The trench and the pyramid: Ian Barton's Pokeno

[This is some more of the material I'm bringing together in the book Ghost South Road, which will be illustrated by Paul Janman and Ian Powell. I'm fascinated by the different ways in which Ian Barton and Brett Graham remember the redoubts of the Waikato War, and plan to put the two men in the same chapter.]

1.

Pokeno was almost surrounded. On the northern, southern, and eastern edges of the village herds of bulldozers, dump trucks and graders were turning low hills into flat stretches of orange soil, and thousands of houses were rising as implacably as the gorse and woolly nightshade that used to torment local farmers. On the southern side of the Razorback Hills, a couple of kilometres from the Waikato River, Auckland was establishing its southernmost suburb.

With their beige brickwork, double garages, and grey wooden fences, the houses around Pokeno could have belonged to the outer suburbs of Sydney or Los Angeles or any other overgrown First World City. While the houses that swarm on the outskirts of Pokeno were the work of commercial developers, the new building in the middle of the village was raised by a charitable organisation, the Queen's Redoubt Trust. It was made from timber and iron rather than brick and tiles, and its high ceiling and thick walls were homages to the military architecture of the nineteenth century. The Queen's Redoubt Visitors Centre was surrounded by a deep and muddy trench, rather than a fence.

I met Ian Barton, the chairman of the Queen's Redoubt Trust, in the Pokeno Country Cafe, beside the Great South Road. It had been raining for three days. Barton sat down in his raincoat, ordered a coffee, pulled a handkerchief from his pocket, and carefully wiped the rectangular lenses of his glasses dry. He had bushy white eyebrows and receding white hair and his smile was slightly lopsided.

Barton was born in 1937, and grew up in a valley of the Hunua Ranges, where veterans of the World Wars ran cattle and sheep amidst black kauri stumps. After a career as a forester he retired to Pukekohe, where he was elected to the town council. He joined the Trust while he was a councillor, and quickly became fascinated by the history of Queen's Redoubt.

'I grew up close to Pokeno' Barton told me, 'but I never knew about Queen's Redoubt. After I joined the Trust, I was taken to the site. I expected to see something impressive - high walls, signs of a battle. There was nothing, nothing at all, just a paddock and a modern house. But I became fascinated with the site. I rebuilt it in my head, as I researched it. And then I wanted to rebuild it for real.'

The Queen's Redoubt Trust was founded at the beginning of 1999. In 2002, when Auckland's property boom was a rumour, the Trust used grants from the Lotteries Commission and Auckland Savings Bank to buy five acres of land that included the site of the redoubt and a three bedroom house. The house was rented out, to give the Trust an income.

Trust members started digging ditches in 2003, and raised two sheds to give them shelter from the sun or the rain when they were taking smoko breaks. By 2006 the Trust had launched a stylish and very detailed website, and in 2007 it began holding educational Open Days amidst the earthworks it had reconstructed. Work on the Visitors Centre began after the Trust won three more grants in 2012 and 2013.

In a report to the 2015 Annual General Meeting of the Queen's Redoubt Trust, Neville Ritchie, an archaeologist and the manager of the Queen's Redoubt site, counted the hours of volunteer labour that members of the Trust had performed at the site. In 2014 Ian Barton had given four hundred and fifty-four hours, or more than seven working weeks, to the organisation. The rest of the members, together, had contributed two hundred hours.

When he wasn't digging and wheelbarrowing at Pokeno, Barton was excavating paper. As well as ransacking the reference libraries of New Zealand, Barton had travelled to Britain and searched the National Archives at Kew for maps and notebooks and classified reports that British officers and administrators had brought home from New Zealand.

'I need to learn everything I can about the Waikato War' Barton said. 'I've made two trips to Britain. In Kew I opened a leather pouch and discovered a cache of hand drawn documents. They were the maps made for General Cameron, as he advanced south into the Waikato.' Barton handed me a folder filled with the Trust's newsletters and brochures, and with his own unpublished research notes. It was as thick as an encyclopedia.

The cafe had filled with cyclists in psychedelic skinsuits and a group of middle-aged Indian men brushing raindrops off their ties. Were these inhabitants, I wondered, of the new Pokeno?

