Smoke in their eyes

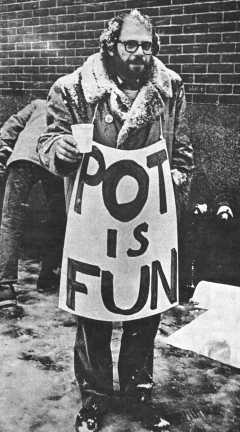

Nine years old in 2006, J Day has become a respectable Kiwi festival event, something to be gawked at and photographed by tourists and given thirty seconds' good-natured coverage at the tail end of the TV news.

Nine years old in 2006, J Day has become a respectable Kiwi festival event, something to be gawked at and photographed by tourists and given thirty seconds' good-natured coverage at the tail end of the TV news. Every year, opponents of the criminalisation of marijuana gather in the country's main cities, usually in some green and pleasant park, to smoke a few joints, to relax, and to listen to some music. A few token police usually attend these laidback protests, but they rarely bother to ruin the fun by making petty arrests. Often they look as relaxed as the protesters. Policing J Day sure beats breaking up a picket line or defending the US embassy from anti-war protesters, let alone trying to bring order to the terraces at Eden Park during a one day cricket match. This year's J Day statement from the National Organisation for the Reform of Marijuana Laws was as mellow and optimistic as the mood of the protesters who got stoned in Albert Park. 'Your presence can and will end prohibition', NORML's blurb assured its readers.

Call me a party-pooping pessmist if you like, but I find it rather difficult to see any reason for NORML's ebullience. In fact, I think it would be fair to say that the decriminalisation let alone legalisation of marijuana looks further away in 2006 than at any time in the last two decades. NORML has always sought to use its lobbying skills and its protests to exert influence on parliament to scrap existing dope laws, but today the vast majority of MPs are hostile to its arguments. The Greens are the only parliamentary party which endorses law reform, yet they are less keen on championing the idea than they were in the past, fearful as they are of antagonising 'mainstream voters' by looking like 'fringe hippies'.

NORML once entertained hopes of winning the Act Party to a pro-reform position, and even displayed a sympathetic quote from Rodney Hide on its website, but at last year's election Act and Hide hastily backtracked on the issue. The major parties may hold one or two dope law dissenters, but their leaderships show no sign of being prepared to moderate their blanket opposition to law reform.

Even worse, the current hysteria over the use of P and the public crucifixion of Marc Ellis and his mates for using ecstasy suggests a new mood of fear and intolerance towards illegal drugs. Faced with anti-social behaviour and high suicide rates in depressed areas of the country, both politicians and headline writers prefer to reach for a scapegoat, rather than talk about the impact of globalisation, deindustrialisation and chronically high unemployment and underemployment in places like Manurewa, Minginui, and Opotiki. The recent hikoi against P was a sad example of ordinary people from these places kicking the same scapegoat.

It seems, then, that we can look forward to thousands more young people acquiring a criminal record, and sometimes even going to jail, because they like to smoke a joint rather than sink a Steinlager or Lion Red. We can look forward to more problem drug users being locked up for long periods instead of getting the counselling and medical help they need. We can expect more junkies to OD on heroin under bridges. Why is drug reform still such a remote prospect in New Zealand? Why have decades of NORML activity yielded so little?

To answer these questions we need to look at a country where the movement for the reform of drug laws has been successful. NORML is fond of drawing attention to the dope cafes of Amsterdam, but the Netherlands has not gone very far in reforming drug laws. The country has liberalised laws concerning marijuana, but it still hands down stiff penalties for the use of other drugs, from LSD to ecstasy to heroin. In 2004, though, one country radically reformed its drug laws, decriminalising the possession of virtually every drug which is banned in the Netherlands and other Western countries. Article 383 of Venezeula's criminal code is intended to definitively end the criminalisation of ordinary people and the unnecessary suffering of drug addicts, by eliminating the senseless fines and prison terms that coventional drug law demands and by making money available for drug education and rehabilitation instead. Venezuela's proximity to the Andean heartlands of coca production has ensured that a significant proportion of its population has developed drug problems. The new law offers these people hope, instead of fear. Commenting on the legislation shortly before it was passed into law by Venezuela's National Assembly, penologist Jose Luis Tamayo noted that it would correct a serious injustice:

