana adapted one of the most important rituals in Maori culture. The powhiri involves a complex dialogue, as the tangata whenua of a marae welcome and then exchange speeches with their manuhiri, or guests. Tamihana recognised that, with its two-sided structure, the powhiri could be made into a forum in which information is shared and debates are waged.

Another force responsible for the growth of democracy and liberty in New Zealand was the workers' movement.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century trade unionists and their left-wing political allies struggled with employees and the colonial state for the right to recruit and rally members, and for the right to publish propaganda. They had to defy the Sedition Act, which was used to send the owners of books and pamphlets by Marx and Lenin and Rosa Luxembourg to jail, as well as local government bylaws that often forbade protest marches and public meetings. In certain periods of intense industrial conflict - during the Maritime strike of 1891, the Great Strike of 1913, and the Waterfront Lockout of 1951 - virtually all pro-union propaganda was forbidden, as soldiers and police confiscated printers and imprisoned union leaders. Only after many decades of agitation did the workers' movement win the right to publish and rally freely.

As the trade union movement grew, some of New Zealand largest worksites became strongholds of democratic debate. The Otahuhu Railway Workshops, for example, earned the nickname 'the working class university of New Zealand' because of its boisterous workers' assemblies and its many study groups. A photograph taken in the 1930s shows Michael Joseph Savage speaking from an improvised stage to a crowd of workers at the Otahuhu workshops. The look on Savage's face suggests that the workers of Otahuhu were as demanding an audience as any parliament.

Like Wiremu Tamihana and the Kingites who built Te Kauhanganui, the radical workers' movement owed little to the Enlightenment intellectuals you credit with founding democracy. Its members took their ideas from the overseas socialist movement, and from local left-wing intellectuals like RAK Mason and Elsie Locke.

I have been talking very negatively about the Enlightenment. I should admit that the movement's members produced good as well as bad ideas, that they were capable of courage as well as bigotry, and that their thought could be used for righteous as well as evil ends. David Hume may have considered persons with dark skin subhuman, but his lonely atheism demands respect. It is hard to imagine the French revolution occurring without the help of Voltaire, and EP Thompson has shown how the rebellious plebians of nineteenth century England were sometimes inspired by local representatives of the Enlightenment like William Godwin. In New Zealand and many other colonial societies, though, the Enlightenment has cast a shadow.

It might seem like I have made a great deal of what was, after all, only one section of your essay. But I think that it is important to recognise the contradictory and often ugly nature of the Enlightenment, and to remember how democracy and liberty were established and expanded in New Zealand.

If we understand how fine rhetoric about reason and civilisation can be deployed in the service of conquest and plunder, then we have a better chance of making sense of the events of the twenty-first century. The disastrous Western adventures in Afghanistan and Iraq, for example, have been justified with Enlightenment-style talk about the bringing of human rights and freedom to benighted parts of the globe. Alfred Domett would have appreciated Bush and Blair's apologies for war.

And New Zealanders are more likely to cherish and defend their civil liberties if they understand that these taonga were won, over many decades, from a hostile and often violent state. Our democratic rights were not made in the salons and coffee houses of Europe and imported by British colonists: they are the legacy of New Zealanders like Wiremu Tamihana.

Sincerely,

Scott Hamilton

25 Comments:

Just popped by your blog, hadn't visited for a while. Fascinating mini-history of Enlightenment kiwi-style. I'm always a bit wary about quoting those 18th century fellas, they can indeed by presented in a savage light. Just chanced upon this book, which has a free download attached, perhaps your readers will delve into it eagerly. I like to think the philosophical tradition combined with the Trade Union movement and solidarity movements among ethnic minorities to create a mighty happy and giant step forward for humankind. Cheers, and wishing your wife a successful and rapid convalescence. Hi to Cerian. William Direen. http://re-press.org/books/what-is-philosophy-embodiment-signification-ideality/

Ta muchly for that, Bill: will read! I know you;re interested in this sort of stuff, so I was going to mention that, in a corner of his (relatively) new book Beyond the Colonial Frontier: the contest for colonial NZ Vincent O'Malley provides a little more information on the mysterious Fenian rebel O'Connor, who is supposed to have sold bullets to Te Kooti and raised a republican army, or at least brigade, inside the King Country. O'Connor sounds like the NZ equivalent of some of the Fenians who tried to build anti-colonial armies in the Americas. I'd love to investigate him in detail. https://books.google.co.nz/books?id=mr9HBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA128&lpg=PA128&dq=vincent+o%27malley+fenians+and+maori&source=bl&ots=fdJgY71WK2&sig=H2DkPzz2HwUcz2NSUrsIIoNXWyw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=oYdvVdjbLaKOmwXzvICIDA&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=vincent%20o'malley%20fenians%20and%20maori&f=false

Looks like Philip Catton has looked at some of these issues himself:

http://www.academia.edu/4234718/Philosophy_Matauranga_Maori_and_the_Meaning_of_Biculturalism

This comment has been removed by the author.

