The lost land of aute

Over at EyeContact the Panmure psychogeographer Richard Taylor has made a typically thorough response to my essay about Nikau Hindin, the young artist who is trying to reanimate the ancient Maori art of tapa making.

When I told friends about Nikau Hindin's recent exhibition at Manurewa's Nathan Homestead gallery a lot of them thought I was hoaxing. They were sure that Maori had never made tapa. Even when I showed them some promotional material for the show, I suspect that they thought it might be some sort of 'Forgotten Silver'-style joke. The notion of Maori tapa confuses many of our categories, it seems.

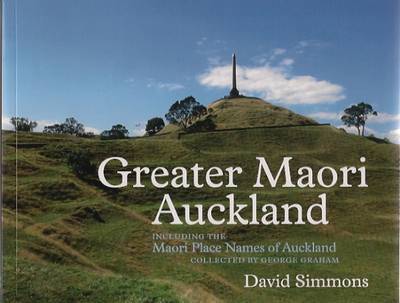

Coincidentally, I was reading David Simmons' fascinating book Greater Maori Auckland this week, and I found a chapter about the flat and sandy islands that once existed off Awhitu and in the Kaipara harbour. These 'lost lands' were slowly eaten by wind and water, and now exist only in a melancholy photograph and some oral traditions. I'd known about the lost land of Paorae, thanks to this article by James Cowan, but had never heard of the sunken Kaipara island of Taporapora.

Simmons says that Taporapora, which is today no more than a mangrove bank off a tiny bach village at the end of a peninsula in the central Kaipara, was once the home of a whare wananga and of a famous plantation of aute. It was interesting to learn this story, because several aute beaters have been found close to Taporapora, in the mud-choked mouths of the rivers that feed the Kaipara harbour. Oral tradition and archaeology seem, then, to support one another.

Simmons says that Taporapora, which is today no more than a mangrove bank off a tiny bach village at the end of a peninsula in the central Kaipara, was once the home of a whare wananga and of a famous plantation of aute. It was interesting to learn this story, because several aute beaters have been found close to Taporapora, in the mud-choked mouths of the rivers that feed the Kaipara harbour. Oral tradition and archaeology seem, then, to support one another.

I wonder whether we couldn't also bring palaeoclimatology to the table, and ask whether a microclimate helpful to the raising of tropical plants like aute might have existed at Taporapora half a millennium or so ago.

Microclimates certainly exist in the Kaipara region today: olives and other Mediterranean crops are grown on the Tinopai peninsula, which extends into the harbour from the north, and is known for its warm and dry weather.

David Simmons reports that different groups settled Taporapora at different times. The second group to settle on the island brought aute, and presumably wielded aute beaters. In my essay on Nikau Hindin I report linguist Roy Harlow's belief that different Eastern Polynesian peoples settled Aotearoa at different times, before coalescing and becoming the ancestors of Maori. Harlow detects a trace of Mangaian in the dialects of regions like the Kaipara.

Perhaps a fragment of tropical Polynesian society established itself and persisted in a stable state for some time, on the atoll-like island of Taporapora, centuries before the emergence of what we know today as Maori culture?

I wish our archaeologists had a submarine, so that they could look at the ancient lands of Taporapora and Paorae.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

Microclimates certainly exist in the Kaipara region today: olives and other Mediterranean crops are grown on the Tinopai peninsula, which extends into the harbour from the north, and is known for its warm and dry weather.

David Simmons reports that different groups settled Taporapora at different times. The second group to settle on the island brought aute, and presumably wielded aute beaters. In my essay on Nikau Hindin I report linguist Roy Harlow's belief that different Eastern Polynesian peoples settled Aotearoa at different times, before coalescing and becoming the ancestors of Maori. Harlow detects a trace of Mangaian in the dialects of regions like the Kaipara.

Perhaps a fragment of tropical Polynesian society established itself and persisted in a stable state for some time, on the atoll-like island of Taporapora, centuries before the emergence of what we know today as Maori culture?

I wish our archaeologists had a submarine, so that they could look at the ancient lands of Taporapora and Paorae.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

3 Comments:

This is very good. I know Brett used to live up that way. Cowan writes very well (I once had a book of his factual stories). He was quite enlightened and prepared to talk with Maori. I believe he knew Maori.

Derrida et al undermine these ideas of say spoken language being purer than written (which Plato argues for, he thinks that it weakens the memory etc I think in the Theatatus, but Derrida questions all these notions of purity (including that we ever had a "pure" body, an initial, totally innocent state (so of course he, respectfully, deconstructs [questions, opens up] the writings of Rousseau who is nevertheless an important philosopher in the canon per se, and he realised that...): so these tales told would in fact be MORE RELIABLE or AS RELIABLE if written down. Both modes, in fact any language mode is subject to error etc, but that doesn't matter as things can be passed on either way....

In any case the memory of the kumara lands becomes a fictionalised truth or a truthalised fiction...something like that subject to the same 'erosion' the sea gradually brings about (this is the genius of the kaumatua who told the story of it, he realised it was of indeterminate time and even place: much is known, but much will remain unknown, everything decays as in W. G. Sebalds novel set in the East of England where things are crumbling away into the sea, where memory is doubtful (this arises inter alia in a short novel called 'The Bookshop' by Penelope Fitzgerald): and no submarines, no investigation will uncover it. It is good to leave some things unknown, untouched. Knowledge can mean death.

Meanwhile Panmure remains as complex as any place on this earth from the micro to the macrocosmic level. I am repairing my house as I prepare it for painting at the moment.Much occurs here that time will also obliterate like the kumara lands.

The tapa or aute were / are made, it seems. It can now become a new tradition. It doesn't require precedence or permission.

Nice post and looking forward to read more.

Would make sense. The very old traditions of the area are wonderful. One I learnt tells of the last moa found near Riverhead. There were also taro grown in the south Kaipara. Marine archaeology is pretty rare in most places, and particularly NZ it seems, though a colleague of mine trained in it.

Post a Comment

<< Home