Pokeno's developers like to invoke the village's rural history. Pokeno Village Estate is raising hundreds of homes on twelve parcels of land to the north and east of the Great South Road. The development's website calls Pokeno 'an urban village in a rural setting' with a 'strong local character'. By buying a brick and tile house on a tiny plot of dirt in Pokeno Village Estate, one can 'build upon' Pokeno's pioneering tradition, and 'thrive off this fertile land'.

In an article published in September 2015, though, Waikato Times journalist Florence Kerr described the disorientation that some of Pokeno's long-time residents feel, as they find their village 'in the fast lane' of development. Kerr remarked on the incongruity of Pokeno's new, brick and tile developments, beside the village's older timber houses. She talked with Anne Manukau, a lifelong resident her feared that her village was becoming a 'mini city', and complained of harassment from real estate agents. For Kerr, the difference between the old and new Pokeno was 'severe'.

2.

Yet Pokeno has a history of transformations. At the beginning of the 1860s Auckland was the seat of New Zealand's government and the home of its most ambitious businessmen. But the government's authority evaporated on the southern fringes of Auckland, and its property speculators and bankers lacked land and debtors. The Maori King Tawhiao had named the Mangatawhiri, a creek that flowed into the Waikato a couple of kilometres south of modern-day Pokeno, as the northern border of his realm, and had forbidden his subjects to sell land to Pakeha.

In 1862, at the request of Governor George Grey and the government in Auckland, military engineers pushed the Great South Road to the border of Tawhiao's kingdom. Mileposts and pubs were raised along the road. In early 1862 General Duncan Cameron, the commander of British forces in New Zealand, travelled down the half-finished road and stopped at Pokino, a Maori village close to the site of today's Pokeno. A flour mill had been built at the village, and chiefs from the Waikato had been bringing wheat across the Mangatawhiri to grind at the mill and sell in Auckland. Cameron decided to build his largest fortress close to Pokino.

By the middle of 1863 six thousand men were living in wooden barracks halls and tents behind Queen's Redoubt's square-shaped trench. The fort had its own reading room, hospital, brass band, and hall. On the evening of the 11th of July 1863, a few of the redoubt's soldiers crossed the trench and raided Pokino. The village had already been deserted by Maori; the soldiers burned its whare. No one had authorised their raid.

The morning after the attack on Pokino General Cameron marched hundreds of his troops out of Queen's Redoubt to the Mangatawhiri, where a fleet of whaleboats waited. The boats had been dragged down the Great South Road, over the Bombay Ranges and the Razorback Hills. Cameron's men paddled across the Mangatawhiri, and by dusk were building a new fort on the south side of the creek. After the conquest and confiscation of the Waikato Pokeno was settled by some of the war's surviving soldiers, as well as by land-hungry Aucklanders and assisted immigrants.

Queen's Redoubt was closed in 1867. Its buildings were sold off and removed, and in the 1920s its earthworks were erased by a local farmer experimenting with a new-fangled tractor. 'He filled the ditches in with earth' Ian Barton said. 'The site was made invisible.' He chuckled, shrugged his shoulders.

As the motor car became more popular Pokeno acquired a service station and a garage, and become a place to pause on journeys to and from Auckland. Highway Two, which runs across the Hauraki plains toward the mountains and beaches of Coromandel, intersects with the Great South Road just beyond Pokeno, and holidaymakers would stop to fill their cars with petrol and their stomachs with ice cream. Geoff Murphy shot one of the scenes of Goodbye Pork Pie in Pokeno. The heroes of his film accidentally steal a tank of petrol from the service station, and thus begin their careers as outlaws.

In 1992 Auckland southern motorway was extended beyond the Bombay Ranges; Pokeno was bypassed. The village cast about for a new role; in 2000 it made the peculiar decision to rename itself temporarily jenniferann.com, after the website of a local business owner and philanthropist. In 2010 the Waikato District Council eased up rules for development around the village, and announced that Pokeno was 'poised for growth'. Auckland's property boom did the rest.

3.

