Origin Myths

Over at his blog Richard Taylor has published one of his meditations, asking again and again Who were the first people? The question involves metaphysics as well as history, because it takes us back not only to our origins as a species but to our most fundamental knowledge-claims: back to the Garden of Eden, or to the savannah of Africa. I remember irritating my parents and teachers by asking the question repeatedly when I was growing up.

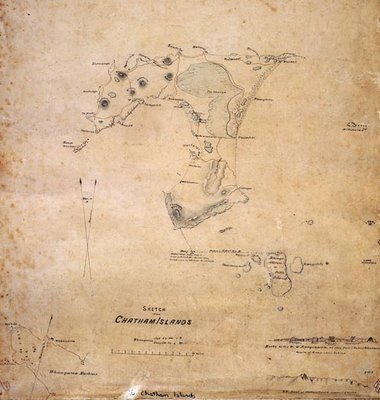

Over at his blog Richard Taylor has published one of his meditations, asking again and again Who were the first people? The question involves metaphysics as well as history, because it takes us back not only to our origins as a species but to our most fundamental knowledge-claims: back to the Garden of Eden, or to the savannah of Africa. I remember irritating my parents and teachers by asking the question repeatedly when I was growing up. For New Zealanders the question has, or ought to have, a special pungence: the first people in these islands were also, in a very real sense, the last people. By the time the Polynesians were spreading out across the vast reaches of the Pacific Ocean the rest of the world had been populated, and New Zealand was probably amongst the last places the Polynesians reached - it was certainly the last sizeable place settled by humans. Our first people were the last indigenous people. The last part of New Zealand to be settled - the final discovery of the Polynesians - was the Chatham Islands, a couple of thousand kilometres east of Christchurch, in a cold and wild part of the South Pacific. There is not so much as a rock between the Chathams and South America. Birds which overfly those islands die.

Richard discusses the claim of nineteenth century pseudo-anthropologists that the Moriori, the indigenous people of the Chathams, were the remnants of a pre-Maori people who had once occupied the whole of the North and South Islands before being driven to a remote redoubt. In reality, the Moriori were a group of Maori who were isolated on the Chathams and over hundreds of years developed a distinctive culture and language. The myth of the pre-Maori Moriori lives on outside of academia, as a convenient excuse for the Pakeha dispossession of Maori. 'We only did to you what you did to the Morioris, mate...'

Many Pakeha believe they know the name of the last Moriori. Tommy Solomon, a Chatham Island farmer of prodigous proportions, died in 1933, and was commemorated as the 'last of his race'. Pakeha obsessed with eugenics and the notion of racial purity had recognised in Solomon the last 'pure blood' Moriori. They were apparently unfamilair with the Polynesian notion of identity, which has no place for concepts like 'half-caste'.

A few Pakeha dissenters pointed to reports of a Moriori who lived in the Hokianga region of the North Island until the 1940s. Kendrick Smithyman believed that he set eyes on this man, and wrote a poem about him which when published caused an outcry from the Solomon family, who had become accountably jealous of their melancholy status:

taken for a slave when a boy, taken

again in some other raiding, passed

from band to band, from place to place

until he washed up on the River.

Today the Moriori are very much alive but, as Smithyman wrote, 'The fact is, and the myth is, and they endure together'.

2 Comments:

Thanks Maps - "the first people were the last people" yes - my idea of oriigns asyoupointoutis inclusive of all aspects - the Big Bang - creation myths - where person came from and so on -

Itis an ontological existential and scientific as well as a political and personal and historical question...perhaps ultimaely unanswerable. But great question.

Spelling! Again -

Thanks Maps - "the first people were the last people" yes - my idea of origins - as you point out - is inclusive of all aspects - the Big Bang - creation myths - where a person came from and so on -

It is an ontological existential and scientific as well as a political and personal and historical question...perhaps ultimately unanswerable. But great question.

Post a Comment

<< Home