"Today those who traffic drugs in large quantities (for example, a ton of cocaine) are punished with the same sentence as those who traffic in small quantities (for example, 10 grams of cocaine)...In this manner, the greater or lesser the quantity of the drug detected in each case would be punished in a proportional manner [under the new law, anyone caught with a small amount of a drug like cocaine for personal use avoids crminal prosecution]"

NORML has stayed silent about Venezuela's dramatic moves against drug prohibition. Visitors to the group's website, for instance, will search in vain for information about President Chavez's historic law. What is the reason for this reticence? If NORML can hail the tinkering with drug laws that took place in the Netherlands, how can it ignore the much more significant changes seen in Venezuela?

It seems to me that the success of Venezuela in tackling its drug prohibition laws shows up what is wrong with the political strategy that NORML uses here in New Zealand. NORML and its electoral spin-off the Aotearoa Legalise Cannibas Party have always gone out of their way to stress their status as single issue, almost apolitical concerns. NORML and ALCP leaders have often proudly proclaimed that they attract members from across the political spectrum, from the left to the far right. NORML's rather pathetic attempts to court Rodney Hide reflect its view that drug prohibition is an issue that transcends the left-right divide; a right-winger like Hide might be as useful in bringing prohibition to an end as anybody on the left.

But anti-drug laws do not exist in splendid isolation: they have a point of origin, a history, and a purpose. Marijuana was not always demonised and banned: in certain eras it was regarded as a useful and respectable herb. George Washington grew and smoked it; so did the Catholic nuns who founded the famous Jerusalem settlement north of Wanganui. The campaign against marijuana and other 'bad' drugs began in the early twentieth century, in the United States. By the 1950s, anti-drug laws had become firmly established in the Land of the Free, and the US government had begun to use them as an instrument of foreign policy. In 1989, the US used its 'war on drugs' as an excuse to invade Panama. Today its uses the same excuse to pour money, helicopters, and 'military advisers' into Colombia to fight left-wing guerrillas that threaten the puppet Uribe government. The US has demonised the newly-elected Bolivian President Evo Morales as a 'narco-terrorist', when what it really fears is the possibility that Morales' militantly anti-Bush supporters might touch the property of US multinationals operating in Bolivia.

Over decades, the US was able to force prohibition on most of the world, using a mixture of coercion and persuasion. Today, New Zealand is a signatory to numerous treaties which effectively institutionalise an international 'war on drugs'. New Zealand's commitment to this endless war is intertwined with the commitment it makes in other treaties to the free movement of capital and to US foreign policy.

To oppose drug prohibition means taking on not just a few cops in Albert Park but the might of US imperialism. It means breaking with the neo-liberal economic policies and neo-conservative diplomatic and military policies that the US pushes on its allies and the countries it dominates. The political elite of the Netherlands stopped its drug law reform programme as soon as it realised this.

The Clark gvernment knows that any bold moves it made to end drug prohibition would quickly bring the wrath of the US down upon it. At a time when it is desperate to negotiate a free trade deal and overcome the animus generated by its nuclear free policy, Labour has no appetite for a confrontation with the US over drugs. Brash's National Party has even less appetite for such a confrontation.

When we understand what challenging prohibition really means, we can understand why Venezuela's government has been able to end prohibition. Venezuela is in the midst of a 'Bolivarian' revolution: millions of its people have been involved in efforts to reorganise their society so that it is economically and militarily independent of the US. By establishing worker-controlled factories and enterprises, reforming the ownership of land and setting up collective farms, reorganising the army and police so that they act for rather than against the people, and refusing to go along with the US's push for 'free' trade and co-operation with its War of Terror, the Venezuelan masses and their government have begun to break out of the system of imperialism.