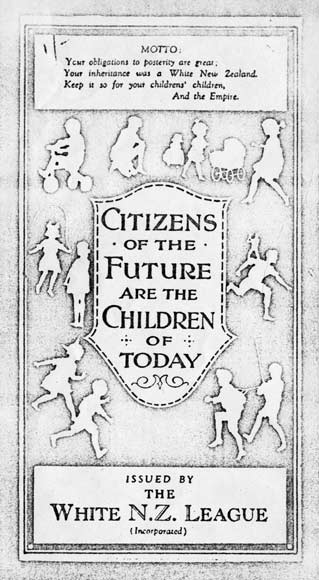

Pokeno sits in the middle of a district with a reputation for racism. In the 1920s and '30s nearby Pukekohe was the birthplace and stronghold of the White New Zealand League. The League was alarmed by the Chinese and Indian market gardeners who were settling in the Franklin District and employing and intermarrying with Maori. It campaigned for a ban on immigration by non-whites, and denounced miscegenation as an offence against nature.

In the 1940s and '50s pubs in Mercer, Pukekohe, and Papakura were repeatedly criticised for denying service to Maori, and the cinema at Pukekohe was accused of segregating its patrons along racial lines. Today Pukekohe is home to the Franklin E Local, a magazine that insists that Europeans rather Maori were the first settlers of New Zealand, and that warns of nefarious conspiracies by Maori radicals, the United Nations, and Muslims. The E Local has a circulation of twenty thousand.

'It is hard to interest local Pakeha in the war' Ian Barton admitted. 'Pakeha have a guilty conscience. Many of the older Pakeha who live here, the long-time residents - they have ancestors who invaded the Waikato. It's personal. And then there's the material in Franklin E Local. Lost civilisations. Fantasies. But it is because people need to learn the real history that the Trust exists.'

'What about relations with Maori?' I wondered.

'Well, it hasn't been easy there, either. There has been some suspicion of the Trust, of our project.'

When the Trust began building on the redoubt, it decided to call its visitor centre The Barracks. Members of Ngati Tamaoho, a subtribe of Tainui which whakapapas back to the obliterated village of Pokino, were upset by the suggestion.

'They accused us of wanting to glorify the invasion and the war' Barton explained. 'To them, the redoubt is still a symbol of aggression. They throught we were going to gather in our barracks, just as the imperial troops had done, and continue the work of colonialism. We hadn't intended to glorify the redoubt, of course. We dropped the name immediately. We consulted, and chose the neutral Queen's Redoubt Visitors Centre instead. Relations were difficult for a while, but now we have two Ngati Tamaoho leaders, George Wheatley and Hero Potini, on our board. We're very happy to have them.'

One of the damp businessmen was paying for a round of chai lattes with an ASB platinum card. I suddenly wanted to ask Ian about Karl Marx, about The Communist Manifesto, that supposed classic of radicalism which begins with a paean to the destructive powers of capitalism. Writing in the late 1840s, the young Marx enthused about the invasion of Asian societies by European armies and capital, and looked forward to the end of the 'idiocy and backwardness' or rural life, as capitalism turned peasants into workers and poured tarseal over fields. Modernisation is a step towards enlightenment, because it destroys old ways of life and thought.

I'd always disliked the youthful Marx's celebration of anabolic capitalism; I didn't see how the Opium Wars and the British Raj were anything but idiotic and backward. Now, though, I wondered whether Marx's glee about capitalism's destructiveness might be justified by twenty-first century Pokeno. The rural rednecks who scaremongered about Asian immigration and constructed conspiracy theories about pre-Maori civilisations were being inundated by a suburban Auckland population that was unlikely to share their obsessions. And the new Asian inhabitants of Pokeno seemed about to make the xenophobes' nightmare of ethnic diversity come true.

Perhaps the transformation of Pokeno and Franklin should be celebrated? Were the developers tearing up the hillsides outside town unconscious revolutionaries, destroying the idiocy and backwardness of rural life?

But perhaps the revolution was not as unstoppable as I imagined. It is not hard to find a parallel between the craving for property in twenty-first century Auckland and the land hunger that motivated the conquest of the Waikato. In the 1860s Auckland property speculators fomented the war against King Tawhiao, encouraged thousands of soldier-settlers and assisted immigrants to take over land confiscated from Maori, and then bought this land for almost nothing when its owners were unable to make a living from running a few cows or chickens on their plots.