I met Phillip Catton at a philosophy teachers conference in Christchurch some time ago and he was a mighty nice chap. I also heard him present his paper on Matauranga Maori that anon mentions above. From what I remember of the talk, he concluded that Matauranga Maori and Western knowledge systems were completely incommensurable in epistemological terms. It was a fine and detailed argument he gave for this view. I then showed Phillip and other philosophy teachers my film Tongan Ark, which is a possible empirical refutation of his view - the paradoxical Tongan philosopher Futa Helu seemed to have no trouble reconciling the radical empiricism he learned from western philosophy with what he might have called an indigenous 'Tongan realism'. Phillip mentioned that he would forward me some criticisms of the film but I never heard from again. I'd still very much value hearing those ideas now Phillip (after you've answered Scott of course)!

Fascinating, Paul - I was just saying during a debate on twitter today that Catton should study Futa Helu!

https://twitter.com/SikotiHamiltonR/with_replies

I think he sounds like a kind of middle of the road liberal, US Democrat kind of thinker. I think you are wrong to lump Hume in there as an atheist. He is very important in the area of epistemology.

But what you have written here is good.

It is fairly well known these contradictions re the enlightenment and in fact one can go back to Shakespeare (of say 'The Tempest' which is NOT re politics as such but has a "cannibal", that is Caliban, as a prisoner of Prospero) where he has created one of the strangest and most fascinating works ever. Nothing is clear. Part of this might be ascribed to his reading of Montaigne who wrote on Cannibals. Montaigne strongly critiqued the Spanish who slaughtered Indians in the North and Middle Americas (on what he himself said were absurd reasons such as that they ate spiders, and were heathens and so on, that is, he would not have become an "Enlightenment Man" but was certainly a subtle thinker as, this, as well as all the essays (he invented the form) are contradictory in nature. They are complex, like Shakespeare's great plays. You are never sure in most of Shakespeare's plays what is true etc The Enlightenment thinkers did indeed bring new and good ideas. But while this ideal of debate sounds good. It isn't the reality. Philip Catton is right to defend his daughter and to oppose uncritical debate but a little naive to expect a non ad hominem response.

Your taking things towards the heart of things shows up the dangers of the Englightenment thinking, and indeed of much human thinking. It shows, as Paul tried to show via his film, that it doesn't NECCESSARILY require this great Harold Bloomian hieratic tradition stepping up to Democracy. Bloom is good, in fact he is great on The Tempest...and other writings.

But in NZ and Tonga even before European settlers came, Maori had certain ways of living and ways of living that didn't need any European Enlightenment. Of course many of the movements that have arisen such as those by Maori mentioned here came with the 'conflict' between Maori and the settlers (who did more than the British army to dispossess the Maori of their land etc). Judith Binney writes about Te Kooti. We admire him not for any theoretical 'goodness' or even 'democracy'. Who put the 'moc' in democracy? Browning was a great writer, and quite a subtle thinker, but he was part of the British Empire. He was influenced by these ideas (negative and positive).

It does seem that Catton thinks that we have no history of the Enlightenment and or discussion and hence we have Key and the rather dubious fellow he was interviewed by. Actually I thought he was a bit gutless. He seemed almost cowed and even shook Sean Plunket's hand. I would have not been too keen on talking with a mongrel like that, regardless of whether my daughter was right or wrong.

I think he has bourgeois-liberal view and ignores NZ history as well as, as you point out working class struggles. I was also influenced by my time at the Railway Workshops when the Communist Ray Gogh lent me a copy of 'Rape of Vietnam' That he did by simply asking me if I was interested in reading about the subject. That book, and it's subject, the barbarous war of that "enlightened nation", the United States, changed my life, and I have never trusted smarmy liberals ever since.

Comment and reference from Viv Kent:

On reading your article, Cerian Scott Hamilton, I reached to my bookshelf and found my copy of Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze's 'Race and the Enlightenment'. An ... ummm ... enlightening (and depressing) collection of writings on exactly this, drawn from thinkers such as Hume, Blumenbach, Jefferson, Cuvier, and Hegel. For example, Kant (1775): 'This fellow was quite black ... a clear proof that what he said was stupid.'

Such a commentary does sound stupid. There are some good commentators on philosophy but in addition, there is Said and the postmodernists and others to balance them.

Hegel's ideas were used by Marx but probably he influenced developments leading to Nazism also. But the ideas he had are interesting.

To assert that Kant was stupid is stupid, and the reason given is, of course, even more stupid!