The US tried to overthrow the Venezuelan government in a CIA-sponsored coup, but the masses rushed to the government's defence and foiled Bush's plans. The US has angrily denounced Venezuela's drug law reforms, and tried to destabilise the country by bringing the 'war on narcoterrorism' it is supposedly fighting in neighbouring Colombia into Apure, a Venezuelan state that borders Colombia. But Bush has been unable to get his way. Having stood up successfully to Bush, the Venezuelan masses are now in a position where they have much greater scope to decide their own destiny. They have created the space in which measures like the reform of drug prohibition is possible.

As we have seen, NORML's strategy of persuading New Zealand's political elite to see the light and reform drug law has yielded minimal gains, despite decades of effort. NORML is blowing smoke in its supporters' eyes by telling them that by smoking a few joints in Albert Park they can reverse drug prohibition. NORML needs to recognise that challenging the war on drugs means challenging US imperialism and the US's economic hegemony over New Zealand. It goes with out saying that the likes of Rodney Hide can never be allies in such a challenge. Drug law reform is not an issue that transcends left and right - it is an issue which belongs to the anti-imperialist left. Like the fight against 'free' trade and the fight against the War of Terror, the fight against unjust drug laws can only be won by the left.

2 Comments:

um, where exactly did we say that? You're putting words in our mouths. Here's our press release and webpage:

http://www.norml.org.nz/article593.html

http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO0604/S00108.htm

We don't kid ourselves that merely smoking a joint will end rohibition. NZ has the highest joint-smoking rate in the world so if that were true the law would have changed years ago. J Day is a day of protest and civil disobedience. Supporters can make their feelings known, become informed and get active. It's a day where people who would otherwise be secretive and paranoid realise they are not alone, can become empowered and hopefully take further action.

I agree that Venezuela does have perhaps one of the best laws around, but because it is not English speaking nor Western it's domestic policies will have little influence here in New Zealand. Sad but true.

You have made some good points and sparked some internal discussion of our strategies, which is always good.

I disagree with your assessment, however, of how "little" has been acheieved here, and with how much influence the US has on our policies. For a start, cannabis arrests have dropped by more than 10% in each of the past 4 years. In part this is a result of NORML's work educating people about their civil rights, and in part it shows the public taste for arresting drug users is waning. We came *very* close to changing the law in 2001-3, and anyone who followed that inquiry knows that in the end politics overrode the evidence but that is hardly NORML's fault.

I also take issue with your assertion that Marc Ellis was "crucified"; if anything the opposite occured. He is still on TV, still has his endorsements and sponsorships and is still the lovable rogue.

You also overstated the influence of the P hikoi, which was poorly attended and hardly represented any sort of ground swell against drug users.

I don't think the US has had *any* influence over Labour's decision to go into coalition with Peter Dunne. This is purely domestic politics and unfortunately cannabis laws are not as important to Clark et al as being in power. They can get votes from the Greens whenever they want - a consequence of the Greens painting themselves as more left than Labour. It was more important to Labour to pick up the centrist votes of NZ First and United Future, thereby shifting the coalition government further to the centre/right with the aim of picking up the votes that had migrated to National so specatacularly last election.

I also have to disagree that ending prohibition is exclusively the domain of the left. Right-wingers tend to suppport individual rights, the freedom to choose, freedom of beliefs, right to privacy etc. These values are consistant with drug law reform and we would be naive and simplistic to ignore this side of the political spectrum. Having said that, it is true that most of our support has come from the left, the disadvantaged and the marginalised. I think this has more to with the repressing effect of drug criminalisation, in that people who work or have families or reputations they care about will be less likely to out themselves by coming to J Day or being involved at all. Those with less to lose, such as the young (and rebellious), students, etc, will be more open to getting involved. This creates a difficult situation, whereby the power elite excuse themselves from the debate, leaving it up to hippies, lefties and students, who tend to have the least influence in society. This is the real reason so "little" has been acheived.

Regards,

Chris Fowlie

president,

National Organisation for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) NZ Inc.

Amen to the last paragraph by Chris Fowlie.

Only when the "powerful' get off their arse can something happen, not just the "dope smokers".

Only when the media stop bashing drugs and report proper facts instead of jumbling P and Alcohol with Cannabis in every newspaper article can the madness end.

Post a Comment

<< Home