Today property speculation is sending a new army of home buyers south of the Bombay Ranges and the Razorback Hills. The lower Waikato has again become a promised land for Aucklanders. But will the new settlers be able to pay their mortgages, or will they, too, have to walk away from their homes in a few years?

4.

I asked Ian Barton what he thought about Pokeno's transformation.

'I think everyone at the Trust is hopeful' he replied. 'Hopeful that some of the new residents will be volunteers. We need them in our organisation, and they will be very welcome. A few of them must be retired, must be looking for things to do.'

'This has traditionally been a very conservative area' I said. 'You admit yourself that many locals are reluctant to think about the war, and when they do think about it they tend to take a very defensive line. Do you think the new arrivals might be free of the old inhibitions?'

'Well, perhaps' Ian said. 'But someone may not be interested in history at all and still join our Trust. They might like gardening and enjoy the challenge of our earthworking. They might simply enjoy the camaraderie.'

At the table next to ours a couple of middle-aged men in swandris and gumboots had been talking in neutral voices about visits from Fonterra's milk inspectors. Now, though, one of them scowled, and gestured at a huge orange digger and a grader being carried down Pokeno's main street on a semi-trailer truck. The load was so heavy that the cafe's windows vibrated slightly as it went by. I imagined the trucks and diggers and graders as tanks, patrolling a captured town.

'That rain seems to have stopped' Barton said, after the truck had passed. 'Shall we visit the redoubt?'

5.

Rain was falling again by the time we'd walked the couple of hundred metres down the Great South Road to the reconstructed redoubt. Wind was blowing the rain into our faces, but Barton resisted the shelter of the Visitors' Centre, and led me along the edge of the redoubt's trench, showing me the hundreds of sandbags he and his comrades had filled with Pokeno soil. When we reached the southeastern corner of the trench Barton noticed a frail ragwort growing between two sandbags. He kicked at the enemy, and it fell from into the trench's muddy water.

Before I met Ian Barton I had planned to ask him whether his work at Queen's Redoubt was part of some wider programme. Did he believe that, by remembering and understanding the Waikato War, New Zealanders would be better able to deal with the twenty-first century? Did he have strong political sympathies, and did they influence his work for the Trust? Was he a supporter of what Franklin's rednecks like to call the 'Treaty industry' and the 'Maori gravy train'?

But questions like these suddenly seemed redundant, as Barton talked about the depth and width of the redoubt's defensive trench, and the names of the young men who died in the redoubt's hospital, and the time it took for a cartload of soldiers' biscuits to travel from Auckland to Pokeno down the Great South Road in 1863. Blake wrote that 'every minute particular is holy': Barton felt a reverence for the minute particulars of the Waikato War, not for one or another interpretation of them.

The empty Visitors Centre smelt of varnish. 'A few Victorian-era military installations have survived, in this or that part of New Zealand' Barton explained. 'An old blockhouse, a barracks, that sort of thing. Our architect studied these buildings, then created this.' His voice echoed off the high wooden ceiling. 'This large room will be filled with signboards and with exhibits. The backroom, which is smaller, will have a library, and will be a place to meet. In ten years or so we'd like to open a much larger centre. But we have to start somewhere.'

6.

I knew Nigel Prickett when I worked at Auckland's museum. He was slightly stooped, after decades of service in the trenches of the New Zealand Wars. Prickett made the first serious excavation of Queen's Redoubt in 1992, and published a long essay about his discoveries

Near the end of the report on his findings Prickett reproduced a photograph of nineteen fragments of nineteenth century crockery. There was a teacup handle, there were shards from saucers, there were pieces of a chamber pot. Geometric patterns covered much of the crockery; flowers and leaves occasionally grew from the grids and bands of lines.

Prickett's treasures reminded me of the older pottery that archaeologists have coaxed from the sand and mud of tropical Polynesia. Three thousand years ago the Lapita ancestors of Tongans and Samoans made bowls and cups out of orange clay, and covered them with networks of white lines in which half-human faces seem to emerge and recede. The songs and dances of the Lapita people are lost, but we have their pots. If the earth is a book, then pottery is its script.

7.