Perhaps Martin Rumsby might enter this discussion: https://www.academia.edu/12819468/Indigeneity. ... Gosh that Kant quote is outrageous -- I am shocked, though at the same time I am wondering if the translation might do him a disservice-- perhaps the original was :: "this guy was quite affiliated with the "uncivilised" perpetrators and therefore ignorant of the situation in Germany" or some such (wondering what the original doc was) ... not that I would wish to set myself up as a defender of all these Enlightenment jokers who obviously deserve to have their fingers cut off, be tarred and feathered if not quartered, and their disgusting books burned. :)

PS: a little light relief, perhaps? http://william.direen.online.fr/media/Onaevia-WilliamDireen.pdf

'not that I would wish to set myself up as a defender of all these Enlightenment jokers who obviously deserve to have their fingers cut off, be tarred and feathered if not quartered, and their disgusting books burned. :)'

If I'm prepared to put up with Kerry Bolton's books, then I can handle Kant, Bill!

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.co.nz/2015/03/why-we-shouldnt-censor-books-that-we.html

I think that a one-sided dismissal of the Enlightenment would be as bad as the paean that Philip Catton seems to offer. I think that the Englightenment's fundamental problem is not tied up with an individual knowledge-claim, like, say, Kant's apparent claim that blacks are inferior to Europeans, but with an aspect of its thinkers' method.

As Hans-Georg Gadamer said, the thinkers of the Enlightenment were prejudiced about prejudice. They thought that everyone else was hopelessly prejudiced, and considered themselves to be labouring in the light of the newly risen son of reason. The reality, Gadamer argued, is that prejudice is part of the inheritance of every human being. We all look at the world through a set of assumptions made by our culture and our biography. These assumptions can both aid and encumber us. If we forget that we carry assumptions, then we are inclined to hubris. Of course, Gadamer's argument against the Enlightenment could also be applied to certain other intellectual movements. It could be aimed against certain varieties of Marxism, for example.

This blogger puts it well:

Gadamer finds the Enlightenment’s rejection of authority and tradition an impossible and pointless path to trod. According to Gadamer, though many key Enlightenment thinkers reject tradition, claiming it an impediment to the progress of true Enlightenment (e.g., Kant’s essay, “What is Enlightenment?”) and riddled with unjustified prejudices, Gadamer turns their critique back on them and shows that they in fact hold rather dogmatically to a “prejudice against prejudice.” As Gadamer explains, the Enlightenment has so stressed the negative aspect of the word, “prejudice”, that its positive meaning, “pre-judgment” (Vor-urteil) has been lost. One can in fact (and here Gadamer appropriates insights from Aristotle) by way of proper upbringing, customs and embracing one’s tradition, hold true “prejudices” and biases. Thus, for Gadamer, just because one cannot justify (or as Aristotle might say, give the “why”) of one’s beliefs, it does not follow necessarily that these beliefs are wrong, false or misguided. Because of his positive view of tradition, many contemporary thinkers (Derrida, Caputo) have labeled Gadamer a “dogmatist.” On this point, it seems that some postmoderns have not thrown off the prejudices of modernity either.

On a more positive note, Charles Taylor in his essay, “Gadamer and the Human Sciences,” highlights Gadamer’s rejection of key Enlightenment notions, particularly the desire to make knowledge conform to the image of science or what Taylor calls, “scientific knowledge of the object.” In contrast to this model, Gadamer argues for “coming to an understanding” through a dialogic encounter where the modus operandi is question and answer (here Gadamer draws explicitly from Plato). Gadamer’s model is characterized by the following three features: (1) bilater-ality, (2) party-dependence, and (3) an openness to goal-revision. Regarding (1) and (2) the text or Other is not a silent “object” to be mastered; rather, it “talks” back and can put the interpreter into question, thus challenging her “prejudices” and horizon and allowing for potential self-transformation. Regarding (3), because one’s prejudices and biases can be altered (i.e., if one is open) by a dialogic encounter with the text (Gadamer views texts as a kind of dialogue partner), one must be willing to revision his or her objectives.

- See more at: http://percaritatem.com/2009/11/29/part-i-an-introduction-to-hans-georg-gadamer/#sthash.ldVhS8Lx.dpuf

Hi Richard,

this would have been a fascinating event:

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10453151

I wonder how many veterans of the workshops are amongst the volunteers running miniature train parks at Mangere and in your native Panmure? The track at Panmure is really outstanding: I go there with the kids...

Nzers claiming that Maori who were fighting against nz were nzers fighting for nz. Maori anti-colonial history isnt your history, your history is destroying those movements claiming them as yours is just more colonialism. Don't even know why I bother with the nz left, whatever.

You don't have to bother with the left if you don't want to, anon, but you should bother with the nineteenth century. Maori themselves often used the term Niu Tereni and for many decades during the nineteenth century it was understood to refer to their society, not to Pakeha society. The present use of New Zealand to describe both Pakeha and Maori societies is a fin de siecle innovation. I don't see how there's anything wrong, then, with me describing Wiremu Tamihana as a New Zealander.