Ian Barton drove me north, up the Great South Road and across train tracks, toward the Razorback Hills, through the rubble of a housing development. The road was just beginning to steepen when Barton braked. In a field surrounded on three sides by new houses a white pyramid rose beside a cypress tree. A few headstones ran in an erratic line across the grass.

'Do not take the names on this monument too seriously' Barton told me, as we stood beside the pyramid. 'There are people on the list who lie elsewhere, and many others who lie here but are not on the list.'

I asked him about the irregular arrangement of the graves. Why hadn't the soldiers been buried in rows? At other New Zealand Wars cemeteries soldiers were carefully arranged, as though they were about to undergo an inspection. At Pokeno's cemetery, though, military discipline seemed to have broken down.

Barton shook his head. 'The soldiers are lying in rows here, it's just that most of them lack headstones. Only the higher ranking men got stones; the others were given wood. Headboards, with their names and dates scratched on. The boards rotted, and no one replaced them.'

'Nobody looked after this place?'

'By the 1870s this cemetery was already submerged in scrub. Stock were grazing here at other times. There were eventually grumbles from veterans, and in 1899 the government commissioned a memorial.'

The memorial was made by John Bouskill, an Auckland mason who would later raise obelisks in honour of the dead of the First World War. Using the soft white stone of Oamaru, Bouskill shaped a pyramid, and gave it flat faces where the names of buried soldiers could be incised. At the apex of the pyramid he carved a series of rifles, and leaned them against one another.

Bouskill was a self-taught builder and an orthodox Methodist, but his Pokeno pyramid and his later obelisks suggest he had an interest in relics of Egyptian religion. In the nineteenth century the deciphering of hieroglyphs and the excavation of tombs made an ancient civilisation seem suddenly accessible to the West. European and American dandies built pyramids as follies on their estates; sphinxes grew on railway stations and courthouse facades. Some twenty-first century sources, like Te Ara, New Zealand's national encyclopedia, describe Pokeno's memorial as a cairn, but early observers were in no doubt: it was a pyramid.

After the invasion of Tawhiao's Kingdom wounded men began to returning across the Mangatawhiri, to the hospital at Queen's Redoubt. Some of them died of the wounds that musket balls and tomahawks had made, and were buried on the hill at the northern edge of Pokeno. The redoubt's brass band played, and riflemen fired a salute.

Some deaths were ordinary, and therefore mysterious. One night in October 1863 Augustus Selwyn, the Anglican bishop of New Zealand, was holding a service in the redoubt's reading room. The congregation had just finished a hymn when an artilleryman named Edwin Gabbitas slumped in his seat. Gabbitas was carried outside, in the hope that the cold air might revive him. Instead he sighed twice and died. Gabbitas had been a soldier for five years, and had never shown any sign of sickness. He was given a headboard on the hill.

As we walked slowly around the memorial, I asked Ian Barton why Bouskill chose such an unusual shape. Was the pyramid a triumphal gesture, a boast that the British Empire, which has so recently absorbed the land around Pokeno, would endure as long as Egypt? Or was there something melancholy and antiquarian about Bouskill's choice of the pyramid form, an acknowledgement that Britain, like all the great powers of the past, would eventually dwindle in importance?

Ian wiped rain off his forehead and chuckled. 'We don't know that this is a pyramid. It might be a cairn. I have considered it a cairn. Admittedly, the style is unusual. But this was a fragile place, even after the war. The settlement struggled. Sometimes farms failed, bush started to come back. The soldiers turned small farmers, the assisted immigrants who arrived after the war - they were probably not feeling like they'd won anything. It was probably important to have reminders of history, identity. Memorials, chapels. Then again, the cemetery was not well maintained. Even after the placement of this memorial it was allowed to become overgrown.'

I wasn't prepared to give up. 'What about an Egyptian reference? Would you find that completely unlikely, from Bouskill, at the end of the nineteenth century?'

We had stopped circling the pyramid and were gazing at its list of names. Ian coughed gently. 'I don't know about Egypt. I'd have to study that. Egypt, the influence of Egypt - it's another field entirely. Perhaps I'll look at it.'

I felt guilty again, as I imagined Ian Barton reading through volumes of Egyptology, and making a research trip to Giza, on the way home from his next expedition to Britain's archives. The man surely had enough work to do, without me giving him more.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]

4 Comments:

Interesting indeed. A lot going on at Pokeno. I remember when the GSR was longer and the motorway shorter. I saw all those earthworks. Auckland is expanding and swallowing up a huge area of good land.

Marx had some strange ideas. His influence has been big but I think it has all been shown to be a dream. Nothing much has come of his manifestos. People are now in a very different mode. The Opium War is written about by Agnes Smedley who was an American Socialist writer who went to China. The epic by her I read in about 1970 was The Great March about Chu Teh and opium addict, who cured himself of his addiction, and was in fact who was a 'warlord' and converted his whole mass of 'gangsters' to the communist cause (as did many many others trying to rid China or the corrupt old regime, the Japanese and colonialism) and he became known or confused by the peasants as legendary warrior called Chu Mao.

Marx was very much a theoretician - although he took part in action in the 1848 revolutions - and from the Middle Class. In fact he had connections with the aristocracy. But he had some important ideas.

Your Great South Road epic will show that history is not just the goodies versus the baddies as we used to play as kids. It is always complex, always changing. It is good that people such as those doing the Redoubt or investigating battle sites and monuments can elighten. Interesting that what we might think of as "bad" (more immigrants etc) is in fact the force whereby humans have made real progress. So if there are Indians, India is a place colonised hundreds of years ago by the Moguls etc and later the British. Now those colonised are haunting the red neck lands but maybe some of those rather problematic Pukekohians will learn something from the mix of cultures. And it was that mix of ideas or resources by the mixing of cultures that has always contributed to development. Whether it is all "progress" is another issue. I doubt it. But it is change. But it is interesting to realise our own history also, for European and Maori and others.

I hadn't realized the Jackels of Real Estate were busy in Pokeno. The Government needs to stop speculators. They wont as they have mates with big money investing. Also auctions should be stopped. Auctions drive up prices.

But as you intimate there are complex "pay offs" in these things. I think though, that the younger Marx sounded rather unpleasant (I know the rather wooden theory he had of the way the class revolution needed to happen, and it didn't ever really work out the way he imagined it).

Interesting 'human details' brought in. Interesting.

Thanks Richard. I was remembering your expedition down the motorway/GSR to see the stars with Victor!

Yes. We went to Pukekohe and stopped by what turned out to be an Ostrich farm. We waited for the light to go down and I took some photographs, and we saw some people on the farm looking towards us. The police came a bit later wanting to know what we were doing and were a bit dubious that we were there to look at stars!! But Vic believes there are aliens for sure and possibly thought he might see a space ship from somewhere...We then went closer to where your parents' farm is and it was a bit better there.

Re stars it is certainly not so good in Auckland. It wasn't so bad in the 60s when I used to use a refractor telescope my grandfather made and read books about astronomy but I didn't see as much as I would like. But it was interesting.

Yes, one feels that that area is right wing although we are not maybe talking about the US South but I suppose the police acted on a complaint which they have to do. We may have been 'up to no good'.

Kami sekeluarga tak lupa mengucapkan puji syukur kepada ALLAH SWT, dan terima kasih banyak kepada aki bromo atas bantuan angka ritualnya yang aki berikan 4D dan 3D ternyata itu benar-benar tembus 100% aki... dan alhamdulillah sekarang saya bisa melunasi semua hutang-hutang saya yang ada sama TETANGGA dan juga BANK BRI dan bukan hanya itu aki insya Allah saya akan buka usaha sendiri demi mencukupi kebutuhan keluarga saya sehari-hari itu semua berkat bantuan aki, sekali lagi makasih banyak yaa aki.. BAGI SAUDARA/SAUDARI YANG PUNYA PERMASALAHAN EKONOMI ATAU TERLILIT HUTANG PIUTANG SILAHKAN HUBUNGI AKI BROMO DI: =085 - 288 - 958 - 758= insya allah anda bisa seperti saya menang togel ( 455 JUTA ), dan anda tidak usah ragu lagi akan adanya penipuan atau hal semacamnya sebab saya sudah buktikan sendiri, Saya Jamin aki bromo tidak akan mengecewakan. SEMOGA SUKSES AMIN...!!!

Post a Comment

<< Home