Unless we recognise what the words New Zealand and New Zealander meant for much of the nineteenth century, then we run the risk of misunderstanding historical documents, most notably the Treaty of Waitangi. Don Brash and his co-thinkers have claimed that the Treaty cannot be considered to contain any notions of particular rights for Maori, because its references to the people of 'New Zealand' are references to Pakeha as well as Maori. As scholars have pointed out, though, in 1840 the term 'New Zealanders' always referred to Maori.

There's more than just a whimsical reason, then, for using New Zealand and New Zealander in a post like this...

Re the Railway event. I probably might have known a couple of them but most I knew are dead or very old, although, Bill Lee, who started the PYM and lead a successful movement there to get apprenticeships reduced, was, together with his brother, Barry, at my schools (Tamaki College) etc in the early 60s.

He was a fitter. Tuwhare was a boiler maker. It is a very noisy job. I had my name down for gas cutting but didn't get onto it. It is the first stage before welding. When the boiler makers start working the noise is almost unbearable. It was a great place to work though. It was then that we all listened to the report of the moon landing, which, as it happened caused the whole place to shut down, but Charlie Baker, an ex (Scottish-born) British Army seargent who became a communist or Marxist while in the army, and read all kinds of things such as (in fact on that train the old fellow mentions), I recall (as I used to meet up with him on the train) he was reading 'The Arms of Krupps', and a large book about Jean-Paul Sartre and his "existential Marxism" which puzzled me at the time but it was interesting. He could talk for hours about history and events and his politics. He was rather dogmatic but an interesting character in GI-Panmure. He was (I think, not sure his real role) the "chief theoretician" for the CP at the time. Ray Gogh, who I saw on marches and on the Spring Bok tour protests, commented of him when I said he knew a lot but didn't protest, that he was "all talk and no do'! A bit unfair.

But his protest that historic day was to continue working as he had read about the My Lai massacre (which was only the tip of the ice-berg of the atrocities committed by so-called allied soldiers in Vietnam and Korea and elsewhere). It affected him a lot as he had been ordered to undertake "search and destroy missions" in India. This meant he could interprete the order, which explains a lot (why Medina, William Calley and others for example more or less got away with such war crimes without much happening to them except a short jail term or two).

It is not a new policy.

But that was part of my education, and talking about a lot of things in lunch times, and clowning around, and listening to the the older men talk of their experiences.

Yes, probably quite a few got into making those trains. I've seen that track. I must take my grandsons when they are a bit older on a fine day. That's if my daughter drops them on a Sunday.

Re Kant etc you have to be wary of which Kant or even which Rousseau or which Hume etc you are talking about. They are part of the "march of events" so to speak. I think it's Gadamer I saw hoeing into Plato of the Republic, but people, in reading all of Plato, can learn a lot, and can react against or with him. Just as the ideas of the pre-Socratics can clash or connect with those of the later philosophers to Aristotle and later all the way to Derrida etc I don't think that the line from them to Derrida is irrelevant. You can put the logical positivists up against such as Nietzsche, Heidegger, and the more recent "continental philosophers" and they are an ongoing dialogue. Rarely in agreement. So the unthinking worship of 'The Age of Reason' or 'The Enlightenment' can be as dangerous as addiction to PMism. Nothing wrong with a bit of irrationalism or relativism and nihilism to leaven or mix into the bread of you rationalism or other isms!

But the point was the sidelining of what the Maori thinkers contributed (and indeed Polynesian culture in general (and other such cultures), and that is something I saw as I read what Catton said.

I think you're right not to throw the Enlightenment baby out with the bathwater Scott. The intense argument between Gadamer and Habermas is informative. Habermas saw Gadamer as creating an idealist theory that didn't account for the possibility of ideological deception in actual political praxis. This is where the 'ontological egalitarianism' of the Enlightenment method with it's emphasis on the material conditions finds its importance (sounds Marxian ay!? - and very much inherited from the Greek scientific revolution!) The 'fusion of horizons' is just another seductive idea that distracts us from what's happening on the ground!

PPS: Martin Rumsby again: https://www.academia.edu/12819468/Native

Thanks Bos.

De Nature Indonesia

De Nature Indonesia asli

De Nature asli

De Nature

De Nature Indonesia Asli

Obat Sipilis Tradisional

Gujarat Postal Circle Hall Ticket 2016

kmat hall ticket 2016

Bihar Anudeshak Hall Ticket 2016

RSMSSB Livestock Assistant Hall Ticket 2016

Thanks Great article shared.

Login

Login

Login

Login

Login

Learn everything about T20 World Cup Schedule 2020 including the venues, time table, dates and much more to stay updated.

Post a Comment

<< Home